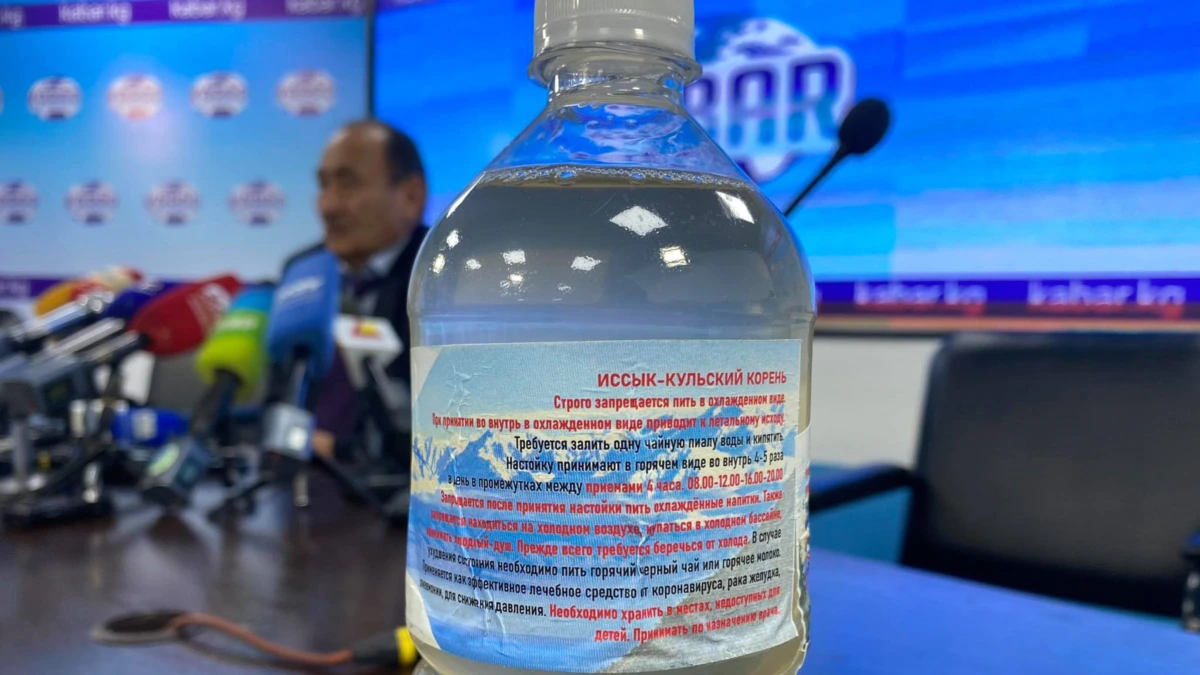

Amnesty International says some measures to tackle the coronavirus pandemic have aggravated existing patterns of abuses and inequalities in Europe and Central Asia, where a number of governments used the crisis “as a smokescreen for power grabs, clampdowns on freedoms, and a pretext to ignore human rights obligations.”

Government responses to COVID-19 “exposed the human cost of social exclusion, inequality, and state overreach,” the London-based watchdog said in its annual report released on April 7.

According to the report, The State of the World’s Human Rights, close to half of all countries in the region have imposed states of emergency related to COVID-19, with governments restricting rights such as freedom of movement, expression, and peaceful assembly.

The enforcement of lockdowns and other public health measures “disproportionately” hit marginalized individuals and groups who were targeted with violence, identity checks, quarantines, and fines.

Roma and people on the move, including refugees and asylum seekers, were placed under discriminatory “forced quarantines” in Bulgaria, Cyprus, France, Greece, Hungary, Russia, Serbia, and Slovakia.

Law enforcement officials unlawfully used force along with other violations in Belgium, France, Georgia, Greece, Italy, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Poland, Romania, and Spain.

In Azerbaijan, arrests on politically motivated charges intensified “under the pretext” of containing the pandemic.

In countries where freedoms were already severely circumscribed, last year saw further restrictions.

Russian authorities “moved beyond organizations, stigmatizing individuals also as ‘foreign agents’ and clamped down further on single person pickets.”

Meanwhile, authorities in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan adopted or proposed new restrictive laws on assembly.

Belarusian police responded to mass protests triggered by allegations of election fraud with “massive and unprecedented violence, torture and other ill-treatment.”

