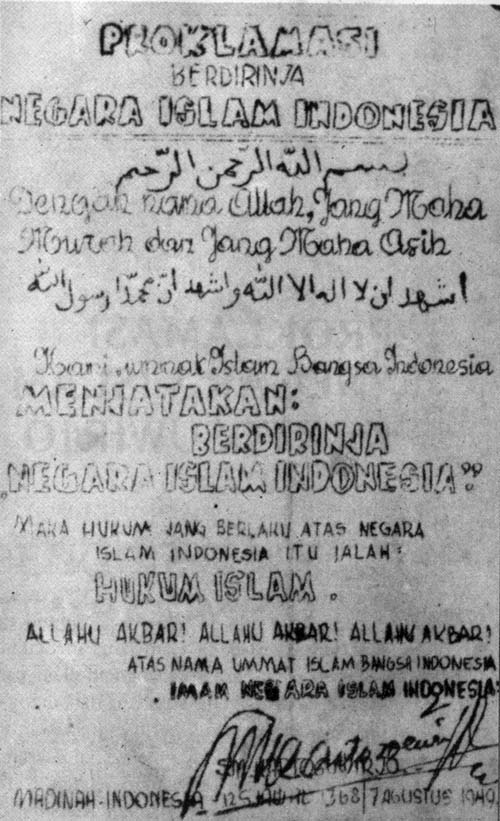

The reports of anxiety and fear as the Taliban marched through to claim rule in Afghanistan and the crescendo of reports of the targeting of women has invoked memories of stories people told me about living under the rule of Kahar Muzakkar’s Darul Islam/Tentara Islam (henceforth DI/TI) in South Sulawesi. This fraction of Indonesia’s post-colonial Islamic state movement, first established by Kartosuwirjo in West Java in the 1950s, held power over much of rural South Sulawesi (including what is now Southeast Sulawesi Province) until the early 1960s. My doctoral research on Sorowako, in the northern mountains of South Sulawesi, concerned the social and economic impacts of a foreign-owned nickel mine that had just been opened by President Suharto. I arrived in 1978, and the local population were still smarting from the forced loss of their land and livelihoods. But when I sat down to yarn with people, they were compelled to tell me also about their suffering under what they termed the ‘gerombolan’ (‘gang’). This area had been close to one of the key centres of Kahar’s movement (Kolaka in Sulawesi Tenggara): the rebel troops had forcibly moved the people from the western shore of Lake Matano, the end point of the road to Malili on the coast, to a remote location on the wild side of the lake—which the people termed the penyingkiran (evacuation site). They explained to me that the guerrilla fighters wanted to ensure local populations could not be forced to provide sustenance to the guerrillas’ enemy, the Indonesian army (TNI) troops. Local people’s accounts of DI/TI, who lived among them exercising authority and control for over a decade, always feature stories about actions that are harsh, even cruel.

Islam in Sorowako

The ‘orang asli Sorowako,‘ as they called themselves, had been Islamised by functionaries from the Kerajaan Luwu deployed as colonial officials by the Dutch after they extended direct control over the interior regions of Sulawesi’s southwestern peninsular around 1906. From the early 1950s DI/TI forcibly Islamised Christian villagers around Lake Matano who had been relocated there from further up the mountains. Villages and ripening fields on the lake shore were burned as people were forced to flee.

Life in the jungle refuge was full of privation, and over the years I learned about the ways the DI/TI impacted on individual lives. The current stories of young Afghani women being forcibly married to Taliban fighters, or people hiding their daughters as the fighters rolled into their towns brought to mind the personal stories of forced marriages to DI/TI fighters recounted by many of my friends in Sorowako. One very independent woman raising her now adult (disabled) son on her own had been forcibly married in this manner. I asked a family member if the marriage lasted after the cease fire with government troops in 1962. I was told: ‘she pushed the stairs away from the (stilt) house’ i.e. a strong message to the husband ‘don’t come back’. People gossiped about a ‘wrong marriage’ of a friend: wrong according to the rules of the bilateral kinship system which stressess generational relations. Prior to their marriage he had called her ‘aunt’—that is she was the generation above him, not on ‘cousin’ level. Her father, a village leader, married her off quickly to avoid her forcible marriage to a DI/TI soldier. No doubt many of these marriages were polygynous, both within the DI/TI -controlled territory and in their home villages, and this alone would have given parents reason to fear them. Collecting genealogies, I came across quite a few men who had been DI/TI fighters. The charismatic rebel leader Kahar was himself polygynous (practiced poligami) having 9, or some accounts say 12, wives—and this excessive sexuality was an aspect of his hyper-masculinised charisma.

