This content originally appeared on The Real News Network and was authored by The Real News Network.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on The Real News Network and was authored by The Real News Network.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

As sky-high rents and a housing shortage become major issues in the 2024 presidential election, the U.S. Justice Department has sued software company RealPage, alleging its algorithm enabled landlords nationwide to collude in raising rents on tenants. The DOJ says the price-fixing scheme has impacted millions of renters across the United States. ProPublica reporter Heather Vogell, whose investigation first exposed RealPage, says as much as 70% of big apartment buildings in some neighborhoods are owned by property managers using RealPage, with landlords seeing the software “as a way to have a rising tide that lifts all boats.” We also speak with tenant rights organizer Tara Raghuveer, who says RealPage is guilty of “some of the grossest, most extractive business practices” documented in recent years, but the firm is hardly alone. “For so much of the market which is a catastrophic failure, landlords’ business model is predicated on tenants’ instability,” says Raghuveer.

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on ProPublica and was authored by ProPublica.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on ProPublica and was authored by ProPublica.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

ProPublica is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up for Dispatches, a newsletter that spotlights wrongdoing around the country, to receive our stories in your inbox every week.

Ten months after Georgia officials said they would take steps to ensure that counties were correctly handling massive numbers of challenges to voter registrations, neither the secretary of state’s office nor the State Election Board has done so.

In July 2023, ProPublica reported that election officials in multiple Georgia counties were handling citizens’ challenges to voter registrations in different ways, with some potentially violating the National Voter Registration Act.

Instead of fixing the problem, the Republican-controlled Georgia legislature passed SB 189 at the end of March. The bill’s authors claim that it will help prevent voting fraud, while voting rights advocates warn that it could make the issue worse. Gov. Brian Kemp signed it into law on Monday.

“I see this as being pro-America, pro-accuracy, pro-transparency and pro-election integrity,” state Rep. John LaHood said of the bill, which he worked to help pass. “I don’t see it being” about voter suppression “whatsoever.”

When it takes effect in July, SB 189 will make it easier for Georgia residents to use questionable evidence when challenging fellow residents’ voter registrations. Voting rights activists also claim that the law could lead county officials to believe they can approve bulk challenges closer to election dates.

“It’s bad policy and bad law, and will open the floodgates to bad challenges,” said Caitlin May, a voting rights attorney for the American Civil Liberties Union of Georgia, which has threatened to sue over what it says is the law’s potential to violate the NVRA.

ProPublica previously reported on how just six right-wing advocates challenged the voter registrations of 89,000 Georgians following the 2021 passage of a controversial law that enabled residents to file unlimited voter challenges. We also revealed that county election officials may have been systematically approving challenges too close to election dates, which would violate the NVRA.

The Georgia secretary of state’s office said at the time that it was “thankful” for information provided by ProPublica, that it had been working on “uniform standards for voter challenges” and that it had “asked the state election board to provide rules” to help election officials handle the challenges. And the chair of the State Election Board told ProPublica last year that though the board hadn’t yet offered rules due to the demands of the 2022 election, “now that the election is over, we intend to do that.”

With the new law soon to be in effect, the State Election Board is determining its next steps. “We’re going to probably have to try and provide some instruction telling” election officials how to respond to SB 189, said John Fervier, who was appointed chair in January after the former chair stepped down. “I don’t know if that will come from the State Election Board or from the secretary of state’s office. But we’re one day past the signing of the legislation, so it’s still too early for me to comment on what kind of instruction will go out at this point.”

Mike Hassinger, a public information officer for the secretary of state’s office, said in a statement that it falls to the State Election Board to review laws and come up with rules. “Once the board moves forward with that process we are more than happy to extend help to rule making,” Hassinger said.

Conservative organizations have been vocal about their plans to file numerous challenges to voter registrations this year, providing training and other resources to help Georgians do so. Activists and Georgia Republican Party leadership publicly celebrated the passage of SB 189, with the GOP chair telling the Atlanta Journal-Constitution that this year’s legislative session was “a home run for those of us concerned about election integrity.”

But what has not gotten as much attention is how individuals who were involved in producing massive numbers of voter challenges managed to shape SB 189.

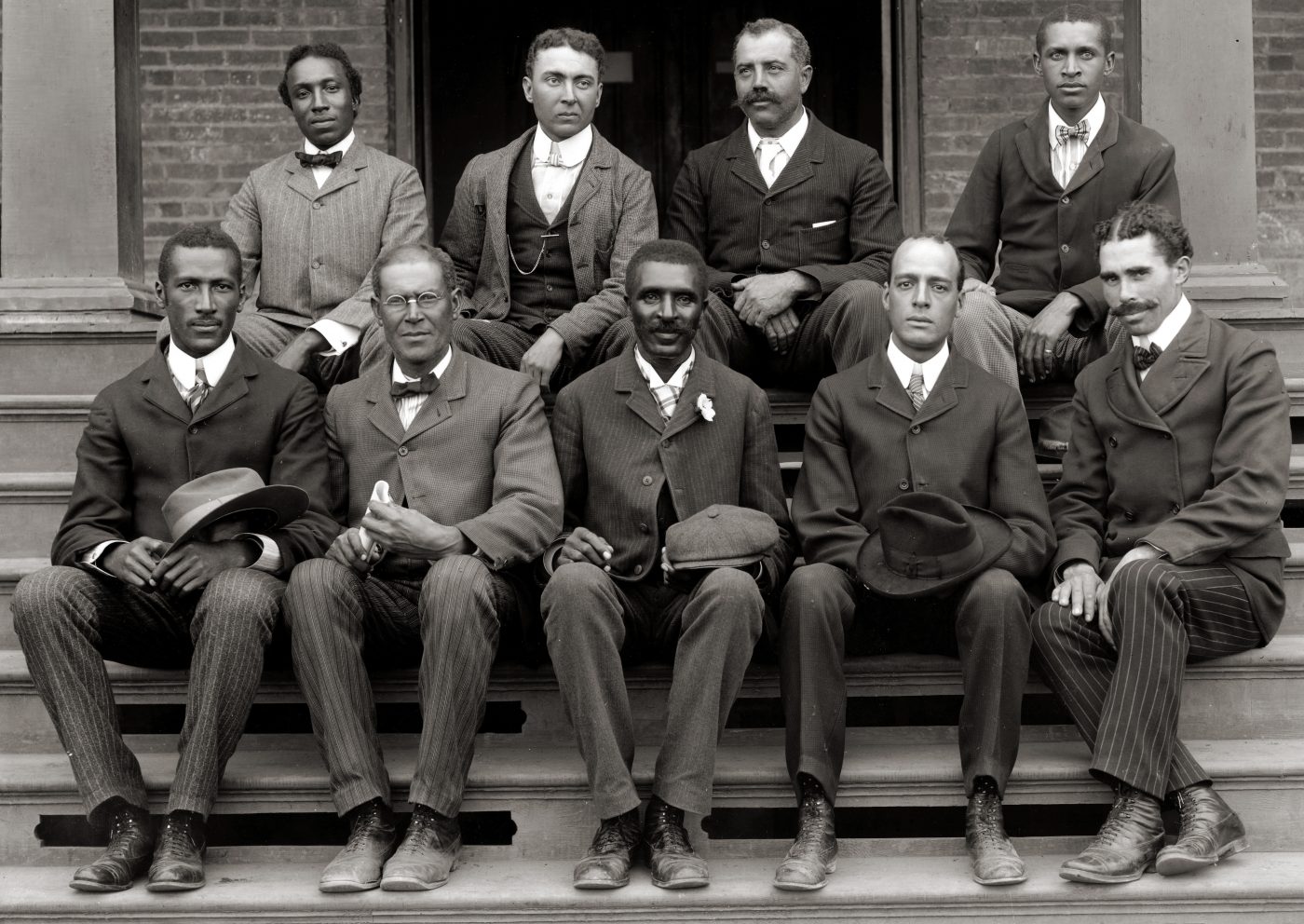

Jason Frazier, who in 2023 was a Republican nominee to the Fulton County election board, challenged the registrations of nearly 10,000 people in Fulton County, part of the Democratic stronghold of Atlanta. (Cheney Orr for ProPublica)Courtney Kramer, the former executive director of True the Vote, a conservative organization that announced it was filing over 360,000 challenges in Georgia after the 2020 presidential election, played an instrumental role in getting the bill passed. She was the co-chair of the Election Confidence Task Force, a committee of the Georgia Republican Party that provided sample language to legislators crafting SB 189. An internal party email reviewed by ProPublica thanked Kramer for her dedication in helping bring “us to the final stages of pushing essential election integrity reform through the legislature.” Kramer said in a statement that “my goal was to restore confidence in Georgia’s elections process” and to “make it easy to vote and hard to cheat.”

