Janine Jackson interviewed Groundwork Collaborative’s Rakeen Mabud about greedflation for the February 9, 2024, episode of CounterSpin. This is a lightly edited transcript.

CounterSpin240209Mabud.mp3

Janine Jackson: If you buy groceries, you know that prices are high. And if you read the paper, you’ve probably heard that prices are high because of, well, “inflation,” and “shocks to the supply chain,” and other language you understand, but don’t quite understand.

One article told me that

economists see pandemic-related spending meant to stabilize the economy as a factor, along with war-impacted supply chains and steps taken by the Federal Reserve to raise interest rates

—all of which may be true, but still doesn’t really help me see why four sticks of butter now cost $8.

Not to mention that the same piece talks matter of factly about “upward pressure on wages,” which sounds like people who need to buy butter are getting paid more, but I’m pretty sure the language is telling me I’m supposed to be against it.

How do we interpret corporate news media’s coverage of prices? What aren’t they talking about?

Rakeen Mabud is chief economist and managing director of policy and research at Groundwork Collaborative. She joins us now by phone. Welcome back to CounterSpin, Rakeen Mabud.

Rakeen Mabud: Thank you so much for having me. It’s great to be back.

JJ: I want to say, the piece that I’m citing in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette isn’t a bad piece. It’s just what passes for media explanation of what is a truly meaningful reality. People are really having trouble buying diapers, and buying food. And so to have journalists saying, “Well, it’s because of the blahdy blahdy blahdy blah that you couldn’t possibly understand”—the unclarity of it is galling to me, and it’s politically stultifying. I’m supposed to get mad at inflation, per se?

That’s the kind of informational void that Groundwork Collaborative’s work is intervening in. So let me just ask you to talk about what you find when you look into, for example, high grocery store prices right now.

RM: Yeah, this is a great question, and I love the fact that you’re focusing on the experiences of people, because that’s how we all experience the economy and, frankly, that’s how the economy is made, right, through our actions, through our demand, through our spending. And so it is really important to hone in on what’s going on to people on the ground, as we’re thinking about these big, amorphous concepts like inflation.

And the reality is, as you point out, prices are sky high for people around the country, and folks are really struggling. Grocery prices, obviously, are particularly worth digging into, because there’s a real salience of food prices in everybody’s lives. We all go to the grocery store on a weekly or maybe biweekly basis, and buy groceries to feed ourselves, and feed our families.

And my colleagues at the Groundwork Collaborative, Liz Pancotti, Bharat Ramamurti and Clara Wilson, recently authored a report that really digs into what’s going on with grocery prices. And what they find is that grocery price increases have outpaced overall inflation, and families are now paying 25% more for groceries than they were prior to this pandemic, compared to 19% of overall inflation. So there’s this gap between what folks are paying at the till, and what inflation would suggest.

And this is particularly hitting folks who are on the lower income end of the income distribution harder. In 2022, people in the bottom quintile of the income spectrum spent 25% of their income on groceries, while those in the highest quintile spent just under 3.5%.

And this is a trend that we see across the board with essentials. Because if something is essential, you have to buy it. If you earn less money, a bigger proportion of your income is going to go towards those essentials. And so that means that when you see inflation and, frankly, corporate profiteering, which I’ll get into in a second, showing up in spaces for essential goods, it’s always the people who are most vulnerable who are hit the hardest.