“Independent voices were brutally suppressed as arbitrary arrests, politically motivated prosecutions and other reprisals escalated against opposition candidates and their supporters, political and civil society activists and independent media,” the report said.

Across the region, governments in Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Bosnia-Herzegovina, France, Hungary, Kazakhstan, Poland, Romania, Russia, Serbia, Tajikistan, Turkey, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan “misused existing and new legislation to curtail freedom of expression.”

Governments also took insufficient measures to protect journalists and whistle-blowers, including health workers, and sometimes targeted those who criticized government responses to the pandemic. This was the case in Albania, Armenia, Belarus, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Hungary, Kazakhstan, Kosovo, Poland, Russia, Serbia, Turkey, Ukraine, and Uzbekistan.

In Tajikistan and Turkmenistan, medical workers “did not dare speak out against already egregious freedom of expression restrictions.”

Erosion Of Judicial Independence

Amnesty International said that governments in Poland, Hungary, Turkey, and elsewhere continued to take steps in 2020 that eroded the independence of the judiciary. This included disciplining judges or interfering with their appointment for demonstrating independence, criticizing the authorities, or passing judgments that went against the wishes of the government.

In Russia and in “much” of Eastern Europe and Central Asia, violations of the right to a fair trial remained “widespread” and the authorities cited the pandemic to deny detainees meetings with lawyers and prohibit public observation of trials.

In Belarus, “all semblance of adherence to the right to a fair trial and accountability was eroded.”

“Not only were killings and torture of peaceful protesters not investigated, but authorities made every effort to halt or obstruct attempts by victims of violations to file complaints against perpetrators,” the report said.

Human Rights In Conflict Zones

According to Amnesty International, conflicts in countries that made up the former Soviet Union continued to “hold back” human development and regional cooperation.

In Georgia, Russia and the breakaway regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia continued to restrict freedom of movement with the rest of the county, including through the further installation of physical barriers.

The de facto authorities in Moldova’s breakaway Transdniester region introduced restrictions on travel from government-controlled territory, which affected medical provisions to the local population.

And in eastern Ukraine, both Ukrainian government forces and Russia-backed separatists also imposed restrictions on travel across the contact line, with scores of people suffering lack of access to health care, pensions, and workplaces.

Last fall’s armed conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan resulted in more than 5,000 deaths and saw all sides using cluster munitions banned under international humanitarian law, as well as heavy explosive weapons with wide-area effects in densely populated civilian areas.

Both Azerbaijani and Armenian forces also “committed war crimes including extrajudicial execution, torture of captives and desecration of corpses of opposing forces.”

Shrinking of Human Rights Defenders’ Space

Amnesty International’s report said some governments in Europe and Central Asia further limited the space for human rights defenders and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) through “restrictive laws and policies, and stigmatizing rhetoric.”

This “thinned the ranks of civil society through financial attrition, as funding streams from individuals, foundations, businesses and governments dried up as a consequence of COVID-19-related economic hardship.”

The Kazakh and Russian governments continued moves to silence NGOs through smear campaigns.

Authorities in Kazakhstan threatened over a dozen human rights NGOs with suspension based on alleged reporting violations around foreign income.

Peaceful protesters, human rights defenders, and civic and political activists in Russia faced arrests and prosecution.

