A year after our NM article about the impact of COVID-19 mitigation measures on Sumba we have an update. The main conclusions of our brief check in East Sumba last year in May was that there were very few COVID-19 infections, that people were more worried about harvest failure than about getting the virus, and that the local economy suffered from the lock down measures because market demand for products had collapsed.

We’ve closely followed developments since then, and in July 2021 the second author checked on the villages we studied in 2017 for our research on household vulnerability, poverty and the impact of social protection programs in Indonesia. What are the effects of the current crisis on the villagers? From their stories about the last year, we realised that the COVID-19 pandemic and mitigating measures were not the only crisis. Rather, four disasters occurred simultaneously. As well as COVID-19, a cyclone and animal diseases have hit the island, and a plantation expansion continues to threaten subsistence farmers’ livelihoods. The mix of all these disasters is leading to a decrease in the communities’ resource basis on which their resilience depends, but also had some surprisingly positive results. For example, where one family lost everything when the floods following the cyclone washed away their house and the crops in their riverbank garden, another family had a good year because excessive rain allowed a second crop of rice.

Community resource base

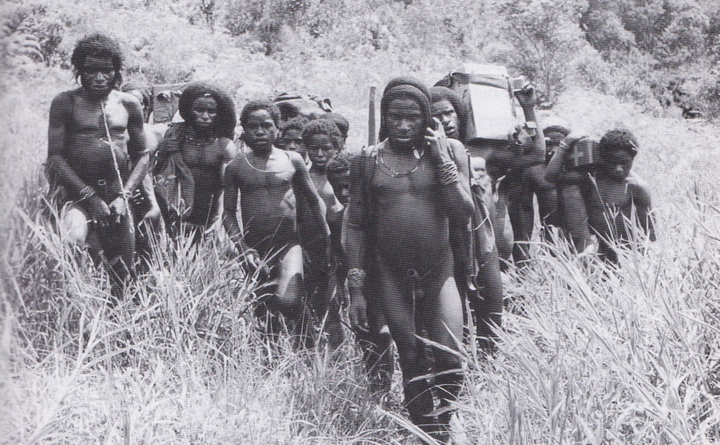

News stories about effects of disasters often show what happened to an individual or household. However, in Sumba the impact of disasters is very much a community matter. Sumba has a specific community economy, in which mutual assistance between members of lineage communities is a strong mechanism for coping with crisis. Local society has an economic class divide with a top layer consisting of government officials, businessmen, and local leaders who are well connected to government and business. Their spouses and children are included in this level. The remaining large majority consists of people who are mostly self-employed or work as casual labourers, and their households. Cross-cutting this class divide, lineage communities function very well, connecting the poorer population in the villages to their salary-earning relatives in town. These communities have their natural resource base in their ancestral villages and surrounding land. (Bio)diversity in the community base allows a large extent of food sovereignty, also for the community members living in town. Relatives in the village grow rice and maize and vegetables, dry fish and collect forest products. They share part of it with their urban relatives who in turn help them out when they have to pay school fees, tax or other monetary expenses. In Sumba, a sound resource base is a prerequisite for resilience in times of crisis, because there is little insurance and only limited regular government support. Ceremonial exchange between affiliated communities during weddings and funerals keeps the community economy alive. The main currencies in that exchange are livestock (pigs, horses and water buffaloes) and hand woven ikat cloths. These ceremonial assets are also part of the community’s resource base. During the last year four factors threatened that base, thereby increasing the common people’s vulnerability.

Four disasters

The first and silently continuing change that threatens the communities’ resource base is capitalist expansion, in particular the enclosure of areas for plantations, food estates and the tourism industry. The owners and investors are companies from outside Sumba, including large national business conglomerates (like Djarum) that work locally through smaller subsidiary companies. Large plantations reduce the local population’s access to lands, in particular to the fields where they used to graze their horses, cows and goats. A former herdsman told us that he then had to keep his cattle at stable and collect fodder which is an extra claim on his labour. Selling his livestock was the only remaining option. Water problems are another impact of capitalist plantation expansion. The sugar plantation of PT MSM has appropriated the rivers and springs in the Umalulu district, using the water for irrigating sugarcane. The downstream community irrigation scheme dried up in 2016. For some local peasants who could no longer cultivate their paddy fields, the closest available alternative employment was working as casual labourer for the plantation company. Steady plantations jobs are mainly for staff from Java, while casual labourers’ wages are low and labour conditions bad. Agrochemicals in the plantation’s wastewater pollute the rivers, and will do so even more when operations are at full scale. This is a threat to community health and to fishery.