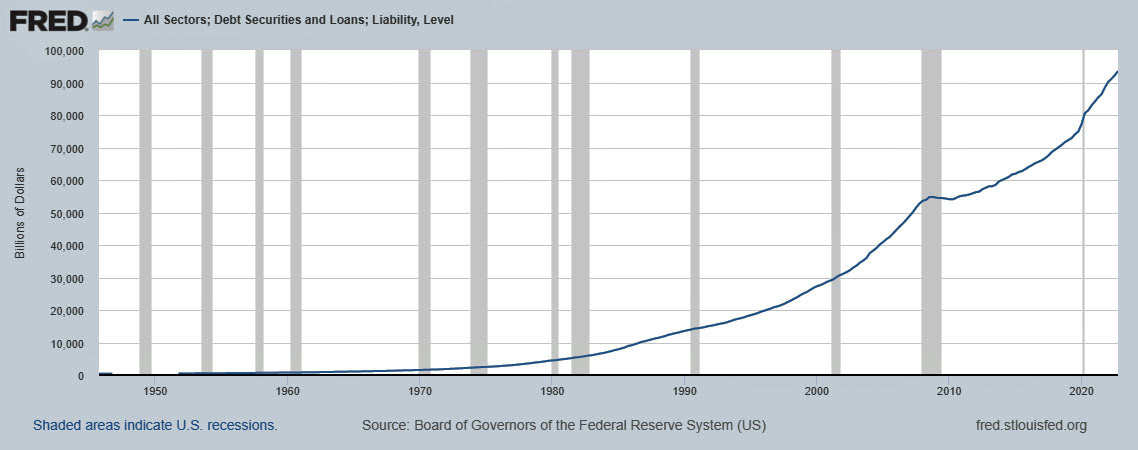

It’s wonderful that you’re really focusing in on groceries. And I think one thing to note, just to zoom out a little bit from grocery prices in particular, is that an underexplored topic still, I think, in the discussions around inflation is the role of corporate profit margins. Because the fact remains that corporate profit margins have remained high and even grown, even as labor costs have stabilized, input costs—the costs of things that are used to produce goods—have come down, and supply chain snarls have started to ease.

And in a different paper by two other of my colleagues, Lindsay Owens and Liz Pancotti, they find that from April to September of 2023, so that’s very recently, corporate profits drove 53% of inflation. When you compare that to the 40 years prior to the pandemic, profits drove just 11% of price growth.

There are a lot of explanations out there of what’s causing inflation, but it’s very important to focus on the role of big companies using the cover of inflation to jack up prices. And they continue to do that, even as their own costs are coming down.

JJ: And I want to say, you can illustrate that point with just data, as these works from Groundwork Collaborative do, but at the same time, you also have, as the kids say, receipts—in other words, earnings calls where CEOs are saying it out loud: Their situation in terms of supply chain, in terms of Covid and whatever, they’re using that as an opportunity to keep prices high.

RM: Yes, absolutely. So let’s talk about another essential good, which is diapers. And I think diapers are really a good example, because it illustrates what’s going on right now, and ties together the idea of corporate profiteering, but also this idea that, as scholars Isabella Weber and Evan Wasner put out there, about tacit collusion and implicit collusion. So let’s unpack that. What does that all mean?

So what they write about is that inflationary environments, when prices are rising across the board, it means that companies, especially those that are in a really concentrated market, can raise their prices, precisely because they know that their competitor is going to do the exact same thing. So if you are one of three big companies, and you know that your competitors are also going to raise prices, there’s no reason for you not to raise prices.

And that logic also applies in the reverse. So when costs are coming down, if you know that your competitors are going to keep their prices high, you’re also going to keep your prices high, which is I think why we’re seeing, even as input costs come down, prices are staying high, and people are still paying more than they should be, given the cost of input.

So diapers, right? Diapers, I think, is the perfect example for this. It’s a super, super concentrated market. Proctor & Gamble and Kimberly-Clark control about 70% of the domestic market, and diaper prices have increased by more than 30% since 2019, from about $16–$17 to nearly $22.

The main thing that goes into producing diapers is wood pulp. It’s also the main input into toilet paper, paper towels, basically paper products that we use around the house. The wholesale wood pulp prices really skyrocketed, by 87% between January 2021 and January 2023.

But in 2023, between January and December of 2023, [wood pulp] prices declined by 25%, but diaper prices have remained high. So what’s going on here?