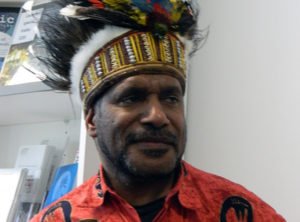

Photo of Kahar Muzakkar, the leader of the Sulawesi rebellion from 1950-1965. KamielahK on Wikicommons

There were many stories of kidnapping, especially people from the government-controlled towns who had expertise the rebels desired—such as accountants, teachers and agricultural experts—to set up their alternative administration. Government was in accord with a document establishing shariah law as the basis of the Makalua charter. It contained provisions, similar to that of the Taliban, based on misogynistic readings of Islamic texts, on the fikih (Islamic jurisprudence) that supported a God-ordained male privilege. Women were forced to wear head coverings and live basically domestic lives. The Makalua charter allowed forced polygyny (poligami), indeed people who rejected polygyny could be prosecuted, and no offer of marriage could be refused, save that the man was a juvenile, impotent, diseased or of bad character. It had harsh provisions for regulating relations between the sexes, and a broad interpretation of zina (sexual acts outside marriage): I heard personal accounts from people who witnessed women accused of adultery being buried to the waist and stoned to death (dirajam). Other people graphically gestured to describe the practice of cutting off hands as punishment for theft.

Kahar has been described as a Muslim socialist and his rule also expressed a kind of ‘radical egalitarianism’ in that he sought to stamp out the power of Bugis nobility and the cultural trappings of their authority, which were an exercise of power that the pre-Islamic religion deemed ordained by the Gods of the Upper world. The corpus of pre-Islamic beliefs and rituals that validated social hierarchy and noble privilege and power and were divinely ordained and ritual life harkened back to the sacred cycle, La Galigo. DI/TI troops burned the houses of the nobility that symbolically encoded their status, and which housed sacred regalia. They banned syncretic ritual practices, melded with Islamic rituals for birth, death, marriage and activities such as farming and house construction. People of noble birth were targeted. A very confident Bugis noble woman form Malili told me she had been kidnapped as a 10 year- old child and held captive in the jungle ‘sleeping under the trees’ for three years. She recounted that she continuously scolded her captors and refused to bend to their world view. Just a few years ago, a friend who was in a ‘nostalgic’ mode told a story of seeing a DI/TI rebel walk up the stairs of a house and shoot the owner in his doorway, According to her, this was because they were of noble birth.

What allowed for despotism and misogynistic tyranny?

What makes this possible? Kahar’s rule over the Islamic state that he proclaimed relied on the Makalua charter, which was ostensibly based on the fikih: their understanding of Islamic law and what they believed to be Syariah. The elevation of a version of Islamic law (understood as God’s law and so not subject to debate) justified cruel summary justice. The Makalua charter and the ideology that it was the direct interpretation of the words of God justified this arbitrary behaviour, including the cruel and arbitrary treatment of women, and notably, control of their sexuality and public movement. This style of textual interpretation that the DI/TI and Taliban share is known in Indonesian as ‘Islam garis keras (hard-line Islam’). Former president and head of NU, Abdurahman Wahid (Gus Dur) reminded us that while the Qu’ran is the word of God it is always known through human interpretation—and scholars of Islam in the many educational institutions throughout Indonesia delight in textual debate

The people of Sorowako are today very observant Muslims, and acknowledge that the years under DI/TI rule led them to intensify their piety. A common view was that although they professed Islam by the 1950s, they had not been very pious. The threshold for conversion had been very low in South Sulawesi: recite the shahada, renounce eating pork and get circumcised. When I asked whether they supported the rebels, many people responded: yes, because it championed the elevation of Islam. Many are well-educated, working for the mining company or in other middle-class occupations, and their modernist and tolerant mode of Islamic practice is of the kind common to Indonesia’s urban middle classes. The village imam stressed an important point, from their contemporary understanding of piety. He said that the DI/TI compelled women to wear head covering: the women today, including young women, all wear head-covering (jilbab), but now it has more meaning as they do it from their own religious knowledge.

Memory activism—why not DI/TI?

