The clock is ticking on the Colorado River. The seven states that use its water are nearing a 2026 deadline to come up with new rules for sharing its shrinking supplies. After more than a year of deadlock, there are rumblings of a new plan, but it’s far from final.

So what happens if the states can’t agree before that deadline?

There’s no roadmap for exactly what would happen next, but policy experts and former officials can give us some ideas. It would likely be complicated, messy and involve big lawsuits.

“I think people are looking for a concise answer here,” said Brenda Burman, former commissioner of the Bureau of Reclamation. “But there isn’t a concise answer.”

While the details of that hypothetical future are fuzzy, experts generally agree on one thing: the states should do everything they can to avoid missing that deadline and heading into uncharted territory.

“It’s our job to make sure that we are setting the path for the next 20 or 30 years of stability,” said Burman, who now manages the Central Arizona Project. “And if we fail in that job, shame on us.”

Former federal officials can give some of the best insight into what might happen without a state deal, because federal agencies would likely step in to make sure reservoirs and dams stay functional. The Bureau of Reclamation, which manages water infrastructure across the West, and its parent agency, the Department of the Interior, would become major power players.

Falling back to a ‘nightmare scenario’

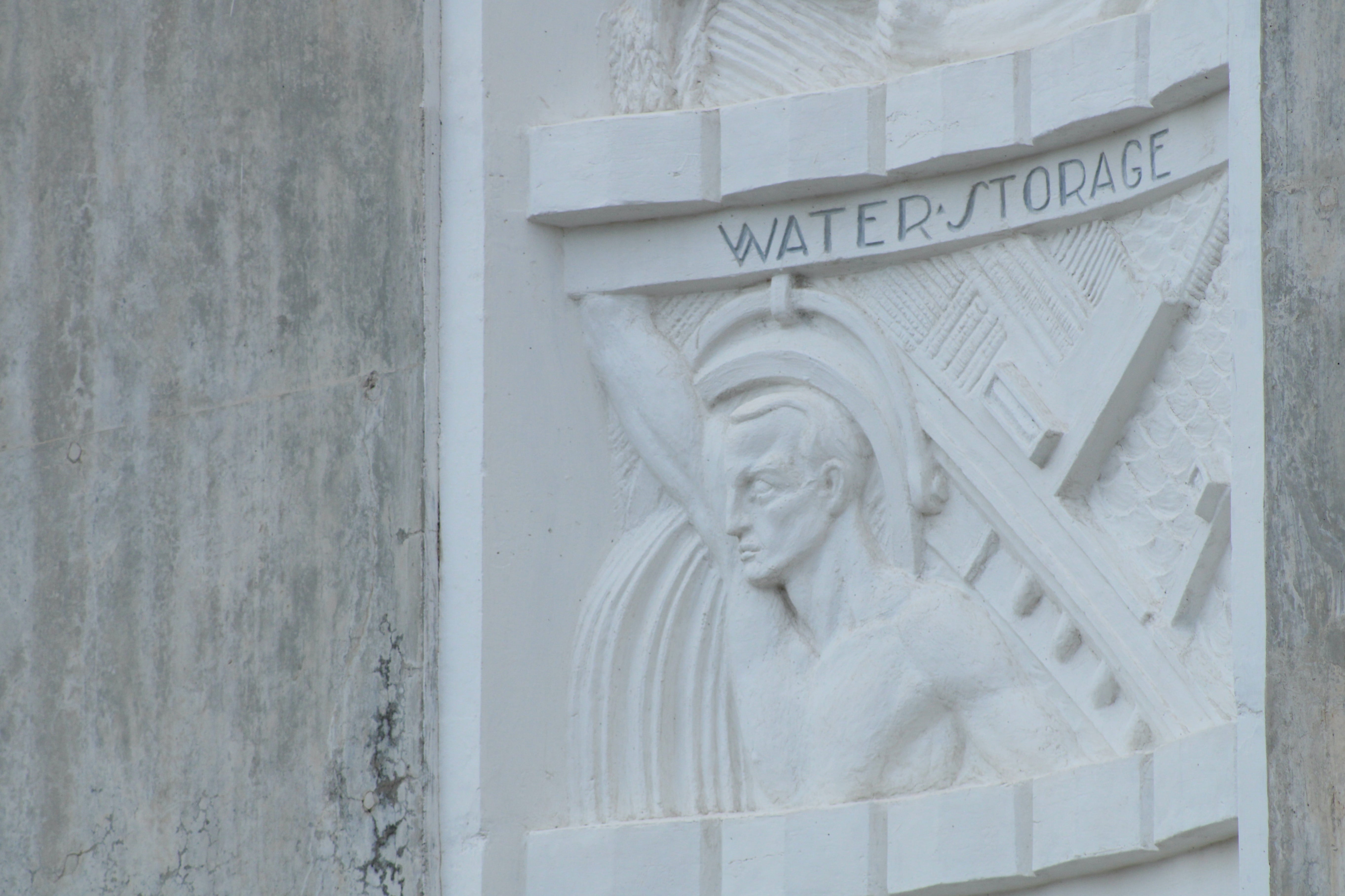

For more than a century, the Colorado River has been governed by a legal agreement called the Colorado River Compact. It was signed in 1922, when the river — and the West — looked a lot different. Over the years, policymakers have added a patchwork of temporary rules to adapt to modern times.

