This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by Radio Free Asia.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by Radio Free Asia.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Read RFA coverage of this topic in Burmese.

The dream of returning home to Myanmar remains uncertain for hundreds of thousands of Rohingya who fled to Bangladesh despite rebel control of the border, members of the ethnic group said Friday.

About 740,000 Rohingya fled from western Myanmar’s Rakhine state following a bloody crackdown against members of their stateless Muslim minority group in August 2017.

They joined other Rohingya who had settled in camps in and around Cox’s Bazar, bringing the total number of refugees in southeastern Bangladesh at the time to just over 1 million.

Years of negotiations to repatriate Rohingyas to Rakhine state have yielded little progress, in part because members of the community say their safety cannot be guaranteed back home after the military that targeted them seized power in a February 2021 coup d’etat.

On Dec. 8, rebels known as the Arakan Army, or AA, which is battling the junta for self-determination in Rakhine state, captured Maungdaw township and took control of the region’s border with Bangladesh.

The takeover rekindled hope that the Rohingya might be offered safe transport across the border and feel comfortable enough with AA governance to resettle their communities in Rakhine.

On Wednesday, the AA — which now controls about 80% of Rakhine state — announced that it would begin allowing people displaced by fighting to return home, after having fully secured the border.

RELATED STORIES

Almost 65,000 Rohingya have entered Bangladesh since late 2023, govt says

Rebels in Myanmar’s Rakhine state seize another stronghold, shun talks

Myanmar’s Rohingya suffer amid fighting

However, RFA Burmese spoke with Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh who said they remain uncertain about their return — in part because it’s unclear whether the AA might accommodate such a move and because ongoing fighting in Rakhine would leave them susceptible to military airstrikes.

“It is a time of war, so it is impossible for us to return home,” said Mohammed, a Rohingya refugee from Kutupalong refugee camp in Bangladesh. “Even if the AA takes over the entirety Rakhine state, our repatriation program remains far off because they are not a legitimate government.”

Refugees who earlier fled violence and persecution in Myanmar said they had been kidnapped and forced to fight in the country’s ongoing civil war for the Arakan Army as well as the junta.both the junta and the AA

Nearly 65,000 Rohingya have crossed into southeastern Bangladesh since late last year amid unrest and violence in Rakhine, according to Bangladeshi officials.

Even if the refugees are allowed to return home, they remain fearful of junta airstrikes, said Europe-based Rohingya activist Nay San Lwin.

“The repatriation program is directly related to the AA because they currently control the area [where the Rohingya communities are],” he said. “Even if the AA gives firm guarantees, the Rohingya people might suffer great losses if the junta carry out airstrikes when they return home. Their repatriation is largely concerned with their security.”

Demands for repatriation

Rohingya refugees have also demanded recognition of their identity as an ethnic minority of Myanmar, acknowledgment of their Myanmar citizenship and the opportunity to return home “with dignity.”

On Dec. 25, more than 100,000 Rohingyas in the Cox’s Bazar refugee camps protested and called for assistance from the international community, including the United Nations, in meeting their demands ahead of a return to Myanmar.

“When people in the camps return home, they hope to go back to their original homes,” said Mohammed of the Kutupalong refugee camp. “Moreover, we have also asked both Myanmar and international representatives to ensure our rights to freedom of movement, access to education, and all other basic rights. We will not change these demands.”

The AA’s seizure of the border has, in some ways, complicated the issue even further.

On Dec. 22, during a meeting on the situation in Myanmar, held in Thailand last month, Bangladesh Foreign Ministry spokesperson Mohammad Rafi Alam told reporters that the Bangladesh government had urged Myanmar’s junta to “find a way” to settle the border dispute as it would “not engage” with the AA.

A week later, however, Bangladeshi security experts, former diplomats and scholars advised the Bangladesh government to engage with the AA directly and diplomatically. The status of the relationship remains uncertain.

A former district law officer who asked not to be named due to security concerns told RFA that the repatriation of the Rohingyas will depend on the ruling administration in Rakhine state.

“Since there is currently no legal framework for the repatriation of the Rohingya, a bilateral agreement is essential for implementing this program,” he said.

On Dec. 23, nearly 30 Rohingya organizations worldwide called on the AA to guarantee the rights and security of all communities in Rakhine state, including the Rohingya; establish an interim consultative committee; recognize the Rohingya as an ethnic minority of Myanmar; and adopt and enforce a public code of conduct for AA fighters.

Attempts by RFA to contact AA spokesperson Khaing Thukha for comment on the Rohingyas’ return went unanswered by the time of publishing.

Dire food shortage

Meanwhile, more than 5,000 displaced Rohingya sheltering at a camp in Rakhine’s Pauktaw township are in urgent need of food after not receiving aid for more than a year, they told RFA on Friday.

A Rohingya at the camp in Pauktaw’s Ah Nauk Ye village said that the displaced are living on a diet of rice gruel, due to the food shortage.

“[Dry] rice is urgently needed at the camp as some displaced persons are suffering from starvation,” said the camp resident, speaking on condition of anonymity due to fear of reprisal. “We have no jobs and are forced to borrow money from others. The rising prices of essential goods are making our situation even more difficult.”

Camp residents said that a pregnant woman, an elderly person, and a child died in December due to a lack of access to healthcare and medicine, as well as malnutrition.

According to the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, Myanmar’s junta has restricted the delivery of food, medicine, and other relief items under its humanitarian assistance program to Rakhine state.

Moreover, local and international aid agencies have been blocked, and the United Nations Development Program warned in November that about two million people in Rakhine state could experience food shortage in March and April due to insufficient food supplies.

Attempts by RFA to reach Hla Thein, the attorney general and junta spokesperson for Rakhine state, for comment on the food shortages went unanswered Friday.

Translated by Aung Naing. Edited by Joshua Lipes and Malcolm Foster.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by RFA Burmese.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Read RFA coverage of this story here and here.

The death toll of political prisoners in the military junta’s prisons across Myanmar hit 31 in 2024 due to poor healthcare and inhumane treatment — nearly double the number of those who died for the same reasons in 2023, a year-end report by a political prisoners’ rights group says.

And their conditions are growing worse year by year in jails under the junta which seized power in a February 2021 coup d’etat, said the Political Prisoners Network-Myanmar, or PPNM, which monitors the situation inside the nation’s prison system, in the report issued Tuesday.

Of those who died, nine succumbed to unlawful torture and extrajudicial killings, both inside and outside the prisons, or were killed outside prisons, for political reasons and in response to protests against prison authorities, said PPNM committee member Theik Tun Oo.

Twenty-two others passed away because of inadequate health care, including the denial of urgent medical treatment and restricted access to public hospitals for so-called security reasons, he told Radio Free Asia.

Prominent political prisoners of the former National League for Democracy government — Zaw Myint Maung, chief minister of Mandalay region, and Win Khaing, minister of electricity and energy — both died in prison due to insufficient healthcare.

Last year, 17 political prisoners died from a lack of health care or human rights violations.

Female political prisoners

The report also noted that 42 female political prisoners were serving sentences across Myanmar at the end of 2024.

Among them were 35 mothers imprisoned with their children and seven pregnant women, though the actual numbers could be higher, the group said.

Some female political prisoners were knowingly arrested by the military junta during the coup while they were pregnant. Others were found pregnant after being taken to the prisons. Many of these women have since given birth in prison and are raising their babies behind bars.

Some children are suffering from mental and physical abuse in prisons, and lack access to nutritious food, Theik Tun Oo said.

“At present, children are exposed to the negative habits in the prisons, such as swearing and shouting, and they regularly have seen their mothers being abused,” he said.

Advocates for political prisoner are calling for the immediate release of pregnant women and mothers in jails with their children.

RFA could not reach junta spokesperson Maj. Gen. Zaw Min Tun for comment.

‘Brutal beatings’

In 2024, authorities also transferred about 1,800 political prisoners to correctional facilities far from their families, according to the report.

Former inmates said political prisoners were often moved to prevent them from protesting the suffering they experienced behind bars.

The father of a prisoner who was transferred to Tharyawaddy Prison in Bago region after serving a long-term sentence in Yangon’s Insein Prison on three political charges told RFA that he had difficulty getting a permit for jail visit.

Authorities arrested Naing Kyaw during the junta’s 2021 crackdown on young people protesting the coup in Yangon.

“He continues to suffer from internal injuries sustained during brutal beatings by the junta,” said his father.

RELATED STORIES

Over 100 Myanmar political prisoners have died since coup, group says

Myanmar insurgents free political prisoners in northern Shan state city

Guards beat dozens of female political prisoners in Myanmar

After a year of silence, 7 political prisoners confirmed killed in Myanmar’s Insein Prison

The father and some other relatives of other prisoners collectively hired a taxi to visit their jailed family members, with each having to pay about 20,000-30,000 kyats (US$9-14). He said he had to send daily necessities because of Naing Kyaw’s poor health.