Jason Frazier, who ProPublica previously found was one of the state’s six most prolific challengers, served on the Election Confidence Task Force. Frazier did not respond to requests for comment.

In late July, William Duffey, who was then the chair of Georgia’s State Election Board, was working on a paper to update county election officials on how to handle voter challenges. But when the board met in August 2023, a large crowd of right-wing activists packed the room, and dozens of people castigated the board for defending the legitimacy of the 2020 election. One mocked a multicultural invocation with which Duffey had started the meeting, declaring, “The only thing you left out was satanism!” A right-wing news outlet accused “the not so honorable Judge Duffey” of hiding “dirt” on the corruption of the 2020 election.

Less than a month later, Duffey stepped down. He denied that activists had driven him out, telling ProPublica that pressure from such activists “comes with the job.” But, he explained, the volunteer position had been taking “70% of my waking hours,” and “I wanted to get back to things for which I had scoped out my retirement.”

According to two sources knowledgeable about the board’s workings, who asked for anonymity to discuss confidential board matters, Duffey had been the primary force behind updating the rules about voter challenges, and without him, the effort stalled. One source also said that the board had realized that Republican legislators planned to rewrite voter-challenge laws, and members wanted to see what they would do.

In January 2024, Republican legislators began working on those bills. The one that succeeded, SB 189, introduces two especially important changes that would help challengers, according to voting rights activists.

First, it says a dataset kept by the U.S. Postal Service to track address changes provides sufficient grounds for election officials to approve challenges, if that data is backed up by secondary evidence from governmental sources. Researchers have found the National Change of Address dataset to be unreliable in establishing a person’s residence, as there are many reasons a person could be listed as living outside of Georgia but could still legally vote there. ProPublica found in 2023 that counties frequently dismissed challenges because of that unreliability. And voting rights activists claim that the secondary sources SB 189 specifies include swaths of unreliable data.

“My worry is” that the bill “will cause a higher success rate for the challenges,” said Anne Gray Herring, a policy analyst for nonprofit watchdog group Common Cause Georgia.

The new bill also states that starting 45 days before an election, county election boards cannot make a determination on a challenge. Advocates have expressed concerns that counties will interpret the law to mean that they can approve mass, or systematic, challenges up until 45 days before an election. The NVRA prohibits systematic removal of voters within 90 days of an election, and election boards commonly dismissed challenges that likely constituted systematic removal within the 90-day window, ProPublica previously found.

When True the Vote was challenging voters in the aftermath of the 2020 election, a judge issued a restraining order against the challenges for violating the 90-day window.

Whether SB 189 violates the NVRA could be settled in court, according to voting rights advocates and officials. On Tuesday, after SB 189 was signed, Gabriel Sterling, the chief operating officer for the Georgia secretary of state, disputed on social media that the new law would make voter challenges easier. But months earlier, he said that imprecision in the voter challenges process could lead to legal problems.

“When you do loose data matching, you get a lot of false positives,” Sterling said, testifying about voter list maintenance before the Senate committee that would pass a precursor to SB 189. “And when you get a lot of false positives and then move on them inside the NVRA environment, that’s when you get sued.”

This content originally appeared on ProPublica and was authored by by Doug Bock Clark.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Welcome to the Gaslit Nation State of the Union Super Special! This episode has everything! Suge Knight dissing Diddy at the 1995 Source Awards! World War II era journalist Dorothy Thompson’s warnings about Katie Britt! A dictator loving pope! George W. Bush’s pandora’s box of evil! A smirking Russian oligarch on the Oscars’ stage! You’ve never heard a state of our union analysis, and where we must go from here, quite like this.

Terrell Starr of the essential Black Diplomats Podcast and Substack joins Andrea to roast Katie Britt and her antiChrist diamond cross and what it says about the GOP’s Christofascist war against our democracy. The conversation includes the history of white women like Britt enforcing the genocide of slavery, and Andrea and Terrell accidently calling Steve McQueen’s masterpiece film Seven Years a Slave! (Yes, we now recall it’s 12 Years a Slave!) Andrea shares the story of how she once went undercover as a self-hating Republican woman at a GOP fundraiser and almost got caught by being the only woman who dared to eat food!

Our bonus this week, for subscribers at the Truth-teller level and higher, exposes the Kremlin Caucus and their financial backers. That episode will feature Olga Lautman and Monique Camarra of the Kremlin File podcast. To our supporters at the Democracy Defender level and higher, submit your questions for our upcoming Q&A! We always love hearing from you! Thank you to everyone who supports the show – we could not make Gaslit Nation without you!

Fight for your mind! To get inspired to make art and bring your projects across the finish line, join us for the Gaslit Nation LIVE Make Art Workshop on April 11 at 7pm EST – be sure to be subscribed at the Truth-teller level or higher to get your ticket to the event!

Join the conversation with a community of listeners at Patreon.com/Gaslit and get bonus shows, all episodes ad free, submit questions to our regular Q&As, get exclusive invites to live events, and more!

Check out our new merch! Get your “F*ck Putin” t-shirt or mug today! https://www.teepublic.com/t-shirt/57796740-f-ck-putin?store_id=3129329

Thank you to the sponsor of this week’s episode! Andrea got to try Factor, and now her listeners can, too, with this special deal! Head to FACTORMEALS.com/gaslit50 and use code “gaslit50” to get 50% off. That’s code “gaslit50” at FACTORMEALS.com/gaslit50 to get 50% off!

Listen to and support the Black Diplomats Podcast: https://www.blackdiplomats.net/

Listen to and support the Black Diplomats Substack: https://terrellstarr.substack.com/about

Watch 20 Days in Mariupol (full documentary) | Academy Award® Winner https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gvAyykRvPBo

Why Haiti Collapsed: Demanding Reparations,and Ending Up in Exile

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/05/20/world/americas/haiti-aristide-reparations-france.html

President Biden on hot mic says he needs a ‘come to Jesus’ meeting with Netanyahu

Journalist catches Sen. Katie Britt in an ‘out and out lie’ in her State of Union response

https://www.rawstory.com/katie-britt-out-and-out-lie/

Pope Francis: questions remain over his role during Argentina’s dictatorship

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/mar/14/pope-francis-argentina-military-junta

With Haiti on the Brink of Collapse, a Reckoning for US Policy on Haiti

Biden’s State of the Union: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nq9vmRd67lc

Clip: Jonathan Glazer acceptance speech https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sMc1khOqEFE

Clip: Suge Knight at The Source Awards https://www.youtube.com/watch?si=QHg1JImJqIZ7xkB5&v=mv2OMXngkEs&feature=youtu.be

We didn’t end up including this clip in this week’s episode, but it’s worth watching: Katie Britt Appears on ‘Inside the Actors Studio’ in Edited Version of Her Scorned GOP Response https://www.thewrap.com/katie-britt-inside-the-actors-studio-video/

Pope Francis: questions remain over his role during Argentina’s dictatorship

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/mar/14/pope-francis-argentina-military-junta#:~:text=The%20Catholic%20church%20and%20Pope,evidence%20is%20sketchy%20and%20contested.

This content originally appeared on Gaslit Nation and was authored by Andrea Chalupa.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

“According to respected polls,” Ira Shapiro writes at The Hill, “public approval of the Supreme Court has dropped precipitously to the lowest level in the 50 years that it has been measured.” And not, he cautions, not just to recent revelations concerning the less than ethical (those are my polite words for “bribe-accepting”) behavior on More

The post Term Limits Wouldn’t Fix the Supreme Court appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

This content originally appeared on CounterPunch.org and was authored by Thomas Knapp.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

How to solve the territorial disputes in the South China Sea that have flummoxed diplomats for decades and stoked fears of superpower conflict?

