Janine Jackson interviewed the Center for Constitutional Rights’ Pardiss Kebriaei about Guantánamo prisoners for the January 14, 2022, episode of CounterSpin. This is a lightly edited transcript.

AP via Buffalo News (1/10/22)

Janine Jackson: On January 10, Associated Press’ “Today in History” feature highlighted January 10, 2002, when, it said, “Marines began flying hundreds of Al Qaeda prisoners in Afghanistan to a US base in Guantánamo Bay, Cuba.”

Twenty years on from the opening of that monument to the lawlessness and cruelty and racism of the US after September 11, 2001, and media are still shorthanding Guantánamo detainees as Al Qaeda prisoners.

A bigger problem is US news media’s erratic attention to the continued operation of a military prison specifically designed to be beyond the reach of US law, holding only Muslim men and boys, most of whom were never charged with anything, much less convicted.

Even after the official end of the war on Afghanistan, the sense one gets of Guantánamo from the press is that it’s lamentable, yet somehow unchangeable. Outrageous, yet somehow acceptable.

Keeping it out of the US public sight and mind was part of government’s plan for Guantánamo. Some people have been resisting that effort along with defending detainees’ rights for many years now, including our guest. Pardiss Kebriaei is senior staff attorney at the Center for Constitutional Rights and a fellow at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study. She joins us now by phone. Welcome back to CounterSpin, Pardiss Kebriaei.

Pardiss Kebriaei: Thank you so much, Janine.

JJ: Around January 11, the official 20-year mark, people may have seen headlines that a US government review panel has approved the release of five men from Guantánamo. That sounds like motion, like movement. Many people, I think, may not understand the tremendous, maybe unbridgeable, gulf between “approved for release” and leaving Guantánamo.

PK: It is a very good thing that those men have been cleared. They should have been cleared, or probably could have been cleared, years ago. But under the Trump administration, for four years, there was just very little movement of any kind on Guantánamo. So things are finally picking up again this year under the Biden administration.

But yes, there’s a very big distance between being approved for transfer, which means basically that every government agency with a stake in these detentions has looked at its case files on these men, heard from them, and determined that their detention is not necessary. That’s significant, obviously. But there have been men who were cleared for release years ago under the Obama administration who are still sitting in Guantánamo.

So yeah, the work right now is to transfer those men out, for the government to find countries for them to be sent to, either send them home–and in some cases they can be sent home–or to find third resettlement countries for them, and then to continue this process, which is underway, of approving for transfer the men who remain.

At this point, 20 years on from 9/11, those processes shouldn’t really be necessary. A certain number of detainees at Guantánamo, the majority, who have never been charged and will never be charged by the government: The government has had 20 years to determine whether it’s going to bring charges against them, and it has not. So more than half of the men at Guantánamo are in that category. Administrative review processes really at this point should not be necessary for the government to decide, to determine, that continuing detention into year 21, 22 and on is not necessary. But that is the process it’s undertaking, and it just needs to continue it and finish it, and begin the work of transferring men out now. It is, as you said, and as I’ve said, 20 years, two decades, of detention, and it needs to end.

JJ: Just for clarity, these men have to be transferred to other countries. It seems to me, if you just think about it, people who’ve been held without charge for decades now have been declared not to be a threat; why are we still in charge of where they live afterwards? What are these rules that govern where they can go, and why can’t they come to the US?

PK: By law, there’s a ban on transferring them to certain countries, and certainly to bringing them to the United States for any reason, even for prosecution. So there are legal obstacles that the United States Congress has erected to where they can go.

But despite those obstacles–I mean, those have existed for a long time, and transfers have happened by the dozens before; today we’re talking about a very small number of people who remain at Guantánamo. It’s actually, for as many ways as we can lament the fact that it still exists, I’ve been reflecting on how remarkable it actually is where we are, which is from a population of nearly 800 in the early 2000s, in the early years of the prison, to 39 men today.

That’s remarkable, and that’s the work of pressure, the work of organizers, journalists, advocates, lawyers, the men themselves, really, in surviving this long. I mean, it’s not the usual trajectory for prisons to empty, and it has.

So today we’re talking about a very small number of people. And, again, nearly half of whom have been approved for transfer by the United States itself. So this is not at this point insurmountable work. It can be done. Third countries need to be found in many cases, or people can just be repatriated. But that’s work that has happened before, and can happen again. Today I think it’s just a matter of, as usual, a bit of politics and will, and whether and how to make this a real priority for the Biden administration, admittedly in the middle of a lot of crisis.

JJ: Right.

PK: Right, I mean, there is context here, and I think everyone understands that. But that can’t continue to delay the work of finally shutting the prison down. It can be done, and it needs to happen. Twenty years is enough. It’s been enough for a long time.

JJ: Is there a real disagreement? Because we see some finger-pointing that Congress is what’s holding it up, that if Biden would just act, something could happen. What is behind the inertia, or who really does have the power? Does it require a multipart effort?

PK: No, it really doesn’t, I think. This is work that can reside in the Biden administration. It’s largely the work of quickly continuing to approve people for transfer, if that’s the process the administration feels it needs to undertake. Although lawyers have said for a long time that at this point, 20 years on, for the men the government has never charged and has no intention of charging, it really needs no further process.

JJ: Right.

