Two examples — Korea and Indonesia — will be documented here in order to display that America’s Cold War against communism was/is a cover-story, or deceptive cloak, for a war actually against the poor (and the political Left) in all nations: in other words, a fascist war, meaning that America’s Government became fascist-imperialist as soon as World War II ended, despite FDR (Franklin Delano Roosevelt — America’s President throughout WW II) having been passionately anti-fascist and anti-imperialist. All of this will be explained here, and documented in the article’s links. First, however, will be explained the underlying economic mechanism employed by means of this war that’s actually against the poor, not ONLY against communists. This modern version of fascist-imperialism relies more on deception — on sophisticated propaganda — than Hitler’s did, because Hitler never pretended to advocate for democracy, whereas America does. So, here it is:

In third-world countries, where labor is non-unionized and cheap, an international corporation can supply the latest industrial machinery, to be worked by the fewest dirt-wage workers in order to undercut the prices of any merely intranational (or ‘local’) corporation while still making intranational (within-nation) profits that are vastly higher than any merely local corporations (which are competing against the multinational ones) in any country can and do; and this is the secret of billionaires (who control international corporations) by which they consequently generate vastly higher rates of return on investment than any merely local entrepreneurs possibly can. Offshoring production thus greatly increases return-on-investment for the billionaires while it drives wages down for the workers in the industrialized countries. On a global scale, it’s a war by the super-rich against the poor. In both respects (by lowering wages in industrialized countries and prohibiting labor unions in the banana republics), the result is to cause an ever-increasing proportion of the world’s wealth to become concentrated amongst the billionaires — the people who control international corporations. From the standpoint of billionaires, it’s the system that surpasses any other. From the standpoint of the world’s poor, however, it is the worst system imaginable, because it funnels wealth from the masses to the super-rich; it impoverishes billions while pouring a bigger and bigger share of the world’s wealth into the control of the world’s mere 3,000-or-so billionaires. That’s the way the world works and ever-increasingly has worked ever since 1945.

Here’s how it happened:

Korea

“The secret genocide in South Korea you’ve probably never heard of”

(The sources in the article, by Écspielle Kay, excerpted here are mainly hidden behind paywalls because the U.S. Government has always suppressed what this article is reporting. But I have accessed every source here, and find the article to be fully honest and accurately documented. I have removed the photos but retain their descriptions.)

… What had really happened in Daejeon in the summer of 1950 … was later termed the Bodo League massacre.

The centre of Daejeon, South Korea, appearing as an ordinary industrial city. Also the site of one of history’s largest massacres.

Song Joon-ae immediately told the manager of the site. The manager of the site called the Daejeon division of the construction contractor company. It continued upwards until the discovery was brought to the attention to South Korean authorities. The construction site became an excavation site, and the bones which Soon Joon-ae found were not the last to be unearthed.

Government officials at the various sites around Daejeon found hundreds of sites with hundreds of bodies, some children, some infants, some civilians, some wearing peasant clothing, others wearing military uniform. Park Rae-mun, an archaeologist who appeared at the site estimated that 1.2 million people were massacred at the various sites around Daejeon. Kim Dong-Choon of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, a South Korean governmental body, conservatively estimates that approximately 100,000 were executed by the South Korean military on October 1950, while many point to 400,000 as a likely figure. Both executioners and escapees came forward, and a picture gradually built up that these people were massacred on the suspicion of being leftists. …

The story of South Korea’s past starts with a provisional government often forgotten about in history textbooks. The People’s Republic of Korea lasted only from 1945 to 1946, and its capital was in Seoul. Through people’s committees all over the Korean peninsula, a twenty-seven-point programme was formed through democratic participation in government, a relatively novel experience for Korean people at the time.

“the confiscation without compensation of lands held by the Japanese and collaborators; free distribution of that land to the peasants; rent limits on the non-redistributed land; nationalization of such major industries as mining, transportation, banking, and communication; state supervision of small and mid-sized companies; …guaranteed basic human rights and freedoms, including those of speech, press, assembly, and faith; universal suffrage to adults over the age of eighteen; equality for women; labor law reforms including an eight-hour day, a minimum wage, and prohibition of child labor; and “establishment of close relations with the United States, USSR, England (ed. should be the United Kingdom), and China, and positive opposition to any foreign influences interfering with the domestic affairs of the state.”…

As soon as American troops landed in September of 1945, something seemed off about the People’s Republic of Korea. Nationalisation of major industries? Free distribution of land to peasants? People’s committees? Strong labour-unions and an eight-hour work day? To the United States, this experiment in a united Korean peninsula under democratic rule whiffed of communism.

