Part of a three-story series on the fight for and rebuilding of Myanmar’s Kayah state following the 2021 coup. Read Part 1 and Part 2.

DEMOSO, Kayah state, Myanmar – As a young medical student in relatively cosmopolitan Yangon, “Dr. Tracy” dreamed of becoming a great surgeon, a living testament to the possibilities offered in a new, freer Myanmar. The 2021 military coup dimmed her personal ambition, but not her hopes for democracy for her country.

Tracy, 26, who asked to go by that name for security reasons, was among the young doctors and nurses that as members of the “white coat society” led protests against the military junta after it ousted an elected civilian administration in 2021. She’s now part of a smaller group who fled city centers in the country’s interior to move to border areas to assist rebels fighting the military.

“This coup is not fair, simply,” Tracy said, from one of the huts that make up the O-1 hospital campus within Demoso township in Kayah state. “I asked myself, do you accept it? My answer was no. So, I resist, resist and resist.”

Tracy has since completed her studies under a curriculum developed by an exile government made up in part by elected officials who managed to avoid arrest after the coup.

But she doesn’t have the time or the resources to become the specialist she envisioned. It’s enough to help treat the cases of malaria and tuberculosis in the rural population she serves or help mend the shattered limbs of the rebels in her care.

If she were still living in Yangon, not helping the cause by providing underground medical care, “that [would be] useless of me,” she said.

“I don’t like it.”

A taste of freedom

Tracy and her colleagues at O-1 grew up in a freer Myanmar than their parents had. A decade ago, military rulers seemed to set the country on a path of democratic reform. While Myanmar’s generals retained control of a number of seats in the Parliament and control over some of the country’s most important ministries, they agreed to share power with officials elected in a popular vote.

After a half of a century of tight-fisted military rule, the changes brought a host of new opportunities for their generation and a taste of what could be, said Dr. Yori, 29, who is also from Yangon and is now the deputy medical superintendent of O-1.

“We knew there were many things that we could achieve with our own civilization and our own people,” he said.

The coup threatened all the progress, they believe. And when a young medical student was killed at one peaceful demonstration directly after the coup, thousands of health care professionals took to the streets and refused to work as part of the civil disobedience movement. Many were arrested by the military.

In Yangon, Yori and Tracy were a couple (they’ve since wed) with a shared opposition to military rule. Fearing arrest, they both fled to Kayah after a few months. Yori’s initial intention was to join the People’s Defense Forces, militias that are fighting under the exiled National Unity Government.

“I didn’t want to fight with a syringe. I wanted to fight with a gun,” he said. But he soon realized his skills as a doctor were needed more.

Leaving a ‘privileged life’

O-1, like camps for internally displaced people it shares the hills of Kayah with, is a collection of corrugated steel, green tarpaulin and bamboo. After the hospital where Tracy and Yori initially worked was bombed twice, the wise decision was made to abandon it for a hidden location in the jungle.

Clean Yangon, an NGO, paid to build a new emergency ward, X-ray and laboratory, and rooms for recovering patients. A new ward for infectious diseases was being built when RFA visited recently. Generators provide light and power. There’s sporadic internet and good food in the commissary.

All things considered, though, it’s a far rougher existence compared with what many of the doctors and nurses are used to. The Yangon they knew offered air conditioning, international cuisine and new opportunities for women.

“Before the coup, we were [living] a very privileged life,” said Dr. Hazel, 27, Tracy’s older sister. “We were just going to university and to eat out, and we have nothing else to worry about.”

There are now four rebel hospitals in Kayah, including O-1, to treat the wounded and the sick. Six doctors work at O-1, supported by seven medical students and about 30 nurses.

Yori said it costs about 50 million kyat, or $24,000, to run O-1 each month. About 150 patients are treated in that span of time, on average. War-related traumas are treated for free. Most poor patients aren’t charged either. Patients and relatives also don’t pay for food in the commissary.

As deputy superintendent, Yori said he makes about 150,000 kyat a month, or around $33, which is about enough to cover his cigarette habit.

“We’re not doing this for money or fame,” he said.