And to your point, the executives at Kimberly-Clark and Procter & Gamble are not hiding the ball. P&G CFO said on their October 2023 earnings call that high prices were a big driver of the reason that they could expand their profit margins, and that 33% of their profits in the previous quarter were driven by lower input costs. And during their July 2023 earnings call, the company predicted $800 million in windfall profits because of declining input costs.

Same thing on the other side, on Kimberly-Clark’s side; their CEO said in October that the company “finally saw inflection in the cost environment.” And he admitted that he believes the company has a lot of opportunity to “expand margins over time,” despite what they’re “doing on the revenue side and also on the cost side.” So despite large input cost decline, the CEO thinks that the company has priced appropriately, and didn’t anticipate a new price deflation.

So diapers, I think, is a really clear example of how these big corporations are exercising their corporate power in a moment where things are a little murky for consumers. We don’t know, necessarily; we don’t have all the data at our fingertips, or the time, frankly, to figure out: Is the box of diapers more expensive for sensible reasons or not? And these big companies are taking advantage of both the information asymmetry, and the particular inflationary environment we’re living in.

JJ: And you don’t have a choice. You’ve got to buy the diapers. You can try to puzzle out why it costs more than it cost a year ago, or six months ago, but you still have to buy them. And that’s the thing.

I want to draw you out on something, because I see articles—it’s not that media are not ever saying “greedflation,” or that they’re completely ignoring the idea that corporations might be keeping prices high to profit, although it’s still not shaping the dialogue in the way that you would hope. But I do see articles that put “corporate profiteering” in scare quotes, as if it’s not a real thing; it’s just an accusation. And I wonder, what do we call “profiteering,” and how does it differ from capitalism doing its capitalism thing?

Rakeen Mabud: “The truth of the matter is there are vested interests for folks to want to vilify workers, to want to vilify big public investments.”

RM: This is a question that I’ve gotten over the years, as we’ve done this work. It is not necessarily a bad thing for companies to be making a profit. That’s OK. Companies exist to make a profit. What we’re talking about here is really profits above and beyond what they should be making: excess profits, windfall profits, and companies making these profits on the backs of consumers.

The example that I always go back to is just the classic price-gouging example. If you are in the middle of a hurricane or a disaster relief situation, and you are a person who sells bottles of water, or gallon jugs of water—if you jack the prices up because you know that people are going to need that water, because there’s no safe tap water to drink, that’s price-gouging, and that is illegal.

And yet that happens across our economy all the time. And we’ve seen that in particular over the last couple of years, as we’ve experienced the pandemic and have gone through these series of crises. And yet we don’t point it out.

And I think part of the reason this idea is not taken seriously, again, there’s a couple of reasons. The first is that it doesn’t accord with the traditional story of where inflation comes from. The traditional story of where inflation comes from is, workers are super greedy, they’re asking for higher wages. And so we end up with higher wages, which push up prices, which force people to ask for higher wages. And you end up with what economists call a wage-price spiral.

The other factor in the traditional story about where inflation comes from is, too much public investment flooding the economy is just going to jack up prices.

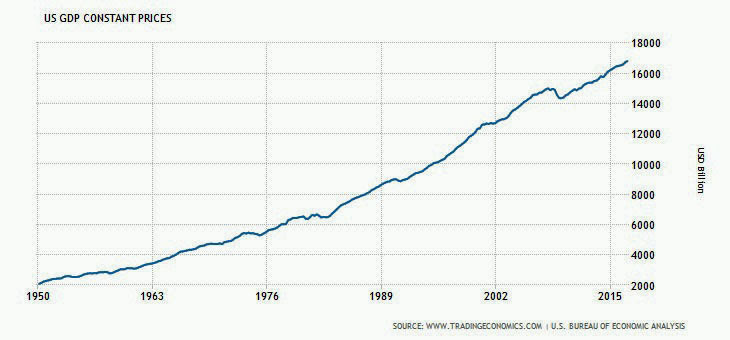

And the reality of the situation is that wasn’t the case here. We have seen historic public investment, and inflation’s come down. We have seen a strong labor market. We haven’t had to put millions of people out of work in order to bring prices down.