What immediately occurred afterwards was the abolition of the People’s Republic of Korea by military decree. Officials serving under the government were shot, buildings were bombed, and supposedly “communist-sympathetic” Korean troops stationed in the country were summarily executed in a bloodbath lasting for several months. The United States Army Military Government was established, causing the eruption of mass public outrage at military personnel from the former Japanese Empire serving in office in South Korea.

To even further outrage, Lieutenant General John R. Hodge of the 24 Corps of the U.S. Tenth Army, assessing the situation badly, announced that the Japanese colonial government in Incheon would be kept, and, surprised at the poor reaction from Korean citizens his decision had elicited, tried to placate them by creating the Korean Advisory Council to represent the voice of ordinary Koreans. Unsurprisingly, his council was composed of landowners, wealthy businessmen, and officials from the Japanese colonial government.

Still not taking the hint, the military government continued to rule over months of civil unrest and outbursts of violence after outlawing the people’s committees and the PRK government. On September 23, 1946, 8,000 railway workers in Busan lead a strike, quickly spreading to hundreds of other towns and cities. A police station in Yeongcheon went under siege as a crowd numbering in the tens of thousands converged all at once, killing 40 policemen. More rebellions killed more than 20 Japanese officials and landlords. The situation escalated, and the American military declared martial law, tens of thousands being killed as military troops fired into mass crowds of demonstrators.

With haste, the First Republic of Korea, what we now know as South Korea, was declared in 1948. Syngman Rhee was flown abroad a US military aircraft to Tokyo, travelling to Seoul, and was installed as [president of the First Republic of Korea]. Rhee immediately arrested the remaining left-wing opponents in the political arena, setting his sights on Kim Koo, a former independence activist, an increasingly popular statesman, and advocate of unification. Syngman Rhee, as a fierce anti-communist and nationalist who would later be forced into exile by his own citizens, had him killed on 26 June 1949. …

*****

“South Korea’s Embattled Truth and Reconciliation Commission,” 1 March 2010

MS [Mark Selden]: How have the media covered the work of the Commission?

KDC [Kim Dong-chun, retired Standing Commissioner of South Korea’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission]: We have had to contend with the fact that the biggest Korean newspapers have ignored or suppressed our important findings and resolutions. The conservative press fails to recognize the relationship between past wrongs and present injustices facing many Korean citizens and those of other countries.

*****

“The Road to the Truth: Lessons from South Korea’s Truth Commissions” (2021)

1 The Final Report of the Jeju Commission confirmed systemic massacres, indiscriminate arrests, torture, and summary executions by the Rhee government during the U.S. military occupation of Korea. 72 The release of the Final Report in 2003 resulted in a public apology from then President Roh Moo-hyun, the inclusion of the Final Report in Korea’s educational curriculum, and the creation of memorials for the deceased.73 Unlike the Anti-Nation Commission, the Jeju Commission had a clear mandate that authorized the Jeju Commission to freely conduct investigations into the Jeju Uprising.74 The extensive involvement of the Office of the Prime Minister also showed how proper governmental support helped the Jeju Commission succeed.75 The apology from President Roh was particularly significant because it marked the first apology by a head of state for human rights abuses in Korea.76 Furthermore, the allowance of the Final Report in high school classrooms allowed for a more neutral understanding of what really happened in the period leading up to the Korean War.77 C. South Korean Truth Commissions and the Korean War The Korean War claimed the lives of over 1,000,000 civilians, which made it the deadliest civilian event in Korean history.78 During the Korean war, atrocities were committed by the South Korean government against its own citizens. 79 For example, the 1949 Bodo League massacres that occurred during the Rhee presidency claimed the lives of nearly 200,000 South Koreans for allegedly being North Korean spies or communist sympathizers. 80 …

Although the TRCK made efforts to locate remains from mass graves related to the Bodo League Massacres and the Geochang massacres, the TRCK’s efforts were cut short due to an abrupt change in leadership in 2008, when President Lee Myung-bak came to power.89 When established in 2005, the TRCK had the full support of then President Roh Moo-hyun who was committed to using truth commissions as a vehicle for uncovering the violent truths of Korea’s past.90 In contrast, President Lee saw truth commissions as an obstacle to his goal of bolstering Korea’s economy.91 The TRCK’s resources and mandate became even more vulnerable when Lee appointed “new leaders” to the TRCK commission to better serve his policy agendas.92

*****

“The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Korea: Uncovering the Hidden Korean War”

1 March 2010, by Kim Dong-choon

The Other War: Korean War Massacres

More than 2 million people were killed during the Korean War. The casualties included not only military personnel but also innocent civilians. Few are aware that the Korean authorities as well as US and allied forces massacred hundreds of thousands of South Korean civilians at the dawn of the Korean War on June 25, 1950. The official records of government, military and police, as well as survivor testimonies, reveal that mass killings committed by South Korean and U.N forces occurred before and during the Korean War (June 1950 to July 1953).