Actually, it’s quite simple, according to British scholar Bill Hayton. Just acknowledge that the current occupiers of each feature have the best claim to sovereignty over it.

Hayton, associate fellow in the Asia-Pacific Program at Chatham House, a U.K. think-tank, shared his views in a recent commentary in “Perspective,” a publication of the Singapore-based ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute.

He argues that researchers now “know enough about the history of the South China Sea to resolve the competing territorial claims to the various rocks and reefs.”

The basic facts of the South China Sea disputes are well-known. Six parties – Brunei, China, Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan and Vietnam – have competing territorial claims. China holds the biggest claim, up to 90 percent of the sea, demarcated by a so-called nine-dash line. It says it has historical rights to the area – a position rejected by an international tribunal in 2016 that Beijing has refused to acknowledge. China’s stance has also put it at loggerheads with Western powers, particularly the U.S.

The disputes are not just about claims to the tiny islets and reefs scattered across the South China Sea, but also claims to jurisdiction over maritime zones associated with these features.

Because of that, a seventh country, Indonesia, also has a stake. Although it does not regard itself as a party to the South China Sea dispute, China claims historic rights to parts of the sea overlapping Indonesia’s exclusive economic zone.

Hayton says that of the six formal claimants, all claim at least one islet, and “a few islets are claimed by at least five states.” The rival claims have always been thought to be “too complicated to ever sort out.”

“There are too many rocks and reefs, too many claimants, too much history. Trying to understand and disentangle all the overlapping claims is just impossible, or so people thought,” said Hayton.

“I don’t think that’s true,” he said.

“Territorial issues in the South China Sea only started in the beginning of the 20th century so you don’t have to look at thousands of years of history.”

“The real problem is different claimants have framed their claims to claims to island groups. It would be very hard to try to work out who has the best claim to the whole island group,” Hayton explained.

China and Vietnam, for example, claim the whole of the Paracel and Spratly island chains.

“But once you try to disentangle and desegregate the claims and look at who has the best claim to specific features, then things become a lot easier.”

“No particular country, or state or regime ever controlled the whole of the South China Sea,” he said.

In Hayton’s opinion, breaking down expansive claims to entire island groups into specific claims to named features would open a route to compromise and the resolution of the disputes.

The scholar pointed out that there have been successful precedents in Southeast Asia. Indonesia and Malaysia resolved their dispute over the islands of Ligitan and Sipadan in 2002; as did Malaysia and Singapore over three sets of uninhabited rocks in the Singapore Straits in 2008. In both cases, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) played an important role.

“By ruling out vague claims to sovereignty “from time immemorial” and demanding specific evidence of physical acts of administration, the ICJ also gave the South China Sea claimants a route out of their impasse,” Hayton suggested.

The historical evidence of physical acts of administration on the disputed rocks and reefs suggests, with a few exceptions, that the current occupiers of each feature have the best claim to sovereignty over it, according to the British scholar.

The main exception would be the Paracel Islands where Vietnam occupied about a half until China took over in 1974 after a bloody battle that saw 74 Vietnamese soldiers killed.

“Southeast Asian states have an interest in recognising each other’s de facto occupation of specific features and then presenting a united position to China,” Hayton added.

In the case some countries are unwilling to make use of the ICJ and international law, he suggested that non-governmental organisations could get involved to create a so-called ‘Track Two Tribunal’. Track two typically describes informal or unofficial discussions by people outside of government to help find solutions to complex diplomatic issues.

Hayton said they could “collect rival pieces of evidence, test the claimants’ legal arguments, and present the likely outcomes of any future international court hearing to the claimants and their publics.”

Hayton, however, admitted that the process would not be easy.

“Populations in different countries would be claiming that this is some terrible sell-out but frankly, all of the countries are working on the basis that this is the status quo that they’re going to accept. They need to turn that into a political commitment,” he said.

Hayton’s proposal “would have merit in an ideal world,” said Mark Valencia, a scholar at the Chinese National Institute for South China Sea Studies.

“But unfortunately we do not live in an ideal world and nationalist-infused domestic politics would likely prove a fatal stumbling block to acceptance and implementation of this proposal,” Valencia said, adding that most politicians in Southeast Asian countries “would try to stay as far away as possible.”

The maritime analyst also warned that since China would not accept and adhere to a formal arbitration ruling against it for maritime space, “it is highly unlikely to accept the verdict of an unofficial Track Two Tribunal regarding territory.”

Furthermore, the idea that each claimant keeps what it currently occupies and drops its claims to other features has been proposed before without any takers, he said.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by By RFA Staff.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Need a reason to feel hopeful? We’ve got 50. The 2021 Grist 50 list has arrived, and it’s chock-full of inspiring, brilliant, innovative, and deeply hopeful people — we call them Fixers. These folks know a better world is possible, and they’re putting in the work to make it happen today.

Check out the 2021 list. If you’re feeling inspired, we’d love to hear your nominations for who should be honored next year.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline The 2021 Grist 50 has landed on Mar 23, 2021.

This post was originally published on Grist.

Women around the globe bear the brunt of climate disaster. They are also the ones driving some of the most innovative and successful solutions. This International Women’s Day, Fix hosted an Instagram Live convo between two fabulous femmes and climate communicators: Grist 50 Fixers Maeve Higgins and Thanu Yakupitiyage took to IG to school us on artistic expression, immigration justice, and female leadership and ingenuity in the climate movement.

Maeve is a comic, writer, and co-host of the Mothers of Invention podcast. Thanu is an activist, DJ, and U.S. communications director at 350.org. Their whole conversation is fire — and one we highly recommend watching — but we’ve pulled together a few highlights here for your reading pleasure.

The following excerpts have been edited for length and clarity.

Thanu: For me, DJ-ing is very much about joy. It’s about creating spaces to envision the world we want to see. Ten years ago, when I started in the immigrant rights movement, I often found that it was intense, policy-oriented work. That’s true of a lot of the social justice work that I do. We don’t always think, “OK, what are we fighting for?”

When I DJ, I curate spaces particularly for queer folks, for people of color, for immigrants to connect. It’s about building the world we’re fighting for — I feel an arts practice helps to do that. And I love comedy! I would love to know, for you, what that has to do with climate.

Maeve: That’s so funny, because that is what happened — what you mentioned about joy and levity being a crucial part of what a future would look like. I write about immigration, too, and I’m an immigrant myself. Moving to the U.S. as a white person from Europe really got me curious about other people’s experience, particularly if they’re not white and European. I think a lot of migration stories and climate stories are told like, “Here’s a victim, here’s a person whose life is made up of sadness and tragedy,” and that’s dehumanizing. Humor is a way of returning what’s already in people’s lives. No matter how dark things get, you’re going to giggle at a funeral. Your humanity is going to bubble up in some way.

Thanu: There’s a lot of updating that needs to happen to global immigration policy. When thinking about external migration, we have to think about the role of the United States, of Canada, of Europe, in creating this climate crisis. All of the most polluting industries are from the West. We have to connect climate to imperialism and colonialism, and to the right of communities from the Global South to be able to migrate for their safety and their prosperity.

Maeve: I really connect with that. Talking about this and explaining it to people is valuable work, and I love how you do that. I worry about the message that climate is a threat to national security. I don’t agree with that messaging, because it’s fear-based. What’s a good way to discuss this, and make it known?

Thanu: That framing is super dangerous. I actually think we have to be careful when people say governments should call a climate emergency — I’m like, “Hold up. Let’s actually think about what a national emergency entails. In a national emergency, borders are shut down and communities are oppressed.”

Maeve: That’s exactly how Trump created the “Remain in Mexico” program.

Thanu: Exactly. When it’s put in a national security frame, it’s actually super racist. It stops Black and brown communities from being able to cross borders. I think it’s important not to use the trope of “We have to do something about climate, because otherwise a billion people are going to migrate.” From my perspective, migration is a human right. We need to focus on the industries that have caused the climate crisis, not the vulnerable communities that are moving.

