This content originally appeared on Vincent Moon / Petites Planètes and was authored by Vincent Moon / Petites Planètes.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Vincent Moon / Petites Planètes and was authored by Vincent Moon / Petites Planètes.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

In August 2014, I helped organise a national seminar in Magelang, Central Java, that celebrated the 200th anniversary of the supposed “discovery” of the temple of Borobudur by the then British lieutenant governor-general of Java, Sir Stamford Raffles. Archaeologists, historians, and conservation experts convened to discuss what could be done to preserve Borobudur for another 200 years. Later that year, and still in the spirit of this celebration, the Indonesian Postal Service issued 20,000 unique postage stamps showing the Borobudur temple foregrounded by a painted portrait of Raffles. The stamp design was officially launched in the courtyard of Borobudur by Puan Maharani, then Coordinating Minister for Advancements of Human and Culture, accompanied by Rebecca Razavi, the British Consul General to Indonesia and Timor Leste, and Ganjar Pranowo, then the governor of Central Java.

Read any historical book on Borobudur today, and you will most certainly find this narrative of “discovery”. But while adoration for Raffles prevails, it is remarkable that—contrary to what is depicted on those 20,000 stamps—he did not personally go to see the temple in 1814. He was indeed the first European scholar to describe the ancient site in his widely recognised 1817 book, The History of Java, recently translated and re-published in Indonesian language. But this account was based on reports and drawings from the Dutch engineer Hermanus Christiaan Cornelius, whom Raffles had assigned to survey the area following a tip-off from an unnamed local official. Moreover, the description of the Javanese temples in his book fixated on the notion that Hindu and Buddhist monuments had been abandoned and lost their meanings following Javanese conversion to Islam in the early 16th century—a contested colonial narrative that continues to reverberate in Indonesian archaeology and heritage-making today.

But Raffles’s book was thankfully not the only text produced in this period to contain accounts of the ancient Javanese temples and their later significance. The 1815 manuscript Centhini Kadipaten—an exceptional version of a Javanese text broadly known as the Serat Centhini—provides dramatised accounts of visits by Javanese santri (students of Islam) to a handful of Hindu and Buddhist temples across Java during the reign of Sultan Agung of Mataram (1613–1645). Its 12 volumes and 3,500 stanzas compile and retell accounts from older court manuscripts dating back as far as 1616, interlaced with stories borrowed from other Javanese texts and oral traditions beyond the court’s walls. The Centhini Kadipaten manuscript contests the dominant colonial narratives of “abandonment” and “discovery”—and a close reading of its contents tells a different story altogether about the shifting values of ancient Javanese temples.

Authorised heritage-making for ancient sites in Indonesia often gravitates towards memorialisation of colonial narratives. In part, this has been driven by the colonial assumption of rupture in localised attitudes towards ancient monuments in Java following conversion to Islam. This assumption can be traced back to Raffles. In his own words:

The natives are still devotedly attached to their ancient institutions, and though they have long ceased to respect the temples and idols of a former worship, they still retain a high respect for the laws, usages, and national observances before the introduction of Mohametanism. [Emphasis added]

“Idols” here connotes figural representations, or statues, of gods from Hindu and Buddhist traditions, such as the tiered complex of Buddha statues at Borobudur.

Another example can be found in Penataran, a Javanese Hindu temple built in the 12th century, which is also said to have been “discovered” by Raffles in 1815 after a long period of purported neglect. This false yet pervasive impression of “abandonment” was manufactured by colonial scholars such as Raffles by ignoring Islamic (re)production of knowledge and (re)appreciation of Hindu and Buddhist monuments. Until today, accounts from local Muslim communities, particularly those recorded in early modern texts, have never been appropriately acknowledged and considered in the official historiography.

Underpinning this particular heritage construction is the field of archaeology (and, to some extent, art history), in which the primary attitude is to privilege a monument’s original functions and meanings at the time of creation. Hindu-Buddhist sites and materials are then frozen into the period when the local population is thought to have primarily observed them, between the 4th and 15th centuries. Later appropriations in the Islamic context, which may include newly created meanings for these materials, and even those inspired by past values, are mostly deemed ineligible for scientific study within archaeology.

There is a political dimension to why archaeology sustains the colonial framework, seeking to glorify ancient Hindu and Buddhist temples and their original functions. Soekmono, one of the first generation of local archaeologists and known today as the “father” of Indonesian archaeology, was convinced that:

… the period of ancient history also yields a very large number of remains, other than written documents, which are important evidence of the glory of a culture (its architecture), and it is these remains which provide inexhaustible material for archaeology.

This framework helps produce an imagination of past grandeur, especially in the service of history-writing geared towards a particular brand of national identity. Southeast Asian nations tend to engage in archaeology for identity-making by giving prominence to “monumental architecture”. In Indonesia, this architecture includes ancient Hindu and Buddhist temples. Through the process of heritage-isation, these temples are used by the nation-state to celebrate premodern cultural achievements, giving an impression of historical rootedness for the national identity.

Apart from being nurtured along by nationalistic fervour, the framework has also been perpetuated by disciplinary constructions of periodisation and specialisation, with divisions of expertise created along sectarian and chronological lines. This periodisation-cum-specialisation has driven knowledge about broader Javanese cultures to be divided into pre- and post-16th century blocs: Islamic perspectives are exclusively applied in the study of post-16th century materials, while almost never being considered in the study of the pre-16th century Hindu-Buddhist period. Due to this periodisation, rich cultural texts like the Centhini Kadipaten are largely absent from both archaeology and heritage-making for Java’s Hindu-Buddhist monuments.

The dramatised narrative of the Centhini Kadipaten manuscript retells the journeys of three descendants of Sunan Giri, one of the “Nine Saints” (Wali Sanga) believed to have introduced Islam across the island of Java, as well as a fourth figure who married into the family. Siblings Jayengresmi, Jayengsari, and Ni Rancangkapti were forced to disperse across Java after Sultan Agung of Mataram attacked their home, the palace of Giri, a theocratic city-state on the northeast coast. From ransacked Giri, Jayengresmi went on his journey and visited the ruined capital of Majapahit, the temples in Panataran, and the remains of the Padjajaran kingdom along the way. Meanwhile, his brother Jayengsari and sister Ni Rancangkapti were told stories about nearby temples while spending their nights in the Dieng plateau in central Java. The fourth figure in the tale, Mas Cebolang, travelled mainly in the southern region of central Java, where he encountered the temples of Borobudur, Mendut and Prambanan. He would later meet and marry Ni Rancangkapti.

The 1815 manuscript relates to a Javanese genre of literature called santri lelana (wandering Islamic student or scholar). The genre generally concerns a santri scholar exploring life outside the court walls in a vague geographical setting while accumulating new knowledge through encounters and debates with other spiritual figures. In a departure from this style, the Centhini Kadipaten is the first manuscript of its kind to give its stories an existent temporal and spatial setting.

It is also the first to include descriptions of Hindu and Buddhist temples in Java. Many scholars have remarked on these descriptions, yet none have considered them important sources for historical and archaeological studies on Hindu and Buddhist temples. This is partly because the narrative is set during the reign of

The destruction of centuries past should focus the region on preparing for Indonesia’s next mega-eruption.

Fragile paradise: Bali and volcanic threats to our region

Time and place details in the Centhini Kadipaten have compelled comparisons to European travel accounts, and so have attracted some scholarly appreciation. Less appreciated is that the manuscript also has much to teach us about the internalisation of local knowledge, and how it is purportedly written to showcase how the distant past of Java should have been recorded and understood. In many ways, the production of the Centhini Kadipaten became a means to perform Javanese identity against the backdrop of socio-political turmoil in early the 19th century. Its production can be understood as a moral and metaphysical defiance, creating a court-endowed Javanese history in response to then ongoing European-driven knowledge production. It was composed during a time of political disorder in Surakarta, Central Java, prompted by a four-way power contestation between the ruler Pakubuwana IV, the crown prince Mangkunegara III, the British authority in Java (led by Raffles), and the Sepoy troops employed by the British, who planned a failed rebellion in 1815. It should be noted that while Surakarta’s court scribes penned the Centhini Kadipaten, the study of Javanese antiquities by British colonial scholars, including publications such as Raffles’ History of Java, was in full swing.