RFA could not reach the office of deputy director-general of the Prisons Department for comment.

Legal rights denied

Myanmar’s Prison Act stipulates that political prisoners must be held in separate cells and are guaranteed full rights to medical care and family visits.

But legal experts have pointed out that following the military coup, such prisoners have been denied their legal rights and subjected to neglect.

“After 2021, prison management shifted to following orders from senior officials rather than adhering to prison laws and regulations,” a legal expert, who declined to be named for safety reasons, told RFA.

“Legal standards have been ignored, with junior officials, prison authorities and general staff merely implementing directives instead of upholding the law,” he said.

The Assistance Association for Political Prisoners, another organization that supports political prisoners in Myanmar, said on Oct. 7 that 103 political prisoners had died in prisons for various reasons since the coup d’état. Of that figure, 63 died due to a lack of sufficient medical treatment.

At year-end, the group documented nearly 21,500 political prisoners across Myanmar.

Translated by Aung Naing for RFA Burmese. Edited by Roseanne Gerin and Malcolm Foster.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by RFA Burmese.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Myanmar’s junta has enacted a cybersecurity law that will penalize unauthorized provision of virtual private networks, or VPNs, which many people use to circumvent internet restrictions to get access to news and information and to report on what is going on in their country.

The law, which came into effect on Wednesday, is aimed at preventing cyberattacks through electronic technology that threatens national sovereignty, peace, and stability, as well as to effectively investigate and bring charges against cybercrimes, the ruling military said in a statement published in newspapers.

Myanmar cracked down on the internet and the media after the military ousted an elected government in early 2021, sparking an armed uprising that has raised questions about the sustainability of widely unpopular army rule.

With the media under the control of the military largely a mouthpiece of the generals, many people rely on VPNs to skirt control and get access to independent and foreign media and to send material out of the country.

The law sets out a penalty of six months in prison and a fine for “unauthorized VPN installation or service.”

A VPN service provider told Radio Free Asia that the law could be disastrous for his business.

“It’s really bad for us,” said the service provider, who declined to be identified for security reasons.

“Even if there’s demand, we don’t dare sell it. We’ll keep an eye on whether they actually take action on it or not. If they really crack down on providing VPN service, we’ll have to register officially.”

The law also sets out jail for up to six months, and or a fine, for distributing, transferring, copying or selling information that is “inappropriate for the public” through electronic technology.

It also sets out jail of six months to a year for anyone found operating an illegal online gambling system. Illegal gambling, often organized by gangsters from China, has proliferated in more lawless parts of Myanmar and elsewhere in Southeast Asia.

RELATED STORIES

After 2024 setbacks, junta forces now control less than half of Myanmar

Acts of charity bring light to wartime Myanmar

Air, artillery strikes set grim benchmark for civilian casualties in Myanmar in 2024

A legal expert, who spoke on condition of anonymity for security reasons, told RFA that there should be a limit to the extent authorities can control online activity and the law posed a threat to public privacy and security.

“If these technologies are used for gambling or for criminal purposes, there needs to be a provision to take effective action. However, we see that the law’s intent is to harm the public’s security and privacy,” he said.

The law also states that Myanmar people living abroad can be punished.

“Myanmar citizens residing in foreign countries shall be liable to punishment under this law if they commit any offense,” according to a copy of the legislation published in newspapers.

Many Myanmar people living abroad try to report news from their country and organize opposition to the military via online communities.

Edited by RFA Staff.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by RFA Burmese.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Read RFA coverage of this topic in Burmese.

On the evening of Dec. 27, Myanmar’s military dropped a massive bomb on Pi King village in Shan state’s Pekon township, creating a crater as deep as a person’s height, according to a resident known as Panda.

“This is where the 500-pound bomb hit a residence and destroyed several other houses in this area,” said Panda who, like others interviewed for this report, spoke to RFA Burmese on condition of anonymity due to security concerns.

Three women were injured in the attack, he said.

The bombing is just the latest to have killed or wounded civilians this year as the military expanded its campaign of air and artillery strikes, amid growing losses by its ground troops to Myanmar’s myriad anti-junta forces.

