This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Venezuelan National Assembly President Jorge Rodríguez declared Monday that the government will mobilize multilateral organizations and international law firms to repatriate citizens detained abroad. He accused the United States of “kidnapping” Venezuelan migrants and collaborating with El Salvador in a “modern slave trade.”

The announcement came after reports that more than 200 Venezuelan migrants were transferred from U.S. custody to prisons in El Salvador based on unproven allegations of ties to the Aragua Train criminal gang.

The post Venezuela Vows ‘All Strategies’ To Repatriate Citizens appeared first on PopularResistance.Org.

This post was originally published on PopularResistance.Org.

This content originally appeared on ProPublica and was authored by ProPublica.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Guantánamo Bay has been a fiendish experiment in US law for decades. The fiendishness lies in the subversion. Operating as a naval base in Cuba, this contentious facility has been the site and location for the cruelties of paranoia and empire, a place where such laws as due process are subverted, and the presumption to innocence soiled. In this contorted way, the civilian and military branches have mingled and corrupted, the result proving a nightmare for legal authorities keen to ensure that such a facility does, at the very least, observe that sad, dusty relic known as the rule of law.

Legal sharpshooters have been baffled by the latest experiment with the facility, this time from the Trump administration and its efforts to use it as a detention centre for unwanted migrants. On January 29, the US president directed the Secretaries of Defense and Homeland Security “to take all appropriate actions to expand the Migrant Operations Center at Naval Station Guantanamo Bay to full capacity to provide additional detention space for high-priority criminal aliens unlawfully present in the United States”. Furthermore, the secretaries were directed “to address attendant immigration enforcement needs identified” by the departments. The first flight transferring migrants from US soil to the facility took place on February 4 this year.

The intention is to house up to 30,000 people, but it is already clear that not all, contrary to what the president claims, are “the worst criminal aliens threatening the American people.” Some have been found to be of a “low-threat” category, hardly the sort to terrify the peace of mind of your average US citizen. Yet again, we find himself inhabiting a world of dismal illusions.

Such an authorisation can hardly be said to fall within the all too conveniently expansive 2001 Authorization for the Use of Military Force (AUMF), which focuses on the interminable prosecution of the formerly known Global War on Terror. The MOC is its own beast, a separate instrument controversial for “housing” (as opposed to “detaining”) its residents. It is located on the Leeward side of the base and was created to house Caribbean migrants interdicted at sea in the 1990s.

The entities relevant to running the MOC are the State Department’s Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration (PRM) and the US Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) responsible to the Department of Homeland Security. Interdicted migrants are assessed to see if they deserve “protected” status, one that is granted if the individual has a genuine fear of harm arising if they are returned to their country or origin. Historically, during the phase of their assessment, migrants receive a basic set of services in healthcare, housing, education, and job training.

The use of the island to deal with immigrants has been a blighted practice undertaken by US administrations since the 1970s. The Ford and Carter administrations held Haitians at the base as they awaited asylum interviews. After a cessation of immigration detention onsite under the Reagan administration, the unsavoury practice was resumed in 1991. Again involving Haitians, only this time in greater numbers, given the military coup, some 12,500 were transferred to a shoddy, makeshift camp. Under Bill Clinton’s presidency, the camp was emptied, but the rights of those interdicted was systematically stripped to enable them to be repatriated. In 1994, the camp, in all its squalid ingloriousness, was reopened to house Cubans and Haitians in their tens of thousands.

The issue of valid authorisation is not a mere semantic quibble. Trump’s actions have consequential disturbances to the rule of law. The administration is seemingly pushing, not merely a smudging of the categories in terms of dealing with migrants, but their obliteration. What we are left with is a nasty mixture of terror and malfeasance, a point that utterly repudiates basic protections offered by the UN Refugee Convention.

Nor is it clear whether the administration can legally carry out these measures. The MOC migrants being transferred will not be deprived of legal rights afforded them under the US Constitution, which include access to the judicial system and legal counsel, due process protections which cover arbitrary or indefinite detention, the right to appropriate conditions of confinement, and the right to seek release from unlawful detention. It is also important to distinguish those immigrants interdicted at sea who seek asylum in the United States, and those already on US soil. A case is currently pending on the issue before US Judge Carl Nichols in Washington, D.C., though a court date is yet to be set.

In terms of both cost and logistics, this detention measure is also untenable. It has been estimated that the average cost for an immigration detention bed will be quintupled from its current annual total of $57,378. Ensuring access to legal counsel and guaranteeing humane treatment will also present a nightmarish scenario for the authorities, given the scale of the expansion sought by Trump.

So far, lawyers from the Justice Department have unconvincingly claimed that the limited availability of phone calls to counsel located off the base was a “reasonable and consistent” measure when it comes to the “temporary staging” of migrants with final deportation orders to other countries.

The Trump administration’s waspish approach to unwanted immigrants replicates the pattern of deterrence and demonisation used by other countries (member states in the European Union and Australia comes to mind) that have treated unwanted arrivals as an interchangeable commodity with political objects and national security: the terrorist, the hardened criminal, the deviant, the immoral figure best barred from entering their borders. But at the very least, a firmly established legal system, if mobilised correctly, has some prospect of sinking this hideous experiment.

The post Fiendish Experiments: Trump’s Guantánamo Bay Migrant Detentions first appeared on Dissident Voice.This post was originally published on Dissident Voice.

The U.S. military transported 17 new immigrant detainees to the Guantánamo Bay military base on Sunday, just before efforts to jail an anticipated 30,000 immigrants in tent camps at the base were halted over concerns the makeshift facilities don’t meet ICE’s detention standards. Now the private federal contractor behind the Guantánamo detention site is under renewed scrutiny.

This post was originally published on Latest – Truthout.

The U.S. military transported 17 new immigrant detainees to the Guantánamo Bay military base on Sunday, just before efforts to jail an anticipated 30,000 immigrants in tent camps at the base were halted over concerns the makeshift facilities don’t meet ICE’s detention standards. Now the private federal contractor behind the Guantánamo detention site is under renewed scrutiny. Investigative journalist José Olivares shares what we know about Akima Infrastructure Protection, an Alaska Native corporation that counts among its myriad federal contracts immigration detention facilities across the United States, including some that are currently under investigation for human rights abuses. The lack of transparency when it comes to the company’s practices and the expansion of migrant detention at a high-security location like Guantánamo means that questions remain over current conditions and even the exact number of people who have been incarcerated there, explains Olivares.

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Venezuelan Minister for Internal Affairs, Justice and Peace Diosdado Cabello received 177 Venezuelans rescued from the US military base in Guantánamo Bay that illegally occupies Cuban territory. Cabello explained that the operation was the result of a request by the Venezuelan government negotiated with the US government. The New York Times (NYT) reported that one migrant was sent back to the US.

The 177 migrants arrived in Venezuela near midnight on Thursday, February 20, on a Conviasa Airbus 340-200 passenger jet at the Simón Bolívar International Airport in Maiquetia, La Guaira state.

The post Migrants Rescued From Guantánamo Arrive In Venezuela appeared first on PopularResistance.Org.

This post was originally published on PopularResistance.Org.

We look at a victory for immigrant rights, after a federal judge temporarily blocked the U.S. government from deporting three Venezuelan men to Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, where the Trump administration has started to send thousands of immigrants for detention. Our guest, Baher Azmy, legal director for the Center for Constitutional Rights, sought an emergency order to protect the three men, who had been held for about a year at the Otero detention center. The men say they left Venezuela to request asylum in the United States but were rejected. When they saw others from the detention center transferred to Guantánamo, they feared they could be next and asked the judge to preemptively block their transfer. This all comes as the Trump administration recently withdrew temporary protected status for Venezuelans living in the United States. “We decided we had to move and prevent their transfer, their rendition, to the lawless space in Guantánamo,” says Azmy. We also speak with Vince Warren, the executive director of the Center for Constitutional Rights. Warren says that the United States is “facing a constitutional crisis on a range of issues, and it’s just not clear to any of us whether this administration will actually comply with the rule of law in any context.”