Maeve: We know that the people who are affected first and worst by climate chaos are women. There’s a balance here, where you don’t want to be too prescriptive, especially with language, but you also want to point out that this is really important. On our podcast, Mothers of Invention, we honor the fact that women and femme people are so often the ones coming up with solutions in their communities and outside of their communities. That was kind of an exciting revelation for me, to be honest.

Thanu: That’s exactly right. When we think about the climate crisis, it’s often women who are also holding down the family dynamics, ensuring that their families and communities have food. And when you think about the places most impacted by the climate crisis, whether it’s parts of Africa or South Asia or the Pacific islands, it’s often women and femmes that are trying to figure out how we move from crisis and chaos to resilience and mitigation. And that’s what I love about your podcast, how y’all really center those solutions.

Maeve: There’s another podcast I’ve been listening to called Hot Take — it both enrages and energizes me. One of the hosts is a hardcore investigative journalist, Amy Westervelt, who’s been writing on climate for years and really has got the goods. The other host, Mary Heglar, is an absolutely gorgeous writer. Their podcast is giving me life at the moment. Do you have heroic femmes and women doing work in this space that you’d like to shout out?

Thanu: My friend Céline Semaan from The Slow Factory talks a lot about climate and fashion. And a lot of the climate youth, like Xiye Bastida and Helena Gualinga and Jamie Margolin — there are so many amazing women, femmes, queer folks who are thinking about climate and its intersections. Young people really give me energy. I think they understand the connections here, and also are able to root things in joy.

I don’t do climate work out of fear. I totally recognize that people are fearful. But I think that this year has reinforced to me why we need compassion and kindness and love. This is a rough and tough world. And I’m not fighting because of fear — I’m fighting because we deserve more than this.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Want a fairer, more sustainable world? Let women lead. on Mar 12, 2021.

This post was originally published on Grist.

Women around the globe bear the brunt of climate disaster. They are also the ones driving some of the most innovative and successful solutions. This International Women’s Day, Fix hosted an Instagram Live convo between two fabulous femmes and climate communicators: Grist 50 Fixers Maeve Higgins and Thanu Yakupitiyage took to IG to school us on artistic expression, immigration justice, and female leadership and ingenuity in the climate movement.

Maeve is a comic, writer, and co-host of the Mothers of Invention podcast. Thanu is an activist, DJ, and U.S. communications director at 350.org. Their whole conversation is fire — and one we highly recommend watching — but we’ve pulled together a few highlights here for your reading pleasure.

The following excerpts have been edited for length and clarity.

Thanu: For me, DJ-ing is very much about joy. It’s about creating spaces to envision the world we want to see. Ten years ago, when I started in the immigrant rights movement, I often found that it was intense, policy-oriented work. That’s true of a lot of the social justice work that I do. We don’t always think, “OK, what are we fighting for?”

When I DJ, I curate spaces particularly for queer folks, for people of color, for immigrants to connect. It’s about building the world we’re fighting for — I feel an arts practice helps to do that. And I love comedy! I would love to know, for you, what that has to do with climate.

Maeve: That’s so funny, because that is what happened — what you mentioned about joy and levity being a crucial part of what a future would look like. I write about immigration, too, and I’m an immigrant myself. Moving to the U.S. as a white person from Europe really got me curious about other people’s experience, particularly if they’re not white and European. I think a lot of migration stories and climate stories are told like, “Here’s a victim, here’s a person whose life is made up of sadness and tragedy,” and that’s dehumanizing. Humor is a way of returning what’s already in people’s lives. No matter how dark things get, you’re going to giggle at a funeral. Your humanity is going to bubble up in some way.

Thanu: There’s a lot of updating that needs to happen to global immigration policy. When thinking about external migration, we have to think about the role of the United States, of Canada, of Europe, in creating this climate crisis. All of the most polluting industries are from the West. We have to connect climate to imperialism and colonialism, and to the right of communities from the Global South to be able to migrate for their safety and their prosperity.

Maeve: I really connect with that. Talking about this and explaining it to people is valuable work, and I love how you do that. I worry about the message that climate is a threat to national security. I don’t agree with that messaging, because it’s fear-based. What’s a good way to discuss this, and make it known?

Thanu: That framing is super dangerous. I actually think we have to be careful when people say governments should call a climate emergency — I’m like, “Hold up. Let’s actually think about what a national emergency entails. In a national emergency, borders are shut down and communities are oppressed.”

Maeve: That’s exactly how Trump created the “Remain in Mexico” program.

Thanu: Exactly. When it’s put in a national security frame, it’s actually super racist. It stops Black and brown communities from being able to cross borders. I think it’s important not to use the trope of “We have to do something about climate, because otherwise a billion people are going to migrate.” From my perspective, migration is a human right. We need to focus on the industries that have caused the climate crisis, not the vulnerable communities that are moving.

Maeve: We know that the people who are affected first and worst by climate chaos are women. There’s a balance here, where you don’t want to be too prescriptive, especially with language, but you also want to point out that this is really important. On our podcast, Mothers of Invention, we honor the fact that women and femme people are so often the ones coming up with solutions in their communities and outside of their communities. That was kind of an exciting revelation for me, to be honest.

Thanu: That’s exactly right. When we think about the climate crisis, it’s often women who are also holding down the family dynamics, ensuring that their families and communities have food. And when you think about the places most impacted by the climate crisis, whether it’s parts of Africa or South Asia or the Pacific islands, it’s often women and femmes that are trying to figure out how we move from crisis and chaos to resilience and mitigation. And that’s what I love about your podcast, how y’all really center those solutions.

Maeve: There’s another podcast I’ve been listening to called Hot Take — it both enrages and energizes me. One of the hosts is a hardcore investigative journalist, Amy Westervelt, who’s been writing on climate for years and really has got the goods. The other host, Mary Heglar, is an absolutely gorgeous writer. Their podcast is giving me life at the moment. Do you have heroic femmes and women doing work in this space that you’d like to shout out?

Thanu: My friend Céline Semaan from The Slow Factory talks a lot about climate and fashion. And a lot of the climate youth, like Xiye Bastida and Helena Gualinga and Jamie Margolin — there are so many amazing women, femmes, queer folks who are thinking about climate and its intersections. Young people really give me energy. I think they understand the connections here, and also are able to root things in joy.

I don’t do climate work out of fear. I totally recognize that people are fearful. But I think that this year has reinforced to me why we need compassion and kindness and love. This is a rough and tough world. And I’m not fighting because of fear — I’m fighting because we deserve more than this.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

If you haven’t heard, Fix recently launched a cli-fi writing contest. We are over-the-moon excited about it. Fiction writers have a knack for creating compelling, perception-shifting windows into alternate worlds and making complex issues approachable — and personal. That’s exactly what we hope to do with Imagine 2200: Climate fiction for future ancestors.

Anyone (even you!) can submit a short story that envisions our path to a cleaner, greener, and more equitable world. We’ve enlisted a jaw-droppingly impressive panel of judges to read the best of the submissions and choose the 12 we’ll publish in a digital collection this summer. (Did we mention there’s cash involved? The grand-prize winner will pocket $3,000, with $2,000 and $1,000 going to the second- and third-place winners respectively.)

Sheree Renée Thomas, Adrienne Maree Brown, Morgan Jerkins, and Kiese Laymon know their way around a narrative. Between them, they’ve written more than a dozen books — memoirs, novels, and essay and short story collections that explore race, culture, family, nature, and even time travel. And they’ve earned heaps of awards and distinctions for their outstanding work.

Fix caught up with our illustrious judges to talk about their approaches to climate fiction and other literature, the impact they think it can have, and what they’re hoping to read in Imagine 2200. Their comments have been edited for length and clarity.

Sheree Renée Thomas is a fiction writer, poet, and editor in Memphis. Her works include Nine Bar Blues, Sleeping Under the Tree of Life, and Shotgun Lullabies. Thomas was recently named editor of The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction.