Capitalist expansion in the tourism sector decreases the local population’s access to land in similar ways as plantations do. Sumba’s coastal strip of land has been for sale for two decades. The fences that speculative land purchasers and resort owners from other areas in Indonesia have put up make access difficult. Fishermen also suffer from enclosure of coastal plots for establishing tourist resorts, because resort owners prohibit access to their territory, including their strip of beach and sea. Capitalist expansion is supported by the district government with legal permits, which turns the local population into illegal encroachers if they access their former lands or fishing areas. Although these developments are no longer news items, they have a heavy impact as basic resilience-disrupting force at work in East Sumba. Profit-oriented large-scale capitalist expansion is a disaster for the common people in Sumba, and will be eventually for the elite class and the environment as well.

The second disaster is an epidemic of livestock disease. Although peasants in Sumba are used to having pests and plant diseases in their crops, and losing some livestock to animal diseases, this epidemic was extraordinary. The African Swine Fever (ASF) entered the island Timor in 2019, and spread over the province NTT from March 2020 onwards. It killed a large part of the pig population—estimated at 2 million animals—in the province.

Pigs are extremely important in Sumba for two reasons. First, they are the main currency in ceremonial exchange, and therefore the cement of the community economy. Every important meeting or event in Sumba should end with a meal including pork. Pigs are also the most important source of savings among the village population. In our 2017 household survey, in a village with a strong resource base in the south-eastern tip of the island, we found that income from selling pigs and chicken contributed largely to household cash income that year, both for the poor (42%) and for the non-poor (72%). The ASF epidemic is like a banking crisis in which savings and assets have evaporated. The government veterinary service seems unable to prevent or stop the epidemic, which persists.

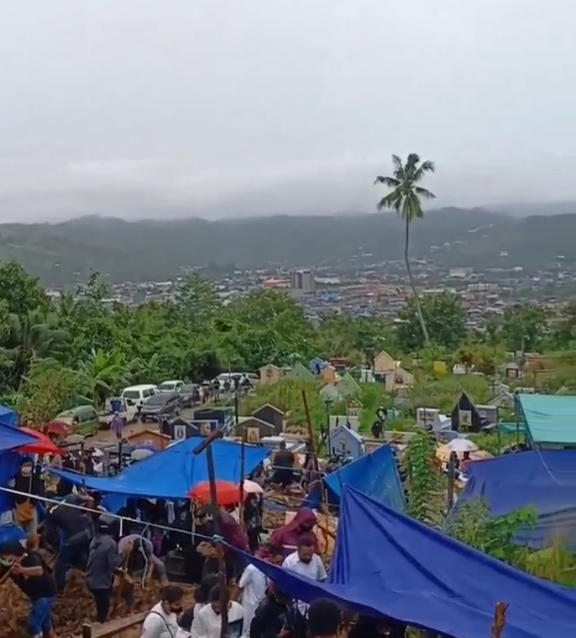

The third disaster in the past year was the cyclone that occurred on 4 and 5 April 2021. Cyclone Seroja was an extreme example of the main climate change problem of the last two decades: disturbed rainfall patterns. In daily practice this means that farmers no longer know when exactly to sow or plant their new crops; in some years there are severe droughts and in others there are floods. But this year was exceptional. Cyclone Seroja washed away crops in the lower parts of valleys and along overflowing rivers, and damaged around 5000 houses. Not far from Waingapu floods caused by the cyclone broke the Kambaniru dam, which destroyed irrigated rice cultivation in an area of 1440 hectares.

Cyclone Seroja uprooted a breadfruit tree- an important source of food security. Waingapu, 6 April 2021 © S.Makambombu

In the village mentioned above people prefer to cultivate their crops in river-bank gardens to cope with droughts. This year they lost everything. Meanwhile, the harvest in the uphill gardens was better than normal. The cyclone also toppled many trees, including rare local varieties of banana trees with famously delicious fruit. In the rice fields most crops were harvested before April, but for those who had planted late, the flood washed away everything.

Since March 2020 the COVID pandemic has become the fourth disaster. In last year’s article we wrote how the mitigating measures had negative effects on the local economy. By mid-June 2020, trade opportunities were slightly restored after the provincial government eased lock down measures. Communities could gather again for ceremonial events, be it with limited attendance. There were no tourists to buy food, snacks or handwoven cloths from locals. The single high-end resort on the island was the exception, where the world’s rich continued to enjoy perfectly comfortable self-isolation. For a long time the number of infections remained low, and particularly in rural areas there was little sign of a pandemic.

At the end of June 2021 that changed. The number of positive cases went up from 92 on 28 May to 860 on 21 July. That is extremely worrying, because the island lacks sufficient, capable health care facilities. By 26 July 2021, government health service data indicated 3,215 infections in East Sumba the outbreak of the pandemic, with 62 deaths. On that day, 935 people were being treated: 34 patients in Waingapu’s public hospital (which is its full capacity) and 31 in the official public quarantine facility. The remaining 879 were in self-isolation at home, where they should receive medical supervision from the local health post. However, that does not always happen, particularly outside of the capital. Government Health Service data about the spread of the infections in East Sumba indicated proliferation to nearly all subdistricts by 21 July .