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Guantánamo represents a place beyond the reach of morality and the law, where America’s most dangerous enemies can be thrown, never to be seen again.

This post was originally published on Dissent Magazine.

On Wednesday, President Donald Trump signed an executive order to “expand” a migrant detention center located within the Guantánamo Bay Naval Base. Prior to the release of the executive order, the administration announced that 30,000 migrants would be detained at Guantánamo.

“We have 30,000 beds in Guantanamo to detain the worst criminal illegal aliens threatening the American people. This will double our capacity immediately,” Trump said.

But according to Department of Homeland Security and Navy documents from 2021 and 2022 reviewed by Drop Site News, the Trump administration may not be able to detain that high of a number of migrants at the facility — at least not immediately.

The post Biden Gave Trump The Blueprint To Lock Up 30,000 Migrants appeared first on PopularResistance.Org.

This post was originally published on PopularResistance.Org.

On January 10th, one day before the 23rd anniversary of its opening, a much-anticipated hearing was set to take place at the Guantánamo Bay Detention Facility on the island of Cuba. After nearly 17 years of pretrial litigation, the prosecution of Khalid Sheikh Mohammed (KSM), the “mastermind” of the devastating attacks of September 11, 2001, seemed poised to achieve its ever-elusive goal of…

This post was originally published on Latest – Truthout.

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Eleven Yemeni men imprisoned without charge or trial at the Guantánamo Bay detention center for more than two decades have just been released to Oman to restart their lives. This latest transfer brings the total number of men detained at Guantánamo down to 15. Civil rights lawyers Ramzi Kassem and Pardiss Kebriaei, who have each represented many Guantánamo detainees, including some of the men just released, say closing the notorious detention center “has always been a question of political will,” and that the Biden administration must take action to free the remaining prisoners and “end of the system of indefinite detention” as soon as possible.

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

The United States sent 11 Yemeni detainees at the Guantanamo Bay detention facility to Oman, the Pentagon said on Monday, leaving 15 people at the infamous detention centre.

The transfer was initially slated for October 2023 but the 7 October 2023 Hamas-led attack on southern Israel and Israel’s subsequent war on Gaza delayed the transfer, according to an admission from US officials in May last year.

“The United States appreciates the willingness of the government of Oman and other partners to support ongoing US efforts focused on responsibly reducing the detainee population and ultimately closing the Guantanamo Bay facility,” the US military said in a statement.

The post US Transfers 11 Detainees Out Of Guantanamo Bay Prison appeared first on PopularResistance.Org.

This post was originally published on PopularResistance.Org.

This content originally appeared on VICE News and was authored by VICE News.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Listen to the Talking China In Eurasia podcast

Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Google | YouTube

Welcome back to the China In Eurasia Briefing, an RFE/RL newsletter tracking China’s resurgent influence from Eastern Europe to Central Asia.

I’m RFE/RL correspondent Reid Standish and here’s what I’m following right now.

As Huthi rebels continue their assault on commercial shipping in the Red Sea, the deepening crisis is posing a fresh test for China’s ambitions of becoming a power broker in the Middle East – and raising questions about whether Beijing can help bring the group to bay.

Finding Perspective: U.S. officials have been asking China to urge Tehran to rein in Iran-backed Huthis, but according to the Financial Times, American officials say that they have seen no signs of help.

Still, Washington keeps raising the issue. In weekend meetings with Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi in Bangkok, U.S. national-security adviser Jake Sullivan again asked Beijing to use its “substantial leverage with Iran” to play a “constructive role” in stopping the attacks.

Reuters, citing Iranian officials, reported on January 26 that Beijing urged Tehran at recent meetings to pressure the Huthis or risk jeopardizing business cooperation with China in the future.

There are plenty of reasons to believe that China would want to bring the attacks to an end. The Huthis have disrupted global shipping, stoking fears of global inflation and even more instability in the Middle East.

This also hurts China’s bottom line. The attacks are raising transport costs and jeopardizing the tens of billions of dollars that China has invested in nearby Egyptian ports.

Why It Matters: The current crisis raises some complex questions for China’s ambitions in the Middle East.

If China decides to pressure Iran, it’s unknown how much influence Tehran actually has over Yemen’s Huthis. Iran backs the group and supplies them with weapons, but it’s unclear if they can actually control and rein them in, as U.S. officials are calling for.

But the bigger question might be whether this calculation looks the same from Beijing.

China might be reluctant to get too involved and squander its political capital with Iran on trying to get the Huthis to stop their attacks, especially after the group has announced that it won’t attack Chinese ships transiting the Red Sea.

Beijing is also unlikely to want to bring an end to something that’s hurting America’s interests arguably more than its own at the moment.

U.S. officials say they’ll continue to talk with China about helping restore trade in the Red Sea, but Beijing might decide that it has more to gain by simply stepping back.

1. ‘New Historical Heights’ For China And Uzbekistan

Uzbek President Shavkat Mirziyoev made a landmark three-day visit to Beijing, where he met with Xi, engaged with Chinese business leaders, and left with an officially upgraded relationship as the Central Asian leader increasingly looks to China for his economic future.

The Details: As I reported here, Mirziyoev left Uzbekistan looking to usher in a new era and returned with upgraded diplomatic ties as an “all-weather” partner with China.

The move to elevate to an “all-weather comprehensive strategic partnership” from a “comprehensive strategic partnership” doesn’t come with any formal benefits, but it’s a clear sign from Mirziyoev and Xi on where they want to take the relationship between their two countries.

Before going to China for the January 23-25 trip, Mirziyoev signed a letter praising China’s progress in fighting poverty and saying he wanted to develop a “new long-term agenda” with Beijing that will last for “decades.”

Beyond the diplomatic upgrade, China said it was ready to expand cooperation with Uzbekistan across the new energy vehicle industry chain, as well as in major projects such as photovoltaics, wind power, and hydropower.

Xi and Mirzoyoev also spoke about the long-discussed China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan railway, with the Chinese leader saying that work should begin as soon as possible, athough no specifics were offered and there are reportedly still key disputes over how the megaproject will be financed.

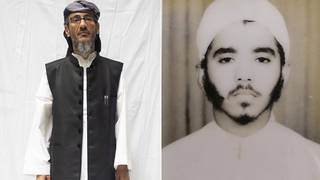

2. The Taliban’s New Man In Beijing

In a move that could lay the groundwork for more diplomatic engagement with China, Xi received diplomatic credentials from the Taliban’s new ambassador in Beijing on January 25.

What You Need To Know: Mawlawi Asadullah Bilal Karimi was accepted as part of a ceremony that also received the credential letters of 42 new envoys. Karimi was named as the new ambassador to Beijing on November 24 but has now formally been received by Xi, which is another installment in the slow boil toward recognition that’s under way.

No country formally recognizes the Taliban administration in Afghanistan, but China – along with other countries such as Pakistan, Russia, and Turkmenistan – have appointed their own envoys to Kabul and have maintained steady diplomatic engagement with the group since it returned to power in August 2021.

Formal diplomatic recognition for the Taliban still looks to be far off, but this move highlights China’s strategy of de-facto recognition that could see other countries following its lead, paving the way for formal ties down the line.

3. China’s Tightrope With Iran and Pakistan

Air strikes and diplomatic sparring between Iran and Pakistan raised difficult questions for China and its influence in the region, as I reported here.

Both Islamabad and Tehran have since moved to mend fences, with their foreign ministers holding talks on January 29. But the incident put the spotlight on what China would do if two of its closest partners entered into conflict against one another.