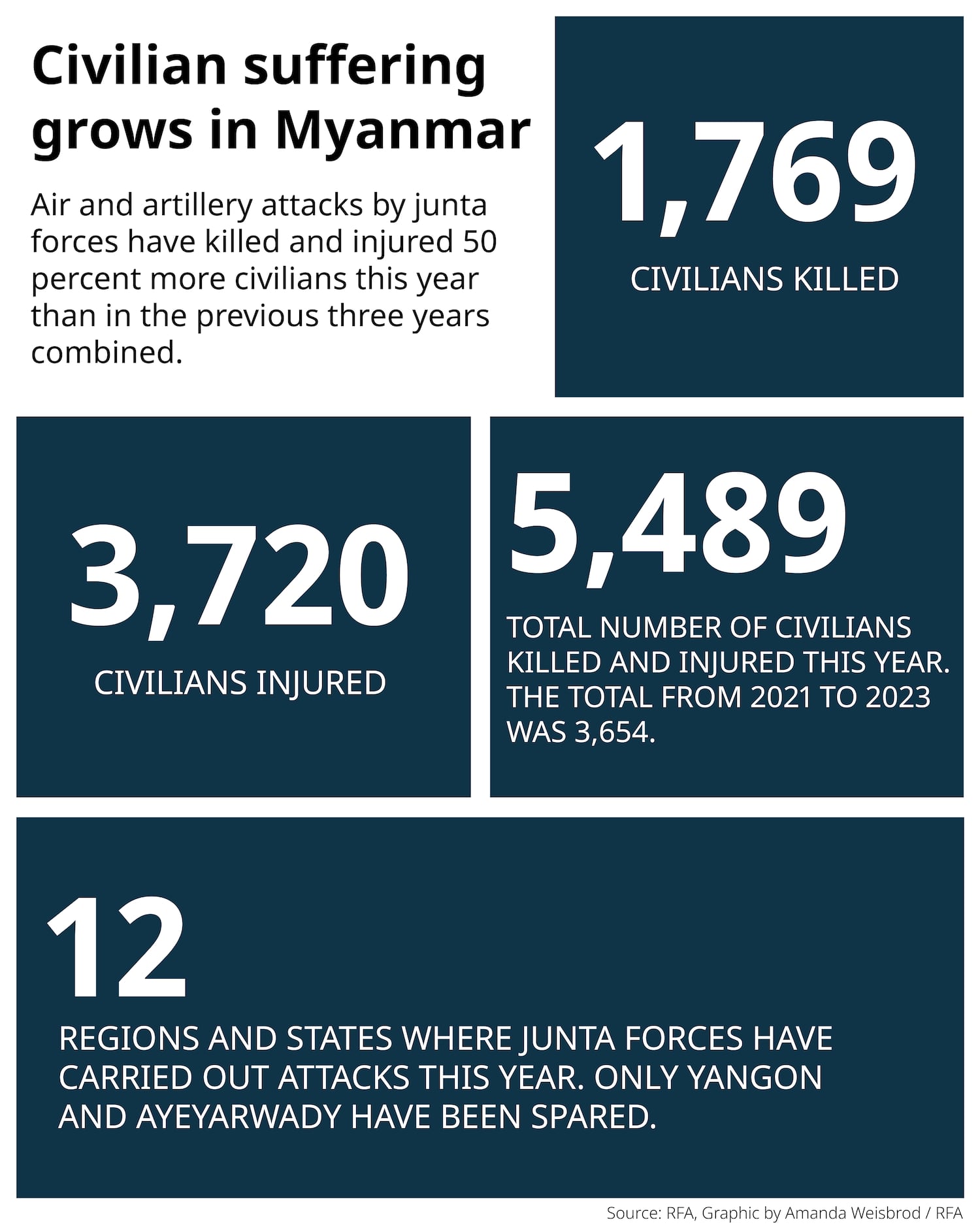

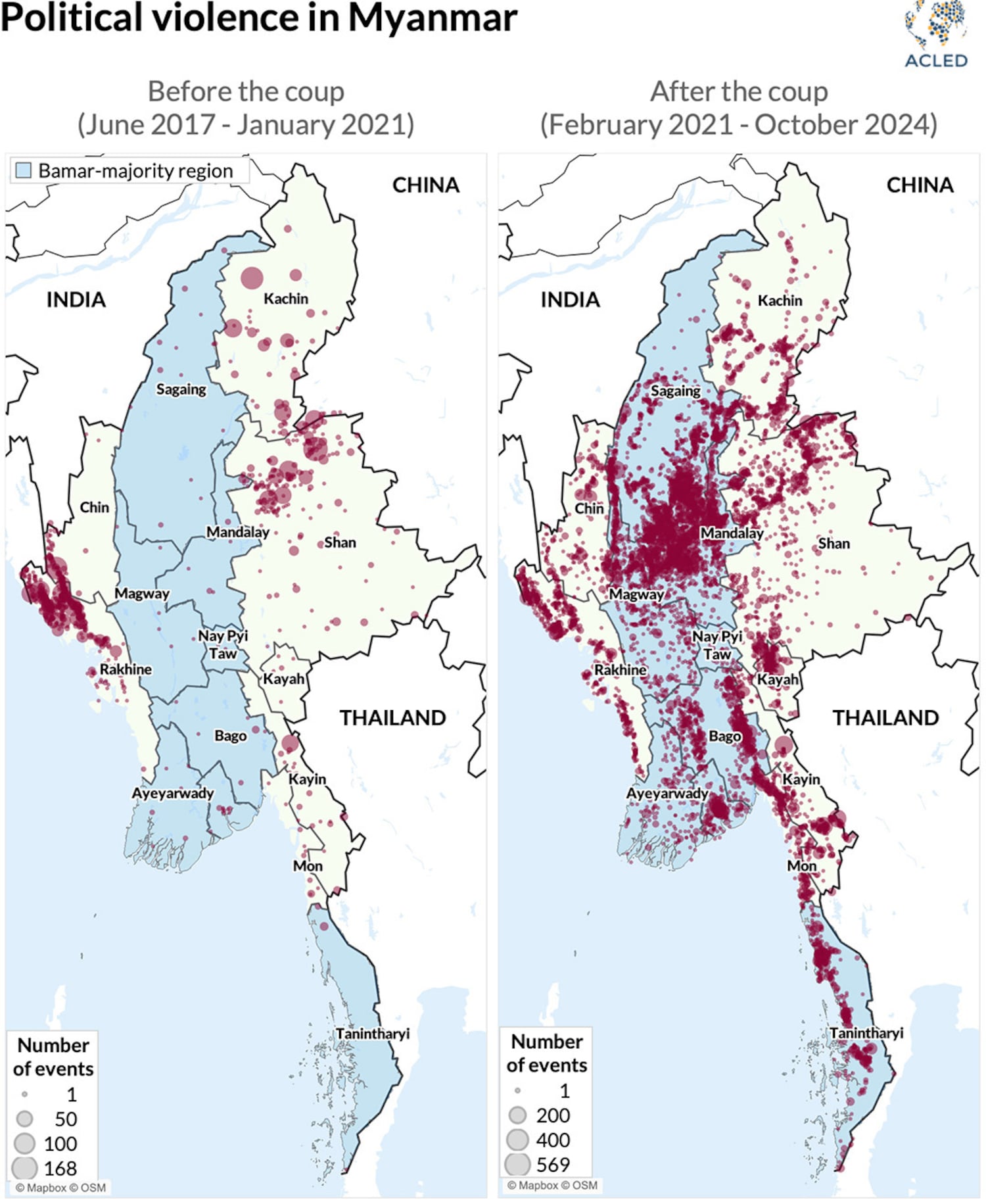

According to statistics collected by RFA, the junta carried out air and artillery attacks in 12 of Myanmar’s 14 regions and states in 2024, except for the regions of Yangon and Ayeyarwady, where the military has retained near-total control.

These attacks led to 5,489 civilian casualties — 1,769 deaths and 3,720 injuries — outpacing those of the previous three years combined and accounting for just over 60% of related casualties since the military seized power in a February 2021 coup d’etat.

In the three years from 2021 to 2023, junta air and artillery strikes killed 1,280 civilians and injured 2,374 others, for a total of 3,654 casualties.

The latest statistics follow a report by the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners (Myanmar), which said that at least 540 civilians were killed by junta airstrikes in the first 10 months of the year — mostly in western Myanmar’s war-torn Rakhine state.

The bombing of Pi King village took place just 11 days after evening airstrikes on Sagaing’s Yinmarbin township killed five civilians and seriously injured 10 others, despite a lack of fighting between the military and anti-junta groups at the time, according to an aid worker.

“Aircraft were frequently flying over the area, and residents were afraid of returning to their homes, so we could only begin rescue work at the break of day [on Dec. 17],” said Myat Ko of the Kani-Yinmarbin People’s Embrace Group. “Soon after, some injured people died at the hospital. Two had died on the spot [during the strikes].”

Sources from the township suggested that the junta had intentionally targeted civilians in the attack, given the absence of clashes, possibly for perceived ties between residents and anti-junta forces.

Losses mount despite shift

Col. Naw Bu, the spokesperson for the ethnic Kachin Independence Army, or KIA, one of the most powerful groups fighting the junta for self-determination in northern Myanmar’s Kachin state, said the increase in the number of related civilian casualties in 2024 was unsurprising, as “up to 80% of the junta’s attacks were conducted by air and artillery” in his region.

“It’s not easy for the junta to conduct a ground offensive,” said Naw Bu, whose KIA now controls more than 50% of Kachin state, including the entirety of the China-Myanmar border. “Instead, they are mainly using air and artillery. The junta is relying on [these types of] attacks.”

As anti-junta forces have gained experience and weaponry since the coup, they have presented an increasingly formidable challenge to the military’s ground troops.

RELATED STORIES

After 2024 setbacks, junta forces now control less than half of Myanmar

Junta airstrikes kill 540 Myanmar civilians since new year, mostly in Rakhine state

Myanmar Christians, wary of airstrikes, celebrate Christmas in a cave

Despite the military’s uptick in air and artillery strikes as a response, the junta lost control of 94 townships in 2024.

Several rebel groups recently told RFA that junta forces now control less than half the country after suffering major battlefield setbacks in 2024 — including the loss of command headquarters in Shan and Rakhine states.

Sgt. Zeya, a former air force officer now advising the opposition as part of the Civil Disobedience Movement of civil servants who left their jobs to protest junta rule, told RFA that the military might have suffered more setbacks this year if it hadn’t responded with increased strikes.

“If the junta hadn’t used artillery attacks and air strikes [to support its troops], the military would have lost 90% of its forces because the difference between the junta’s soldiers and our soldiers is their attitude and mentality,” he said. “They joined the military to seek more opportunities … They have no strong sense of ideology or patriotism, nor are they deeply tied to the military. No one wants to die fighting when this is the reality.”

More strikes anticipated in 2025

Observers told RFA that they expect the junta will expand its use of air and artillery attacks even further in 2025 as part of a bid to prevent further loss of territory.

Thein Htun Oo, executive director of the Thayninga Institute for Strategic Studies, run by former military officers, said the junta’s forces will “respond more aggressively” with strikes next year if the opposition forces continue their offensives.

Residents and rescue workers told RFA that civilian casualties are sure to increase if the attacks are intensified.

Aung Myo Min, human rights minister for Myanmar’s shadow National Unity Government, said that despite the NUG’s best diplomatic efforts to cut off the junta’s access to aircraft, fuel, and raw materials for the production of military weapons, “countries are still selling arms, both openly and secretly.”

“Some countries support democracy in Myanmar, but others are more interested in how they can benefit by cooperating with the junta,” he said. “We realize that a lack of effective action will cause people to suffer more and more.”

On Dec. 15 alone, the military commissioned six Russian-made Mi-17 helicopters, six Chinese-made FTC-2000G fighter jets, one K-8W fighter jet, and one Y-8 support aircraft.

According to Justice for Myanmar, which monitors conflict in the country, the military is predominantly receiving aviation fuel from China and Russia, while the junta has said that the raw materials it uses to produce military weapons come from 13 countries, including China, Russia and India.

Attempts by RFA to contact junta spokesperson Maj. Gen. Zaw Min Tun by telephone for comment on the military’s use of air and artillery strikes went unanswered by the time of publishing.

Translated by Aung Naing. Edited by Joshua Lipes and Malcolm Foster.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by RFA Burmese.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Nearly four years after the February 2021 military coup snuffed out an experiment in democracy and plunged an already poor country into deeper poverty, the people of Myanmar continue to suffer at the hands of a junta known for cruelty and mismanagement.

In a break from the relentless stream of headlines of aerial bombings of civilians, mass killings and other atrocities, RFA Burmese has documented efforts of ordinary people to help each other and their communities – and the outpouring of generosity they inspired.

An RFA Burmese story about a family-owned street restaurant offering meals to the urban poor for the equivalent of 33 U.S. cents went viral in early 2024, drawing more than 4 million views on Facebook, and tens of thousands of views on YouTube.

The video tripled the number of customers for the cheap meals, but it also tapped into the strong Burmese tradition of charity. Thousands of people came forward to donate money, rice and curry, and the property owner offered the family a larger space.