Considered in this context, the Centhini Kadipaten might have a more tangible link with The History of Java than one would imagine. Foregrounding his discussion on Java’s ancient history, Raffles noted that he was indebted to accounts provided by a few local aristocrats, among them the secretary of Pangeran Adipati of Surakerta (Surakarta). It would be safe to assume that Raffles was referring to Kangjeng Gusti Pangeran Adipati Anom Mangkunagara III, a noble of the Surakarta court, and his “secretary”, or court poet at the time, Yasadipura II. According to tradition, Yasadipura II was one of the principal scribes of Centhini Kadipaten, alongside two other poets, Ranggasutrasna and Sastradipura. If this assumption is correct, then one of Raffles’ important sources for his book was actually involved in producing the Centhini Kadipaten.

Reflecting on questions of remembering and forgetting, one specific episode in the Centhini Kadipaten manuscript can serve as a case study: when Jayengresmi visits the candhi (temple) of Penataran in Blitar, East Java. The visit happens after a sojourn in Trowulan, the capital of Majapahit, where Jayengresmi is accompanied by his two santri-servants, Gathak and Gathuk. In the complex of Penataran, the group observes the relief narrating the Ramayana story at the main temple, and the numeral inscription in one of the smaller temples, recognised today as Candi Angka Tahun (literally the Temple of the Year Numeral). This can be found in lines 29–33 of stanza 20 in Centhini Kadipaten, as below in Modern Javanese transcription and English translation:

Lepas lampahnya dumugi, candhi Panataran Blitar, neng ardi Kelud sukune, sela cemeng kang kinarya, ageng ingkang sajuga, wit ngandhap tumekeng pucuk, ingukir ginambar wayang. |

After walking far, they finally arrived at the candhi of Panataran in Blitar, at the foot of Kelud mountain. The candhi was made of black stones, each stone was big, and, from bottom to top, was carved with images from the wayang (shadow puppet play). |

Radyan gya minggah ing candhi, tundha pitu prapteng pucak, udhunira alon-alon, Gathak Gathuk barangkangan, tyas agung tarataban, tekeng ngandhap Gathuk muwus, Gathak mau gambar apa. |

Raden (Jayangresmi) immediately climbed the candhi, seven levels to reach the top, then went down slowly. Gathak and Gathuk crawled, their hearts trembling, and after they arrived at the bottom Gathuk asked, “Gathak, what were those images from before?” |

Kang ingukir pinggir candhi, lunglungan ceplok kembangan, memper wayang buta kethek, Gathuk ing pangiraningwang, gambare Rama tambak, katara ketheke brengkut, candhi alit tininggalan. |

“Those carved at the edge of the candhi, decorated by flower petals, looked like the wayang monkey giant,” Gathuk guessed, “it was a picture of Rama building a dam, as we could see from his monkey army carrying something.” Then there was a small heirloom temple. |

Lir cungkup wangunaneki, ing sanginggiling wiwara, sinerat sastra Budane, Gathuk matur inggih radian, punika kadiparan, kajenge sastra puniku, pating penthalit tan cetha. |

Resembling a grave’s structure, above its entrance door, the script of Buda was inscribed, and Gathuk said, “Please excuse me Raden (Jayangresmi), what is this, this writing here, jumbled and unclear?” |

Rahadyan ngandika aris, sastra Buda papengetan, sewu rongatus etunge, sangang puluh siji warsa, nalikane akarya, ing sanggar pamujan iku, manthuk-manthuk Gathuk Gathak. |

Raden (Jayangresmi) spoke softly, “this Buda script is to commemorate the temple, it is read as one thousand two hundred and ninety one, which is the year when the candhi was made.” In that place of worship, Gathuk and Gathak were nodding. |

The word candhi has been adopted by the Indonesian language (candi) to refer to ancient Hindu and Buddhist temples. It comes from the Old Javanese lexicon, primarily denoting a holy sanctuary where gods descend upon worship. Yet in Modern Javanese, the word can gloss over multiple meanings, including a cemetery, tomb, and mausoleum. In a Javanese–Dutch dictionary published in 1901, candhi is described as “the stones, between and under which the ashes of the burnt corpse of a deceased person were ordered in olden times; a cemetery or mausoleum built over the ashes of a deceased person; a stone temple of ancient times.’’ These meanings may reflect 19th-century Javanese perspectives on the remains of Hindu and Buddhist temples. A closer reading of the word candhi could then reveal how meanings were accumulated over time, with original understandings perhaps at times manifestly forgotten, even while lingering obscurely in the collective memory, which could be recollected and reinterpreted through various forms of knowledge.

Numeral inscription of 1291 of Javanese Era (1369 CE) at Candi Angka Tahun, Penataran. (Photo: author)

Another notable term from the passage above is buda, which generally signifies the distant pre-Islamic past in Java. While derived from the word Buddha, buda typically stood for the hybrid Hindu-Buddhist religion, but also at times included animism in Java. The use of this term in the early 19th century appears to signal the beginning of Javanese fascination with the pre-Islamic past. The term buda then seems to encompass all things that happened before Islam took hold of the Javanese spiritual imagination, starting from the 16th century. The term is notably used in the passage above to refer to the type of script used in the numeral inscription on the temple. We know that the script here is Old Javanese, known as kawi by later Javanese literati. Older texts like Ramayana and Bharatayuddha are written in kawi. Mastery of such texts was considered paramount for court elites to understand Islam in Java, giving one an authoritative voice within the court. This is implied in the passage above when the one who reads aloud the numeral is Jayengresmi, a prince from the theocratic city-state of Giri. We should also note that the numeral “1291” is read correctly, thus debunking the colonial presumption that 19th-century Javanese people could not read Old Javanese inscriptions.

Two panels portraying Rama’s monkey army building a dam, Penataran. Photo by Anandajoti Bhikku (CC BY 2.0)

The passage further reveals that early modern (Islamic) Javanese could understand the stories represented on reliefs in ancient temples. This may be helped by the fact that the Old Javanese Ramayana is one of the pre-16th-century texts to have been copied by the court of Mataram in the second half of the 18th century. At Penataran, it was Gathuk, one of the servants accompanying Jayengresmi, who recognised the panel describing the monkey army’s construction of a water bridge. Considering Gathuk’s lower social status, this episode may reflect the popularity of Rama’s story, frequently retold in public recitals and wayang performance. The connection between the relief and its wayang portrayals is evident in that the figures are portrayed in the carving in the style of shadow puppet figures. While other older tales might have been left forgotten, this continued remembering of Ramayana speaks to early modern Javanese and Islamic curation, in terms of what knowledge from the past is still considered necessary, despite originating from distinct sectarian practices.

Keeping this reading of Centhini Kadipaten in mind, the “abandonment” narrative that has been embedded into heritage-making around Java’s Hindu and Buddhist temples becomes a more ambiguous colonial and postcolonial framework. From the early 19th century onwards, colonial administrators-cum-scholars co-opted

The destruction of centuries past should focus the region on preparing for Indonesia’s next mega-eruption.

Fragile paradise: Bali and volcanic threats to our region

Re-introducing local texts is one strand in the decolonisation of thinking about the narratives of ancient temples in Indonesia. This strand does not intend to excavate something pre-colonial, but instead aims to retrieve localised knowledge from the cracks and fissures born out of local-colonial tensions. In order to better grasp nuanced historical contexts, local texts and artistic manifestations must be read closely. By studying history in this way, with sensitivity to political, social, and cultural contexts at the time of production, we relocate and observe what is in those cracks and fissures. It is through localised knowledge, such as the stories attested in the Centhini Kadipaten, that we can see how Hindu and Buddhist temples in Java were never truly “dead”, and that local people continued, and still continue, to re-create meanings and values around them. This new understanding should engender a more inclusive heritage practice, by acknowledging the diverse ways of interpreting ancient sites.

• • • • • • • • • •

This post is part of a series of essays highlighting the work of emerging scholars of Southeast Asia published with the support of the Australian National University College of Asia and the Pacific.

The post Javanese candhi beyond abandonment and discovery appeared first on New Mandala.

This post was originally published on New Mandala.

As activist groups around the world observe December 1 — flag-raising “independence” day for West Papua today marking when the Morning Star flag was flown in 1961 for the first time — Kristo Langker reports from the Highlands about how the Indonesian military is raising the stakes.

SPECIAL REPORT: By Kristo Langker in Kiwirok, West Papua

While DropSite News usually reports on, and from, parts of the world where the US war machine operates, in this story, the weaponry in question is made by a multinational French weapons manufacturer and Chinese manufacturer.