Storytelling is one of the oldest forms of communication. It touches things in us, and it stays in our memories longer, I believe. Art is more vital in these days than ever, as we’re living through a pandemic.

Climate change has been something I have explored in my creative work for a while. It has directly impacted my own family here in Memphis. We used to be able to fish in the Mississippi River, and now that’s not advised. I’m in the middle of a fight to keep an oil pipeline from going through a historic community in South Memphis called Boxtown that was created right after emancipation. People are rallying around that. In the short stories for this contest, I trust that writers are going to look around them and pull up the very real things that are happening in our world right now. Ideas are great, but if you don’t tell me in a way that makes me care about and invest in what happens to the characters, then it’s just so-so.

I think it’s an amazing time for speculative-fiction writers, and it’s so good to see Afrofuturism embraced by a larger community. I’m here for it. So many wonderful writers are adding their voices to the genre. And lots of other creative projects are coming from it — films and animation and graphic novels — and people are using these as case studies for social change in real time. I see it as an open-source code that’s constantly evolving and changing, and that’s the way it should always be.

My advice to writers who are considering submitting: Read your work aloud! It’s an incantation. And it puts the story in a different light. You’ll find some of the missing beats, you’ll find areas you have an opportunity to expand upon. Oh, and send it in on time!

Adrienne Maree Brown is a scholar and activist in Detroit. She is the author of Emergent Strategy and Pleasure Activism, and co-edited the anthology Octavia’s Brood: Science Fiction from Social Justice Movements.

I think it’s difficult in this moment to tell a story about our future that is neither dystopian nor utopian — that’s not some scenario in which we get everyone into a lush green garden and it’s all good, but it’s also not Mad Max Fury Road. Interdependence is going to have to change our trajectory as a species, and I think fiction has to be the place where we try out what that looks like.

I’m very critical of the fiction I write. Every time, I’m like, “I was aiming for Toni Morrison and I landed at The Bachelorette.” But I had good intentions! “The River” is the story that I think comes the closest to cli-fi for me. It is a story about the Detroit River responding to gentrification and climate injustice and fighting back. For me, when I think of climate fiction, when I think of climate justice, I think about partnering with the land. Partnering with the water. Partnering with the air. Partnering with the forces of change that our planet represents — not saving it.

We are heading toward a future in which Black and brown people are the majority in the U.S. — and we are heading toward a future in which climate crisis is guaranteed, based on the behavior we’ve already engaged in. So we are called to be prophets in this moment.

When we did Octavia’s Brood, most of the contributors were non-fiction thinkers, movement thinkers, scholars, academics. And they wrote some of the most prescient, brilliant fiction. So, my advice to writers: Don’t think that it’s outside of the realm of your possibility. We write because we have a critique of the current circumstances. So if you want to change things, here’s the invitation.

Morgan Jerkins is an author and editor in New York City. She wrote This Will Be My Undoing and Wandering in Strange Lands. Her debut novel, Caul Baby, will be released next month.

In this contest, I hope to see stories that focus on Black and brown populations. I hope to see stories that highlight all of the -isms and phobias that have debilitated our society and how they will metastasize with climate change. I also hope people will explore how climate affects us not just on the grand scale, but the granular.

I grew up in New Jersey. This year, I visited my mother for Christmas, and we followed a tradition that she used to follow with her parents: going around the neighborhoods to see the Christmas lights. She noted that it was different this time because there was no snow. That was the first time I thought that not only is the climate changing, perhaps our traditions are changing, too. And tradition, especially familial tradition, is something I have explored in my writing.

I think cli-fi is a flexible term. For me, it means possibility. I think about Octavia Butler’s work — some of the stuff she’s written, we’re living it now. For those of us who read a lot, we understand the power literature wields. Who’s to say writing isn’t a prophecy? Who’s to say that whatever somebody is writing right now might not be the basis for policy proposals in the future?

Ultimately, I hope these stories reveal how our imaginations can help build a better reality. We need to be imaginative about the future and what it could be — not only to serve as a guiding light, but to serve as a balm for these current, difficult times.

Kiese Laymon is a professor of English and creative writing at the University of Mississippi. He is the author of Heavy and How to Slowly Kill Yourself and Others in America. His debut novel, Long Division, will be reissued later this year.

My first novel is about Black kids in Mississippi who go into the woods in 2013, 1985, and 1964. (There’s a time-travel element.) One thing I was exploring was environmental degradation. The woods change from green, to brown, to eventually no longer existing. I wanted to subtextually ask the reader, “What does it mean when these green spaces that rural Black children play in disappear? And why? Does it have anything to do with how close these communities are to power plants and incinerators?” I didn’t make that explicit, but I was trying to show it in the way the kids kept asking why the forest was changing.

I think cli-fi as a genre foregrounds climate’s relationship to people, places, things, and culture. I’m really excited about the elastic way this can be interpreted. In Imagine 2200, I hope people write stories from the points of view of things other than humans. I’m interested in post-human stories — maybe somebody wants to write a story from the POV of the climate itself, or a pine tree, or a crawdad, or a possum. I hope people are as creative as possible, and that they use this opportunity to write a story they might have needed permission to try.

I also hope people who don’t think they mess with sci-fi or cli-fi will be encouraged to apply. Sometimes I’ve had the most success while writing a genre that I didn’t particularly like and wanted to renovate. If you are tired of cli-fi, if you are tired of writing, fam, use this as an opportunity to expand, explore, destroy, and wonderfully, beautifully, tenderly build.

Feeling inspired? Submit your story to Imagine 2200 by April 12! Together, we can fix the world with fiction.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Introducing our star judges for Imagine 2200, Fix’s cli-fi contest on Mar 11, 2021.

This post was originally published on Grist.

Racial justice and climate justice are inseparable. Few would deny this, but that wasn’t always so. For much of its history, the environmental movement has been overwhelmingly white and gave little thought to the impacts pollution and climate change had on people of color and underserved communities. The convergence of the two, which happened no more than a generation ago, came only after the tireless work of activists like Cecil Corbin-Mark.

Corbin-Mark was a towering, didactic man from Harlem who always offered criticism with love. He was equally adept at organizing his neighbors as he was lobbying policymakers. Never afraid to denounce the injustice deeply entrenched in Black and brown communities, much of his life was spent tirelessly battling the colonial mindset so many live under. Growing up in a family actively engaged in the civil rights movement, it’s no surprise that Corbin-Mark became one of the earliest champions of environmental justice, which was a novel, even radical, idea at the time.

For three decades, he demanded justice for underserved and overlooked communities, a campaign he waged until his sudden passing last October at 51. He never stopped getting into what the late civil rights activist Rep. John Lewis would call “good, necessary trouble.”

Even in a year of immeasurable grief for the Black and brown communities grappling with police brutality and a disproportionate share of COVID-19 deaths, Corbin-Mark remained steadfast in the struggle to eliminate toxic pollution, address systemic racism, and implement equitable climate and energy policies. He scored a key victory, too, in helping pass landmark climate legislation that would not only commit his home state of New York to net-zero emissions by 2050, but require at least 35 percent of state energy and climate spending go to pollution-burdened communities.

Corbin-Mark left a legacy that many in the movement, veterans and newcomers alike, will never forget — something three members of the House of Representatives specifically cited when they introduced a resolution honoring the activist for his life’s work. As one of its first employees, Corbin-Mark helped shepherd the growth of WE ACT for Environmental Justice, which was among the earliest organizations to fight environmental racism. Its virtual memorial for Corbin-Mark drew more than 400 people, offering compelling proof of his impact. Many hailed him as a visionary and gifted policy wonk focused on making energy justice the next front in the ongoing campaign for environmental justice.

Among the most lamentable things about his passing is that he didn’t live to see President Biden pass a slew of executive orders centering environmental justice in his climate and economic agendas. Many of Corbin-Mark’s colleagues credit him with helping carve the path that led to such a historic moment. That his life’s work was inextricably tied to the rise of the movement that made it happen is not lost on those who saw him tirelessly defend marginalized communities.