*****

“Truman put Nukes in Guam and Gave the Order to Nuke North Korea”

(Based upon key details that slipped through in the academic book by Bruce Cumings; (2011) The Korean War, Robert Barsocchini documents that President Truman had an order drawn up to nuke North Korea but, for some unclear reason, “the order [to nuke North Korea] was never sent.” This was already after Truman had –)

managed to kill millions of Koreans, many, if not most, with “oceans” of napalm produced largely by the Dow Chemical Company, which the US air-force “loved”, referring to it as the “wonder weapon” for its ability to wipe out whole cities of people.

One day Pfc. James Ransome, Jr.’s unit suffered a “friendly” hit of this wonder weapon: his men rolled in the snow in agony and begged him to shoot them, as their skin burned to a crisp and peeled back “like fried potato chips.” Reporters saw case after case of civilians drenched in napalm — the whole body “covered with a hard, black crust sprinkled with yellow pus.”

US “intent was to destroy Korean society down to the individual constituent”.

Cities were destroyed, civilians burned to death and blown to bits with zero “tactical or strategic value”. Killing was an “end in itself”.

“[T]he United States Air Force was inflicting genocide”, Cumings notes, “on the citizens of North Korea.”

*****

“The Case Against North Korea”

(I had posted this on 23 September 2019, to place into historical perspective the U.S. regime’s war against North Korea:)

So, Iran didn’t ever invade America, nor did Russia. What about North Korea, then? Did North Korea ever invade America? No, neither did that alleged ‘enemy’ of America. But America did invade North Korea during the Korean War. Have you ever seen the 764-page “Report of the International Scientific Commission for the Investigation of the Facts Concerning Bacterial Warfare in Korea and China”? It documents America’s biological warfare program against North Korea in 1952. You probably haven’t even heard about it, because the U.S. regime managed to keep it hidden from the public until just this year, and because America’s ‘news’-media continue to blacklist its existence so as to continue the ‘justification’ for the U.S. regime’s still-ongoing efforts to conquer North Korea. But look at it here, as soon as its 764 pages have finished loading into your computer. Now that the U.S. regime is increasing its threats against both North Korea and China, the Governments in those countries recently released this document to the public, and thereby are challenging the U.S. propaganda-media to allow the publics in the U.S. and its vassal nations to see it — to see real history about this matter, not just propaganda (such as the U.S. is the world’s champion of).

This massive historical document opens:

On the 22nd. Feb. 1952, Mr. Bak Hun-Yung, Foreign Minister of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, and on the 8th. March, Mr. Chou En-Lai, Foreign Minister of the People’s Republic of China, protested officially against the use of bacteriological warfare by the U.S.A. On the 25th. Feb., Dr. Kuo Mo-Jo, President of the Chinese People’s Committee for World Peace, addressed an appeal to the World Peace Council.

At the meeting of the Executive Committee of the World Peace Council held at Oslo on the 29th. March, Dr. Kuo Mo-Jo, with the assistance of the Chinese delegates who accompanied him, and in the presence of the Korean representative, Mr. Li Ki-len, placed the members of the Committee, and other national delegates, in possession of much information concerning the phenomena in question. Dr. Kuo declared that the governments of China and (North) Korea did not consider the International Red Cross Committee sufficiently free from political influence to be capable of instituting an unbiassed enquiry in the field. This objection was later extended to the World Health Organisation, as a specialised agency of the United Nations. However, the two governments were entirely desirous of inviting an international group of impartial and independent scientists to proceed to China and to investigate personally the facts on which the allegations were based. They might or might not be connected with organisations working for peace, but they would naturally be persons known for their devotion to humanitarian causes. The group would have the mission of verifying or invalidating the allegations. After thorough discussion, the Executive Committee adopted unanimously a resolution calling for the formation of such an International Scientific Commission.

Ultimately, as Jeffrey S. Kay recently explained in his superb article at Global Research introducing this document to U.S.-and-allied publics:

Written largely by the most prestigious British scientist of his day, this report was effectively suppressed upon its release in 1952. Published now in text-searchable format, it includes hundreds of pages of evidence about the use of U.S. biological weapons during the Korean War, available for the first time to the general public.