And so the textbook story of how inflation works is not really holding water in the moment. It’s not according with literally the reality that we’re seeing in the data.

And the truth of the matter is there are vested interests for folks to want to vilify workers, to want to vilify big public investments, and to continue to perpetuate an environment where big corporations can hold power and hold money and earn windfall profits on the backs of consumers. So I think it’s really important to know that this is a narrative that’s new, and it’s a narrative that is challenging for the dominant stories about how inflation works.

But the reason it has made a toehold, and I think more than a toehold at this point—I mean, even the Wall Street Journal in December had a headline that said, “Outsize Profits Help Drive Inflation. Now Consumers Are Pushing Back.” The reason it’s gotten its feet on the ground is because of the experience of people across the economy, this is exactly how people are experiencing the economy, and it’s the truth of the matter.

And I think that is really what certainly my work is always trying to do, is let’s get to how people are experiencing the economy and speak to their concerns, because people know what’s up. You don’t need to tell them that big companies are exploiting them. They are very willing to believe it, because it’s how they’ve interacted with the economy for years.

JJ: I have to say, the idea that there’s an abstraction that I’m supposed to pay obeisance to, and it’s going to keep wages down and public investment down, but somehow I’m still supposed to be for it, is kind of strange to me, the idea that I’m supposed to be so opposed to inflation that I’m supposed to be against higher wages for workers, and I’m supposed to be against more public investment. It just shows how far we’ve gone in fealty to an abstraction, essentially, in terms of economic understanding. I find it very odd to have folks saying, “Oh, I don’t want upward pressure on wages, because somehow that’s going to be bad for me ultimately down the road.” It seems to me a kind of distortion of our understanding of the way an economy should work, and who it should serve.

RM: Right, I mean, we are the economy. That’s what we’re always saying at Groundwork, that we are the people, the regular people are the people who are the economy, and it’s our wellbeing that reflects whether the economy is doing well.

And I also think it’s important in conversations about inflation, I think; we pay attention to prices and cost of living and affordability in a moment of crisis. But the truth of the matter is that the high prices that people have been feeling in their household budget long predate this particular inflationary moment: the cost of childcare, the cost of healthcare, the cost of housing, the cost of education. All of these things go beyond what we’re experiencing in this particular moment. They have been burdens on people for decades.

And there are also structural factors that are perpetuating these burdens. So I think housing costs are a really good example. Housing costs are up about 21%, and we have this longstanding shortage of affordable and high-quality housing in this country. There have been instances, over the course of the last couple of years, where we’ve seen big home builders and landlords celebrating inflation as a way to restrict housing supply. Literally had a home builder say, “We could build a thousand more houses, but we’re not going to, because it’s going to help us restrict supply, and therefore jack up the prices of the homes we can build.” We’ve also seen landlords really celebrating inflation as a way to skim a little bit more off the top by raising rent a little bit higher.

So all of that is certainly happening, but we also need to pay attention to broader macroeconomic forces in perpetuating this housing crisis. So one of the best ways, kind of a no-brainer, of addressing a housing supply shortage is to build more houses. But the Federal Reserve, since we last spoke, has embarked on an interest rate–hiking rampage. What does that do? Sky-high interest rates crush new housing construction, because it stymies private investment, and it pushes potential buyers, because of high mortgage rates, back into the rental market, which pushes rents up.

So the Federal Reserve says, “We’re raising interest rates through this theory and this channel that we think works,” which, by the way doesn’t, because again, as I mentioned, we haven’t necessarily seen mass unemployment in order to bring down prices. But they’re saying, we’re trying to bring down prices, guys; we’re trying to bring down prices by raising interest rates. But really what they’re doing is making the problem worse, and they’re perpetuating this cost-of-living crisis that long predates the pandemic.