However, you will see the structure is the same — the Indonesian government using drones and helicopters to terrorise and displace the people of West Papua, while the historical reason imperial interests loom over the region stems from a US mining project in the 1960s.

The videos in this story are well worth watching — exclusive interviews with the guerilla group fighting off the drones and airplanes with bows and arrows.

On 25 September 2025, Lamek Taplo, the guerilla leader of a wing of the West Papua National Liberation Army (Tentara Pembebasan Nasional Papua Barat, or TPNPB), left the jungle with his command to launch a series of raids on Indonesian military posts.

Indonesia had established three new military posts in the Star Mountains region in the past year, according to NGO Human Rights Monitor, with sources on the ground telling Drop Site News that nearby civilian houses and facilities — including a church, schools, and a health clinic — had been forcibly occupied in support of the military build-up.

5 Indonesian soldiers shot

Despite being severely outgunned, the command shot five Indonesian soldiers, killing one, while suffering no casualties themselves, according to Taplo and other members of his group.

The raids continued for three more days. The command shot the fuselage of a helicopter and burned five buildings that Taplo’s group claimed were occupied by Indonesian security forces.

Taplo was killed less than three weeks later by an apparent drone strike. During an October 13 interview a week before his death, Taplo, a former teacher himself, told Drop Site why TPNPB targeted a school:

“It’s because they (Indonesian military) used it as their base. There’s no teacher — only Indonesians. I know, because I was the teacher there, too . . . Indonesia sent ‘teachers’. However, they’re actually military intelligence.”

Indonesia has laid claim to the western half of New Guinea island since the 1960s with the backing of the US. For the past year, the Indonesian military has ramped up its indiscriminate attacks on subsistence farming villages, especially those that deny Indonesian rule.

The military presence has been growing exponentially after the October 2024 inauguration of President Prabowo Subianto, who is implicated in historic massacres in Papua from his time as commander of Indonesia’s special forces — called Komando Pasukan Khusus or “Kopassus”.

According to witnesses interviewed in Kiwirok and its surrounding hamlets, and documented in videos, there are now snipers stationed along walking tracks, and civilians have been shot and killed attempting to retrieve their pigs.

Indonesian retaliated

Indonesia immediately retaliated against TPNPB’s September attacks by sending two consumer-grade DJI Mavic drones, rigged with servo motors, to drop Pindad-manufactured hand grenades.

One drone targeted a hut that Taplo claimed did not house TPNPB but belonged to civilians.

No one was killed as the grenade bounced off the sheet metal roof and exploded a few meters away. The other drone flew over a group of TPNPB raising the Morning Star flag of West Papua but was taken down by the guerrillas before a grenade could be dropped.

Ngalum Kupel TPNPB celebrating the capture of a drone. September 28, 2025.

Holding the downed drone and grenade, Taplo likened the ordeal to Moses parting the Red Sea for the escaping Israelites: “It’s like Firaun and Moses . . . It was a miracle.”

Then joking: “The bomb (grenade) was caught since it’s like the cucumber we eat.”

Over the next few weeks, a series of heavier aerial bombardments followed.

Video evidence

Videos taken by Taplo show two Embraer EMB 314 Super Tucano turboprop aircraft darting through the air, followed by the thunderous sound of ordnance hitting the mountains.

Despite the fact that thousands of West Papuans have been killed in bombings like these since the 1970s, Taplo’s videos are the first to ever capture an aerial bombardment from the ground in West Papua, owing to the extreme isolation of the interior.

In fact, many highland West Papuans’ first contact with the outside world was with Indonesian military campaigns.

Ostensibly a counter-insurgency operation against a guerrilla independence movement, these bombings are primarily hitting civilians — tribal communities of subsistence farmers.

The few fighters Indonesia is targeting are poorly armed lacking bullets, let alone bombs — and live on ancestral land with their families. The most ubiquitous weapon among these groups remains the bow and arrow.

Taplo told Drop Site the bombings began on Monday, October 6.

“Firstly they (Indonesia) did an unorganised attack: they dropped the bomb randomly . . . they just dropped it everywhere. You can see where the smoke was coming from.

“Even though it was an Indonesian military house, they just dropped it on there anyway. That was the first one; then they came back. The first place bombed after was a civilian house; the second was our base.”

Embraer EMB 314 Super Tucano bombing and strafing the mountains. October 6, 2025

Former Dutch colony

West Papua was a Dutch colony until 1962, when Indonesia, after a bitter dispute with the Netherlands, secured Washington’s backing to take over the territory.

Just three years after Washington tipped the scales in favour of Indonesia in their dispute with the Netherlands, the nationalist Indonesian President Sukarno was ousted in a US-backed military coup in 1965.

Hundreds of thousands of Indonesian leftists (or suspected leftists) were killed in just a few months by the new regime led by General Suharto.

Indonesia’s acquisition of West Papua is often treated as an event peripheral to this coup, yet both events held a symbiotic relationship that would become the impetus for many of the mass killings perpetrated by Indonesia in West Papua.

Forbes Wilson, the former vice-president of US mining giant Freeport, visited Indonesia in June 1966, and in his book, The Conquest of Copper Mountain, he boasts that he and several other Freeport executives were among the first foreigners to visit Indonesia after the events of 1965.

Wilson was there to negotiate with the new business friendly Suharto regime, particularly regarding the terms of Freeport’s Ertsberg mine, which was set to be located under Puncak Jaya — the tallest mountain in Oceania.

This mine eventually became the world’s largest gold and copper mine and Indonesia’s largest single taxpayer. The mine’s existence was one of the primary reasons Indonesia gained international backing to launch a vicious Malanesian frontier war against the native and then-largely uncontacted Papuan highlanders.

The “war” continues to this day, though it is largely unlike other modern conflicts.

Like frontier ‘wars’

Instead, the concerted Indonesian attacks are most comparable to the US and Australian frontier wars. Indonesia, one of the world’s largest and most well-armed militaries, is steadily wiping out some of the world’s last pre-industrial indigenous cultures and people.

West Papuans have fought back, forming the Free Papua Movement (Organisasi Papua Merdeka, or OPM) and its various splinter armed wings, whose most prominent one is the TPNPB.

Due to the impenetrable terrain of the mountain highlands, the Indonesian military has difficulty fighting the TPNPB on the ground, often instead resorting to indiscriminate aerial bombardments.

The TPNPB’s fight is as much about West Papuan independence as it is an effort by localised tribal communities and landowners using whatever means to prevent Indonesian massacres and land theft.

“No army has ever come to protect the people. I live with the people, because there’s no military to protect my people,” Taplo said in a video sent just before his death.

“From 2021 until this year 2025, I have not left my land; I have not left the land of my birth.”

In October 2021, the Indonesian military launched one of these bombing campaigns in the remote Kiwirok district and its surrounding hamlets in the Star Mountains — deep in the heart of the island of New Guinea.

Little information

Because of this isolation, very little information about these bombings trickled out of the mountains — save for a few images of unexploded mortars and burning huts.

Only a handful journalists, including the author of this article, have been able to visit the area, and it took years and multiple visits to the Star Mountains for the full scale of the 2021 attacks to be reported.

It was eventually revealed that the Indonesian assaults included the use of most likely Airbus helicopters that shoot FZ-68 2.75-inch rockets, designed by French multinational defence contractor Thales, and reinforced by Blowfish A3 drones manufactured by the Chinese company Ziyan.

These drones boast an artificial intelligence driven swarm function by which they litter villagers’ subsistence farms and huts with mortars improvised with proximity fuzes manufactured by the Serbian company Krušik.

A largely remote, open-source investigation by German NGO Human Rights Monitor revealed that hundreds of huts and buildings were destroyed in this attack. More than 2000 villagers were displaced, and they still hide in makeshift jungle camps.

“The systematic nature of these attacks prompts questions of crimes against humanity under the Rome Statute,” the report noted. Additionally, witnesses interviewed by this author gave the names of hundreds who died of starvation and illness after the bombings.

With little food, shelter, weapons, or even internet to connect them to the outside world, many of the thousands of Ngalum-Kupel people displaced since 2021 are displaced again — likely to die without anyone knowing — mirroring countless Indonesian campaigns to depopulate the mountains to make way for resource projects.

Long-term effects

The impact of the latest wave of attacks in October 2025 is likely to be felt for years, as the bombs destroyed food gardens and shelters and displaced people who were already living in nothing more than crowded tarpaulins held up by branches, while having already been forced to hide in the jungle after the 2021 bombings.