Case numbers on 21 July, according to the East Sumba Regency Coordinating Post for the Accelerated Prevention and Treatment of COVID-19.

Most instances occur in the capital town and adjacent area, and are concentrated around the sugar plantation, PT MSM. However, the figures only represent positive test results in an area with low testing capacity. We do not know how many people have been infected in reality. Many “self-employed” people in East Sumba prefer not to get tested, either embarrassed by the stigma of “COVID-positive”, or unable to risk the loss of income due to a 14-day mandatory self-quarantine.

The vaccination rate in East Sumba is below the national level in Indonesia. By 12 July 2021, of a total population of 26,500 in 2020, 10 percent had received at least one vaccination (13.4 percent nationally), while 2.5 % is fully vaccinated (5.6 % nationally). Civil servants were prioritised for vaccination; they make up 58% of the total vaccinated population in this area. Common people’s vulnerability to COVID infections is very high.

Related

Infection rates appear low in NTT, but the economic impacts of the pandemic combined with poor harvest yield are potentially devastating.

Resilience during the mix of disasters

Zooming in to our field research in three villages, we glimpse how the mix of disaster factors has affected people in varying ways.

First of all, in the two most remote villages there were no cases of COVID infection reported up to July 2021. By contrast, the sugar plantation, close to the third village, became a centre of infections after staff members from Java had spent their Ramadan holidays in their hometowns, with 113 cases on 21 July 2021. The adjacent village had 10 positive cases at that time. This suggests that plantation labourers are more vulnerable to getting infected than the peasants in the remote villages.

A positive development in the three villages, and all over East Sumba, was that the rainy season was abundant and early. Even in the usually driest areas people began cultivating rice and maize in November and harvest in February and March 2021. The heavy rains during Cyclone Seroja did not only lead to disaster. The area with the village irrigation scheme downstream from the sugar plantation benefitted from water excess. In the middle of the rice fields springs appeared and upstream, rivers that would usually be dry by April were flowing. Many people could grow a second rice crop, even on high plots. Consequently, 2021 has seen an excellent rice harvest in East Sumba. For peasants who grow maize and other dry land crops the year was not as good. Too much rain stimulated pests in these crops.

The rough seas with storms and rain brought a huge amount of seas grass to the coast of East Sumba, offering sea grass gatherers a great income.

The mix of disasters led to a steady flow of emergency assistance from the government. Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, villagers have received direct cash support in the two remotest villages. A villager told us that all households had received a small grant from the Village Fund (Dana Desa), because in this COVID year the village government had cancelled all plans for building roads or bridges, simultaneously cutting off income opportunities for village road workers. Regular forms of government social support also continued. After the cyclone there was emergency aid for those whose houses had been severely damaged.

There was also a positive effect for ex-migrant workers. Because the heavy rains extended the wet season there was more time and opportunity to grow crops. That was fortunate for those who had returned to the village after losing their jobs as migrant workers in other parts in Indonesia. Cultivating community lands offered work, food and income, and new ideas for improving farming produce and techniques.

When the severe lock down measures were lifted in June 2020, villagers continued the ceremonial events they had postponed for months. However, they lacked the livestock they needed for ceremonial exchange, because of the swine fever epidemic and reduced access to grazing lands, where previously they would let their horses and cattle graze freely. As a solution, societal consensus allowed a change of norms: gifts of pigs, horses and buffaloes could be replaced by cash contributions, whereas beef (instead of pork) became accepted for the meals at these events. A second saving solution was that traditional leaders decided to reduce the duration of ceremonial events as well as the number of invitations. The change is temporary, leaders say, but this adaptation might last if the causes of crises continue.

Continuing vulnerability

Although there have been positive results from the mix of disasters in East Sumba, demonstrating remarkable resilience, we should not conclude that the problems have been solved. What is described above is not a series of incidental disasters, but the result of structural problems related to capitalist expansion, climate change and recurring global epidemics.

If next season will be one of drought again in East Sumba, people will suffer from the sugar plantation’s water grabbing. So long as there is no vaccine for African Swine Fever there will be a continuing ‘banking crisis’ in Sumba. If common people in Sumba do not get COVID-19 vaccinations soon many people’s lives will be at risk.

In absence of a welfare state that reaches all citizens, the district and village governments of East Sumba should give top priority to (legally and environmentally) protecting communities’ resource bases, instead of supporting capitalist expansion which depletes the island’s resources and exports profits out of reach of the local population.

The post Surviving Four Disasters in Sumba appeared first on New Mandala.

This post was originally published on New Mandala.