A video story about a young woman in Yangon who runs a roadside restaurant catering to working people drew nearly 2 million viewers on Facebook, and also went views on YouTube.

It also brought in a wave of hungry patrons. The influx of diners allowed Lu Lu, the restaurant owner to increase turnover and serve more working urban poor people.

Many of the half-million people who tuned into a video feature on an elderly couple in declining health eking out a living gathering and selling firewood did not stop at watching or sharing the report.

The couple, who had lost their only son in a storm at sea over 10 years ago, received a flood of donations of cash as well as cooking oil, rice, pepper, onions, salt, condensed milk and bread.

In a country where a third of the population needs humanitarian assistance after more than three years of civil war, more than a million viewers watched a four-minute profile of 11-year-old Pone Nyat Phyu helping her family make ends meet by weaving and selling mats in between her schoolwork.

A video feature on a family-owned business that employs more than 60 people making traditional handmade brooms for export drew 2.2 million views on Facebook in February –- leading to renewed interest in the products and job security for a workforce that supports hundreds of people.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by Paul Eckert for RFA.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Nearly four years after the February 2021 military coup snuffed out an experiment in democracy and plunged an already poor country into deeper poverty, the people of Myanmar continue to suffer at the hands of a junta known for cruelty and mismanagement.

In a break from the relentless stream of headlines of aerial bombings of civilians, mass killings and other atrocities, RFA Burmese has documented efforts of ordinary people to help each other and their communities – and the outpouring of generosity they inspired.

An RFA Burmese story about a family-owned street restaurant offering meals to the urban poor for the equivalent of 33 U.S. cents went viral in early 2024, drawing more than 4 million views on Facebook, and tens of thousands of views on YouTube.

The video tripled the number of customers for the cheap meals, but it also tapped into the strong Burmese tradition of charity. Thousands of people came forward to donate money, rice and curry, and the property owner offered the family a larger space.

A video story about a young woman in Yangon who runs a roadside restaurant catering to working people drew nearly 2 million viewers on Facebook, and also went views on YouTube.

It also brought in a wave of hungry patrons. The influx of diners allowed Lu Lu, the restaurant owner to increase turnover and serve more working urban poor people.

Many of the half-million people who tuned into a video feature on an elderly couple in declining health eking out a living gathering and selling firewood did not stop at watching or sharing the report.

The couple, who had lost their only son in a storm at sea over 10 years ago, received a flood of donations of cash as well as cooking oil, rice, pepper, onions, salt, condensed milk and bread.

In a country where a third of the population needs humanitarian assistance after more than three years of civil war, more than a million viewers watched a four-minute profile of 11-year-old Pone Nyat Phyu helping her family make ends meet by weaving and selling mats in between her schoolwork.

A video feature on a family-owned business that employs more than 60 people making traditional handmade brooms for export drew 2.2 million views on Facebook in February –- leading to renewed interest in the products and job security for a workforce that supports hundreds of people.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by Paul Eckert for RFA.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by Radio Free Asia.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Myanmar’s junta forces now control less than half the country after suffering major battlefield setbacks in 2024 -– including the loss of command headquarters in Shan and Rakhine states, several rebel groups said.

In June, the Three Brotherhood Alliance of ethnic armies resumed offensive operations in Shan state. Within weeks, the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army had captured Lashio, a city of 130,000 that is the region’s commercial and administrative hub and a gateway to China.

Another member of the alliance, the Ta’ang National Liberation Army, also seized the strategic Shan state townships of Nawnghkio and Kyaukme, as well as the gem mining town of Mogoke in neighboring Mandalay region.

Those victories in July and August left the junta with almost no territory in Shan state, a key area for border trade with China.

“The junta’s administration has completely ended here,” said a resident of Kutkai, a town in northern Shan state that has been the focus of junta airstrikes in recent months.

“At present, the economy and education sectors cannot function,” the resident told Radio Free Asia. “And the cost of living has skyrocketed.”

RFA couldn’t independently confirm the exact area lost by the military regime as the situation on the ground remains fluid and hard to verify given the constant fighting.

Junta spokesperson Maj. Gen. Zaw Min Htun didn’t immediately respond to RFA’s attempt for comment on Monday.

Election plans for 2025

The setbacks came as the junta regime moved forward with plans to hold an election in 2025, four years after they seized power in a Feb. 1, 2021, coup d’etat.

But opponents say the election would be a farce and simply a way of legitimizing their rule.

For starters, the vote would be held in just 161 townships controlled by junta authorities out 330 nationwide, Election Commission Chairman Ko Ko told political party representatives earlier this month.

Kyaw Zaw, a spokesperson for the shadow National Unity Government’s Presidential Office, told RFA that the military junta really only controls only about a third of the country, including the major cities of Yangon, Mandalay and the capital, Naypyidaw.

“But even in those areas, security is far from stable,” he said. “The regions controlled by rebel forces have expanded, increasing our responsibilities for providing public services.”

Local residents and insurgent forces said territory under junta control has declined in central Sagaing, Magway and Mandalay regions, where fierce fighting between the military and anti-junta forces has been constant since coup.

Ethnic rebel groups now also control large areas in Kachin state in the north and in Kayin state in the country’s east.

In Kayah state in eastern Myanmar, ethnic rebel groups have seized about 80% of the territory, according to Banyar Khun Aung, a vice secretary of the anti-junta Karenni State Interim Executive Council.

In each of the occupied cities in Kayah state, departments of administration, law and order, security, education, livestock, health and maternity and child care centers have been set up, he said.

“We have established administrative mechanisms in all the currently controlled areas,” he said.

Rakhine state

In Rakhine -– Myanmar’s westernmost state — the Arakan Army has captured 13 of 17 townships from the junta, a resident who requested anonymity for security reasons told RFA.

“Many areas of Sittwe city are already under their control,” he said. “Only Kyaukphyu, with Chinese investments, and the island town of Munaung are fully under the control of the military regime.”

Arakan Army fighters captured the junta’s western command headquarters in Ann township on Dec. 20.

Elsewhere in Rakhine, the military has been reinforcing troops in areas that it does control, residents said earlier this month. That includes Kyaukphyu, where China has plans for a port as well as energy facilities and oil and gas pipelines that run to its Yunnan province.

In neighboring Chin state, ethnic rebels captured two townships last week, Chin Brotherhood Alliance spokesperson Salai Yaw Mang said. Several anti-junta groups are now in control of about 85 percent of the state, he said.

Forced recruitment

In Shan state, to the northeast, ethnic armed groups control 24 townships, with just Tangyang, Mongyai and Muse still held by the junta. The capture of the northeastern command headquarters outside of Lashio in late July was one of the most significant losses for the military in years.

In total, ethnic armed groups and allied forces have seized 86 towns across the country, the Myanmar Peace Monitor of Burma News International reported on Dec. 23.

In Sagaing, in central Myanmar –- viewed as a homeland for the majority ethnic Bamar people –- a major junta offensive is expected sometime next year, according to Htoo Khant Zaw, a spokesperson for the People’s Defense Comrade group based in Sagaing’s Ye-U township.

“The regime is still forcibly recruiting young people, even in the cities,” he said. “They are providing training, and the offensive is expected to be launched by land and air in 2025.”

Translated by Aung Naing. Edited by Matt Reed and Malcolm Foster.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by Kyaw Lwin Oo for RFA Burmese.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Myanmar’s Arakan Army insurgents captured the west coast town of Gwa from the military, a major step toward their goal of taking the whole of Rakhine state, and then said they were ready for talks with the junta.

Gwa is on the coast in the south of Myanmar’s western-most state, 185 kilometers (115 miles) northwest of the main city of Yangon, and a gateway to the rice-basket Irrawaddy River delta.

The AA said their fighters took control of Gwa on Sunday afternoon as junta troops fled but the military was trying to counter-attack with the help of its air force and navy guns.

“The fighting is raging in some areas near Gwa. The junta council has sent reinforcements and they’re trying to re-enter,” the AA said in a statement late on Sunday.

Residents reported blazes in the town from junta artillery and airstrikes.

“Heavy weapons have landed in the town and everything is on fire,” said one resident who declined to be identified for safety reasons.

Early on Sunday, a barrage of small-arms fire was heard as the AA launched their push, followed by air attacks, the resident said.

“The small-arms fire has gone but now they’re bombing,” he told Radio Free Asia.

The AA said it believed 700 junta soldiers had been killed in weeks of battle for the town, based on bodies found, information from prisoners and documents seized. It did not give any information about casualties on its side or about civilian casualties.

It was not possible to independently verify the AA’s casualty figure and a spokesman for the junta that seized power in a 2021 coup did not respond to phone calls from RFA seeking comment.