In this century, climate change has driven the need to adapt. The river has been in a megadrought that goes back to 2000. With less water in the river, states have had to cut back on demand, even though the compact promises more water to users than the river itself could ever provide naturally. Drought conditions have become the new normal over the past two decades, and temporary rules that were implemented to rein in water demand aren’t keeping up with the pace of drying.

The current rules for managing water were first implemented in 2007. They were slightly modified in 2012 and then expanded in 2019. All of those rules are set to expire in 2026. That expiration is the reason states are in a pinch to draw up new rules right now.

The absolute last-chance deadline to implement new guidelines is October 1, 2026. If the states fail to submit a plan for managing water by then, the Colorado River would fall back to management rules from the 1970s.

Experts say those rules, known as the Long Range Operating Criteria, or LROC, are “woefully insufficient” to deal with today’s drier, smaller river.

“That’s a nightmare scenario,” said Anne Castle. “And I don’t think that the states or the federal government would allow that to happen.”

Castle, a longtime water lawyer who served as assistant secretary for water and science at the Interior Department, said releasing water in accordance with those 1970s rules would quickly drain the nation’s largest reservoirs, Lake Mead and Lake Powell. That would jeopardize hydropower generation at major dams and could make it impossible to pass water from one side of those dams to the people and businesses downstream.

Interior, which would presumably prefer to avoid failure at the dams it runs — Hoover Dam and Glen Canyon Dam — would likely get involved to stop reservoirs from losing their water. In the absence of guidance from the states, the Secretary of Interior could use his authority as the river’s “water master,” a role that gives him some legal power to make decisions about who gets how much water.

And this administration has already made it clear that the current chief — Doug Burgum — would take advantage of that position. Scott Cameron, one of the highest ranking Colorado River officials in the Trump Administration, said as much to a conference of water experts gathered in Colorado in early June.

“Secretary Burgum is prepared to exercise his responsibility as water master,” Cameron said. “He’s not looking forward to that, but in the absence of a seven state agreement, he will do it.”

Federal action and likely lawsuits

Say the Interior Secretary becomes water master and has to pull some levers on the Colorado River. The next big question is, which levers would he pull?

His first option is the path of least resistance — sticking with those 1970s rules. They would send a lot of water from the top half of the river to the bottom. So the Upper Basin states of Colorado, Utah, Wyoming and New Mexico might want to take Interior to court.

“No one could possibly come up with a set of rules that pleases everyone,” Castle said. “And [Interior will] do what they think they have the authority to do. But we all know that lawyers may disagree.”

His second option is a little more involved, but would also likely result in a lawsuit. There’s a catch with Interior’s power on the Colorado River. It is mostly able to make changes in the Lower Basin states of California, Arizona and Nevada.

If Interior wanted to act boldly and force cutbacks to water use, cuts would likely hit those states disproportionately.

“In either situation,” said Mike Connor, another former Reclamation commissioner. “Somebody is going to object and say, ‘You’re not acting consistent with the law’ and sue the Secretary to say ‘You made a bad decision.’”

Connor, who served from 2009 to 2014, said Interior’s authority has never been specifically defined, but it mostly comes from the 1928 Boulder Canyon Project Act. That legislation created Hoover Dam, which creates Lake Mead, and the All-American Canal, which supplies water to California’s Imperial Valley. That gives the federal government some control of the nation’s largest reservoir and the water supply for the Imperial Irrigation District, the river’s single largest water user.

There are a few other options besides Interior’s two paths, but they’re much harder to predict.

While states hold most of the planning power on the Colorado River, other big entities could try to go around them. For example, the water department in a major city, or a large farm group could use their big budgets and legal teams to influence lawmakers and get a form of Colorado River rules passed by the U.S. Congress.

States could also ask for an extension, kicking the can down the road by another year or two. The extended deadline could give them more time to coalesce around new rules, but policy experts say states should try to avoid that and agree on rules that are urgently needed to manage the shrinking river.

“That sort of takes the foot off the accelerator and we haven’t really done anything,” Castle said.

Will the states agree before the deadline?

There is at least some reason to believe the states will steer the Colorado River away from collapse or court. For all of their disagreements, state water negotiators do seem to be on the same page about one thing: keeping their situation out of the Supreme Court.

Amy Haas, executive director of the Colorado River Authority of Utah, told KUNC in February that it would be “folly” to take their negotiations to court.

“We are the ones who should really shape the outcome here,” she said. “We’re the experts. We’re the water managers. We understand the system. Why would we want to relinquish that control and that responsibility?”

States appear to be moving closer to implementing new Colorado River rules without any messy court battles. Early details of a proposal to distribute water cutbacks are emerging, and it appears that it could push states long mired in disagreement toward consensus.

Instead of those states leaning on old rules that don’t account for climate change, they’re proposing a new system that divides the river based on how much water is in it today.

State leaders were quick to emphasize that the plan is in its early stages, but cast it as a way to agree before the 2026 deadline.

“I was very pessimistic that we were on a path towards litigation,” said Tom Buschatzke, Arizona’s top water negotiator. “I’m more optimistic now that we can avoid that path if we can make this work.”

This story is part of ongoing coverage of the Colorado River, produced by KUNC and supported by the Walton Family Foundation.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline A deadline looms for a new Colorado River plan. What happens if there isn’t one? on Jul 5, 2025.

This content originally appeared on Grist and was authored by Alex Hager, KUNC.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.