Back in the early 1950s, the U.S. conducted a furious bombing campaign during the Korean War, dropping hundreds of thousands of tons of ordnance, much of it napalm, on North Korea. The bombardment, worse than any country had received up to that point, excepting the effects on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, wiped out nearly every city in North Korea, contributing to well over a million civilian deaths. Because of the relentless bombing, the people were reduced to living in tunnels. Even the normally bellicose Gen. MacArthur claimed to find the devastation wreaked by the U.S. to be sickening.[1]

The massive document itself authenticates numerous reports of the U.S. flying planes over North Korea and dropping containers of fleas, clams, and other creatures, that were tested and verified as being contaminated with plague and cholera. For example, on pages 24-26 are described several such incidents. Typical was one in which “the Commission had no option but to conclude that the American air force was employing in Korea methods very similar to, if not exactly identical with, those employed to spread plague by the Japanese during the second world war.” Furthermore, one expert “gave evidence to the effect that he had urged the Kuomintang government to make known to the world the facts concerning Japanese bacterial warfare, but without success, partly, he thought, as the result of American dissuasion.” In other words: the U.S. regime not only protected and hired ‘former’ Nazis to use against USSR, but it did the same with Japan to use against China and North Korea. This 1952 operation against North Korea was perpetrated by the regime under U.S. President Harry S. Truman — the former Vice President who had been forced onto FDR’s final ticket by that Party’s top donors in order to get a war started against the Soviet Union and thereby keep their enormous government contracts continuing after WW II. Right after FDR died, Truman got fooled by Churchill and Eisenhower into starting the Cold War against the Soviet Union; and this 1952 international war-crime against China and North Korea was part of that.

(The Netflix series from South Korea, The Glory, is fictional but its portrayal of current South Korean culture is relevant here because it portrays South Korea as having a rigid and brutal caste-system that honors the rich and damns the poor, and thus it exemplifies in today’s generation of South Koreans the values-system that the U.S. regime has inculcated into their culture. This is an extreme version of neoliberalism-libertarianism, a zero-sum-game view of life in which individuals are evaluated mainly if not entirely by how wealthy or poor they are: rights come ONLY from wealth, and the poor are worth nothing and deserve to be trashed.)

*****

Indonesia

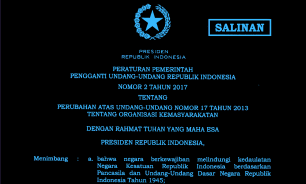

The October 1965 through March 1966 Indonesian government extermination of anywhere from 500,000 to two million Indonesian supporters of communism and of any other left-wing (or pro-poor) political party — including supporters of Indonesia’s leader, General Sukarno, who had some leftist supporters, including some that were communists — was probably masterminded, ordered, by U.S. President Lyndon Johnson, on behalf of the owners of the mega-corporations who were backing the Democratic Party. Certainly, LBJ was behind this ‘ethnic cleansing’, even well before it began. As early as March 1965, Johnson’s people were privately vitriolic against Sukarno, who was making noises about land-reform and possibly nationalizing natural resources. For example, on 18 March 1965, “118. Memorandum From the Under Secretary of State (Ball) to President Johnson” opened:

Our relations with Indonesia are on the verge of falling apart. Sukarno is turning more and more toward the Communist PKI. The Army, which has been the traditional countervailing force, has its own problems of internal cohesion. Within the past few days the situation has grown increasingly more ominous. Not only has the management of the American rubber plants been taken over, but there are dangers of an imminent seizure of the American oil companies.

The coup started on 1 October 1965; General Suharto was installed to replace Sukarno, and promptly began the extermination-campaign. But he didn’t know whom to slaughter; so, as one excellent review of Vincent Bevins’s excellent book about the slaughters, The Jakarta Method: Washington’s Anticommunist Crusade and the Mass Murder Program that Shaped Our World, succinctly put the matter, “The US provided arms, training, communication equipment and lists of thousands of real and alleged leftists to be killed. US-owned plantations furnished lists of ‘troublesome’ employees. US officials repeatedly sent cables to the leader of the butchery, General Suharto, to kill the leftists faster.” Other fine reviews of this book are here and here. However, like the other books that have been published about that extermination-campaign, Bevins’s focus isn’t on the masterminds who planned and bribed to get it done (its beneficiaries), but instead on the physical perpetrators and their victims. The coup-and-extermination’s ultimate beneficiaries aren’t named, nor identified.

The U.S. did that extermination in conjunction with other members of the American gang, mainly in Europe. The Judge in the International People’s Tribunal stated that “the United States of America, the United Kingdom and Australia were all complicit to differing degrees in the commission of these crimes against humanity.” It was a Rhodesist operation, done for the U.S.-and-allied (especially Netherlands) aristocracies.

As I have documented elsewhere, FDR was intensely opposed to all imperialisms, but on 25 July 1945, Truman made the decision to reverse FDR’s foreign policies and aim for the U.S. itself to take control over the entire world.

(The 1982 Peter Weir movie, The Year of Living Dangerously, dramatically represents, from the standpoints of diplomats who were serving in Indonesia at the time leading up to and during the extermination-campaign, the chaotic conditions in Indonesia during that period, but sheds little light upon the reasons, methods, perpetrators, and beneficiaries, behind the massacres.)

The post America’s “War against Communism” Was Really a War against Advocates for the Poor first appeared on Dissident Voice.