“It is the same situation with Palestine and Israel — people are now living without their home,” said Taplo.

On 6 October 2025, Indonesia retaliated further, deploying two aircraft that aviation sources confirmed to be Brazilian-made Embraer EMB 314 Super Tucano turboprops. These planes were filmed bombing and strafing the mountains.

Drop Site confirmed that some of the shrapnel collected after these attacks is from Thales’s FZ 2.75-inch rockets — the same rockets used in the 2021 attacks.

In January this year, Thales’s Belgium and state-owned defence company, Indonesian Aerospace, put out a press release titled: “Indonesian Aerospace and Thales Belgium Reactivate Rocket Production Partnership,” which boasted the integration of Thales designed FZ 2.75-inch rockets with the Embraer Supertucano aircraft.

Though these were not the only ordnance deployed, some of the impact zones measured over 20m, and the shrapnel found in these craters was far heavier and larger than that from the Thales rockets.

Shrapnel ‘no joke’

“It’s no joke. It was long and big. It could destroy a village . . . ” said Taplo before picking up a piece of shrapnel around 20cm long.

“This is five kilograms,” he said, weighing the remnants.

Inspecting Impact zone from bombings on 6 October 2025.

A former Australian Defence Force air-to-ground specialist told Drop Site that the large size of the shrapnel and nature of the scarring and cratering indicate that the bomb was not a modern style munition. It was most likely an MK-81 RI Live, a variant of the 110kg MK-81 developed and manufactured by Indonesian state-owned defence contractor Pindad.

“This weapon system is unguided, and given the steep terrain, it is unlikely that a dive attack could easily be used, providing the enhanced risk of collateral damage or indiscriminate targeting given the weapons envelope,” the specialist said. Pindad did not respond to Drop Site’s request for comment.

Photos from a February Pindad press release about the development of the MK-81 RI Live show these bombs loaded on an Indonesian Embraer Supertucano.

A week later, Indonesia hit again. At around 3am, on October 12, a reconnaissance aircraft flew over the camp where Taplo’s command and their families were sleeping, waking them just in time to evacuate before another round of bombs were dropped == again, most likely the MK-81 RI Live.

Bomb strike on video

Taplo captured the bomb’s strike and aftermath on video. Clearly shaken, he makes an appeal for help, saying “UN peacekeeping forces quickly come to Kiwirok to give us freedom, because our life is traumatic . . .

“Even the kids are traumatised; they live in the forest, and seek help from their parents, ‘Dad help me. Indonesia dropped the bomb on the place I lived in.’”

On the morning of October 19, a drone dropped a bomb on a hut near where Taplo was staying. Initially, the bomb didn’t detonate, leaving enough time for civilians to evacuate the area.

After the evacuation, Taplo and three men returned to remove the ordnance, which then detonated and instantly killed Lamek Taplo and three others — Nalson Uopmabin, 17; Benim Kalakmabin, 20; and Ike Taplo, 22.

Speaking to Drop Site just hours after Taplo was killed, eyewitnesses say the drone was larger than the DJI Mavics deployed earlier and were similar in size to the Ziyan drones from 2021.

Photos taken of the remnants of the bomb show the tail of what was most likely an 81mm mortar.

“The presence of drones — similar to that of DJI quadcopters and [with] improvised fins for aerial guidance — have been employed [just as] ISIS used those weapons systems in Syria,” the former Australian Defence Force air-to-ground specialist told Drop Site.

Plea to Pacific nations

On October 26, civilians in Kiwirok sent an appeal to the government of Papua New Guinea and other Pacific Island nations. So far, there has been no response, despite these bombings occurring on Papua New Guinea’s border.

The last communication Drop Site received from Kiwirok indicated that the bombings were continuing and the mountains still swarmed with drones — limiting any chance of escape.

Pictures posted on social media in November by members of Indonesian security forces, those stationed in Kiwirok, give some insight into the level of zeal with which Indonesia is fighting this campaign.

An Indonesian soldier can be seen wearing a T-shirt emblazoned with a skull wearing night vision goggles, a gun, and a lightning bolt forming a cross behind it. The caption reads “Black Zone Kiwirok.”

Another photo shows soldiers sitting in front of a banner which reads “Kompi Tempur Rajawali 431 Pemburu” — a reference to the elite “Eagle Hunter” units set up in the mid 1990s by then-General Prabowo Subianto to hunt down Falantil guerillas in Timor Leste.

As there has been no record of these units being deployed in Papua — nor of an “Eagle Hunter” unit made up of soldiers from the 431st Infantry Battalion — it is unclear whether these banners are just Suharto-era nationalism on display, or if they signify that these units have been revived.

On his final phone call with the outside world, just before the signal cut out, Taplo vowed to continue the TPNPB’s fight: “We will fight for hundreds of days . . .

“We will fight . . . This war is by God. We have asked for power; we have prayed for nature’s power. This is our culture.”

Republished from DropSite News.

This post was originally published on Asia Pacific Report.

Indonesian President Prabowo Subianto surprised many on 11 June 2025 when he mentioned in a speech at the Indo Defence Expo & Forum that according to a study purportedly published a few weeks earlier, “the Netherlands took resources from Indonesia valued at US$31 trillion in today’s terms during their colonisation of our country”. He explained that this was equivalent to almost 18 times Indonesia’s current GDP of around US$1.5 trillion.

The number of US$31 trillion reverberated in Indonesian social media. By contrast, in The Netherlands only the Jakarta correspondent of De Volkskrant reported it, adding that the origin of the number puzzled historians of Indonesia.

It is unclear why Prabowo mentioned this number. It appears he intended to justify Indonesia’s additional military expenditure to safeguard Indonesian sovereignty and prevent his country from ever being colonised again. It is also unclear what study the president referred to. An extensive online search yielded no trace of a publication that accounted for the extraordinary amount of US$ 31 trillion The Netherlands may have taken from Indonesia.

If there is such a study, it would be a significant intervention in an ongoing international discussion among scholars of international law, history, and international relations about the need for former colonising countries to pay retribution for the colonial past. This discussion was partly informed by the 2012 book Why Nations Fail, by the winners of the 2024 Nobel Prize in economics, Daren Acemoglu and James Robinson. They argued that “extractive institutions” related to slavery and colonialism had lasting and debilitating consequences for many countries’ later economic development.

In 2017 an article in Third World Quarterly by the political economist Bruce Gilley, “The Case for Colonialism”, also prompted considerable discussion about the demerits of colonial rule. Contributing to the discussion too was a 2017 study by Indian historian Utsa Patnaik concluding that British colonisation of India between 1765 and 1938 had benefited the United Kingdom by US$45 trillion. All this energised opinion that European states should pay reparations to the countries they had colonised in the past—though this debate was largely grounded in ethical objections to past practices of slavery and colonialism, rather than about how to quantify the damage caused by such institutions in order to establish the size of retribution to be paid.

During 2025 this debate was stepped up several notches. In February, the African Union Heads of State meeting set “Justice for Africa and People of African Descent through Reparations’ as its annual theme. This echoed earlier calls for reparations articulated by Caribbean members of the Caricom Reparations Commission. A submission to the UN General Assembly in September from the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights reiterated the call for “reparatory justice for legacies of enslavement … colonialism and successive racially discriminatory policies and systems”, calling for “adequate, effective and prompt reparation”.

Recent statements from international organisations such as Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International support the call for reparations for colonialism and slavery. The UN Special Advisor on Africa is organising an “Africa 2025” conference in December with a key session “on reparations, broadening the lens beyond compensation to embrace a vision of structural justice”.

Although this flurry of debate in 2025 is focused on Africa, earlier publications on India indicate that it may just as well apply to parts of Asia subjected to slavery and colonialism in the past. But unlike India, Indonesia hardly featured in this debate. As far as there was public discussion about Indonesia’s colonial past during those years in Indonesia and/or The Netherlands it related to Indonesia’s independence war (1945–1949), especially regarding what was considered to have been “extreme violence” (extreem geweld) on the part of Dutch armed forces during this conflict. It informed the Dutch King’s apologies delivered during a visit to Indonesia in March 2020—not for the entire colonial past, but for the “extreme violence”.

The Netherlands offered apologies and paid compensation to family members of victims of extreme violence in West Java and South Sulawesi. It also financed an extensive study project that in 2022 published multiple volumes on the Dutch involvement in Indonesia’s war of independence 1945–1949 and the use of extreme violence.