What It Means: The tit-for-tat strikes hit militant groups operating in each other’s territory. After a tough exchange, both countries quickly cooled their rhetoric – culminating in the recent talks held in Islamabad.

And while Beijing has lots to lose in the event of a wider conflict between two of its allies, it appeared to remain quiet, with only a formal offer to mediate if needed.

Abdul Basit, an associate research fellow at Singapore’s S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, told me this approach reflects how China “shies away from situations like this,” in part to protect its reputation in case it intervenes and then fails.

Michael Kugelman, the director of the Wilson Center’s South Asia Institute, added that, despite Beijing’s cautious approach, China has shown a willingness to mediate when opportunity strikes, pointing to the deal it helped broker between Iran and Saudi Arabia in March.

“It looks like the Pakistanis and the Iranians had enough in their relationship to ease tensions themselves,” he told me. “So [Beijing] might be relieved now, but that doesn’t mean they won’t step up if needed.”

China’s Odd Moment: What do the fall of the Soviet Union and China’s slowing economy have in common? The answer is more than you might think.

Listen to the latest episode of the Talking China In Eurasia podcast, where we explore how China’s complicated relationship with the Soviet Union is shaping the country today.

Invite Sent. Now What? Ukraine has invited Xi to participate in a planned “peace summit” of world leaders in Switzerland, Reuters reported, in a gathering tied to the second anniversary of Russia’s invasion.

Blocked, But Why? China has suspended issuing visas to Lithuanian citizens. Foreign Minister Gabrielius Landsbergis confirmed the news and told Lithuanian journalists that “we have been informed about this. No further information has been provided.”

More Hydro Plans: Kyrgyzstan’s Ministry of Energy and the China National Electric Engineering Company signed a memorandum of cooperation on January 24 to build a cascade of power plants and a new thermal power plant.

There’s no official word, but it’s looking like veteran diplomat Liu Jianchao is the leading contender to become China’s next foreign minister.

Wang Yi was reassigned to his old post after Qin Gang was abruptly removed as foreign minister last summer, and Wang is currently holding roles as both foreign minister and the more senior position of director of the Chinese Communist Party Central Committee Foreign Affairs Commission Office.

Liu has limited experience engaging with the West but served stints at the Communist Party’s anti-corruption watchdog and currently heads a party agency traditionally tasked with building ties with other communist states.

It also looks like he’s being groomed for the role. He recently completed a U.S. tour, where he met with top officials and business leaders, and has also made visits to the Middle East.

That’s all from me for now. Don’t forget to send me any questions, comments, or tips that you might have.

Until next time,

Reid Standish

If you enjoyed this briefing and don’t want to miss the next edition, subscribe here. It will be sent to your inbox every other Wednesday.

This content originally appeared on News – Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty and was authored by News – Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Nothing on the horizon now threatens the end of the U.S. economic blockade of Cuba. Critical voices inside the United States and beyond fall flat; nothing is in the works, it seems. Recently, however, the United Nations put forth a denunciation that carries unusual force, mainly because of the UN’s legal authority and its practical More

The post UN Forcefully Hits at US Blockade of Cuba and Prison in Guantanamo appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

This content originally appeared on CounterPunch.org and was authored by W. T. Whitney.

The United Nation’s special rapporteur on counterterrorism and human rights, Fionnuala Ní Aoláin, published an exhaustive investigation this week into human rights abuses at Guantánamo Bay. Following a historic visit to the detention center and interviews with current and former detainees, victims of the 9/11 attacks, and human rights lawyers, the report details delayed justice for the victims of terrorist attacks and ongoing injustice for the victims of torture.

At the core of the report is the problem of inexplicable indefinite detention. “Arbitrariness pervades the entirety of the Guantánamo detention infrastructure — rendering detainees vulnerable to human rights abuse and contributing to conditions, practices, or circumstances that lead to arbitrary detention,” the report says. Life beyond Guantánamo, for some men, is just another Guantánamo. Those who cannot be repatriated are instead sent to a “third” country like Kazakhstan, where former detainees have been met with more arbitrary detention, Ní Aoláin found.

The special rapporteur highlighted Kazakhstan and the United Arab Emirates as two countries of “egregious” concern where men have been sent to another form of prison. “In Kazakhstan former detainees effectively remain under house arrest and are unable to live a normal and dignified life due to the secondary security measures put in place post transfer,” she wrote. In the UAE, Ní Aoláin found “multiple former detainees were subject to arbitrary detention and torture, and one remains detained in incommunicado detention.”

The U.N. investigation found that the men released from Guantánamo in resettlement deals have not been given proper legal status by their host countries in 30 percent of documented cases. This lack of asylum risks “precluding them and their families from access to certain public benefits, health care, education, as well as foreign travel, or a path to citizenship, all of which are fundamental entitlements under international human rights law.”

Early this year, an investigation by The Intercept revealed that former Guantánamo prisoner Sabri al-Qurashi had been left without legal status since his relocation from Guantánamo to Kazakhstan in late 2014. Over nearly a decade in Kazakhstan, his treatment has only gotten worse, and he has become increasingly desperate. “I have no official status, no ID card, no right to work or education, and no right to see my family,” al-Qurashi said. Without a basic ID, he is unable to send or receive money, packages, or mail. When he wants to leave his apartment, he must call the Red Crescent office and ask for his assigned chaperone to accompany him. Since being freed, he has not been allowed to reunite with his family or his wife in Yemen, in conflict with the State Department’s negotiated resettlement deal, which was supposed to provide stability and possible family reunification.

“You have no rights,” al-Qurashi said he was told by Kazakh authorities. He was not allowed to press charges against a man who attacked him in the street, leaving him with permanent facial paralysis.

Now Muhammad Ali Husayn Khanayna, the only other former Guantánamo prisoner in Kazakhstan who is still alive, has come forward about his living conditions. “Soon, I will complete 10 years under the arbitrariness of the Kazakh government in a remote city for no reason,” he told The Intercept. He confirmed that he, too, has never been given documentation of residence, an ID, or his passport. “They treat us as if we were criminals who entered the country without their choice,” Khanayna said. Both al-Qurashi and Khanayna told The Intercept that Kazakh officials threatened to send them back to Yemen. “We were handed over by the American government to the militias of Kazakhstan,” Khanayna said. “Not a government that has international law or a law that protects the citizens.”

The U.N. report calls for the situation of the men “arbitrarily detained” in Kazakhstan, the UAE, and any other country with a “serious violation of human rights” to be “urgently addressed.” The U.S. should facilitate their resettlement again in a new host country, Ní Aoláin argues.

“There is a legal and moral obligation for the U.S. government to use all of its diplomatic and legal resources to facilitate (re)transfer of these men, with meaningful assurance and support to other countries,” she concludes.

A State Department representative previously told The Intercept that the U.S. government does not agree with the characterization that it has a “legal and moral” obligation to the resettled detainees. “Once security assurances have expired, and pending any specific renegotiation of assurances, it largely falls to the discretion of the host country to determine what security measures they continue to implement,” Vincent Picard said when asked for comment on the former detainees in Kazakhstan.

As al-Qurashi and Khanayna have been stuck in stateless purgatory for nearly a decade, some of the recommendations of the U.N. report come far too late. The report strongly recommends that for all resettlements and repatriations, “a formal and effective follow-up system be established as part of the remedial obligations owed by the U.S. government.” Had a system like that been in place when they were transferred, the Guantánamo detainees in Kazakhstan could have received some assistance. In 2015, they told VICE News that their mistreatment began as soon as they stepped off the plane in the former Soviet country.

“This was a mistake by the Americans in the beginning, and the Americans will not be able to change our situation inside this country,” Khanayna told The Intercept. “They only have to get us out of here.” He said he would prefer to be transferred to an Arab country like Qatar because it has a reputation of treating Guantánamo prisoners well.