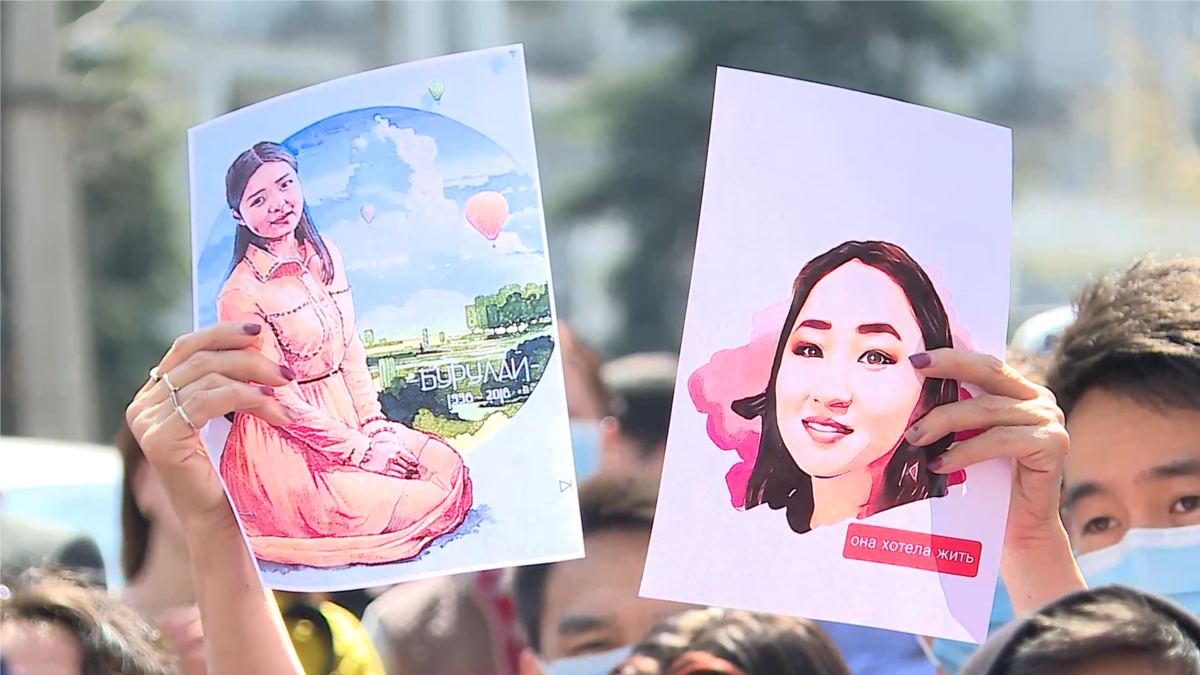

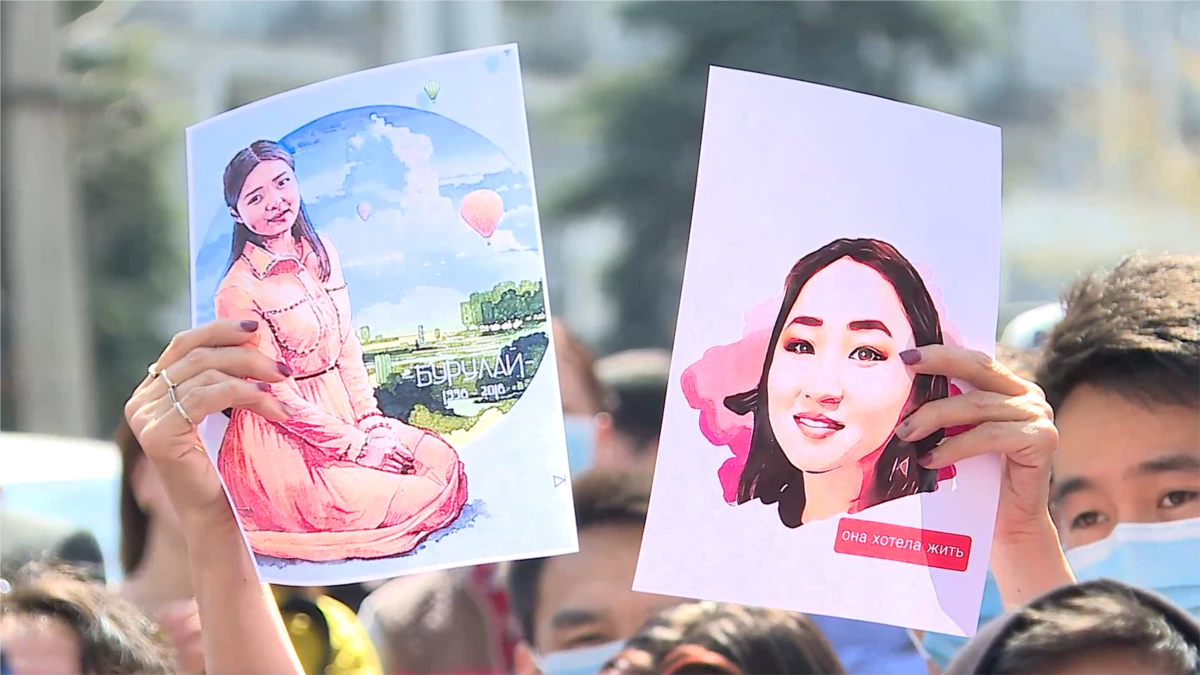

In Kyrgyzstan, proposed amendments to NGO legislation created “onerous” financial reporting requirements, while “restrictive new NGO legislation was mooted” in Bulgaria, Greece, Poland, and Serbia.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.