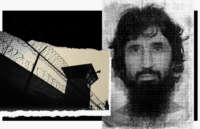

Pardiss Kebriaei: “There’s wide acknowledgement and understanding that now is the time to finally finish the work of closing the prison.” (image: Witness to Guantánamo)

PK: It sort of speaks for itself that they remain uncharged and in this category for 20 years. But anyway, for the government to complete its review process, if that’s what it’s doing, and to find third countries, or to repatriate the people that it is clearing, that’s work that can happen by the administration, by the State Department.

I think the reason it has not, frankly, is a matter of getting their bearings internally and a lot of crisis and chaos that I think the Biden administration inherited. But I think there’s wide acknowledgement and understanding that now is the time to finally finish the work of closing the prison, and that it can be done; it’s just a matter of doing it.

And there are right now 18 men who are sitting in Guantánamo, have been there for decades, and are approved for transfer, third countries can be found for those men, need to be found for those men. There are countries the government sent people to by the dozens under the Obama administration. There were dozens of people sent to Oman, to Saudi Arabia, to other countries in the past, and the same can be done. It doesn’t necessarily have to be a matter of finding individual placements for every single person.

That said, I think that one lesson of transfers in the past is that real care needs to be taken, also, with where people are resettled and the conditions in which they land and the support they have. These are people who have been treated brutally in all the ways that we know and have been documented, and need real support in order to recover, I don’t know, but just to reintegrate. So care needs to be taken.

But it can be done. The government has transferred dozens of people to countries before, and the same can be done now. So it’s really just work that can largely reside in the administration, in the Biden administration, and it’s just a matter of doing it now.

JJ: We may, if that action is taken, we’ll be hearing at some point about the lesson, about what we learned from Guantánamo, about what it meant. And I think many listeners, particularly younger listeners, may not have a real sense of the unprecedented nature, and just the science fiction-y nature, of Guantánamo. So if we could just return, briefly, to that first principle, the fact that it was put not on US soil, not just to kind of keep reporters from being too inclined to investigate it–the hurdles for journalists have always been high–but there was an idea that if the US was holding foreigners outside of the US, that US courts couldn’t do anything about it. When we talk about this aura of lawlessness, that was built-in and intentional.

PK: That’s right. It is true that there have been a lot of things about Guantánamo that are particular: the remote nature of it, the really overt way that in the beginning the Bush administration denied people any even theoretical rights, the really overt kinds of torture that happened and were talked about in terms of methods. So there are certainly things that were very overt and brutal and particular to Guantánamo and, at the same time, I think anyone who has been exposed to or in or touched the criminal legal system in the United States, or prison in the United States, knows torture is not unique to Guantánamo, prolonged detention is not unique to Guantánamo, the lack of due process is not unique to Guantánamo.

And so I’ve sort of resisted–and a lot of us doing this work, advocates, lawyers alike, have resisted–this notion that Guantánamo is exceptional. I think what has made it exceptional is the way that all these things that we do in the United States, by the thousands and the millions and historically, came together in this particular way, in this particular prison and in this particular time against this group of people.

So I like to say it is very particular, but not exceptional. And that doesn’t take away at all from the brutality of what people have been through, and the harm of it, and that it is as wrong and depraved at Guantánamo as it is in prisons in the United States. And I think that’s not a new idea. I think there have been a lot of us organizers and advocates, like I was saying, who understand that now, and who have the broader context for the way that we treat and punish people we deem to be threats in some form.

But we can hold both, to say that it isn’t exceptional and it’s depraved and it needs to end and it matters. It doesn’t matter more than the imprisonment of a client I have in the United States who’s serving a life without parole sentence in Pennsylvania State Prison. But it matters as well. It’s and, not but.

JJ: Yeah. And finally, as with the deeper problems with the criminal legal system in this country, it seems sometimes to be missed in reporting that Guantánamo harmed and harms not only the people trapped there, but the system within it operates, the rule of law. If those things aren’t jokes to us, then this is a concern for everyone, and not simply a story about some hundreds of unfortunate men.

Sharqawi Al Hajj

PK: Absolutely. And I’ve reflected on this more recently, just the circles of harm. And it harms us in terms of law and democracy and human rights and all of that, and I don’t mean to sort of be dismissive about those things; those matter. But on a human level, there are circles of harm around this prison, as there are around every prison in America.

I think about the men that I have met and represent, a man who’s still there 20 years on, his name is Sharqawi Al Hajj, he’s 47 and he’s from Yemen. We could talk about the particular cruelty of his experience in Guantánamo today, not knowing, still not knowing, whether and when he might be released, or if he’s going to die there. So there’s something, like I said, very particular about the indefinite nature of detention.

But it’s not just him. It’s his family, it’s that circle of people. It’s people at Guantánamo, the staff, the guards who’ve had to guard the prison, and the medical staff who’ve had to follow orders to force-feed hunger-striking detainees, and advocates who have traveled down to the base for years and had to sit across from people who’ve suffered torture. There are reverberations of all these things and, so yes, it’s more than just the individual inside. There’s a whole world of people on the outside who are affected, and carry the pain and trauma of Guantánamo, and that’s part of why it’s so important to remove these sites from the landscape.

JJ: We’ve been speaking with Pardiss Kebriaei, a fellow at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study and senior staff attorney at the Center for Constitutional Rights. You can follow their work online at CCRJustice.org. Pardiss Kebriaei, thank you so much for joining us this week on CounterSpin.

PK: Thank you so much for having me, Janine.

The post ‘It’s 20 Years of Detention and It Needs to End’ appeared first on FAIR.

This post was originally published on FAIR.

— by definition — keeps the vast majority of its residents in a state of deep distress and high anxiety.

— by definition — keeps the vast majority of its residents in a state of deep distress and high anxiety.