“The Kazakh government is a criminal government. It has treated us like animals,” al-Qurashi said in response to the new U.N. findings. “I’m hurting from my heart.”

This content originally appeared on The Intercept and was authored by Elise Swain.

The so-called “war on terror,” initiated by the U.S. and its global allies in response to the 9/11 attacks in 2001, did not so much change the rules of warfare as throw them out of the window.

In the aftermath of 9/11 and the ensuing wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, the Geneva Convention on the treatment of prisoners of war was virtually abandoned when the U.S. and its allies detained hundreds of thousands of men, women and children, mainly civilians. The use of torture and indefinite arbitrary detention became defining features of the war on terror.

Intelligence yielded from the use of torture was not particularly effective, and experimentation on human subjects was an element of the process. Guantánamo Bay, which currently holds 36 prisoners, is viewed by many human rights defenders as a final remnant of the policy of mass arbitrary detention.

The little light shed on these practices has largely been the result of hard and persistent work by international and civil society organizations, as well as lawyers who continue to sue states and other parties involved on behalf of victims and their families, some of whom are still detained.

A report presented earlier this year by Fionnuala Ní Aoláin, the U.N. Special Rapporteur on counterterrorism and human rights, following up on a 2010 U.N. report on secret detention, found that the “failure to address secret detention” has allowed similar practices to flourish in North-East Syria and Xinjiang Province in China.

How to deal with arbitrarily detained alleged ISIS (also known as Daesh) militia supporters and fighters in Syria and Iraq is an issue that goes back to the Obama era, but gained traction in 2018-2019, when ISIS lost its last major stronghold and significant territory, leading existing detention camps, like Al-Hawl, to swell in size. Al-Hawl was set up as an Iraqi refugee camp by the U.N. in 1991 with capacity for around 15,000 people. In 2018, it held around 10,000 Iraqi refugees. The majority of the 73,000-plus residents of this camp since 2019 are women and children, around 11,000 of whom are nationals of countries other than Syria or Iraq, living in poor shelter, hygiene and medical conditions.

All are detained by the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES) and the Syrian Defense Force (SDF), which are not state entities. Their efforts to investigate and prosecute possible ISIS fighters are still at the early stages, lack formal and widespread recognition and do not look at potential war crimes. With some prisoners detained for over six years, without charge, trial or formal identification, the situation is pretty much as it was in Afghanistan and Iraq.

According to Ní Aoláin, “No legal process of any kind has been established to justify the detention of these individuals. No public information exists on who precisely is being held in these camps, contrary to the requirements of the Geneva Conventions stipulating that detention records be kept that identify both the nationality of detainees and the legal basis of detention.”

She further states that, “These camps epitomize the normalization and expansion of secret detention practices in the two decades since the establishment of the detention facility at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba. The egregious nature of secret, incommunicado, harsh, degrading and unacceptable detention is now practised with impunity and the acquiescence of multiple States.”

In addition, around 10,000 men and 750 boys (of whom 2,000 and 150 are respectively not from Syria or Iraq) are held in some 14 detention centers in North-East Syria, accused of association with ISIS: “No judicial process has determined the legality or appropriateness of their detention. There are also reports of incommunicado detention.”

Efforts have been made, with varying success, to repatriate and release Iraqi refugees and Syrians internally displaced by the regional conflict: Around 2400 Iraqis have been repatriated over the past year or so.

European and other Western states were initially reluctant to repatriate their nationals — with former President Trump threatening to force them to — and some, such as the U.K., introducing measures to strip them of citizenship to prevent that. More recent efforts by European states have taken on a gendered approach, aimed at repatriating women and children in the camps. This approach, however, ignores the practice of the SDF to separate boys as young as 9 from their families and detain them, as a security risk, with men in prisons. Concern was only expressed during a prison break in early 2022 when it was feared these children would fall into ISIS’s hands, as though they were somehow safe with their original captors.

The gendered approach to repatriation of detainees plays into long-standing orientalist and imperialist views, framing Western powers as saviors of these women and children, whereas the men and boys left behind remain “ISIS fighters” without investigation and substantiation of this status.

In spite of the recent U.S. conviction of two former British ISIS fighters for their role in the kidnapping and deaths of Western hostages, the value of such a detention policy must be questioned. As in Afghanistan and Iraq, arbitrary detention and cruel punishment of hundreds of thousands of people, sometimes in conditions worse than those they are associated with, is unjustifiable.

Ní Aoláin’s report also found that no war on terror detainees have “received a complete and adequate legal remedy,” and the lack of due process has resulted in the continuing stigmatization and persecution of prisoners upon release from Guantánamo.

Two decades on, the absence of justice at Guantánamo remains a recurring theme. Prosecutors are now seeking a plea deal settlement with defense lawyers in the 9/11 case that would avoid trial — and thus torture revelations — and the death penalty, as the case continues to drag over a decade on.

The farce of “justice” is also amply demonstrated by the failure to release Majid Khan, who, following a plea bargain and several years of torture in secret CIA prisons, completed his sentence on March 1; the military jurors at his sentencing hearing decried the torture he faced and petitioned for clemency for him. However, he remains at Guantánamo as it is too unsafe for him to return to Pakistan and the U.S. has found no safe country for relocation. After being sued to take action, the U.S. Department of Justice has responded by opposing his habeas plea and claiming that he is still not subject to the Geneva Conventions.

The outcome of two decades of secret and arbitrary detention has been to deny justice to the victims of war crimes and terrorist acts, and create new victims — detainees and their families — who are also denied justice.

After two decades, the failure to close Guantánamo and end such secret and arbitrary detention and the secrecy that continues to surround them (such as the refusal to disclose the full 2014 Senate CIA torture report) are not errors or oversight but deliberate policy. It affords impunity for states and state-backed actors while tarring detainees with the “terrorist” label for the rest of their lives without due process, effectively leaving them in permanent legal limbo in many areas of everyday life.

A year after the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan, justice still evades the Afghan people. With the International Criminal Court (ICC) seeking to restart its investigation, but excluding the U.S. and its Afghan allies from its scope, effectively granting them impunity while focusing on the Taliban, “the ICC has so far come to represent selective and delayed justice to many victims of war in Afghanistan,” according to Shaharzad Akbar, former chair of the Afghanistan Independent Human Rights Commission. In addition, “a year after the withdrawal of international forces and many ‘lessons learned’ exercises, key troop contributing countries such as the United States, the U.K., and others in NATO are yet to reflect on the legacy of impunity they left behind.”

Addressing her report to the U.N. in April, Ní Aoláin stated, “It is precisely the lack of access, transparency, accountability and remedy that has enabled and sustained a permissive environment for contemporary large-scale detention and harm to individuals.”

Ní Aoláin expresses concerns in her report over the “lack of a globally agreed definition of terrorism and (violent) extremism, and […] the widespread failure to define acts of terrorism in concrete and precise ways in national legislation.” The vague definition has meant that any form of dissent and resistance against the state can effectively be labelled terrorist activity.

The focus on Guantánamo and mass detention of alleged terrorism suspects has drawn the attention away from the carceral practices of states. Torture, lengthy solitary confinement, rape, and other prisoner abuses in federal jails has not prompted the same criticism or action. The focus on ISIS prisoners also draws away attention from the mass detention and abuse of those incarcerated in Syrian prisons.

At the same time, mass arbitrary and secret detention of alleged terrorists has helped to justify the expansion of the prison-industrial complex, with the involvement of private contractors. Over the past two decades, the use of torture has grown worldwide. Perhaps most worrying has been the boom in the mass arbitrary detention and abuse of men, women and children worldwide without due process and few legal rights known as immigration detention, with the reframing of migration and asylum as a security issue over the past two decades.

