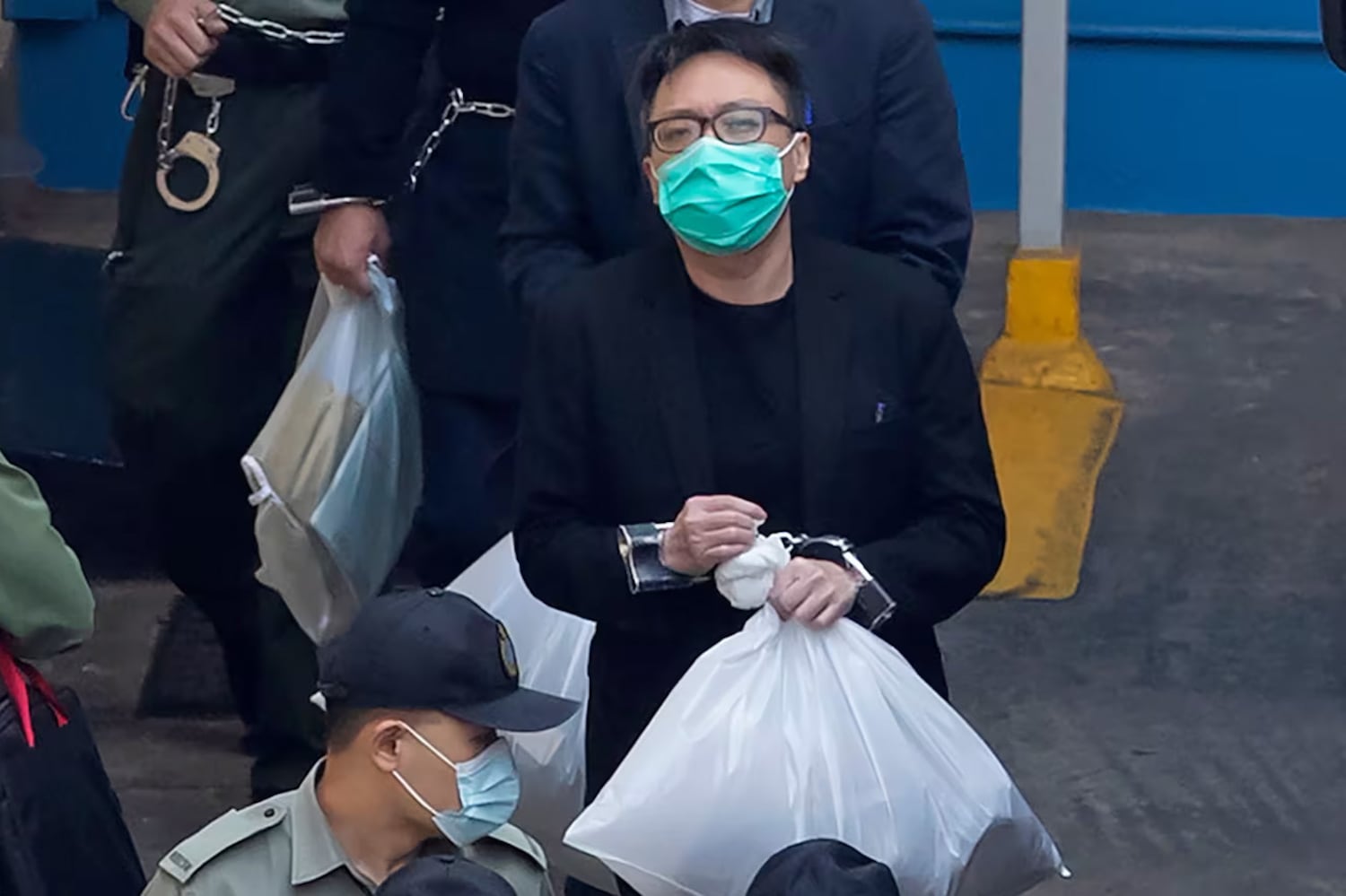

Hong Kong’s Cardinal Joseph Zen, previously arrested under the Beijing-imposed national security law, was allowed to leave the city to attend Pope Francis’ funeral in an apparent show of leniency for the retired bishop known for being a vocal critic of China’s interference in church affairs.

Zen, 93, departed for Vatican City on Wednesday evening after a court granted the temporary return of his passport, which was confiscated after his arrest in 2022 for allegedly colluding with foreign forces and endangering national security, two sources told Radio Free Asia.

Cardinal Zen, who is currently on bail after his 2022 arrest, is traveling with a member of the Salesian religious congregation, one of the largest groups in the church, the sources said. They spoke on the condition of anonymity for fear of reprisals.

World leaders, including U.S. President Donald Trump, U.K. Prime Minister Keir Starmer, French President Emmanuel Macron, and Italian Prime Minister Giogia Meloni, are expected to attend the funeral of Pope Francis, who died Monday at the age of 88.

The papal funeral is scheduled to take place on Saturday.

Cardinal Stephen Chow, the current bishop of Hong Kong, has also arrived in Rome to attend Pope Francis’s funeral and participate in the secret conclave to vote for the new pope, according to the city’s Catholic Social Communications Office.

In Italy, Zen will be received by Father John Paul Cheung, a priest from the Salesian order, who will help coordinate his schedule there, the sources said.

The Associated Press on Thursday quoted Cardinal Zen’s secretary as confirming that the retired bishop had recently applied to the court for his passport to be released.

The cardinal intends to return to Hong Kong after attending the funeral, though the exact date of his return is yet to be confirmed, the AP reported, citing his secretary.

Earlier in the week, Zen criticized the Vatican for providing only a day’s notice before convening the first General Congregation, prior to the papal conclave, saying the short notice made it difficult for elderly cardinals from peripheral regions to arrive on time.

Conditions for travel

This is not the first time Cardinal Zen has been permitted to retrieve his passport. In January 2023, he was allowed to attend the funeral of Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI.

During that visit, Zen met privately with Pope Francis — their first meeting since Zen’s 2022 arrest. In a later interview, Francis had described Zen as “a gentle soul,” while Zen, in turn, said Pope Francis made him feel very warm and comforted.

The conditions for Zen’s travel are expected to be similar to those in the past, including a ban on media interviews and surrender of his passport to the police upon his return, in accordance with bail conditions for those arrested under the national security law.

In May 2022, Zen’s arrest by Hong Kong’s national security police along with other pro-democracy figures sparked international outrage from governments and rights activists.

Later that year, he and his co-defendants were fined after being found guilty of failing to properly register their 612 Humanitarian Relief Fund, which offered financial, legal and psychological help to people arrested during the city’s 2019 protest movement.

They are scheduled to appear in court for an appeal hearing on Dec. 3, 2025.

Zen has been critical of the Vatican’s controversial agreement with China to allow the Chinese government to propose candidates for bishop.

In particular, he has accused Cardinal Pietro Parolin – the Vatican’s secretary of state and a frontrunner to become the new pontiff – of being “a man of little faith,” for his role in architecting the deal that many say undermines the church’s mission in China.

The next pope will be elected by the College of Cardinals in a secret conclave. Zen, like other cardinals aged over 80, does not have voting rights but can participate in the discussions.

Of the three cardinals in the Hong Kong diocese, only Chow, 65, is eligible to vote. Ascending to the papacy requires the votes of 90 out of 135 cardinals eligible to participate in the Vatican conclave.

Several prominent cardinals who oversee dioceses in Asia are regarded by the region’s faithful as worthy candidates to lead the world’s 1.4 billion Catholics. An Asian pope would be a first for the church.

Edited by Tenzin Pema and Mat Pennington.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by RFA Cantonese.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.