The hospital is funded almost entirely by donations. After four years of war, fundraising is becoming more difficult, Yori said. That raises the stakes for the Interim Executive Council, or IEC, the rebel-formed state government trying to simultaneously meet the needs of Kayah citizens.

It’s a struggle. Only about 5% of O-1’s budget comes from the IEC. Yori said the council is offering to take over the hospital, but the doctors are insisting that it be able to cover the entire budget.

“If we are to be called a state hospital, we don’t want to fundraise anymore,” he said.

A wounded rebel

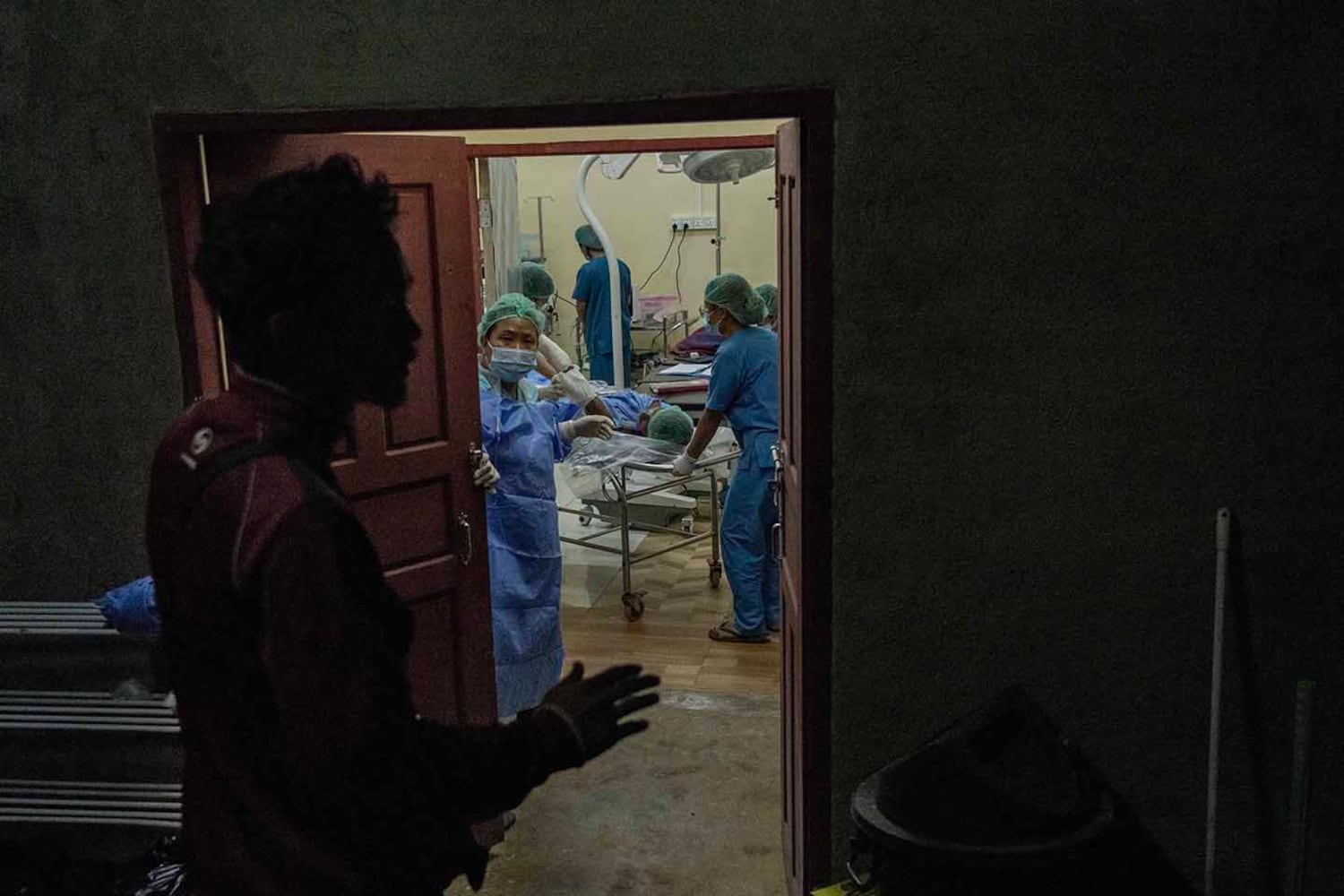

When RFA visited, a small group of Karenni Nationalities Defense Forces fighters waited nervously by a tunnel that led to an operating room, buried 18-feet underground to protect against airstrikes. The group had weary smiles of stained teeth from chewing betel and red eyes due to a fraught trip from the front.