That such reports and monitoring of the situation continue at the highest level and by civil society organizations means that the prisoners have not been obscured and forgotten or their situation normalized as much as the states involved would like them to be. The need for justice for all victims is on the path to any kind of peace, and thus it remains essential to keep pressing and supporting Ní Aoláin’s call for “access, transparency, accountability and remedy.”

This post was originally published on Latest – Truthout.

Since the prison at Guantánamo Bay opened in its “war on terror” iteration in 2002, there has been a tendency among liberal critics to hold it in stark relief to the “normal” civilian legal system. The cruelty and illegitimacy of Guantánamo Bay was contrasted against the inherent perceived legitimacy of U.S. courts and prisons. For as long as the detention center and the various tribunals have been around, it’s been common to hear arguments against them from human rights NGOs based on the efficacy and security of the civilian apparatus — the success rate of terrorism prosecutions, or the fact that no prisoner has ever escaped from a supermax prison.

There is no question that U.S. interrogators carried out unspeakable torture at Guantánamo Bay, that officials held prisoners incommunicado and without having been convicted of a crime, and operated for years with almost no oversight or visibility from outside watchdog groups. However, all of those elements are present to one degree or another in the normal incarceration regime in the United States, a point police and prison abolitionists have been making for the duration of the war on terror.

There has always been a fear that the abuses of Guantánamo Bay will migrate into the rest of the U.S. legal system. The reality is that many of them — including torture, indefinite pretrial detention and lack of oversight — have been there all along.

Ongoing plea negotiations in the 9/11 trial at Guantánamo Bay underscore just how outdated the conventional paradigm is. The five defendants in the trial are now in talks with prosecutors to bring the capital punishment case to close, but, according to The New York Times, one of the key requirements from the defendants in the prior round of negotiations in 2017 was that they be able to serve their sentences at Guantánamo, “where they are able to eat and pray in groups.” They were reportedly adamant that they didn’t want to be sent to the supermax prison in Florence, Colorado, where, as the Times writes, “federal inmates are held in solitary confinement up to 23 hours a day.” In the current round of negotiations, the Times reports that the five defendants want “guarantees that, even after their convictions, they would be able to eat and pray communally,” though they aren’t “pressing for a particular venue.” The ongoing fear that they could wind up back in extreme isolation, whether they’re held in military or civilian custody, reveals the baseline cruelty that permeates all U.S. prisons and detention facilities.

For prison abolitionists, the news that the five defendants are concerned about how they would be treated if transferred to a stateside prison is not surprising at all. “Finding that prisoners would reject transfer to a U.S. federal prison in Colorado in favor of remaining where they are in Guantánamo isn’t shocking. While we understand how egregiously torturous conditions at Guantánamo are, all prisons are deadly,” Woods Ervin, media director at Critical Resistance, an international prison abolitionist organization, told Truthout in an emailed statement. “We shouldn’t imagine that other prisons are ‘more gentle,’ especially under conditions of solitary confinement. Prisoners often push to remain under conditions where they can maintain their communities, collective practices, and shared fights for their freedom. The issue here is about prisoners making a collective, self-determined choice over the conditions they’re surviving under.” The conditions at the Florence supermax are horrific, even by U.S. standards. Incarcerated people describe cells made entirely of concrete, including the bed, where prisoners are kept isolated for 23 hours a day. Recreational time is an hour in a small cage. People there go for weeks, if not longer, without seeing the sky, or a highway, or any reminder at all of the outside world. It’s not hard to understand why the 9/11 defendants would want to condition any negotiation on avoiding that kind of treatment, either in a federal prison or post-conviction at Guantanamo Bay.

James Connell, an attorney for co-defendant Ammar al-Baluchi, confirmed the existence of the plea negotiations, which were first reported by The New York Times, in a statement posted to his defense team’s official Twitter account. “Negotiated agreements are part of all criminal cases, and negotiations have taken place throughout the case,” Connell said in the statement. “This process is not unusual: the vast majority of capital cases in the United States are resolved by plea.”

Alka Pradhan, a human rights lawyer who also represents al-Baluchi, said that the negotiations “represent one path to ending military commissions, stopping indefinite detention at Guantánamo Bay, and providing justice.” Military commissions are the novel legal apparatus in effect at Guantánamo Bay that combines military and civilian law. Connell and Pradhan declined to comment for this article.

The 9/11 trial at Guantánamo Bay is arguably in its most precarious state since the current iteration of the case began in 2012, when the five co-defendants were arraigned before a military judge. That judge, Col. James Pohl, is long gone, having retired before the case could advance beyond pretrial motions. Three judges have succeeded him, and an additional candidate had to recuse himself after being assigned the case but before he could sit on the bench.

The complications don’t stop there. The former chief prosecutor, Brig. Gen. Mark Martins, has also left the case, following clashes with the Biden administration about the applicability of international law at Guantánamo. Martins also served as the de facto chief spokesperson for the military commission system, which has been beleaguered by complications since Congress first created it in 2006, and updated in 2009. For nearly a decade, the defense and prosecution have argued about the rules of that system — from the mechanics of compelling witnesses to a remote military base on occupied, foreign soil, to the applicability of the Bill of Rights in the proceedings. The admissibility of evidence derived from torture has been central to the hearings, and remains unresolved.

The COVID pandemic also essentially shut down the entire trial for 500 days.

There are still 38 men held at Guantánamo Bay, 10 of whom have been charged in the military commissions system. Of the remaining prisoners, 19 have been cleared for transfer to a third-party country if security conditions are met. Seven have not been charged with a crime, but also aren’t cleared for transfer — this group is often referred to as “forever prisoners.” Two have been convicted, including Majid Khan, who also took a plea. Khan was tortured in the same CIA program as Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, who is accused of being the 9/11 “mastermind.” Last year, a military jury — known as a panel — urged leniency in sentencing Khan, who was the first victim of CIA torture to describe his treatment in a courtroom. The top sentencing official, known as the Convening Authority, approved a 10-year sentence and applied time served, meaning his term was finished on March 1 of this year. That doesn’t mean he’s free to go, however. The U.S. government reserves the right to continue to detain Guantánamo prisoners even after their time is served if a suitable third-party country hasn’t been identified. Khan’s lawyers are now calling for him to be transferred without delay.

The response from the military panel to Khan’s treatment underlines the complications of bringing the 9/11 case to trial. Each of the defendants in that case was tortured by the CIA, including waterboarding, rape and sexual threats, and repeated physical and psychological abuse. Recently disclosed legal filings revealed that Ammar al-Baluchi was used as a training tool: His torture was “on-the-job practice” for other interrogators. If the Khan case is any indicator, that kind of treatment would heavily mitigate against a death penalty sentence, even in a case as notorious as the 9/11 trial.

For as much reasonable worry as there is about Guantánamo Bay policies seeping into the civilian system, at least some of the torture enacted at Guantánamo in the early days of the war on terror was exported from U.S. prisons. Charles Graner, one of the few U.S. army soldiers held accountable for torture committed at Abu Ghraib in Iraq, “cut his teeth as first a guard / lieutenant at Pennsylvania’s max-security state prison, SCI-Greene,” Robert Saleem Holbrook, executive director of the Abolitionist Law Center, told Truthout in an emailed statement. “It was here that Graner routinely abused prisoners who were ‘in the hole’ (solitary confinement), just before he was activated for the reserves and sent to Iraq. I was on a unit (confined in solitary) with him [Graner].”

“This is just one example of how the U.S.’s domestic torture within its solitary confinement units [is] exported as part of its so-called war on terror,” Saleem Holbrook added.