All sides in Myanmar play up their victories and their enemies’ losses while minimizing their own in public statements.

The AA, one of Myanmar’s most powerful insurgent groups, has been accused of killings and other serious rights violations against the mostly Muslim Rohingya community. It denies that.

RELATED STORIES

Over one-third of Myanmar’s population to need aid by 2025: UNOCHA

Myanmar appoints new defense minister as army struggles

Myanmar to organize election in fewer than half of townships

‘Political means’

The capture of Gwa is another big step in a matter of days for AA troops, who are fighting for self-determination in Rakhine state.

They took a major military base in Ann town on Dec. 20 and have now captured 14 of the state’s 17 townships, pushing the military into shrinking pockets of territory.

The military is reinforcing its troops in the townships it controls – Sittwe, Kyaukphyu and Munaung, residents said this month.

Neighboring China has economic interests in Myanmar, among them plans for a port in Kyaukphyu, where it also has energy facilities, including oil and gas pipelines that run to its Yunnan province.

China, keen to end Myanmar’s conflict, has pressed two rebel groups in Shan state in the northeast to agree to ceasefires and talks.

The AA praised China’s “active leadership” in promoting border stability and said it would talk at any time.

“We always remain open to resolving the current internal issues through political means rather than military solutions,” the AA said.

It did not refer to a ceasefire and said it believed its offensive over the past year would contribute to the “liberation” of all of the oppressed Myanmar people.

The junta chief has also called for talks as his forces grapple with setbacks.

The AA said it recognized and welcomed any foreign investment that contributed to development and said it would take care of investors.

The Institute for Strategy and Policy (ISP-Myanmar), an independent research group, said this week that the AA controls 10 of the 11 Chinese projects in Rakhine state.

The fall of the state capital of Sittwe to the AA would represent the end of military rule there, political analyst Than Soe Naing told RFA

“Then the AA will have to talk about issues related to China’s interests,” he said.

Edited by RFA Staff.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by RFA Burmese.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Nearly 65,000 Rohingya have crossed into southeastern Bangladesh since late last year amid unrest and violence in Rakhine, their home state in neighboring Myanmar, according to newly updated information from Bangladeshi officials.

The new arrivals, documented from November 2023 to December 2024, add to a huge population of Rohingya refugees, who have been sheltering at sprawling camps and settlements in Cox’s Bazar district for at least seven years.

Bangladeshi authorities say they are set to collect biometric data from the newcomers, who number about 64,700 people, or some 17,480 families.

“The government has principally agreed to issue biometric identification for the newly arrived Rohingyas. It found the number to be around 60,000 after [a] head count,” Mohammed Mizanur Rahman, commissioner of the Refugee Relief and Repatriation Commission (RRRC) Office, told BenarNews on Thursday.

The Rohingya entered Bangladesh despite declarations from the previous government that it wouldn’t allow any more Rohingya into the country and it had sealed the borders to them.

The previous government, led by Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, fell in August 2024 under pressure from a student-led uprising. A transitional government has been in charge of Bangladesh since then.

However, details have not yet been released about the biometric identification system, which is set to start next month.

Human rights advocates had earlier raised concerns that the biometric details of Rohingya refugees – which may include fingerprints, facial and iris scans, as well as personal data – would be shared with Myanmar’s ruling junta without their consent or knowledge.

The biometric identification process would begin as soon as the government approves it, according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, or the UNHCR, which is involved in the activity.

“The Biometric Identification Exercise is not a registration, but will allow UNHCR to de-duplicate individuals who were counted more than once during the headcount, as well as exclude already-registered refugees who arrived in 2017 and who may have been counted,” the U.N. agency said in a statement sent to BenarNews.

About 740,000 Rohingya fled from Rakhine following a bloody crackdown against members of their stateless Muslim minority group in August 2017. They joined other Rohingya who had settled in camps in and around Cox’s Bazar, bringing the total number of refugees in southeastern Bangladesh at the time to just over 1 million.

In June 2021, Human Rights Watch accused UNHCR of “improperly” collecting and sharing personal information from the Rohingya refugees with the Bangladeshi government, which shared them with the Myanmar junta.

“The agency did not conduct a full data impact assessment, as its policies require, and in some cases failed to obtain refugees’ informed consent to share their data with Myanmar, the country they had fled,” HRW alleged.

In response, UNHCR said it had followed proper procedures in its biometric data collection system.

Rakhine’s deteriorating situation

Bangladeshi authorities fear there may be a spike of Rohingya refugees fleeing from Rakhine as the situation in the Myanmar state continues to worsen.

“The recent influx was triggered [by the takeover] of Maungdaw township in Rakhine by the Arakan Army [AA],” the RRRC commissioner said.

There have also been incidents of Rohingya villages being razed, forcing residents to take shelter across the border, he also said.

This month, ethnic minority AA insurgents – which are fighting for self-determination in Rakhine state – said they had captured a major military base in the town of Ann.

The AA’s capture of the base was the latest major setback for the Burmese junta, which seized power in a February 2021 coup.

Refugee Zahangir Alam told BenarNews that AA members were taking many young Rohingya captive.

“The Arakan Army’s torture [of] Rohingya is more agonizing than that of Myanmar Army. I used to study at an educational institute there in Maungdaw and had to flee to save myself from their torture. My younger brother is still held hostage in the camp run by the Arakan Army,” Zahangir said.

Refugees who earlier fled violence and persecution in Myanmar said they had been kidnapped and forced to fight in the country’s ongoing civil war for both the junta and the AA.

With the help of a smuggler, also known as a “broker,” Zahangir was able to flee to Bangladesh. He is currently staying at a refugee camp in Cox’s Bazar.

Bangladeshi authorities said smugglers had been helping Rohingya – in exchange for hefty fees – to cross the border areas between southeastern Bangladesh and northwestern Myanmar.

Some refugees claimed they had to pay smugglers bribes ranging from Tk 20,000 (U.S. $166) to Tk 25,000 ($200) to cross the border.

If the situation further deteriorates, there may be more Rohingya fleeing into Bangladesh, foreign ministry official Ferdousi Shariar and foreign affairs adviser Md. Touhid Hossain said.

Amid the unrest in Myanmar, Bangladeshi authorities said they were closely watching the border areas at the town of Teknaf and Saint Martin’s Island.

RELATED STORIES

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by Abdur Rahman and Mostafa Yousuf.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

The Myanmar military has razed villages north of the city of Mandalay after insurgents who had been threatening to attack the country’s second biggest city from the area withdrew, a research group and residents said, apparently aiming to ensure the area cannot be re-occupied.

Forces of the junta that seized power in 2021 have been on the back foot for most of this year, losing large amounts of territory to ethnic minority insurgents, while allied pro-democracy fighters have made unprecedented gains in central areas including the Mandalay region.

But the junta has since November mobilized forces for offensives in Mandalay as well as the central areas of Sagaing and Magway, helped by ceasefires that two main insurgent groups in Shan state struck after they came under pressure from neighboring China to make peace.

The research group Data for Myanmar said junta forces had razed eight villages in Madaya township, just 25 kilometers (15 miles) to the north of Mandalay city, and one in nearby Thabeikkyin township.

Residents said large deployments of troops were putting everything to the torch in the villages that have mostly been abandoned by their thousands of residents.

“Villages are being burned until everything is gone. Troops go to the villages one after another and burn everything,” a resident of Madaya township told Radio Free Asia on Friday.

Residents were too frightened to think about going back, the resident said.

“No one can get close to check on their homes because the troops are still there,” said the resident who declined to be identified in fear of reprisals.

The villages had been occupied by members of pro-democracy militias known as People’s Defense Forces, or PDFs, that sprang up after the 2021 coup to fight to end military rule in collaboration with ethnic minority insurgents based in border regions.

PDFs have attacked the military relentlessly in central areas this year, taking over territory even on the approaches to Mandalay and the nearby garrison town of Pyin Oo Lwin, home to the military’s Defense Forces Academy.

But the military has been pushing back in the dry season, which began in November and traditionally favors the army that can transport its heavy equipment and supplies to more remote regions on dried-out roads.

Data for Myanmar said in a report on Thursday that the eight villages destroyed in the west of Madaya township included Mway Ku Toet Seik, Mway Thit Taw Yone, Mway Pu Thein, Thu Htay Kone and Mway Sin Kone.

In Thabeikkyin township, troops torched hundreds of homes in Twin Nge village, the group said.

PDF fighters had abandoned all of their positions in the villages before the troops began the sweep, residents said.

RFA tried to contact the spokesman for the military in the Mandalay region, Thein Htay, to ask about the situation but he did not respond.

Data for Myanmar said in November that 105,314 houses had been burned down across the country since the 2021 coup.

The conflict is causing a humanitarian crisis, compounded by disastrous flooding this year.