“The time he grew into who he became at WE ACT tracks with how the environmental justice movement has grown,” says 2019 Grist 50 Fixer Kerene Tayloe, director of federal legislative affairs at WE ACT. She tears up recalling Corbin-Mark’s impact on her life. “His ability to understand the importance of policy at the city level, at the state level, and at the federal level was instrumental in changing and preparing us for where we are right now. I just wish he was here to see the day [Biden’s] executive orders came out.”

Corbin-Mark dedicated most of his life to serving communities of color, particularly fighting against the systemic inequities baked into the daily life of his neighborhood. The disparities are evident in even seemingly minute things: Many people in Harlem — mostly low-income people of color — must endure the pernicious summer heat of New York City, while white and wealthier residents just blocks away sit comfortably in their expensive, air-conditioned apartments.

Bringing these connections to what has historically been a white-dominated movement was never an easy endeavor. About a decade after the civil rights movement in the 1960s, the first battle against environmental racism — though the term didn’t exist until years later — began taking shape. State officials in North Carolina decided to dump soil laced with a carcinogen called polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB) at a new hazardous waste landfill in the small, predominantly Black town of Afton.

That incident gave rise to the modern environmental justice movement. Civil rights and environmental activists soon saw a pattern when a similar fight took place in New York City a few years later. City planners unilaterally decided to move a sewage treatment plant slated for an affluent neighborhood to West Harlem. Community leaders rallied opposition to the plant, which led to the creation of WE ACT for Environmental Justice in 1988. Still, the city proceeded with the plan, promising residents that the facility would be odorless and harmless.

It’s a classic act of environmental injustice, the sort of thing activists like Corbin-Mark fought against for decades. When residents of West Harlem started noticing a foul, noxious stench wafting as far as two miles from the plant, WE ACT and the National Resources Defense Council sued the city. The lawsuit was settled in 1993 and provided roughly $1 million in environmental benefit funds, which allowed WE ACT — an all-volunteer organization at the time — to begin paying co-founder and executive director Peggy Shepard and expand her team. Today, the org counts around 20 people in its ranks.

“We decided we’re going to develop our own little NRDC in upper Manhattan,” Shepard said. “When we got the grant from the fund, the first staff person I thought of hiring was Cecil. We basically started the business in our new office, then hired three other people. It was just the five of us for a couple years.”

Vernice Miller-Travis, who cofounded WE ACT with Shepard but later moved to Washington, D.C., was impressed by Corbin-Mark, who was in his 20s at the time. “I could exhale a little, knowing that there was going to be somebody at Peggy’s side, building the organization and doing the work who cared about it as much as I did, and that I didn’t have to be right there on the spot all the time,” she says.

Shepard, who lived three blocks from Corbin-Mark in West Harlem, had met him not long before. She was out and about one Saturday and stumbled upon a block party where Corbin-Mark, who worked in the Bronx district attorney’s office, was telling an audience about environmental stewardship and explaining how the community could address the systemic issues entrenched in their neighborhood.

“I was struck by the passion and the specificity and the articulate message he was giving, so I met him and we stayed in touch,” Shepard said. “His friends and family probably thought he was crazy for leaving his good city job for a startup with ‘environmental justice’ in the name.”

The issue of environmental racism was making its first appearance in national politics when Corbin-Mark joined WE ACT. In 1994, President Bill Clinton signed an executive order directing federal agencies to consider the environmental and health impacts of their actions on low-income communities of color. While Black environmental activists considered that groundbreaking, systemic inequities like legacy pollution persisted.

Corbin-Mark always had a vision coming into focus as people tossed around ideas about implementation and approach. “Our action should not be without strategy,” he often told colleagues (and tweeted at least once). His innovative thinking and ideas are what made him accomplish so much. An exhaustive accounting of his achievements would most likely fill a book, but those who knew him best credit him with advancing more than a dozen state legislative bills addressing toxins. He was also instrumental in getting the first line items in the New York environmental protection fund, now slated for $8 million a year. And, in the months before he died, Corbin-Mark championed several clean-energy programs and initiatives that WE ACT plans to continue pursuing.

Beyond his strong relationships with several state officials, Corbin-Mark regularly forged international relationships while attending climate and environmental events from Brazil to South Africa to Indonesia. Even those who felt challenged by Corbin-Mark’s positions and disagreed with his views admired his passion and mourned his passing.

George Floyd’s killing last summer prompted Corbin-Mark to once again focus most of his energy on highlighting the connections between racial justice and environmental justice. “We have to remember that Cecil was a Black man,” Shepard said. “At the large white organizations, the higher spots don’t generally go to people of color.” The National Black Environmental Justice Network, for which Corbin-Mark served on the steering committee, was resurrected after a 15-month hiatus. Floyd’s final words — “I can’t breathe” — became a rallying cry for racial justice, a sentiment shared by anyone who’s been subjected to environmental racism. After all, African Americans are 79 percent more likely to live in neighborhoods with severe industrial pollution.

Corbin-Mark, Shepard, and other Black environmental justice pioneers long challenged the “white savior” narrative of the historically, and overwhelmingly, white environmental movement. Raya Salter, policy organizer for the New York Renews coalition that helped pass New York’s groundbreaking climate legislation, said Corbin-Mark’s upbringing in Harlem — a community dubbed the heartbeat of the Black story in America — and his role in the environmental justice space are in many ways similar to the Harlem Renaissance.

“He was kind of the James Baldwin of the environmental justice movement, because no matter what or who he encountered, he just always showed dignity and intelligence,” says Salter.

Even Beverly Wright, founder and executive director of the Deep South Center for Environmental Justice who has, with Shepard, been called the “mother of environmental justice,” echoed the idea when she repeatedly called Corbin-Mark a “renaissance man” during his memorial.

Yet even as the movement he led moved into the mainstream, Corbin-Mark was, as always, looking ahead to the next challenge. He had begun building an “energy justice” movement just before his passing. A growing body of evidence shows that racial covenants and racist city planning policies during the Jim Crow era determined which communities lived near landfills, sewage treatment plants, refineries, and other sources of industrial pollution. If clean energy is to take over the grid, Corbin-Mark questioned whether historically underserved communities would benefit.

His foresight was critical when it came to energy initiatives. A 2017 report by the NAACP outlined how governments should start considering access to energy services a basic human right. Among families living below the poverty level, Black households are more than twice as likely to experience power shut-offs than white ones. This is especially true in New York, where Corbin-Mark started a solar-installation program that would benefit underserved communities, working alongside agencies like city utility Con Edison and the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority.

“Cecil knew how politics got done and how policies could change,” said Stephan Roundtree, the northeast director at the nonprofit Vote Solar and one of many people Corbin-Mark mentored over the years. “But he was really serious about starting with what people were telling us about their lives, because he knows that’s where a just policy comes from — by really addressing the lived conditions of people on the ground.”

While punctuality was never Corbin-Mark’s strongest suit, he made a lasting impact wherever he went. To people who knew him, it seemed he was always clutching a book in one hand and his phone and keys in the other while walking to the subway station or striding toward a rental car when traveling. Details like that may seem small, even inconsequential, when looking back on the life of a pioneer like Corbin-Mark, but they further humanize a man whose life, actions, and words will serve as a reminder of the political will needed to address institutional racism and inequities woven into the fabric of this nation.

“In a social movement, we build things, we organize, we do policy and advocacy, but not everyone was a visionary,” Miller-Travis said. “Cecil was that kind of person, and we are going to miss him terribly.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline He brought ‘good trouble’ to environmental justice on Mar 5, 2021.

This post was originally published on Grist.

Racial justice and climate justice are inseparable. Few would deny this, but that wasn’t always so. For much of its history, the environmental movement has been overwhelmingly white and gave little thought to the impacts pollution and climate change had on people of color and underserved communities. The convergence of the two, which happened no more than a generation ago, came only after the tireless work of activists like Cecil Corbin-Mark.

Corbin-Mark was a towering, didactic man from Harlem who always offered criticism with love. He was equally adept at organizing his neighbors as he was lobbying policymakers. Never afraid to denounce the injustice deeply entrenched in Black and brown communities, much of his life was spent tirelessly battling the colonial mindset so many live under. Growing up in a family actively engaged in the civil rights movement, it’s no surprise that Corbin-Mark became one of the earliest champions of environmental justice, which was a novel, even radical, idea at the time.