The DI/TI came soon after the very traumatic events of the Japanese occupation, which is remembered as very brutal in this area. It also followed the 1947 Westerling massacres of the anti-colonial struggle. Memory activism is a notable political movement in in contemporary Indonesia, much of it focussing on the brutal mass killings of accused communists in 1965-6, associated with the power struggle that resulted in Suharto assuming the presidency. After his fall in 1998, memories of the suffering and lingering claims of injustice rapidly surfaced, especially among local populations (and especially in East Java) with remembrance of unmasked mass graves and slaughter sites serving as mnemonic devices to keep those memories alive. In Sorowako memories of the years of suffering under DI/TI go very deep and have not been supplanted by the more recent traumatic memories of the loss of their land and livelihoods under the Suharto regime’s foreign investment provisions. They do, however, acknowledge that the discourse of the threat of communism that was deployed by the New Order as a form of social and political control constrained their courage to oppose their dispossession to make way for the foreign-owned mine. A group of young people are now exploring the history of their community, including its’ history and culture before the development of the project and its associated suffering. They reported the same experience that I did when I asked about the past: the old people wish to recount their suffering under DI/TI.

The loyalty of some Islamist groups to AQ, and by extension, the Taliban, is evident from the content posted on their respective affiliated websites and publications.

Taliban rule restored in Afghanistan: security implications for Indonesia

The failure to address the events of the DI/TI years continue to have political consequences today. A descendant of Kahar Muzakkar has won political office, for example, on platforms that echo some of the tenets of Kahar’s movement and calling on the deceased Kahar’s enduring charisma. In the case of Sorowako the Christian Karongsi’e, who prior to the 1950s lived in a neighbouring village on the shores of Lake Matano, began to return to the mining town that had grown up on the shores of the lake. Their village had been burned at the same time as Sorowako and they had been forcibly Islamised and taken to the refuge site (so as not to provide assistance to government troops). In around 1960 they had been rescued from the penyingkiran (evacuation site) by the TNI (Indonesian army) and taken to Malili. From there they dispersed into Central Sulawesi—and were fearful to return until after Reformasi. They trickled back and established a settlement (considered illegal by the local government and the mining company) and pressed claims for compensation for their lands, forcibly abandoned during the DI/TI period and now incorporated into the mine concession area (used for residences and a golf course). The land ‘compensation’ has been controversial since the 1970s, but the company considers the process complete with the group who self-identify as the orang asli Sorowako, who are Muslim. They have had difficulty gaining formal recognition of their claims to indigeneity and for consequent privileges in the mining community.

The Karongsi’e who have come back since 1998 argue that they have been dispossessed by the mining development and their claims have been taken up by international and national NGOs who support their status as the indigenous people in East Luwu. These claims are accepted by the current local government. A 2016 report of KOMNASHAM (Indonesian Commission in Human Rights) on’ indigenous people in forest areas’ focused on the Karongsi’e to the exclusion of the orang asli Sorowako (even though the groups are linked through kinship and marriage, language and shared history in the pre-colonial and colonial eras). The erroneous description in that report draws on accounts of the historical experience of the orang asli Sorowako at the hands of the mining company, confusingly attributing this experience to Karongsi’e. Significantly, it fails to account for their fundamental dispossession by the DI/TI. They are represented as dispossessed by the mining development. The KOMNASHAM report follows the ‘script’ set out by the AMAN (Aliansi Masyarakat Adat Nusantara, the principle advocacy group for customary rights), which calls for ‘inventorising’ claims, including mapping graves. The identity of Karongsi’e as Christian is downplayed as adherence to a world religion does not fit the AMAN script. Meanwhile, the people of Sorowako regularly travel back to the cemetery at the penyingkiran, to clean graves before important Islamic holidays. There are a lot of graves, many of babies and children. Like people in areas of political killings in 1964-5, the act of clearing their loved ones’ graves triggers the memories of the years of suffering under DI/TII rule.

But the violence of the DI/TI which occurred in South and Southeast Sulawesi (and linked movements in West Java and Aceh), a quotidian occurrence over around 15 years, have not been the subject of contemporary memory activism. Perhaps current political sensitivities around political Islam preclude addressing the trauma of those years. But reports from Afghanistan and contemporary memory activism teach us that memories of trauma run deep, as I and others have found among the Sulawesi survivors of DI/TI.

The author has published extensively on this topic over many decades. Not all that scholarship has been digitised yet, so we encourage readers to seek out, in particular, her 1983 journal article “Living in the hutan: jungle village life under the Darul Islam” Review of Indonesian and Malaysian Affairs, vol 17. pp. 208-229. Professor Robinson has also recently published Mosques and Imams: Everyday Islam in Eastern Indonesia (2020) Singapore: NUS press.

The post Invoking memories of Darul Islam appeared first on New Mandala.

This post was originally published on New Mandala.