The United Nations says about a third of Myanmar’s population, or 18.6 million people, are in humanitarian need with children bearing the brunt of the crisis with 6 million of them in need as a result of displacement, food insecurity and malnutrition.

Edited by RFA Staff.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by RFA Burmese.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Many members of Myanmar’s Christian minority celebrated Christmas in fear this year, worried that the military would unleash airstrikes on them, with some worshippers taking to the safety of a cave deep in the forest for Christmas Eve mass.

Predominantly Buddhist Myanmar has been engulfed in conflict since the military overthrew an elected government in 2021, with fighting particularly heavy in ethnic minority areas where many Christians live and where generations have battled for self-determination.

“Christmas is a very important day for Christians, it’s also important to be safe,” said Ba Nyar, an official in an ethnic minority administration in eastern Myanmar’s Kayah state in an area under the control of anti-junta insurgents.

“That’s why lately religious ceremonies have only been held in Mother’s Cave, which is free from the danger of air strikes,” he told Radio Free Asia, referring to a cave in the forest that covers the state’s craggy hills near the border with Thailand.

Several hundred people, most of them women and children, crowded into the cave on Christmas Eve, squatting on its hard-packed floor for a service led by a priest standing behind an altar bedecked with flowers and candles.

Ba Nyar and other residents of the area declined to reveal the cave’s location, fearing the junta would bomb it with aircraft or attack drones if they knew where it was.

Most of those attending the service in Mother’s Cave have been displaced by fighting in Kayah state, where junta forces have targeted civilians and their places of worship, insurgents and rights groups say.

Nearly 50 villagers were killed in Kayah state’s Moso village on Christmas Eve in 2021, when junta troops attacked after a clash with rebels.

In November, the air force bombed a church where displaced people were sheltering near northern Myanmar’s border with China killing nine of them including children.

More than 300 religious buildings, including about 100 churches and numerous Buddhist temples, have been destroyed by the military in attacks since the 2021 coup, a spokesman for a shadow government in exile, the National Unity Government, or NUG, said on Tuesday.

RFA tried to contact the military spokesman, Major General Zaw Min Tun, for comment but he did not answer phone calls. The junta rejects the accusations by opposition forces and international rights groups that it targets civilians and places of worship.

About 6.5% of Myanmar’s 57 million people are Christian, many of them members of ethnic minorities in hilly border areas of Chin, Kachin, Kayah and Kayin states.

No Christmas carols

In northwestern Myanmar’s Chin state, people fear military retaliation for losses to insurgent forces there in recent days and so have cut back their Christmas festivities.

“When the country is free we can do these things again. We just have to be patient, even though we’re sad,” said a resident of the town of Mindat, which recently came under the control of anti-junta forces.

“In December in the past, we’d hear young people singing carols, even at midnight, but now we don’t,” said the resident, a woman who declined to be identified for safety reasons.

“I miss the things we used to do at Christmas,” she told RFA.

In Mon Hla, a largely Christian village in the central Sagaing region, a resident said church services were being kept as brief as possible.

Junta forces badly damaged the church in the home village of Myanmar’s most prominent Christian, Cardinal Charles Maung Bo, in an air raid in October.

“Everyone going to church is worried that they’re going to get bombed,” the resident, who also declined to be identified, told RFA on Christmas Day.

“The sermons are as short as possible, not only at Christmas but every Sunday too,” she said.

The chief of the junta, Senior Gen. Min Aung Hlaing, attended a Christmas dinner on Sunday at St. Mary’s Cathedral in the main city of Yangon and reiterated a call for insurgents to make peace, saying his government was strengthening democracy.

Anti-junta forces dismiss his calls as meaningless and say there is no basis for trusting the military, which overthrew a civilian government in 2021, imprisoned its leaders and has tried to crush all opposition.

Edited by RFA Staff.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by RFA Staff.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

From an exuberant mountaineering woman to a boy representing unheard refugees, here are some of the brave individuals that gave us hope

Nine years ago, Cecilia Llusco was one of 11 Indigenous women who made it to the summit of the 6,088 metre-high Huayna Potosí in Bolivia. They called themselves the cholitas escaladoras (the climbing cholitas) and went on to scale many more peaks in Bolivia and across South America. Their name comes from chola, once a pejorative term for Indigenous Aymara women.

Read more on this topic in Burmese.

Ethnic Chin and Rakhine rebels now control 85% of western Myanmar’s Chin state and expect to seize control of another key township from the country’s military soon, a Chin official said Monday.

Fighting in Chin has escalated in recent months, as rebels seek to remove junta forces that occupied the state following the military’s February 2021 coup d’etat.

Salai Yaw Mang, the spokesperson of the Chin Brotherhood Alliance, or CBA, said his group is in control of Mindat, Matup and Kanpetlet — three of Chin state’s nine townships — while the Chinland Defense Force, or CDF, controls the township of Tonzang.

The ethnic Rakhine Arakan Army, or AA, controls a fifth township — Paletwa — leaving only the townships of Tidim, Thantlang, Hakha and Falam under junta control, he said during a press briefing on Monday.

All told, rebels now occupy 85% of Chin state by land area, said Salai Yaw Mang, adding that the CBA “expect[s] Falam will be liberated soon.”

“So, there are four towns under the junta, and we are conducting an offensive against [Falam],” he said. “It can be said that 80-85% of Chin state has been completely liberated.”

The CBA now controls all of Falam except for the junta’s Infantry Battalion 268, based on the outskirts of the town, he said.

Seizing Kanpetlet and Mindat

Salai Yaw Mang’s comments followed the CBA’s announcement on Sunday that it was launching an offensive to seize Kanpetlet, prompting junta troops to flee and the CBA to take control, according to CDF forces in the township.

RELATED STORIES

Myanmar rebels capture major military base in west, group says

Insurgents in Myanmar’s Chin state capture four military camps, group says

Myanmar junta chief urges peace after troops suffer setbacks

Salai Aung Lein, the chief of the CDF Kanpetlet, said that his forces are hunting down the fleeing junta troops.

“While preparing to take control of the town, we surrounded it for about five months, systematically weakening their forces,” he told RFA Burmese. “Just as we were about to launch a major offensive, they fled from Kanpetlet. We are now tracking down the escapees.”

Salai Aung Lein said the CDF in Kanpetlet rescued a junta soldier who was shot and arrested by his fellow troops as he tried to flee, as well as two political prisoners and four other prisoners held at the town’s police station.

Meanwhile, the CDF in nearby Mindat recently announced that residents will be allowed to return to their homes there and in Kanpetlet “once landmines have been cleared” and the towns are fully secured.

Last week, the CDF and allied fighters seized military and police strongholds, administrative offices and other buildings in Mindat, which they began attacking on Nov. 9 as part of an offensive known as “Operation CB.” The group said 123 junta soldiers had surrendered and that it had rescued 13 political prisoners during the takeover.

CDF Mindat Chief of Staff Salai Thang Chune Pe said his group is “well-prepared” to maintain control over the town.

“Capturing a town is easy, but maintaining control over it is far more challenging,” he said. “We have extensive plans for construction and rebuilding … We are working diligently to secure the town and ensure it does not fall back into enemy hands.”

Residents still displaced

Residents of Mindat and Katpetlet told RFA that the military dropped bombs on the towns on Sunday.

CDF Mindat issued a statement on Monday advising people to avoid the town due to “ongoing junta airstrikes.”

A displaced resident of Mindat said he plans to return home as soon as possible.

“We’ve faced various challenges as displaced persons,” he said, speaking on condition of anonymity to avoid reprisal. “If possible, we want to go back home immediately. We’d return tomorrow if the relevant armed groups give us approval.”

Attempts by RFA to contact Aung Cho, the junta’s spokesperson for Chin state, by telephone for comment on fighting there went unanswered.

The CBA’s Salai Yaw Mang told RFA that capturing the towns of Mindat and Kanpetlet will “open up [trade] routes to Bangladesh and India,” which Chin state borders, and boost the local economy.

He added that control of the townships is “strategically important” as rebel groups turn their attention to neighboring Magway region.

The CBA has said it aims to strengthen its relationship with India following its successful occupation of Chin towns along the border.

Translated by Aung Naing. Edited by Joshua Lipes and Malcolm Foster.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by RFA Burmese.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Myanmar’s junta has been mobilized forces for offensives in the Mandalay, Sagaing and Magway regions at the same that it has significantly reduced attacks in northern Shan state following a recent ceasefire there, members of the rebel People’s Defense Forces told Radio Free Asia.

Between Dec. 2 and Dec. 6, junta airstrikes and artillery killed 19 people and wounded at least 10 others in three townships in Mandalay region’s Myingyan district, according to an official from a pro-democracy paramilitary People’s Defense Force, or PDF, who requested anonymity for security reasons.