For three decades, he demanded justice for underserved and overlooked communities, a campaign he waged until his sudden passing last October at 51. He never stopped getting into what the late civil rights activist Rep. John Lewis would call “good, necessary trouble.”

Even in a year of immeasurable grief for the Black and brown communities grappling with police brutality and a disproportionate share of COVID-19 deaths, Corbin-Mark remained steadfast in the struggle to eliminate toxic pollution, address systemic racism, and implement equitable climate and energy policies. He scored a key victory, too, in helping pass landmark climate legislation that would not only commit his home state of New York to net-zero emissions by 2050, but require at least 35 percent of state energy and climate spending go to pollution-burdened communities.

Corbin-Mark left a legacy that many in the movement, veterans and newcomers alike, will never forget — something three members of the House of Representatives specifically cited when they introduced a resolution honoring the activist for his life’s work. As one of its first employees, Corbin-Mark helped shepherd the growth of WE ACT for Environmental Justice, which was among the earliest organizations to fight environmental racism. Its virtual memorial for Corbin-Mark drew more than 400 people, offering compelling proof of his impact. Many hailed him as a visionary and gifted policy wonk focused on making energy justice the next front in the ongoing campaign for environmental justice.

Among the most lamentable things about his passing is that he didn’t live to see President Biden pass a slew of executive orders centering environmental justice in his climate and economic agendas. Many of Corbin-Mark’s colleagues credit him with helping carve the path that led to such a historic moment. That his life’s work was inextricably tied to the rise of the movement that made it happen is not lost on those who saw him tirelessly defend marginalized communities.

“The time he grew into who he became at WE ACT tracks with how the environmental justice movement has grown,” says 2019 Grist 50 Fixer Kerene Tayloe, director of federal legislative affairs at WE ACT. She tears up recalling Corbin-Mark’s impact on her life. “His ability to understand the importance of policy at the city level, at the state level, and at the federal level was instrumental in changing and preparing us for where we are right now. I just wish he was here to see the day [Biden’s] executive orders came out.”

Corbin-Mark dedicated most of his life to serving communities of color, particularly fighting against the systemic inequities baked into the daily life of his neighborhood. The disparities are evident in even seemingly minute things: Many people in Harlem — mostly low-income people of color — must endure the pernicious summer heat of New York City, while white and wealthier residents just blocks away sit comfortably in their expensive, air-conditioned apartments.

Bringing these connections to what has historically been a white-dominated movement was never an easy endeavor. About a decade after the civil rights movement in the 1960s, the first battle against environmental racism — though the term didn’t exist until years later — began taking shape. State officials in North Carolina decided to dump soil laced with a carcinogen called polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB) at a new hazardous waste landfill in the small, predominantly Black town of Afton.

That incident gave rise to the modern environmental justice movement. Civil rights and environmental activists soon saw a pattern when a similar fight took place in New York City a few years later. City planners unilaterally decided to move a sewage treatment plant slated for an affluent neighborhood to West Harlem. Community leaders rallied opposition to the plant, which led to the creation of WE ACT for Environmental Justice in 1988. Still, the city proceeded with the plan, promising residents that the facility would be odorless and harmless.

It’s a classic act of environmental injustice, the sort of thing activists like Corbin-Mark fought against for decades. When residents of West Harlem started noticing a foul, noxious stench wafting as far as two miles from the plant, WE ACT and the National Resources Defense Council sued the city. The lawsuit was settled in 1993 and provided roughly $1 million in environmental benefit funds, which allowed WE ACT — an all-volunteer organization at the time — to begin paying co-founder and executive director Peggy Shepard and expand her team. Today, the org counts around 20 people in its ranks.

Cecil Corbin-Mark at WE ACT’s 25th anniversary event in 2013. Courtesy of WE ACT

“We decided we’re going to develop our own little NRDC in upper Manhattan,” Shepard said. “When we got the grant from the fund, the first staff person I thought of hiring was Cecil. We basically started the business in our new office, then hired three other people. It was just the five of us for a couple years.”

Vernice Miller-Travis, who cofounded WE ACT with Shepard but later moved to Washington, D.C., was impressed by Corbin-Mark, who was in his 20s at the time. “I could exhale a little, knowing that there was going to be somebody at Peggy’s side, building the organization and doing the work who cared about it as much as I did, and that I didn’t have to be right there on the spot all the time,” she says.

Shepard, who lived three blocks from Corbin-Mark in West Harlem, had met him not long before. She was out and about one Saturday and stumbled upon a block party where Corbin-Mark, who worked in the Bronx district attorney’s office, was telling an audience about environmental stewardship and explaining how the community could address the systemic issues entrenched in their neighborhood.

“I was struck by the passion and the specificity and the articulate message he was giving, so I met him and we stayed in touch,” Shepard said. “His friends and family probably thought he was crazy for leaving his good city job for a startup with ‘environmental justice’ in the name.”

The issue of environmental racism was making its first appearance in national politics when Corbin-Mark joined WE ACT. In 1994, President Bill Clinton signed an executive order directing federal agencies to consider the environmental and health impacts of their actions on low-income communities of color. While Black environmental activists considered that groundbreaking, systemic inequities like legacy pollution persisted.

Corbin-Mark always had a vision coming into focus as people tossed around ideas about implementation and approach. “Our action should not be without strategy,” he often told colleagues (and tweeted at least once). His innovative thinking and ideas are what made him accomplish so much. An exhaustive accounting of his achievements would most likely fill a book, but those who knew him best credit him with advancing more than a dozen state legislative bills addressing toxins. He was also instrumental in getting the first line items in the New York environmental protection fund, now slated for $8 million a year. And, in the months before he died, Corbin-Mark championed several clean-energy programs and initiatives that WE ACT plans to continue pursuing.

Beyond his strong relationships with several state officials, Corbin-Mark regularly forged international relationships while attending climate and environmental events from Brazil to South Africa to Indonesia. Even those who felt challenged by Corbin-Mark’s positions and disagreed with his views admired his passion and mourned his passing.

George Floyd’s killing last summer prompted Corbin-Mark to once again focus most of his energy on highlighting the connections between racial justice and environmental justice. “We have to remember that Cecil was a Black man,” Shepard said. “At the large white organizations, the higher spots don’t generally go to people of color.” The National Black Environmental Justice Network, for which Corbin-Mark served on the steering committee, was resurrected after a 15-month hiatus. Floyd’s final words — “I can’t breathe” — became a rallying cry for racial justice, a sentiment shared by anyone who’s been subjected to environmental racism. After all, African Americans are 79 percent more likely to live in neighborhoods with severe industrial pollution.

Corbin-Mark, Shepard, and other Black environmental justice pioneers long challenged the “white savior” narrative of the historically, and overwhelmingly, white environmental movement. Raya Salter, policy organizer for the New York Renews coalition that helped pass New York’s groundbreaking climate legislation, said Corbin-Mark’s upbringing in Harlem — a community dubbed the heartbeat of the Black story in America — and his role in the environmental justice space are in many ways similar to the Harlem Renaissance.

“He was kind of the James Baldwin of the environmental justice movement, because no matter what or who he encountered, he just always showed dignity and intelligence,” says Salter.

Even Beverly Wright, founder and executive director of the Deep South Center for Environmental Justice who has, with Shepard, been called the “mother of environmental justice,” echoed the idea when she repeatedly called Corbin-Mark a “renaissance man” during his memorial.

Yet even as the movement he led moved into the mainstream, Corbin-Mark was, as always, looking ahead to the next challenge. He had begun building an “energy justice” movement just before his passing. A growing body of evidence shows that racial covenants and racist city planning policies during the Jim Crow era determined which communities lived near landfills, sewage treatment plants, refineries, and other sources of industrial pollution. If clean energy is to take over the grid, Corbin-Mark questioned whether historically underserved communities would benefit.