In the damp operating room, Dr. Aung Ko Myint, 33, repaired what he could in a surgery that took about four hours with equipment from the old hospital and anesthesia and medicine smuggled in through military checkpoints. He had to amputate a part of each of his patient’s feet.

Aung Ko Myint said he hadn’t been trained as an orthopedic surgeon, but he’s picked up the skills in Kayah. Two days later, the young soldier, who uses the name Victorio, was up and smiling, describing how he had been wounded.

“The battle broke out in Khwee Htoe Lar village,” Victorio said. ”While transporting our injured comrade, we were attacked. Two of our comrades, who were riding a motorcycle, were shot dead.”

The shrapnel tore through Victorio’s legs and torso. It had taken weeks before his battalion members could clear a road from military troops in order to safely transport him to O-1.

Aung Ko Myint’s wife, Dr. Hnin Nu Nu Wai, 30, worked as an assistant surgeon at the East Yangon General Hospital before the coup but quit immediately after to participate in the civil disobedience movement.

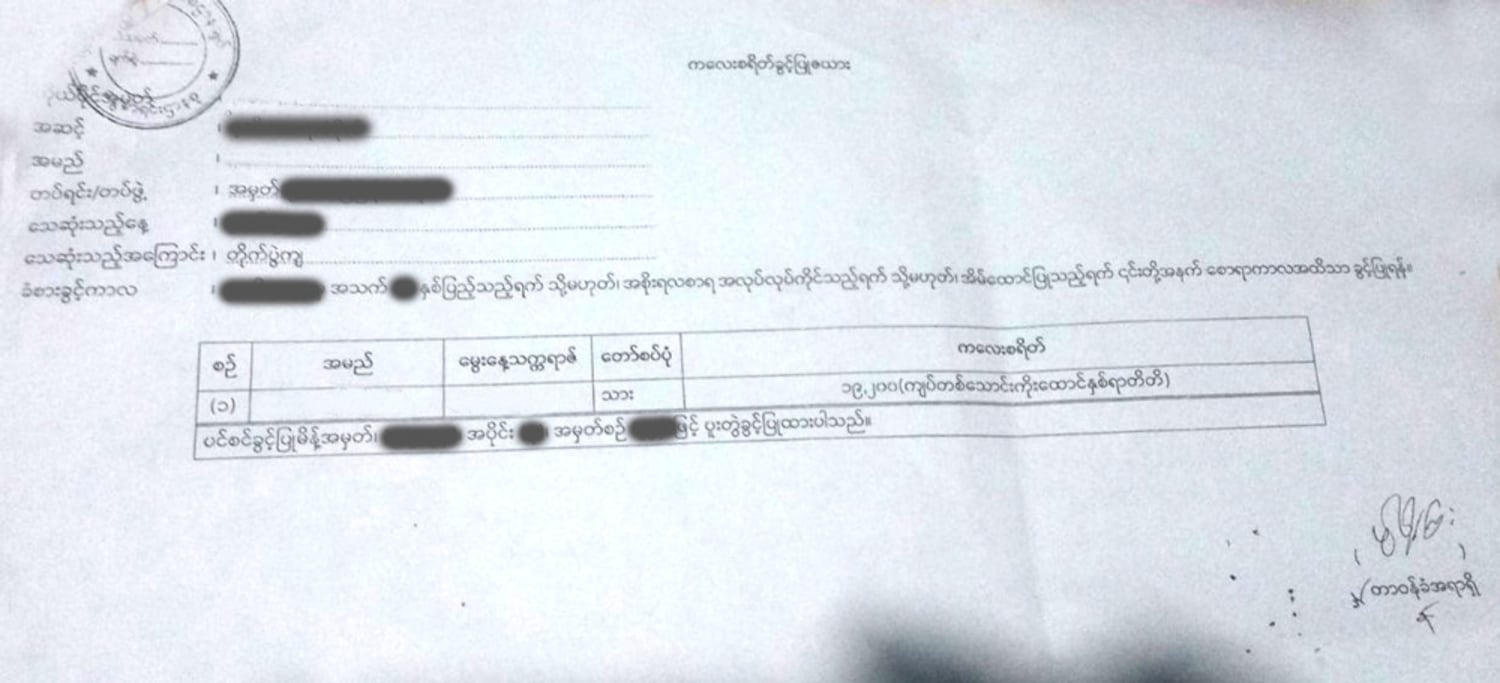

She was only able to come to Kayah last summer, however, because while treating rebels and locals in Karen state to the south, she was captured by military troops and charged with terrorism.

Hnin Nu Nu Wai spent two weeks in interrogation centers, before she was eventually sentenced to three years in prison. After treating female prisoners and prison staff and their families, however, she was given amnesty after two years and three months.

“I have so many nightmares,” she said. “That’s our life in Myanmar.”

Overcoming distrust

To cope with such traumas, the O-1 team say they rely on one another, commiserating over being separated from loved ones, the stresses of war and, not surprising for a group of young, ambitious people, nagging disappointment at watching the career advancement of former colleagues who stayed behind in military controlled areas.

“Now they are taking specialty courses, and meanwhile, we are in the jungle doing as much as we can,” said Arkar, a medical student training to be an orthopedic surgeon. “Everyone has their own choice. I don’t want to blame them. But for me, as a dutiful civilian, we should do the civilian disobedience movement.”

Beyond the difficulties presented by the war and limited resources, the doctors said initially they faced widespread distrust from the local population, many of whom practice Christianity instead of Buddhism.