And so it’s really important, I think, to also call out big institutional actors, like Chair Powell, to lower rates immediately, given that it’s clear from the data that his rate hikes hadn’t had the intended effect, and are actually making the problem worse.

Groundwork Collaborative (2/24)

JJ: One of the latest reports from Groundwork is called “What’s Driving the Rise in Grocery Prices–and What the Government Can Do About It.” So let me ask you, finally, and it’s a lot, but what can government do about the problems that we’re talking about?

RM: I think, actually, we’re living in an exciting time when it comes to an expansiveness in the policy tools that folks are thinking about and using in order to bring down prices. We’re not in your 1970s inflationary world, where we’re just hoping that the Federal Reserve does its job and hoping for the best. They’ve sort of been discredited, and, again, time to bring down interest rates.

But we’ve seen President Biden and his administration really taking the issue of profiteering seriously. I mean, just last month, he said to any corporation that has not brought their prices back down, even as inflation has come down, even as supply chains have been rebuilt, it’s time to stop the price-gouging. To have that come from the president, to call out the big corporate actors who are taking advantage of people and lining their coffers, is remarkable.

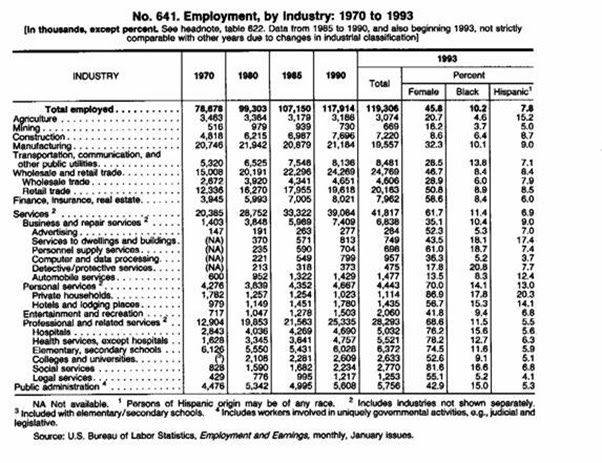

And I think it’s not just words, right? The administration has taken some really early actions promoting competition in really concentrated markets—like meat packing, a sector that is really driving grocery-price inflation right now.

Agencies like the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau are going hard after junk fees. Those are the sort of, when you check into a hotel, it says resort fee, this fee, that fee, and you never really know what you’re paying for. And the truth is, you’re just paying for these companies to get richer, right? So that in banking, overdraft fees, the CFPB has been going hard after junk fees.

The FTC and the DoJ are aggressively using their authority to crack down on the concentration that allows these companies to get away with jacking prices up on consumers.

And so I think what we need to see is a continuation of that. Look at anti-competitive mergers, especially throughout the food industry, but other industries where they’re producing essentials, to make sure that these environments that facilitate and breed both profiteering and tacit collusion are not allowed to be created. Finalize regulations that improve fairness, competition and resiliency in supply chains.

And then the last policy idea here was—it feels a little bit unrelated, but it’s actually one and the same—we have a big opportunity to tackle the full problem of high prices coming up, because many of the provisions of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, the 2017 Trump tax cuts, are expiring at the end of 2025. And one of the best ways to tax excess profits is simply to raise the corporate tax rate. That’s it. It’s a pretty easy policy, and one that people understand and can get behind.

JJ: Thank you very much. We’ve been speaking with Rakeen Mabud, chief economist and managing director of policy and research at Groundwork Collaborative, online at GroundworkCollaborative.org. Thank you so much, Rakeen Mabud, for speaking with us this week on CounterSpin.

RM: Thank you so much for having me. It was such a pleasure.

The post ‘It’s Important to Focus on Big Companies Using the Cover of Inflation to Jack Up Prices’ appeared first on FAIR.

This post was originally published on FAIR.