Even in that context, there were no attempts to link the Dutch apologies to the broader issue of the effects of Indonesia’s colonial past on Indonesia’s development prospects. That was possibly because the evidence for the broader negative effects of colonial rule on Indonesia’s economy may be difficult to muster.

For example, a study by economists Melissa Dell and Benjamin Olken in 2020 used the methodology developed by Acemoglu and Robinson to examine the lasting consequences of the “extractive institution” of the Cultivation System in Java. From 1820 to 1870, the colonial government required the farming population of Java to contribute labour and land for the cultivation of export crops, particularly sugar, as a tax in kind. Dell and Olken found that villages that were in the 1850s were involved in sugar cane production are in the 2010s “more industrialized, have better infrastructure, are more educated, and are richer than nearby counterfactual locations”—in other words, the Cultivation System did not have lasting detrimental consequences for Java.

Nevertheless, President Prabowo mentioned that The Netherlands extracted US$31 trillion from Indonesia during the colonial years. Where did this number come from? How was it approximated? And will it be the basis for an Indonesian claim for reparations payments from The Netherlands?

Identifying the cumulative effects or costs of colonisation on colonised countries is a long-discussed issue. It is captured by the term “colonial drain”, first articulated by Indian scholar and Member of the British parliament Dadabhai Naoroji in 1901. He argued that British rule in India had led to a transfer of wealth to Great Britain to the detriment of economic development in British India.

Studies sought to quantify this “colonial drain” from India, although an unambiguous definition of the term remained elusive. Analysing the evidence, prominent Indian economic historian Kirti Chaudhuri in 1968 found the “drain” argument “by no means true”. His colleague Tirthankar Roy in 2022 concluded that Patnaik’s 2017 estimate of “colonial drain” of US$45 trillion was based on “dreadfully bad economics”. Despite the lack of conclusive evidence, the term is still widely used in explanations of India’s economic underdevelopment.

By contrast, the “colonial drain” phrase was hardly used in past studies of the relations between The Netherlands and colonial Indonesia. Indonesia-born economist Arnold Berkhuysen first explored its relevance in his 1948 PhD thesis at the University of Leiden. Using a balance of payments perspective, he established that funds flowing from colonial Indonesia were mostly payments related to Dutch investments in Indonesia. He argued that those investments would not have taken place without the overseas payments of interest and dividends.

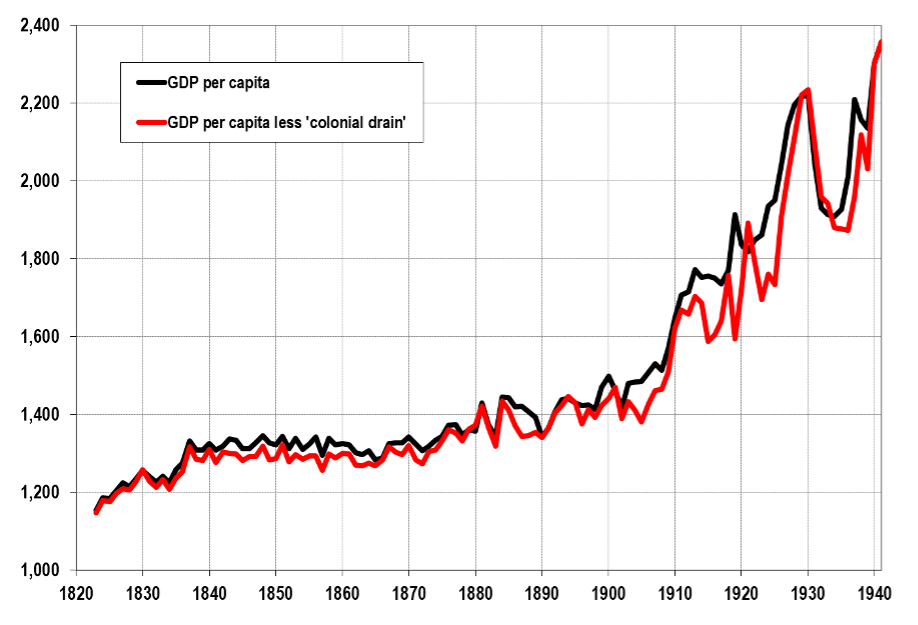

The University of Groningen Professor of Development Economics Angus Maddison in 1989 used the commodity trade surplus of India and of Indonesia as a proxy for the “colonial drain”. He identified an annual average “drain” of 0.7% of Indonesia Net Domestic Product (NDP) during 1698–1700, rising to 10.6% during 1921–1938, compared to an annual average of 1.5% of India’s NDP during 1868–1938.

In 1993, while I was a PhD student of Maddison’s, I used more detailed balance of payments data to argue that Indonesia since independence in the 1940s also had a commodity trade surplus, because it continued to be a net importer of services. Particularly, the services of foreign loans and foreign investments required overseas remittances of interest and dividends, while Asian and European expatriate employees working in Indonesia remitted their savings. After reducing the commodity trade surplus with these factor payments, he estimated an annual average “drain” of 2.5% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) during 1823–1938 and 2.4% during 1949–1990.

FIGURE 1: GDP per capita in colonial Indonesia with and without “colonial drain”, 1823–1941 (Source, Pierre van der Eng, 1993. “The Colonial Drain from Indonesia, 1823-1990”, Working Paper, Australian National University)

In 2010, University of Utrecht Professor of Economic History, Jan Luiten van Zanden analysed the impact of “colonial drain” on the economy of Indonesia’s main island of Java during the 19th century. The Cultivation System led to significant annual net transfers of funds from Java to The Netherlands. Van Zanden assumed that Java’s net transfers to the Netherlands during 1820–1879 were a minimum estimate of “drain”, while the commodity trade surplus during 1822–1880 was a maximum estimate. He found that on average during 1820–1880 Java’s GDP was “drained” by a minimum of 4 and a maximum of 7% per year, on average 5.5%.

Van Zanden’s 2010 article is readily available online and may have been used in the publication to which President Prabowo referred on 11 June 2025. Maybe this publication applied the annual average of 5.5% of GDP during 1820–1880 to all years of Dutch colonial rule. Many in Indonesia believe that to have been 350 years, but maybe it only started in 1619 when the Dutch East India Company established itself in Jakarta. And maybe it ended in 1942 when Japan occupied Indonesia. These 322 years multiplied by an annual 5.5% results in an estimated accumulation of “colonial drain” equivalent to 1,771% of Indonesia’s GDP.

Rounded up, this is the same as the 18 times of Indonesia’s GDP that Prabowo’s figure implies. Except that Indonesia’s GDP in 2024 was US$1.36 trillion, not the US$1.5 trillion the president mentioned. Maybe Prabowo expects higher economic growth during 2025. However, even with an implausible 10% growth during 2025 to reach a GDP of US$1,500 billion, 18 times that amount adds up to US$27 trillion, not to US$31 trillion—maybe a miscalculation in the publication to which the President referred.

Either way, it seems very likely that the estimate of US$ 31 trillion of resources taken by The Netherlands from Indonesia in the past had to have been based on a back-of-the-envelope speculative calculation. If it was like the crude calculation above, there are some obvious shortcomings.

Firstly, there is no evidence that either net transfers or the trade surplus from Java during 1820–1870 are a suitable proxy for the “colonial drain” over all of the 322 (or 350) years of Dutch presence in Indonesia.

Secondly, the current value of the accumulated amount of “colonial drain” has to be estimated with Indonesia’s past GDP, not its GDP in 2024 or 2025. Indonesia’s GDP during the colonial years was a lot smaller. For example, corrected for price changes, Indonesia’s GDP in 1880 was just 1% of GDP in 2024 and in 1941 just 4%. Therefore, the value of the estimated “drain” must be between 1% and 4% of US$31 trillion as well. That would make it between US$310 and US$1.24 trillion—still a significant sum.

Thirdly, the assets of the colonial government and of foreign companies (Dutch, British, American, etc.) accumulated particularly in colonial Indonesia during the period between 1890 and 1940, financed with investments in the shares of these companies, reinvested excess earnings of companies and acquisitions of company and government bonds. Such investments gave rise to increasing remittances of dividends and interest on foreign investment—which explain Indonesia’s trade deficits that were part of the ways in which Maddison and Van Zanden’s estimated the “colonial drain” from Indonesia.

But the investments in the tangible assets of the colonial government and of foreign companies—agricultural estates, factories, railways, port facilities etc.—never left Indonesia. Ownership of public assets were transferred from the colonial government to the government of Indonesia in December 1949. And President Sukarno nationalised the assets of most foreign companies between 1958 and 1965.