His foresight was critical when it came to energy initiatives. A 2017 report by the NAACP outlined how governments should start considering access to energy services a basic human right. Among families living below the poverty level, Black households are more than twice as likely to experience power shut-offs than white ones. This is especially true in New York, where Corbin-Mark started a solar-installation program that would benefit underserved communities, working alongside agencies like city utility Con Edison and the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority.

“Cecil knew how politics got done and how policies could change,” said Stephan Roundtree, the northeast director at the nonprofit Vote Solar and one of many people Corbin-Mark mentored over the years. “But he was really serious about starting with what people were telling us about their lives, because he knows that’s where a just policy comes from — by really addressing the lived conditions of people on the ground.”

While punctuality was never Corbin-Mark’s strongest suit, he made a lasting impact wherever he went. To people who knew him, it seemed he was always clutching a book in one hand and his phone and keys in the other while walking to the subway station or striding toward a rental car when traveling. Details like that may seem small, even inconsequential, when looking back on the life of a pioneer like Corbin-Mark, but they further humanize a man whose life, actions, and words will serve as a reminder of the political will needed to address institutional racism and inequities woven into the fabric of this nation.

“In a social movement, we build things, we organize, we do policy and advocacy, but not everyone was a visionary,” Miller-Travis said. “Cecil was that kind of person, and we are going to miss him terribly.”

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

If you’ve noticed more people rooting around their yards for dandelion greens or picking fruit in the local park, there’s a good chance it’s because of Alexis Nikole Nelson.

On TikTok, Nelson charms her 600,000-odd followers with raps about ethically foraging for ramps (or finding a substitute because, you know, they’re at risk of becoming endangered); tips for telling the difference between Queen Anne’s lace and its evil twin, hemlock; and culinary delights like seaweed panna cotta. It’s enough to make you want to look around your own yard for field onions and hairy bittercress so you can whip up scallion pancakes. Nelson does this all with sustainability in mind, encouraging her followers to eat invasive and pervasive plants.

For the uninitiated, foraging simply means identifying and gathering mushrooms, herbs, nuts, fruits and other food. Sure, you could go to your local grocery store, but foraging offers several advantages beyond being a great social-distancing activity. It means eating with the seasons, adding variety to your diet, and becoming less reliant on the agricultural industrial complex and monocropping that’s led to environmental disasters like the dust bowl.

Nelson’s interest in foraging sprouted during a childhood spent in the family garden. Her mother would often quiz her on plants while Nelson ran around with a toy trowel, digging holes for bulbs. Nelson soon found herself fascinated by the weeds. “The things I was most interested in were the useful plants that were not there on purpose,” she says. “I didn’t completely understand why they weren’t ‘on purpose’ despite being useful.”

After graduating from Ohio State University, Nelson’s hobby approached obsession when she found herself broke while between jobs. Instead of spending six bucks(!) on supermarket greens, she harvested curly dock and wood sorrel to make delicious (and free!) salads. Nelson grew more culinarily adventurous, started composting, and gave more thought to sustainability in the kitchen. She forages for about 10 percent of her food through the winter. Come summer, she’ll go days eating only what she’s found, with the exception of olive oil because, she says, making it herself is a real time-suck.

These days, Nelson calls herself @BlackForager on Instagram and Facebook, because she didn’t see faces that looked like hers. “Because of my reach, I have started finding people who look like me in this space, and that’s been beautiful,” she says. TikTok recently took note, naming her one of its inaugural Black TikTok Trailblazers in February. In the coming year, she’d like to put out longer content on her YouTube channel.

Fix chatted with Nelson about drawing foraging inspiration from the past, dispelling some common misconceptions, and how gathering your own food is a revolutionary act. Her comments have been edited for length and clarity.

Q.How is forging and cooking with what you’ve harvested a historical practice?

A.I love diving into old cookbooks, especially those out of the Appalachian region, because they often focus a lot on making do with what was around. One example that I like to talk about is pokeweed — a plant that is pretty much universally considered a weed, and a noxious one at that.

On the other hand, you have folks like my dad’s side of the family saying, “Excuse me, poke salad is a very popular springtime dish made with pokeweed shoots.” It was just a matter of knowing the process of blanching them to make sure that they are rendered completely safe. Poke salad is a dish that could very easily fall out of the national consciousness if folks who know about it don’t teach their kids about it or commit it to a space where it can stay forever.

I think a lot of us have stories about a grandparent or a parent sharing what is, honestly, ancient knowledge but it isn’t necessarily making the jump from generation to generation. We risk losing a lot of food knowledge, especially food knowledge held by the Indigenous and Black communities.

Q.What are some common misconceptions about foraging?

A.The biggest hurdle for a lot of folks is the idea that foraging can happen in city spaces. You just have to make informed decisions. A lot of folks think that I live in the middle of the woods. I don’t. I live on the outskirts of Columbus, Ohio.

Foraging is possible for me, but I’m also the kind of weirdo who will ask the parks and rec department questions and do research on parks where gathering things is — I don’t even want to say this — legal. The two types of parks I see are parks where foraging is explicitly illegal and parks where foraging is not mentioned at all.

The next thing a lot of folks have apprehension about is where it is safe to forage. I can’t give everyone an exact answer unless they also happen to live in Columbus. No one wants to do homework and I get it, but I’d also rather be safe than sorry.

A lot of people say, “I’m never going to get to a point where I know as many plants as you, so there’s no point in me starting now,” which is so not true. I think people believe I woke up one day with all of this knowledge. I’m still learning every single day, and I have been doing this for almost two-and-a-half decades.

Q.How do you see foraging as a revolutionary act?

A.Foraging has been a part of Indigenous food ways and the food ways of pretty much every underserved community, whether those people were enslaved or just not very high on the socioeconomic scale.

After the Civil War, it became apparent that it would become harder to keep Black people on plantations as cheap labor. Folks realized that one way of denying Black people other options was to deny them the food ways they could use not only to sustain themselves but to prepare and sell food to others as a way of building wealth — not just surviving, but thriving. That’s when we saw the nation’s first round of laws barring foraging in public spaces. Doing so was a civil offense everywhere in the South until after the Civil War, when it became a criminal offense. That affected Indigenous people, who suddenly had their access to food ways taken away. The law also impacted a lot of poor white people.

@alexisnikole Reply to @jaxwellmones #foraging

For me, being a person of color out in the world foraging is super revolutionary, because it was something that was very intentionally taken out of my ancestors’ hands. We still have a ton of laws discouraging people from foraging despite the fact that the handful of people doing it are not making horrible dents in these natural spaces.

Q.Have you seen more people reclaiming food sovereignty through foraging or gardening?

A.Within the Black community, I’ve seen a huge push for farming as a way of reclaiming food sovereignty. I’ve noticed folks, especially women, like @TheHillbillyAfrican on Instagram, buying swaths of land and taking complete control of their food ways. Teaching farms are showing the next generation of Black children what growing your own food is like, what a balanced diet looks like. They’re getting their hands in the dirt, so they foster a love of this early.

That’s been slowly creeping on the up and up for a really long time, but just in the last two years, I’ve really seen a boom of Black folks saying, “If we’re not going to get included in these conversations about food sovereignty within cities, we’re just going to take care of our own ourselves.”

I’m in a neighborhood that is historically Black. A community garden opened last year. Students from OSU come down and volunteer, but all of the kids from the neighborhood who participate are Black. I love that. Nothing makes me happier than walking down there and being around people who look like me and little kids who are excited to be here, digging in the dirt and learning more about where their food comes from. They’re laying strong foundations for themselves and future generations and they don’t even know it. They’re just having fun.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline This TikTok star makes foraging a fun — and revolutionary — practice on Mar 4, 2021.

This post was originally published on Grist.

Every eco-conscious consumer has felt the frustration of trying to make the least climate-ruining decisions. Nothing you buy is really good for the planet — every new purchase carries a carbon cost. So many factors go into determining the environmental and social impact of everything on your shopping list that even the smallest choices can become agonizing. How are you to know whether cotton really is better than polyester? Whether local or organic food is preferable? Whether GMO means anything at all? A mind-boggling array of factors can inform every decision, so for reassurance, people often turn to trusted brands and recognizable — or at least understandable —labels.