Much of the abuse and torture the U.S. government has carried out in the wars it has waged since 2001 have been forgotten, ignored or justified. The image rehabilitation attempts of George W. Bush, Dick Cheney, and others responsible for creating the torture and kidnapping programs are proof of that. But much of the abuse that happens inside prison walls is ignored as well, made deliberately invisible to perpetuate an unjust system of social control. The ongoing plea negotiations in the 9/11 case are the most recent example of how blurred the lines between these systems are, and that it’s never clear that the damaging influence only travels one way. Those seeking to find justice by closing the prison at Guantánamo Bay should also ask whether justice is possible so long as any prison exists in the United States.

This post was originally published on Latest – Truthout.

To begin our coverage of day two of the historic nomination hearings for Supreme Court nominee Ketanji Brown Jackson, we discuss the attacks by Republicans on her work defending suspects at Guantánamo Bay prison. Given that Jackson was one of hundreds of legal professionals in a project that exposed the lies and brutality undergirding Guantánamo, “to criticize her work in that project is nonsensical to me,” says Baher Azmy, legal director of the Center of Constitutional Rights, who has represented people held at Guantánamo and defended their rights. “Her work should be valorized.”

This is a rush transcript. Copy may not be in its final form.

AMY GOODMAN: President Biden’s Supreme Court nominee Ketanji Brown Jackson faced a marathon day of questions from members of the Senate Judiciary Committee Tuesday. She’s set to make history if she becomes the first Black woman and first public defender to serve on the nation’s highest court. Judge Jackson faced a variety of attacks from Republican senators. We’re going to begin by looking at the focus on her work as a federal public defender who represented people detained at Guantánamo. This is Judge Jackson talking about representing Guantánamo prisoners.

JUDGE KETANJI BROWN JACKSON: After 9/11, there were also lawyers who recognized that our nation’s values were under attack, that we couldn’t let the terrorists win by changing who we were fundamentally. And what that meant was that the people who were being accused by our government of having engaged in actions related to this, under our constitutional scheme, were entitled to representation, were entitled to be treated fairly. That’s what makes our system the best in the world. That’s what makes us exemplary.

I was in the Federal Public Defender’s Office when the Supreme Court — excuse me, right after the Supreme Court decided that individuals who were detained at Guantánamo Bay by the president could seek review of their detention. And those cases started coming in. And federal public defenders don’t get to pick their clients; they have to represent whoever comes in, and it’s a service. That’s what you do as a federal public defender: You are standing up for the constitutional value of representation.

AMY GOODMAN: Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson was later grilled by Republican Senator Lindsey Graham about her time representing people detained at Guantánamo. This is part of their exchange.

SEN. LINDSEY GRAHAM: So, as you rightfully are proud of your service as a public defender, and you represented Gitmo detainees, which is part of our system, I want you to understand, and the nation to understand, what’s been happening at Gitmo. What’s the recidivism rate at Gitmo?

JUDGE KETANJI BROWN JACKSON: Senator, I’m not aware.

SEN. LINDSEY GRAHAM: It’s 31%. How does that strike you?

JUDGE KETANJI BROWN JACKSON: Any —

SEN. LINDSEY GRAHAM: Is that high, low, about right?

JUDGE KETANJI BROWN JACKSON: I don’t know how it strikes me overall.

SEN. LINDSEY GRAHAM: You know how it strikes me? It strikes me as terrible.

JUDGE KETANJI BROWN JACKSON: Yes, that’s what I was going to say.

SEN. LINDSEY GRAHAM: OK, good. We found common ground. Of the 229 detainees released from Gitmo — of 729 released, 229 have gone back to the fight. … Would you say that our system in terms of releasing people needs to be relooked at?

JUDGE KETANJI BROWN JACKSON: Senator, what I’d say is that that’s not a job for the courts in this way, that —

SEN. LINDSEY GRAHAM: As an American, does that bother you?

JUDGE KETANJI BROWN JACKSON: Well, obviously, Senator, any repeated criminal behavior or repeated attacks, acts of war bother me as an American.

SEN. LINDSEY GRAHAM: Yeah, well, it bothers me.

AMY GOODMAN: After this exchange, Republican Senator John Cornyn used his time to try to accuse Judge Jackson of calling former President George W. Bush and former Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld war criminals in a court filing.

SEN. JOHN CORNYN: Talking about when you were representing a member of the Taliban, and the Department of Defense identified him as an intelligence officer for the Taliban, and you referred to the secretary of defense and the sitting president of the United States as war criminals. Why would you do something like that? It seems so out of character.

JUDGE KETANJI BROWN JACKSON: Well, Senator, I don’t remember that particular reference in — I was representing my clients and making arguments. I’d have to take a look at what you meant. I did not intend to disparage the president or the secretary of defense.

AMY GOODMAN: In a minute, we’ll look at other topics raised in Tuesday’s confirmation hearings for President Biden’s Supreme Court nominee, Ketanji Brown Jackson, like sentencing in child pornography cases, issues of abortion and other issues, but we’re going to begin with these points on Guantánamo as we’re joined by Baher Azmy — he’s legal director of the Center of Constitutional Rights, where for the past two decades he’s been part of the legal team challenging the U.S. government over the rights of Guantánamo detainees — and Alexis Hoag, who’s a professor of law at Brooklyn Law School and a former federal public defender. And we’re going to talk about the significance of Ketanji Brown Jackson being a former public defender.

But we’re going to start with Baher Azmy on the content of the accusations. Can you talk about the judge’s record on these Guantánamo cases and the allegations made by both Cornyn and Lindsey Graham?

BAHER AZMY: Sure. Thank you, Amy.

So, Judge Jackson was one of many hundreds of lawyers who joined a project to challenge this remarkable authoritarian experiment in Guantánamo that purported to — that actually held exclusively Muslim prisoners in an island, without any protections of law, where they were subject to persistent torture and arbitrary detention based on the executive say-so. So, to sort of criticize her work in that project is nonsensical to me. She’s operating in the highest traditions of the law. And it’s lawyers in the legal project that exposed so many of the underlying lies in Guantánamo, lies about dangerousness, lies about humane treatment, lies about national security and compliance with law. So, her work should be valorized.

You know, in terms of — you know, Lindsey Graham is, like, living in a post-9/11 fever dream where he continually wants to fight these old battles. The 31% recidivism number is this made-up Soviet-style number designed to mask, again, fundamental lies about Guantánamo. The overwhelming majority have absolutely nothing to do with initiating any fighting, let alone returning to the battlefield. And, you know, it’s just sort of perpetuating this mythology that men there were dangerous. In our overwhelming experience, men who left Guantánamo left as the project was designed to do: left them broken, not angry.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And, Baher, I’d like to follow up on that, on this whole issue of the recidivism rate Lindsey Graham mentioned. First of all, as you allude to, most of the people in Guantánamo had never been — or, none had been convicted, or very few were actually convicted of a crime, so that even the issue of recidivism, when a person has not been convicted, is suspect. But also, even if you take Lindsey Graham’s number of 31%, I looked up what the recidivism rate is in the United States for prisoners in general, and two-thirds of people who serve in U.S. prisons are arrested again within three years, and three-quarters within nine years. So, the, quote, “recidivism rate” of people in the United States is far worse than even what Lindsey Graham is saying about these prisoners.

BAHER AZMY: Yes. This is really a made-up number. It’s garbage in, garbage out, like most of the Guantánamo project. You’re right. It starts with an assumption that people committed a crime to begin with. There was no — there were no criminal convictions. That’s the data we should be focusing on. And under the government’s own statistics, only 8% — evidence, only 8% were ever accused of being members of al-Qaeda or the Taliban, as we all, I hope, know by now. The overwhelming majority were picked up as a result of bounties and shipped to Guantánamo, where — officials later secretly recognized, and lawyers ultimately exposed, had absolutely nothing to do with terrorism. And this 31% number, it’s really — it’s preposterous on its own terms. It includes individuals — this particular number includes individuals who — for example, Uyghurs — were released and spoke to The New York Times. That’s the notion of returning to the fight that this number captures. Under our analysis, at most, there have been 12 who have done — a dozen or so who have actually sort of engaged in any sort of combatant activities after being released, out of 779.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And could you talk about the essential facts to understand about Judge Jackson’s work on Guantánamo cases?