It seems unlikely that the number mentioned by President Prabowo will lead to an Indonesian claim for payments from The Netherlands. In part because a claim of US$ 31 trillion is impossible to substantiate. But mainly because any claims of Indonesia on The Netherlands have already been formally settled. First when both countries agreed on the transfer of public assets when they signed the bilateral agreement in December 1949 that formalised Indonesia’s independence. Secondly, in September 1966, when both countries signed a bilateral agreement arranging compensation for Indonesia’s nationalisation of Dutch-owned assets in 1958.

In addition, a claim could sour bilateral relations and have consequences for the constructive elements of those relations. Including, Dutch companies again holding sizeable investments in Indonesia worth US$ 21 billion at the start of 2024, according to the International Monetary Fund. And perhaps more importantly, including that the recruitment of players with Indonesian heritage and coaches in The Netherlands contributed to the success of Indonesia’s national team in international football, which only just missed out on qualifying for the 2026 World Cup. After all, President Prabowo is a proud supporter of Indonesia’s national football team.

The post Colonial rekening: what does the Netherlands owe Indonesia? appeared first on New Mandala.

This post was originally published on New Mandala.

On 29 September 2025 a multi-story musala (prayer space) collapsed at Pesantren Al-Khoziny in Sidoarjo, East Java, killing at least 61 people. A similar tragedy occurred again about a month later on 29 October, when the roof of a female student dormitory collapsed at Pesantren Syekh Abdul Qodir Jaelani in Situbondo, East Java, claiming the life of one student.

The level of anger and breadth of debate that followed—from demands for criminal investigations and critiques of pesantren governance structures to reflections on how pesantren constitute a distinct subculture within Indonesia’s educational and social systems—illustrate common perceptions about the importance of pesantren in Indonesian society. Observers have argued that pesantren occupy a key role in shaping grassroots political outcomes, whether through the political socialisation of santri (students), the broader authority of pesantren networks in local governance and policy debates, or the general political influence of kyai (religious leaders).

Without denying the significance of these findings, we nonetheless lack some basic empirical foundations for systematically measuring the social and political effects of pesantren. Claims about the importance or uniqueness of pesantren often rest on a handful of notable—and likely atypical—cases, such as Pesantren Tebuireng, which produced national leaders like Gus Dur and Ma’ruf Amin, or Pesantren Al-Mukmin in Ngruki, associated with allegations of terrorism. To more systematically understand the place, role, and effects of pesantren in Indonesian society as a whole, we first need answers to fundamental questions: how many pesantren are there? Where are they located? What are their organisational affiliations? Without such baseline information, it remains difficult to ascertain how prevalent pesantren truly are and how far-reaching their influence extends.

This piece takes a step forward by providing systematic, nationally representative background information on Indonesia’s pesantren landscape. Rather than engaging in an in-depth look at few pesantren, it embraces a bird’s-eye view of pesantren across the archipelago. The analysis addresses key descriptive questions about the number, location, organisational affiliation, and growth of pesantren over time, and offers preliminary evidence on how pesantren presence correlates with political outcomes.

Data for this exercise was scraped from the Ministry of Religious Affairs’ (MORA) Education Management Information System (EMIS). First introduced in the early 2000s, EMIS is a MORA’s effort to monitor and supervise religious educational institutions, which include pesantren and madrasah. School administrators enter data into the system following specific forms tapping into different information. Information recorded from each institution includes the number of educators, the number of students, available classrooms and other facilities, founding year, and affiliation, among others.

Interested users may access a subset of this dataset on my website. This dataset includes records on all pesantren, but omits several columns such as bank account information and staff contact details.

The simplest analysis to do with the dataset would be to understand how many pesantren are there and where they are located. This question turns out to be more complicated than it looks.

The EMIS website indicates that there are 42,391 pesantren. However, 20 of these records are duplicates and, out of the non-duplicates, 23 have broken links, which means their data could not be retrieved. We can thus reasonably assert that there are at least 42,348 pesantren in Indonesia. Figure 1 visualises the distribution of these pesantren at the district (kabupaten/kota) level. Some districts are shaded grey, which means that I was unable to link location information of the pesantren data with the GADM (Global Administrative Areas) map I used to create the choropleth.

One notable pattern in the figure concerns how districts in West Java and Banten tend to have the most pesantren. Is it simply because districts there are more populated than other districts in the country?

Figure 2 offers a more nuanced picture by showing the density of pesantren—that is, how many pesantren there are for every 10,000 Muslim residents in the district. The latter information was based on the 2010 census. The general pattern remains the same. Banten and West Java districts have the highest pesantren densities. However, districts in Aceh have darker shades than they are in Figure 1. In other words, even though there are fewer pesantren in Aceh than in Banten or West Java, once we account for population size, Aceh districts are generally comparable to West Java ones (though perhaps not Banten ones) in how prevalent pesantren are.

The next interesting exercise would be to unpick the affiliations of these pesantren. One notable feature of EMIS is that it asks pesantren to indicate their organisational affiliation. Overall, about 77.5% of pesantren indicate affiliation with Nahdlatul Ulama (NU) and about 15.6% indicate that they are independent or unaffiliated. The remaining 7% indicate various affiliations, such as with Muhammadiyah (1.54%), Nahdlatul Wathan (0.84%), and the Persatuan Tarbiyah Islamiyah (PERTI, 0.42%).

Figure 3 presents the proportion of NU pesantren in each district. In the vast majority of districts, the pesantren landscape is dominated by NU. However, some interesting exceptions are evident. In Aceh, NU pesantren tend to be less dominant. Of all pesantren in Aceh, only 23.3% indicate an affiliation with NU. The vast majority (64.9%) indicate being unaffiliated. PERTI also has a quite significance presence in the province, accounting for about 4.4% of the pesantren there.

Independent pesantren are also dominant in East Nusa Tenggara (NTT) and Central Sulawesi, where they account for 46.3% and 34.6% of the pesantren, respectively. The most popular affiliations differ in NTT and Central Sulawesi, however. In NTT, after NU at 29.3%, Muhammadiyah (12.20%) and Hidayatullah (4.9%) are the most popular affiliations. In Central Sulawesi, after NU at 27%, the most popular affiliations are Al Khairaat (18.05%) and DDI or Darud Dawah wal Irsyad (6%).

Having examined spatial variation, we can also look at temporal variation or how the number of pesantren grew over time. EMIS asked pesantren to indicate their founding year in both international and Islamic calendars. Unfortunately, many of the entries look implausible, and judgment calls have to be made to keep only pesantren with plausibly valid information about their founding year in the dataset.

First, I removed 3,010 pesantren that indicated founding years earlier than 1475 AD. This is the founding year of Pesantren Alkahfi Somalanguk, which some regard as the oldest pesantren in Indonesia. Second, I removed 33 pesantren that indicate founding years after 2025—the current year. Lastly, I removed 7,628 pesantren whose founding year in the international calendar does not match its founding year in the Islamic calendar. Such a mismatch makes it impossible for an analyst to decide whether to use information from the international calendar or the Islamic calendar. It might also indicate sloppy data entry. Overall, 29,305 pesantren have information about founding year that I consider valid.

Figure 4 draws from this information and presents the cumulative number of pesantren between 1966 and 2024. I treat this growth chart as a disrupted time series and draw two regression lines, one for the New Order era and the other for the post-Suharto era. This allows us to compare the pattern of pesantren-building during the two eras.

Two patterns are evident from this figure. First, it is obvious that the growth rate of pesantren in the post-Suharto era is higher than the rate during the New Order, as evidenced by the steeper slope of the post-Suharto regression line. This conforms to what we know about how Indonesia’s democratisation was accompanied by a religious resurgence.

Second, we can actually observe a minor spike in the number of pesantren starting in early 1990s. There, the number of pesantren is higher than what the New Order regression line predicts. This nicely reflects Suharto’s growing affinity with Islam at the time, evidenced among others by the founding of the Indonesian Association of Muslim Intellectuals (ICMI) in 1990 and Suharto’s hajj pilgrimage in 1991.

Figure 5 breaks down this growth by organisational affiliation. It is evident that much of the growth was driven by the proliferation of NU pesantren. At the start of the New Order, NU pesantren numbered 1,428 and non-NU pesantren 258. By the time Suharto was removed from power in 1998, there were 7,764 NU and 1,833 non-NU pesantren. By 2024, these numbers grew to 20,620 NU and 6,134 non-NU pesantren. It seems that, at least when it comes to pesantren building, the religious resurgence that followed Indonesia’s democratisation has not affected all Muslim organisations equally.