Among the dead were four rebel paramilitary fighters, the PDF official said.

The attacks are likely inspired by the junta’s larger aim of regaining control of Myanmar’s central plain heartland, according to the PDF official. The central plains -– home to the country’s majority ethnic Bamar peoples –- has seen fierce fighting since the military’s Feb. 1, 2021, coup.

PDF units are made up of ordinary civilians who took up arms against the junta following the coup, and in many areas they have pushed junta troops back from territory the controlled.

The offensives also coincide with the recent ceasefire agreed to by the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army, or MNDAA, and the Ta’ang National Liberation Army, or TNLA, after pressure from neighboring China.

“China’s interference has played a significant role in Myanmar’s overall military situation,” a PDF member in Magway region’s Pakokku township said.

“While the TNLA and MNDAA in northern Myanmar are facing pressure from China, the junta has reduced its airstrikes, and battles have decreased in these areas,” he said. “This has led the junta to focus more on the plains.”

The attacks have notably increased in Mandalay, Sagaing, and Magway regions since just after junta chief Min Aung Hlaing returned from his early November trip to China, according to local rebel fighters.

Resistance forces have abandoned some road sections between Myingyan and Taungthar townships in Mandalay due to the junta’s intensive ground and air attacks, according to the PDF official in Mandalay region’s Myingyan district.

The junta has also moved forces into Sagaing region’s Pinlebu township, and have also sent troops along the Ann-Padan route, which is the only connection between Ann town in Rakhine state and Padan in Magway region, the official said.

“They are likely preparing to control the central plain areas of Myanmar through a defensive war strategy,” the PDF official said.

Political analyst Than Soe Naing said the last few weeks have again highlighted how anti-junta forces need to improve on their military strategy and coordination in central Myanmar.

“Without a united front in the plain areas, their offensives have slowed, and they still require more weapons and ammunition,” he said.

RFA attempted to contact junta spokesperson Maj. Gen. Zaw Min Tun to ask about the military offensive in the central plains region, but received no response.

Translated by Aung Naing. Edited by Matt Reed and Malcolm Foster.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by RFA Burmese.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Read RFA coverage of this topic in Burmese.

Myanmar’s junta appointed a new minister of defense, state-controlled media reported, in the wake of significant insurgent advances across the county that have put the military under unprecedented pressure.

Gen. Maung Maung Aye, who has been chief of general staff, was appointed minister in place of Gen. Tin Aung San, who retained his position as deputy prime minister, media reported.

State media did not give a reason for the change in its reports on Wednesday but the military has suffered major setbacks at the hands of insurgent forces over the past year.

RFA called junta spokesperson Maj. Gen. Zaw Min Tun for comment, but he did not respond by time of publication.

A defense official in a parallel government in exile, the National Unity Government, or NUG, said the junta would be determined to change the trajectory of the war.

“Across the whole country, the army is obviously losing very badly, so this could be to redeem themselves or change that,” said NUG defense official Aung San Sha.

The new defense minister will have to deal immediately with a crisis in Rakhine state in the west, where ethnic minority Arakan Army insurgents are closing in on the military’s Western Command headquarters in the town of Ann.

The loss of the base will be a major setback for the army against one of Myanmar’s most powerful guerrilla forces.

Ethnic Kachin insurgents are battling to capture the northern town of Bhamo, while fighters in the northwest, central areas and the east have also made advances.

RELATED STORIES

Junta chief vows to complete Myanmar census by year-end — then hold elections

Myanmar rebels capture last military post on Bangladesh border

Myanmar military presses offensive after two groups agree to talk

In Shan state in the northeast, insurgents captured the town of Lashio, on an important trade route to the nearby border with China, in August and have held on to it despite a relentless campaign of airstrikes by the military.

China has pressed two insurgent armies in Shan state to talk peace with the junta but it is not clear if the rebels will withdraw from the places they have captured, including Lashio.

The new minister will be responsible for providing security for an election expected next year, which the junta hopes will boost its legitimacy, both at home and abroad, even though the opposition has rejected the vote as meaningless when their leaders, including Aung San Suu Kyi, are in prison.

A former soldier who defected to the ranks of the junta’s opponents said the outgoing minister was also paying the price for implementing a deeply unpopular campaign of conscripting young people, with nothing to show for it.

“All over the country the military is suffering – they’re recruiting and aren’t succeeding,” said the defector, Naung Ro. “It’s also because of this that Tin Aung San has been replaced,”

Maung Maung Aye will be the third defense minister appointed by the junta that seized power with the ouster of an elected government in February 2021.

Translated by Kiana Duncan. Edited by RFA Staff.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by RFA Burmese.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

After the 1962 coup in Myanmar (then known as Burma), one of the first steps taken by General Ne Win was to “revamp and reorganise” the country’s military intelligence apparatus. According to the British writer Harriet O’Brien, the Directorate of Defence Services Intelligence (DDSI), widely known as the Military Intelligence Service (MIS, or simply “the MI”) was Ne Win’s “special creation”. A program was implemented to:

Expand and retrain the military intelligence forces … The MI became increasingly powerful and their operations gradually extended beyond merely gathering information to assist troops fighting the insurgent armies … They became a network of spies, a powerful secret police force monitoring the activities of ordinary people.

Ne Win’s inspiration for an expanded military intelligence organisation with a broader remit is popularly believed to be the Japanese Kempeitai military police, from which it is said the old dictator received intelligence and counter-espionage training during the Second World War.

Hard evidence to support this claim, however, is difficult to find. It raises the question of whether this is another case of the conventional wisdom with regard to Myanmar winning out over careful research. A quick historical survey might help clarify matters.

Colonel Keiji Suzuki, the Japanese spy sent to Rangoon in 1940 to recruit young Burmese nationalists for the coming war against the British, was assigned by the Second Bureau (Intelligence) of the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) General Staff. According to Kyi Win Sein, Ne Win studied for a short period at the Nakano School in Tokyo with four other members of the group known as the “Thirty Comrades”. The Nakano School was the IJA’s main training centre for military intelligence, counter-intelligence and unconventional warfare. Also, in 1941 the group’s army instructors on the island of Hainan were usually Nakano School graduates.

This has led James McAndrew, Bertil Lintner and other Myanmar-watchers to assume that the Kempeitai trained Ne Win. The Japan-based scholar Donald Seekins also seems to have conflated the Nakano School with the Kempeitai. He has suggested that “the sophisticated Military Intelligence apparatus [Ne Win] established after Burma became independent may owe something to his Japanese teachers”. In his comprehensive biography of Ne Win, Robert Taylor does not refer to this reported intelligence training, apparently because he found no evidence to warrant mentioning it.

The issue is relevant as a number of scholars and other commentators have claimed that, after seizing power in 1962, Ne Win was keen to “break with the British tradition and turn the intelligence apparatus into a secret police along the lines of the Kempeitai or Germany’s efficient Geheime Staatspolizei (Gestapo)”.

According to Kin Oung, for example, in the early 1970s DDSI chief “MI” Tin Oo was encouraged by Ne Win not just to collect military intelligence, which had been the main focus of his predecessors, but to create a secret police force that could monitor and control the civilian population. Tin Oo was also charged with keeping a close eye on the armed forces (Tatmadaw), the loyalty and cohesion of which was crucial for the regime’s survival. Thus, wrote Kin Oung, “the Kempeitai tradition was reborn”.

Allusions to the DDSI’s supposed Kempeitai antecedents have also been made by sundry politicians, activists and human rights campaigners. They have been keen to blacken the name of Myanmar’s modern intelligence apparatus by linking it to the reviled Japanese military police force, which in 1945 was described by the US Office of Strategic Studies as “the most powerful, the most hated, and the most feared organisation in Japanese-occupied territory”.

The critical question here is whether the Burmese received intelligence training from the Kempeitai, or from members of the IJA’s intelligence corps. The latter seems to be the case. The Nakano School was not under the control of the Kempeitai, which had its own dedicated training facilities. The School taught courses in intelligence and counter-espionage, subjects that also fell within the responsibilities of the Kempeitai, but there is no evidence that Ne Win or any other members of the Thirty Comrades were trained in intelligence matters by the military police.

All that said, the Japanese roots of Myanmar’s military intelligence organisation remain unclear. Burmese servicemen received instruction in relevant subjects from Japanese officers after the creation of the Burma Independence Army (BIA) in 1941 and the Burma Defence Army (BDA) in 1942. After nominal independence was granted to Burma by the Japanese in 1943, the Burma National Army (BNA) too received training from the Japanese, both in Burma and Japan. During this time, Japanese military doctrine was doubtless absorbed by members of the nascent Tatmadaw, not always to their credit.