BAHER AZMY: Yeah. So, she is one of many hundreds of individuals, from sort of every thread of the legal profession — federal public defenders; big corporate law firms; NGOs, like my organization, the Center for Constitutional Rights, which was responsible for coordinating a lot of these legal efforts; academics; and, ultimately, a global movement — to challenge this profoundly extraconstitutional project of arbitrary detention and abuse there. And what she was doing by representing individual detainees was challenging the executive branch to ensure that any kind of detention of human beings is done pursuant to law and not just executive fiat. And in so doing, she was part of a really — a project that exposed so many of the lies and brutality undergirding Guantánamo. And I think that’s an obviously useful perspective that connects the law to the lived experience of individuals who are harmed by the law. And I hope that will be a useful perspective on the court.

AMY GOODMAN: And the specific people that she represented, the four people, have since been released. Also, this issue that Cornyn said she called them war criminals, she actually didn’t use that word. In the brief — and I’m looking — there are number of pieces on this, this one in The New York Times: “The petitions each named Mr. Bush and Mr. Rumsfeld — along with two senior military officers who oversaw the Guantánamo detention operation — in their official capacities as respondents. And, they said, such officials’ acts in ordering or condoning the alleged torture and other inhumane treatment of the detainees ‘constitute war crimes and/or crimes against humanity in violation of the law of nations under the Alien Tort Statute.’” If you could end with that, Baher Azmy, the accusations against Bush and Rumsfeld and the government for how prisoners were treated?

BAHER AZMY: Yeah. So, in her petition, she alleged what we know to be true, that individuals detained in Guantánamo were subject to torture. And what follows from that, under well-established international law, including international law [inaudible] was responsible for promulgating, particularly after Nuremberg, those constitute war crimes. So, it’s a bit of a sort of fallacious gotcha in the hearing to say she sort of literally accused them of war crimes. But I want to be clear: Donald Rumsfeld is credibly accused of war crimes, and he’s never been held accountable for that, although we brought a case in German courts accusing him of war crimes in Guantánamo and elsewhere. And as we, you know, focus on the devastation and destruction in Ukraine, it’s worth remembering the onslaught of devastation and destruction brought by Bush and Rumsfeld in Iraq, Afghanistan and elsewhere.

AMY GOODMAN: Baher Azmy is legal director of the Center of Constitutional Rights.

This post was originally published on Latest – Truthout.

On the 20th anniversary of Guantanamo Bay Kasmira Jefford of Geneva Solutions looks at the legacy of the so-called “war on terror”. She does so in conversation with UN special rapporteur Fionnuala Ní Aoláin on the promotion and protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms while countering terrorism. From camps in north-eastern Syria, where thousands are detained without legal processes, to China where detention camps are posing under the guise of “education facilities” – secret detentions and enforced disappearances are still happening every day under the banner countering terrorism. Here some lengthy extracts:

In 2010, UN experts from four different working groups and special procedures joined forces to produce one of the most comprehensive studies to date on widespread systematic torture, enforced disappearances, arbitrary detention and secret detentions taking place across the world and condemning the wide range of human rights violations committed by countries.

In a follow-up report presented on Wednesday at the Human Rights Council 49th session, the special rapporteur said 10 years on, these practices are still rife and deplored the “abject failure” by states to implement the recommendations of the 2010 study.

GS News: In 2010, UN experts published a milestone study on secret detentions. What does your follow-up report show?

Fionnuala Ni Aolain: The 2010 report was unusual because it involved… four special procedure mechanisms coming together and identifying each in their collective way the scale of the problem of systematic torture and rendition of persons across borders, and systematic disappearances, arbitrary detention, and secret detentions. The [follow-up] report we’ve just published does a stock-taking and assesses whether or not the recommendations of the special experts were implemented. And possibly the single most depressing thing about that review is that the annex lists every single person who was named in the 2010 report – hundreds of names who were rendered, tortured, or both – and not a single individual received an adequate remedy [for the violation of human rights they experiend]. There was no accountability, no person was ever charged with crime for any of those acts.

The second part of the follow up report focuses on what that culture of impunity enabled. And what I find is that the culture of impunity, fostered and enabled by the “war on terror” as it was called essentially has created and enabled the conditions in which other places of mass detention have emerged. The report focuses on two of them : Xinjiang, China, and the situation in [in detention camps] in northeast Syria.

One of the observations you make is that ‘secret’ detention has evolved in the past two decades to encompass more complex forms of “formally lawful” or legalised transfer. Can you explain?

In the evolution that we’ve seen…dark-of-night arrivals into places like Poland and Lithuania and other countries that were accepting these rendition flights stopped because the global heat, if you want, on that kind of rendition was simply too high. It just became intolerable and unacceptable for states who were cooperating in enabling torture and rendition to continue to do it. But there’s been this transition into this ‘lawful transfer’. These are diplomatic assurances, [for example], where one state offers an assurance to another state that they will not torture the person who’s transferred into their custody.

But as the report makes clear, if you have to provide an assurance that you’re not going to do that, it tells you that there’s something fundamentally dysfunctional about the legal system that’s producing the assurance – and there’s a fundamental question about the trustworthiness of the assurance if it happens. And what we know in practice is that so many of those assurances are not worth the paper they are written on. People have had the worst kinds of practices meted out to them under the cover of diplomatic assurance. And there have been no consequences for states in breaking those assurances.

One of the issues you raise in the report is the lack of a globally agreed definition on terrorism or acts of terrorism. Why has it been so complex to agree upon a definition?

Part of what happened is that 9/11 spawned this culture where everybody agree that terrorism was a bad thing but nobody ever defined it. …What we see in practice is the systemic abuse of counterterrorism across the globe. We see it in multiple countries. Over 67 per cent of all the communications the mandate has sent since 2005 have involved the use of a counterterrorism measure against a civil society actor. So this tells you that actually, they’re doing really bad counterterrorism.

We have to understand that, in fact, there’s a structural endemic problem. And in many countries, states’ security is governed by counterterrorism. The example I often use is the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, when women’s rights activist Loujain al-Hathloul was jailed on terrorism charges and processed through a Special Criminal Court. So this shows terrorism being everything and nothing.

…….

In your annual report presented to the General Assembly in October last year, you said that efforts to improve counter terrorism measures are in fact damaging human rights. Would you say that counterterrorism is incompatible with the respect of human rights?

Security is a human right. It’s found in the Universal Declaration on Human Rights. Our most fundamental right that enables us to have other rights is the right to be secure. So I don’t think they’re incompatible and I don’t think the drafters of the Universal Declaration thought they were incompatible. I grew up in Northern Ireland in a society which was, in many ways, defined for decades by counterterrorism law. The problem is that expansive counterterrorism law, which is what we have, is imprecise – and vague counterterrorism law is fundamentally incompatible with the rule of law.

The fundamental idea contained in the rule of law is that if you are to be charged with an offence by the state, that you know precisely what acts you engaged in that are likely to make you subject to the course of power of the state. And the fundamental problem with terrorism is that it really, in so many countries, kind of injures that the concept of the rule of law, because it’s not precise. A reasonable individual could not know what kind of actions they would engage in would implicate the use of a state or measure against them. So I don’t think it’s incompatible but unfortunately, we have very few examples of good practice.

One of the key examples you highlight in your report are the camps in northeast Syria where thousands of people – the majority women and children – are being detained. You describe this as “a human rights black hole”. What can or should be done immediately for these people who are living in desperate situations?