Lastly, it is interesting to measure whether the presence of pesantren may correlate with electoral outcomes. It goes without saying that correlation does not necessarily mean causation. But ascertaining how pesantren density may be associated with electoral outcomes is a foundational step in understanding how pesantren are significant not only socially but also politically.

I start by examining how the number of pesantren in a district correlates with the vote share of Joko Widodo (Jokowi) in the 2014 and 2019 presidential elections. The presidential elections were often portrayed as a competition between Jokowi’s nationalist camp and Prabowo’s Islamist supporters. To the extent that pesantren correlates with religious sentiment and identity, we should observe a negative correlation between the number of pesantren and Jokowi’s vote share.

Figure 6 shows exactly this pattern. Each dot reflects a district. The X axis represents the logged number of pesantren in the election year and the Y axis represents Jokowi’s vote share. The negative correlations indicate that the more pesantren a district had, the lower the vote share of Jokowi in that district.

Interestingly, the correlation was weaker in 2019 than 2014. This might be a result of the Ma’ruf Amin effect. By having Ma’ruf, a popular NU cleric and former chairman of the Indonesian Council of Ulama (MUI) as running mate, Jokowi was able to weaken Islamist voters’ opposition against him.

Figures 7 and 8 approach the question from the perspective of party competition. Figure 7 plots the correlations between the number of pesantren and the vote share of Islamic parties in the 2019 parliamentary election. Counting only the United Development Party (PPP), the Prosperous Justice Party (PKS), and the Crescent Star Party (PBB) as Islamic parties, the correlation is a modest (r=.243). The higher the number of pesantren in a district, the higher the vote share of Islamic parties. Adding the National Mandate Party (PAN) and the National Awakening Party (PKB) strengthens this correlation. But even then, the correlation is not particularly strong, as the number of pesantren only explains about 13% of Islamic parties’ vote share.

Figure 8 breaks down the vote share of Islamic parties into individual party’s vote share. Given how pesantren are predominantly NU-affiliated, it is unsurprising that the correlation between pesantren and vote share is strongest for PKB, widely regarded as an NU-linked party. The correlation with PPP is also relatively unsurprising, considering it was the product of a fusion of Islamic parties in 1973 (including the former NU party) and has ties with traditional Muslims.

Perhaps the most surprising pattern from Figure 8 is the respectable correlation between pesantren and PKS’s vote share. As a party that grew out of student movements and urban Muslims, PKS is not generally associated with pesantren and their traditionalist Islamic networks. However, the modest correlation suggests that the party has successfully made inroads into pesantren-based and traditionalist Muslim voters.

My analysis provides background information about pesantren in Indonesia, offering new foundational empirical insights for systematically studying the social

Social media offers an ersatz form of accountability

Indonesia’s democracy is becoming reactive. Is that good?

Other findings are less intuitive, for example about how the predominance of NU pesantren varies across provinces and about how PKS’s vote share is quite strongly related to the number of pesantren in a district. These analyses are preliminary and relatively basic. As mentioned, without making any claims about the accuracy of this data, I have made the data available for public use at my website.

Combining this dataset with other available data on Indonesia, researchers may explore deeper questions about Indonesia’s political and religious landscape. For example, researchers may combine pesantren data with survey data to examine how pesantren density correlates with public opinion about the role of Islam in public affairs. Alternatively, researchers may also combine pesantren data with that which measures religious tolerance and examine how the two may be related. All of these exercises will help us understand the roles and significance of pesantren in shaping Indonesia’s social and political life.

The post The pesantren archipelago appeared first on New Mandala.

This post was originally published on New Mandala.

By Caleb Fotheringham, RNZ Pacific reporter

Four Papuan political prisoners have been sentenced to seven months’ imprisonment on treason charges.

But a West Papua independence advocate says Indonesia is using its law to silence opposition.

In April this year, letters were delivered to government institutions in Sorong West Papua, asking for peaceful dialogue between Indonesia’s President Prabowo Subianto and a group seeking to make West Papua independent of Indonesia, the Federal Republic of West Papua.

Four people were arrested for delivering the letters, and this triggered protests, which became violent.

West Papua Action Aotearoa’s Catherine Delahunty said Indonesia claims the four, known as the Sorong Four, caused instability.

“What actually caused instability was arresting people for delivering letters, and the Indonesians refused to acknowledge that actually people have a right to deliver letters,” she said.

“They have a right to have opinions, and they will continue to protest when those rights are systematically denied.”

Category of ‘treason’

Indonesia’s Embassy based in Wellington said the central government had been involved in the legal process, but the letters fell into the category of “treason” under the national crime code.

Delahunty said the arrests were in line with previous action the Indonesian government had taken in response to West Papua independence protests.

“This is the kind of use of an abuse of law that happens all the time in order to shut down any form of dissent and leadership. In the 1930s we would call this fascism. It is a military occupation using all the law to actually suppress the people.”

Delahunty said the situation was an abuse of human rights and it was happening less than an hour away from Darwin in northern Australia.

The spokesperson for Indonesia’s embassy said the government had been closely monitoring the case at arm’s length to avoid accusations of overreach.

This article is republished under a community partnership agreement with RNZ.

This post was originally published on Asia Pacific Report.

ANALYSIS: By Dr Muhammad Zulfikar Rakhmat

Indonesia is preparing one of the largest peacekeeping deployments in its history — a 20,000-strong force of soldiers, engineers, medics and logistics personnel — to enter the shattered and starving Gaza Strip.

Three brigades, three hospital ships, Hercules aircraft, a three-star general, a reconnaissance team, battalions for health services, construction and logistics — Jakarta is moving with remarkable speed and confidence.

But the moral clarity that Indonesia prides itself on in its support for Palestine is now in danger of being muddied by geopolitical calculation.

And that calculation, in this case, is deeply entangled with a plan conceived and promoted by US President Donald Trump — a plan that critics argue would freeze, not resolve, the structures of domination and blockade that have long suffocated Gaza.

Indonesia must ask itself a hard question: Is it stepping into Gaza to help Palestinians — or to help enforce a fragile order designed to protect the status quo?

For years, Indonesian leaders have proudly stated that their support for Palestine is grounded not in expediency but in principle.

President Prabowo Subianto has reiterated that Jakarta stands “ready at any moment” to help end the suffering in Gaza. But readiness is not the same as reflection. And reflection is urgently needed.

Tilted towards Israel

Trump’s so-called stabilisation plan envisions an International Stabilisation Force tasked with training select Palestinian police officers and preventing weapons smuggling — a mission framed as neutral but structurally tilted toward Israel’s long-standing security demands.

The plan does little to address the root political causes of Gaza’s devastation. It does not confront Israel’s decades-long military occupation.

It does not propose a just political horizon. And it does not establish meaningful accountability for continued violations, even as reports persist that ceasefire terms are repeatedly breached.

A peacekeeping force that does not address the underlying conditions of injustice is not peacekeeping. It is de facto enforcement of a deeply unequal arrangement.

Indonesia’s deployment risks becoming just that.

Former deputy foreign minister Dino Patti Djalal has urged caution, warning that Indonesian troops could easily be drawn into clashes simply because the territory remains saturated with weaponry, competing authorities and unresolved political tensions.

He argues that Indonesia must insist on crystal-clear rules of engagement. With volatility always a possibility, a mission built on ambiguity is a mission built on quicksand.

Impossible peacekeeper position

His warning deserves attention. A peacekeeper who does not know whether they are expected to intervene, withdraw or hold ground in moments of confrontation is placed in an impossible position.

And should Indonesian forces — admired worldwide for their professionalism — be forced to navigate chaos without a political framework, Jakarta will face unpredictable political and humanitarian consequences at home and abroad.

More troubling is the lack of political strategy behind Indonesia’s enthusiasm. Prabowo’s government frames this mission as a humanitarian and stabilising operation, but it has not clarified how it fits within the long-term political resolution that Indonesia claims to champion.

For decades, Jakarta has stood consistently behind a two-state solution. Yet today, after the destruction of Gaza and the collapse of any credible peace process, many Palestinians and international observers argue that the two-state paradigm has become a diplomatic mirage — repeatedly invoked, never realised, and often used to justify inaction.