A new archival find suggests that Japanese occupation was more devastating than previously thought

Population loss in Portuguese Timor during WW2 revisited

To take the US as an illustration, training was provided at a secret CIA base on the Pacific island of Saipan, which had as its cover name the “Naval Technical Training Unit”. This facility conducted courses in intelligence tradecraft, communications, counter-intelligence and psychological warfare. Burmese officers also attended CIA training courses on Okinawa, most likely at the Army Liaison School, later renamed the US Army Pacific Intelligence School. Classes focused on combat intelligence and intelligence collection. Tatmadaw officers may have also received “covert training” on Guam, provided by the Defence Intelligence Agency.

These and other such contacts must be taken into account when considering claims that the Kempeitai was the ideological wellspring of, if not the practical model for, Myanmar’s dreaded military intelligence apparatus. At the very least, the wide diversity of policy approaches, methodology and experiences to which Burmese intelligence officers were exposed during this early period must raise questions about their personal and professional development, and thus the sources of the Tatmadaw’s intelligence traditions, tactics and techniques.

The post Myanmar’s MI and the Kempeitai: a historical footnote appeared first on New Mandala.

This post was originally published on New Mandala.

Read RFA coverage of this topic in Burmese.

Myanmar’s ruling military battled to defend a major northern town on Wednesday as its forces also came under pressure in the west and the east and its most important ally China worked to stop the onslaught by insurgents determined to end the generals’ rule.

Forces of the junta that seized power in a February 2021 coup have been pushed back in different places across the country by ethnic minority insurgents and allied pro-democracy militias over the past year.

Ethnic Kachin insurgents have been attacking the northern city of Bhamo on the Irrawaddy River for two weeks and have advanced towards the military’s headquarters there.

Junta forces have responded with heavy airstrikes, residents said.

“Last night at around 8 p.m., the planes were dropping bombs. There must have been about 100 strikes,” said one Bhamo resident, who declined to be identified in fear of reprisals.

“On the side of the headquarters, fighting is continuing and we hear gunfire. We can also see houses near there burning.”

An aid organization in the area said 30 civilians had been killed and nearly 150 wounded in Bhamo since Dec. 4. Among the dead were 10 children and five nuns, said a spokesperson from the group who declined to be identified.

“It’s an approximation from people on the ground and those who fled,” said the spokesperson. “The dead were killed by airstrikes and heavy weapons, and some by shooting when they fled.”

RFA tried to telephone Kachin state’s junta spokesperson, Moe Min Thein, to ask about the situation in Bhamo but he did not answer.

China, the junta’s main foreign ally, has been trying to end the violence in its neighbour, where it has extensive economic interests including rare earth mines in Kachin state energy pipelines from the Indian Ocean, and has been pressing insurgents to strike ceasefires with the junta.

The chairman of the Kachin Independence Organization, or KIO, General N’Ban La, met senior Chinese official Wu Ken in the Chinese city of Kunming on Dec. 12 for talks on a truce with the Myanmar military and trade along Kachin state’s border with China, said Kachin military information officer Naw Bu.

“They discussed a ceasefire and opening gates along the border, then after fighting stops, they talked about having peace talks with the junta,” he said. “Neither side has made any formal decision or agreement.”

He declined to say if China was putting pressure on the KIA but China has in recent days pressed two insurgent groups in Shan state, to the southeast of Kachin state, to agree to ceasefires after cutting off border trade.

RELATED STORIES

Chinese aid cannot overcome Myanmar junta’s declining finances and morale

China undermines its interests by boosting support for Myanmar’s faltering junta

Sources: Junta representatives, leaders of rebel group in talks in China

Manerplaw re-captured

In Myanmar’s western-most Rakhine state, ethnic minority Arakan Army, or AA, insurgents have surrounded the army Western Command base in the town of Ann, one of the military’s last major headquarters in the state.

The AA released drone video footage of the base on Wednesday, showing burning buildings in ruins, with smoke rising. Radio Free Asia could not verify the date the video was taken but it was clearly of the Western Command headquarters.

The AA also released video of scores of captured men, hands tied, marching in a line with white flags of surrender.

In the east, Myanmar’s oldest insurgent group, the Karen National Union, or KNU, re-captured their headquarters at Manerplaw, which they lost in 1995 to the army following a split in their ranks.

“We are taking back the headquarters that we lost for 30 years,” said the group’s spokesman, Saw Taw Nee.

Manerplaw, on a river along the border with Thailand, is of great symbolic importance.

The Karen headquarters was the hub of opposition efforts by an alliance of ethnic minority groups and student fighters from the majority Burman community after the military crushed a pro-democracy uprising in 1988.

Those same groups are again striving for unity as they seek to end military rule and usher in what they say will be a democratic, federal Myanmar.

Translated by Kiana Dunan. Edited by RFA Staff.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by RFA Burmese.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Hong Kongers who go overseas are still winding up trapped in a notorious scam park operation in Myanmar, family members told RFA Cantonese in recent interviews after petitioning the city’s leader John Lee for help.

They are joining thousands of captives who are being held at a large compound in Kayin state called KK Park, a Chinese development project that has become a notorious center for scam operations.

Thousands of human trafficking victims from all over Asia — and as far away as Africa — are being held hostage there despite some attempts at rescue by the authorities. Former victims have said they were lured in by false advertisements and forced to scam other people, then tortured if they refused to comply.

A woman who gave only the nickname Mary for fear of reprisals, who was among three people to petition Chief Executive John Lee for assistance with disappeared family members on Tuesday, said she had lost contact with her son after he traveled to Thailand at the beginning of December “for work.”

He didn’t tell his family what kind of work he had planned, and remained in touch until the point where he is believed to have entered KK Park.

Asked if she fears for her son’s life, Mary told reporters: “That’s the thing I’m most worried about.”

Mary’s son is among at least 23 Hong Kongers believed to be lured into Southeast Asian scam operations this year, Secretary for Security Chris Tang told the Legislative Council on Dec. 3. Of those, 11 have returned to Hong Kong, Tang said.

While Tang told lawmakers that some people inside KK Park were “in contact” with loved ones, and that anyone working there had “entered voluntarily,” relatives of the missing say they haven’t heard from their loved ones at all, and that they were tricked into going there while traveling to completely unrelated countries like Japan and Taiwan.

RELATED STORIES

‘Thousands’ of trafficked people held at scam casino site amid escalating violence

Plea for help from telephone scam victims falls on deaf ears among Chinese officials

61 Vietnamese rescued from Myanmar casinos

Scam centers have plagued the border areas of Thailand, Myanmar and China as nationals from all three countries are tricked into — and subsequently enslaved in — online fraud.

The businesses typically force trafficked workers to call people across Asia and convince them to deposit money in fake or fraudulent investments.

Tens of thousands involved in the criminal schemes were deported from Myanmar in 2023 by both junta and rebel army officials. Many are linked to forced labor, human trafficking and money laundering, which proliferated after COVID-19 shut down casinos across Southeast Asia.

Six new cases

Former Yau-Tsim-Mong District Council chairman Andy Yu, who has previously helped Hong Kong families with loved ones in KK Park, said he has received six new cases of family members trapped at the site in recent weeks.

“There are a lot of family members who are unable to contact their loved ones, so they are wondering why the secretary for security said that they are in contact with those trapped there,” Yu told RFA Cantonese while delivering the petition on Tuesday.

Yu said the organization that runs the park now appears to be stopping them from contacting loved ones to let them know they’re OK, after previously allowing it.

“It’s been hard for family members to reach their loved ones lately, so they don’t even know if they’re OK or not,” he said.

Another family member of a person trapped in KK Park who gave only the nickname Calvin for fear of reprisals said his relative had been lured to Myanmar after traveling to Japan in search of a job as a purchasing agent six months ago.

They were only supposed to be gone for two or three days, so by day four, Calvin reported them missing to the Hong Kong police.

He later heard from his relative that they were being held in KK Park, but he hasn’t heard anything back from the police, he told RFA Cantonese.

Promises of jobs

Yu said victims are being lured initially to Japan and Taiwan, often with the promise of a job, then taken to Thailand, then to KK Park in Myawaddy.

Ransoms have skyrocketed in recent years, he said.

“Two years ago, you could have gotten out by paying a ransom of HK$500,000-600,000 (US$64,300-77,200),” Yu said. “Now, it’s much higher, more than HK$1 million (US$129,000), and that’s if they even offer a ransom.”

“Getting out of there isn’t easy,” he said.

While staff at his office accepted the families’ petition, Chief Executive John Lee made no mention of the issue when he took questions from reporters at a regular news briefing later in the day.

A United Nations report in August 2023 said that hundreds of thousands of people have been forced by organized criminal gangs into working at illegal casinos and other online scam work in Southeast Asia.