You have thousands, almost over 60,000 men and women being held in detention centres, prisons, who have never been through any legal process; the idea that we would hold people in these conditions is simply abhorrent. And then we turn to look at the conditions in those camps. The special rapporteur on torture and I have found that the conditions in the camps reach the threshold of torture, inhumane, and degrading treatment under international law. So the fact that they are there is also unacceptable. But the bottom line is that we have states, mostly western states, who simply will not take back their nationals including children, who refuse.

So, there’s a large-scale political solution that’s required to fix the challenge in northeast Syria, which involves all of the significant parties to the conflict. However, in the short run, the only international law compliance solution to the situation in these camps is the return of women and children to their countries of nationality. We have some states who have made active and ongoing efforts to do so and some who have made no effort.

…

This post was originally published on Hans Thoolen on Human Rights Defenders and their awards.

Abu Zubaydah, whom the CIA once mistakenly alleged was a top al-Qaeda leader, was waterboarded 80+ times, subjected to assault in the form of forced rectal exams, and exposed to live burials in coffins for hundreds of hours. Zubaydah sobbed, twitched and hyperventilated. During one waterboarding session, he became completely unresponsive, with bubbles coming out of his mouth. “He became so compliant that he would prepare for waterboarding at the snap of a finger,” Neil Gorsuch wrote in his 30-page dissent in United States v. Zubaydah.

On March 3, in a 6-3 decision, the Supreme Court dismissed Zubaydah’s petition requesting the testimony of psychologists James Mitchell and John Jessen, whom the CIA hired to orchestrate his torture at a secret CIA prison (“CIA black site”) in Poland from December 2002 until September 2003. Zubaydah was transferred to other CIA black sites before being sent to Guantánamo in 2006, where he remains today with no charges against him.

Zubaydah sought information: (1) to confirm that the CIA black site in question was located in Poland; (2) about his torture there; and (3) about the involvement of Polish officials. First the Trump administration — now the Biden administration — claim that confirming the location of the CIA black site in Poland is a “state secret” that would significantly harm U.S. national security interests. Zubaydah needs Mitchell and Jessen’s testimony to document his treatment from December 2002 to 2003 at the CIA black site in Poland for use in the ongoing Polish criminal investigation of Poles complicit in his torture. Those details have not been publicly documented.

Former CIA Director Mike Pompeo wrote in a declaration that although the enhanced interrogation techniques are no longer classified, the location of the CIA black site in question remains a state secret. Pompeo maintained that soliciting information about the involvement of Polish nationals in Zubaydah’s treatment could compromise national security.

But the location of the Polish CIA black site has been publicly acknowledged in several venues. The 683-page report of the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, published in 2014, detailed the CIA detention and interrogation program, including details about Zubaydah’s torture prior to being sent to the CIA’s black site in Poland. In 2007, the Council of Europe issued a long report that found Zubaydah was held at the Polish CIA black site after his capture in 2002. The former president of Poland told reporters in 2012 that the CIA black site in Poland was established with his knowledge. In 2014, the European Court of Human Rights concluded beyond reasonable doubt that Zubaydah was held in Poland from December 2002 to September 2003.

Moreover, in 2017, the U.S. government allowed Mitchell and Jessen to testify about how they developed the idea of waterboarding, that they asked the CIA to stop using “enhanced interrogation techniques” (aka torture) on Zubaydah, and how the CIA leadership refused. Once again, in 2020, the U.S. government permitted the two psychologists to testify at military commission hearings at Guantánamo about how Zubaydah was waterboarded and kept awake for 120 consecutive hours.

Zubaydah’s attorneys sought to elicit information about Zubaydah’s conditions of confinement and the details of his treatment without risk to any state secrets. They asked that the two psychologists be allowed to testify without confirming the location of the black site or the cooperation of foreign nationals. They offered to use code words to avoid specific reference to Poland or the involvement of Polish officials.

“The Polish prosecutor already has information [that it happened in Poland] and doesn’t need U.S. discovery on the topic,” David Klein, Zubaydah’s attorney, told the court during oral argument. “What he does need to know is what happened inside Abu Zubaydah’s cell between December 2002 and September 2003. So I want to ask simple questions like, how was Abu Zubaydah fed? What was his medical condition? What was his cell like? And, yes, was he tortured?”

The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals held that the state secrets privilege did not apply to information already publicly known, and since Mitchell and Jensen are private parties, their disclosures would not be attributed to the U.S. government. But the Supreme Court disagreed and reversed the Ninth Circuit’s decision, deferring to Pompeo’s spurious national security claims.

Stephen Breyer (whose less-than-liberal voting record I documented in my February 5 Truthout article) wrote the plurality opinion, joined by five of his right-wing colleagues on the court. Gorsuch filed a scathing dissent on behalf of himself and Sonia Sotomayor. Elena Kagan agreed with the dissent that Zubaydah’s petition should not be dismissed, but she disagreed with the dissent’s reasoning.

Even though it was widely known that the site where Zubaydah was tortured was located in Poland, the court’s plurality agreed with the Biden administration and held that allowing Mitchell and Jessen to testify at a criminal proceeding in Poland would officially reveal a state secret — i.e., the location of the CIA black site in Poland — that could harm national security.

“[A] court should exercise its traditional ‘reluctan[ce] to intrude upon the authority of the Executive in military and national security affairs,”’ Breyer wrote. He cited Pompeo’s claim that “sensitive” relationships with other countries are “based on mutual trust that the classified existence and nature of the relationship will not be disclosed.”

The plurality rejected the Ninth Circuit’s conclusion that since Mitchell and Jensen are private parties, their disclosures did not amount to the U.S. confirming or denying anything. Because the psychologists “worked directly for the CIA as contractors,” created and implemented the enhanced interrogation program, and personally interrogated Zubaydah, their confirmation or denial “would be tantamount to a disclosure from the CIA itself,” Breyer concluded.

Thus, the court held, Zubaydah cannot secure the testimony of Mitchell and Jensen about any of his three requested categories of inquiry, including the details of Zubaydah’s torture during the period in question.

“Nothing in the record of this case suggests that requiring the government to acknowledge what the world already knows to be true would invite a reasonable danger of additional harm to national security,” Gorsuch wrote in dissent. He noted that the government has the burden to prove it is entitled to assert the state secrets privilege, and it has failed to carry that burden.

Decrying the court’s failure to even probe the government’s privilege claim at all, Gorsuch observed, “We have replaced independent inquiry with a rubber stamp.”

“The Constitution did not create a President in the King’s image but envisioned an executive regularly checked and balanced by other authorities,” Gorsuch declared. He cited the executive branch’s over-classification of documents and cautioned the court against “abdicating any pretense of an independent judicial inquiry into the propriety of a claim of privilege and extending instead ‘utmost deference’ to the Executive’s mere assertion of one.”

The dissent accused the government of seeking dismissal of Zubaydah’s petition to avoid “further embarrassment for past misdeeds.” Gorsuch noted that “our government treated Zubaydah brutally — more than 80 waterboarding sessions, hundreds of hours of live burial, and what it calls ‘rectal rehydration.’”

Indeed, as Zubaydah’s attorney Joseph Margulies said in 2016, Abu Zubaydah is “the poster child for the torture program, and that’s why they never want him to be heard from again.”

Gorsuch concluded his dissent by writing, “But as embarrassing as these facts may be, there is no state secret here. This Court’s duty is to the rule of law and the search for truth. We should not let shame obscure our vision.”

No one responsible for the crimes at Guantánamo has been tried for the ‘systematic use of torture’, as human rights experts have noted. Yet the co-founder and publisher of WikiLeaks, Julian Assange, sits in Belmarsh Prison, Britain’s Guantánamo. The US seeks to extradite him to face charges of espionage. Who is Julian Assange and why is the US so desperate for his extradition?