If Indonesia truly wants to stand for justice rather than merely stability, it must be willing to articulate alternatives. One of those alternatives — controversial but increasingly discussed in academic, political and human rights circles — is a rights-based one-state solution that guarantees equal citizenship and security for all who live between the river and the sea.

Such a political horizon would require courage from Jakarta. Supporting a single state would mean breaking sharply from US policy preferences and acknowledging that decades of partition proposals have failed to deliver anything resembling peace.

But Indonesia has taken courageous positions before. It has spoken against apartheid in South Africa and, most recently, called out the global community’s double standards in the treatment of Ukraine and Palestine.

Jakarta must be moral voice

If Jakarta wants to be a moral voice, it cannot outsource its vision to a proposal drafted by an American administration whose approach to the conflict was widely criticised as one-sided.

Indonesia’s soldiers are being told they are going to Gaza to help. That is noble. But noble intentions do not excuse political naivety.

Before Jakarta sends even a single battalion forward — before the hospital ships are launched, before the Hercules engines warm, before the three-star commander takes his post — Indonesia must ask whether this mission will move Palestinians closer to genuine freedom or merely enforce a temporary calm that leaves the underlying injustices untouched.

A peacekeeping force that sustains the structures of oppression is not peacekeeping at all. It is maintenance.

Indonesia can — and must — do better.

Dr Muhammad Zulfikar Rakhmat is the director of the Indonesia-MENA Desk at the Centre for Economic and Law Studies (CELIOS) in Jakarta and a research affiliate at the Middle East Institute, National University of Singapore. He spent more than a decade living and traveling across the Middle East, earning a BA in international affairs from Qatar University. He later completed his MA in International Politics and PhD in politics at the University of Manchester. This article was first published by Middle East Monitor.

This post was originally published on Asia Pacific Report.

ANALYSIS: By Dr Muhammad Zulfikar Rakhmat

Indonesia is preparing one of the largest peacekeeping deployments in its history — a 20,000-strong force of soldiers, engineers, medics and logistics personnel — to enter the shattered and starving Gaza Strip.

Three brigades, three hospital ships, Hercules aircraft, a three-star general, a reconnaissance team, battalions for health services, construction and logistics — Jakarta is moving with remarkable speed and confidence.

But the moral clarity that Indonesia prides itself on in its support for Palestine is now in danger of being muddied by geopolitical calculation.

And that calculation, in this case, is deeply entangled with a plan conceived and promoted by US President Donald Trump — a plan that critics argue would freeze, not resolve, the structures of domination and blockade that have long suffocated Gaza.

Indonesia must ask itself a hard question: Is it stepping into Gaza to help Palestinians — or to help enforce a fragile order designed to protect the status quo?

For years, Indonesian leaders have proudly stated that their support for Palestine is grounded not in expediency but in principle.

President Prabowo Subianto has reiterated that Jakarta stands “ready at any moment” to help end the suffering in Gaza. But readiness is not the same as reflection. And reflection is urgently needed.

Tilted towards Israel

Trump’s so-called stabilisation plan envisions an International Stabilisation Force tasked with training select Palestinian police officers and preventing weapons smuggling — a mission framed as neutral but structurally tilted toward Israel’s long-standing security demands.

The plan does little to address the root political causes of Gaza’s devastation. It does not confront Israel’s decades-long military occupation.

It does not propose a just political horizon. And it does not establish meaningful accountability for continued violations, even as reports persist that ceasefire terms are repeatedly breached.

A peacekeeping force that does not address the underlying conditions of injustice is not peacekeeping. It is de facto enforcement of a deeply unequal arrangement.

Indonesia’s deployment risks becoming just that.

Former deputy foreign minister Dino Patti Djalal has urged caution, warning that Indonesian troops could easily be drawn into clashes simply because the territory remains saturated with weaponry, competing authorities and unresolved political tensions.

He argues that Indonesia must insist on crystal-clear rules of engagement. With volatility always a possibility, a mission built on ambiguity is a mission built on quicksand.

Impossible peacekeeper position

His warning deserves attention. A peacekeeper who does not know whether they are expected to intervene, withdraw or hold ground in moments of confrontation is placed in an impossible position.

And should Indonesian forces — admired worldwide for their professionalism — be forced to navigate chaos without a political framework, Jakarta will face unpredictable political and humanitarian consequences at home and abroad.

More troubling is the lack of political strategy behind Indonesia’s enthusiasm. Prabowo’s government frames this mission as a humanitarian and stabilising operation, but it has not clarified how it fits within the long-term political resolution that Indonesia claims to champion.

For decades, Jakarta has stood consistently behind a two-state solution. Yet today, after the destruction of Gaza and the collapse of any credible peace process, many Palestinians and international observers argue that the two-state paradigm has become a diplomatic mirage — repeatedly invoked, never realised, and often used to justify inaction.

If Indonesia truly wants to stand for justice rather than merely stability, it must be willing to articulate alternatives. One of those alternatives — controversial but increasingly discussed in academic, political and human rights circles — is a rights-based one-state solution that guarantees equal citizenship and security for all who live between the river and the sea.

Such a political horizon would require courage from Jakarta. Supporting a single state would mean breaking sharply from US policy preferences and acknowledging that decades of partition proposals have failed to deliver anything resembling peace.

But Indonesia has taken courageous positions before. It has spoken against apartheid in South Africa and, most recently, called out the global community’s double standards in the treatment of Ukraine and Palestine.

Jakarta must be moral voice

If Jakarta wants to be a moral voice, it cannot outsource its vision to a proposal drafted by an American administration whose approach to the conflict was widely criticised as one-sided.

Indonesia’s soldiers are being told they are going to Gaza to help. That is noble. But noble intentions do not excuse political naivety.

Before Jakarta sends even a single battalion forward — before the hospital ships are launched, before the Hercules engines warm, before the three-star commander takes his post — Indonesia must ask whether this mission will move Palestinians closer to genuine freedom or merely enforce a temporary calm that leaves the underlying injustices untouched.

A peacekeeping force that sustains the structures of oppression is not peacekeeping at all. It is maintenance.

Indonesia can — and must — do better.

Dr Muhammad Zulfikar Rakhmat is the director of the Indonesia-MENA Desk at the Centre for Economic and Law Studies (CELIOS) in Jakarta and a research affiliate at the Middle East Institute, National University of Singapore. He spent more than a decade living and traveling across the Middle East, earning a BA in international affairs from Qatar University. He later completed his MA in International Politics and PhD in politics at the University of Manchester. This article was first published by Middle East Monitor.

This post was originally published on Asia Pacific Report.

Asia Pacific Report

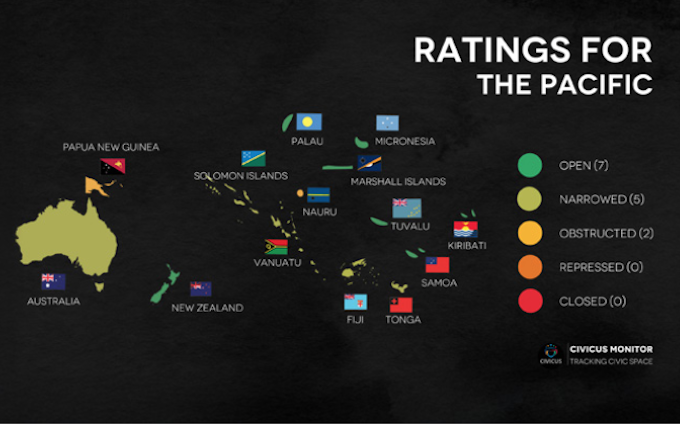

The global civil society alliance Civicus has called on eight Pacific governments to do more to respect civic freedoms and strengthen institutions to protect these rights.

It is especially concerned over the threats to press freedom, the use of laws to criminalise online expression, and failure to establish national human rights institutions or ratify the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR).

But it also says that the Pacific status is generally positive.

Nauru, Papua New Guinea, Samoa and Solomon Islands have been singled out for criticism over press freedom concerns, but the brief published by the Civicus Monitor also examines the civic spce in Fiji, Kiribati, Tonga and Vanuatu.

“There have been incidents of harassment, intimidation and dismissal of journalists in retaliation for their work,” the report said.

“Cases of censorship have also been reported, along with denial of access, exclusion of journalists from government events and refusal of visas to foreign journalists.”

The Civicus report focuses on respect for and limitations to the freedoms of association, expression and peaceful assembly, which are fundamental to the exercise of civic rights.

Freedoms guaranteed