Yori estimated that 90% of the doctors now working in the state are of Burmese origin, while Kayah state is a mix of ethnic groups collectively considered “Karenni.” They were naturally suspicious, associating the new arrivals with the military, also dominated by Burmese, that they have long suffered under.

As a gay man, Arkar, 26, said he feels particularly isolated at times. “Here it is very strict about that,” he said. “They never see two guys together in public.”

The lack of a social scene can compound his mental health struggles – he suffers from anxiety and bipolar disorders – as does being separated from his parents. He has access to a therapist, who recommended he write journals to help him deal with his new circumstances. In his small room a short walk to the hospital campus there is a stack of notebooks filled cover to cover with text and drawings beside his bed.

Despite it all, he’s here – “free and happy,” he says, to be serving the citizens and soldiers of Kayah.

“We are suffering so many injustices and painful moments, and so I guess that I should fight back for our country,” he said.

A birthday party

On a cool, wet night when RFA visited the staff gathered after hours to celebrate Dr. Hnin’s 30th birthday.

Doctors from other hospitals visited, as did medics at O-1 for training. Everyone swapped stories over river prawns, quail eggs and beef strips cooked over a small charcoal grill.

They kept the lights off so as not to attract attention from drones or planes overhead. Junta pilots can’t hear singing, however, so someone brought a karaoke machine for later when the case of beer grew more depleted.

Speaking to RFA, Dr. Tracy often punctuated a thought with a final “that’s all,” as in, “I decided to go to the liberated area to do what I can. That’s all.”

Though it may be a quirk of translating a thought into a language not native to her, it also seemed to reflect an unsentimental outlook, a straightforward faith that her decision to leave Yangon was the right one. Those qualities are shared by her colleagues, including her sister.

“Yes, there are slight difficulties comparing to my original lifestyle,” Hazel told RFA.

“I don’t think of things as sacrifices or something like that. They are my choices. I can participate in this revolution, and I can contribute something – maybe just a little – to my community or society.

“I’m really grateful for that.”

Edited by Boer Deng.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by Jim Snyder and Gemunu Amarasinghe for RFA.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.