Look, I am around a lot of people, and I observe as well as talk and probe. Over time, say, since I was starting as a beat reporter at age 18, oh, in 1974, I have learned the collective trauma of victims outside the USA — Vietnam, Cambodia, Mexico, Guatemala, Nicaragua, Belize, El Salvador, Costa Rica, Honduras. And inside this place, all the domestic trauma, including on several reservations where I called aunts and uncles of friends my aunties and uncles.

My mom was born in British Columbia, so I know personally that place’s extruded trauma on original peoples.

Over time, just as a city reporter, beat cop reporter, and then more probing assignments, I saw and absorbed the trauma this society — this country’s ugly history has been laid bare but covered up well — and just getting under the nails of Memory of Fire in Latin America lends pause to the entire project of the Newest Project on the Latest American Century.

In his book, Mirrors: Stories of Almost Everyone (Nation Books; May 25, 2009), Uruguayan author Eduardo Galeano tells a history of the world through 600 brief stories of human adversity, focusing on people often ignored by history. Several passages of the book were read. The guest interviewer was John Dinges. They also discussed Mr. Galeano’s 1971 book, Open Veins of Latin America: Five Centuries of the Pillage of a Continent, which Venezuelan president Hugo Chavez gave to President Obama during the Fifth Summit of the Americas in April 2009. They talked about Mr. Galeano’s life and career, including military regimes, book bans, and repression — Video.)

All the winds of hell unleashed by the Anglo Franco American Germanic forebearers, well, here we are, halfway done with 2023, and we have a society so bad, so broken, so distracted, so traumatized, so checked out, so vapid, so dumbdowned, so heartless, so disconnected, so xenophobic, so patriotic, so miseducated, so misled, so screwed up by the snake oil of our times, and so propagandized and polluted physically, intellectually and spiritually, that a psychological descriptor for traumatized individuals fits the entire society (minus a few million).

Alexithymia has been associated with various impairments, including difficulties in emotional processing, identifying facial expressions, and understanding and relating to the emotions of others. It is also considered a risk factor for psychopathologies such as affective disorders, self-injury, personality disorders, and eating disorders.

Individuals with alexithymia often experience challenges in their interpersonal relationships, exhibiting limited socioaffective skills, decreased empathy, and a tendency to avoid close social connections. (The paper, “Child Maltreatment and Alexithymia: A Meta-Analytic Review,” was authored by Julia Ditzer, Eileen Y. Wong, Rhea N. Modi, Maciej Behnke, James J. Gross, and Anat Talmon.)

I’ll run another couple of paragraphs describing this research, and, yes, it focuses on child maltreatment, but to be honest, maltreatment is beyond the family and close relatives. Maltreatment is in the K12 school/prison system. The school to prison pipeline is one avenue of the mistreatment. But then, the school to Ivy League is another trauma. School to MBA program. School to military pipeline.

It can be in the backgrounds of Blinken or Obama or Bush or Clinton or Trump or Biden, or for their children — maltreatment is the lies these men and their women have flooded our world with. The outright open killing and murdering of people we sanction, those we disturb because we do not like their governments, they are in a dulled and numbed emotional spectrum.

Young adults going to war, sure, complex PTSD, but what about the destruction of war on the target countries, and the collective hell each generation that follows a war-torn country, what do they face?

The victims are in trauma, and so are the victimizers’ citizens, the so-called electorate here which pays taxes for these killings are also in the trauma zone.

Emotional abuse and emotional neglect are found to be the strongest predictors of adult alexithymia. These types of maltreatment, which are often more implicit and harder to recognize than physical or sexual abuse, can hinder the development of secure attachment between caregivers and children. Parlay this to the collective, the society at large, you know, it takes a society-village to raise a child. Look at this village, man, just look at the horrors unleashed in this VILLAGE.

“Child maltreatment encompasses more than physical and sexual abuse; it also includes emotional abuse and neglect, which have profound and enduring consequences,” Ditzer told PsyPost. “Through my research, I found that difficulties identifying and expressing emotions are most likely in adults who experienced emotional abuse and neglect. This highlights the critical importance of how we communicate with children.”

“I hope that readers are inspired to be more mindful of the messages we convey to our children through our words and the way we say them, as emotional abuse and neglect prevention can make a significant difference in children’s emotional well-being long-term. Generally, I hope to bring more attention to the topic of child maltreatment and its consequences.”

Look, I was at a grand opening of a small wine tasting business in my small town yesterday. I met the woman opening it a year ago, and she told me her story — in foster youth, abused there big time, and then in an abusive relationship for 17 years, and she got her real estate license and she made some good moves and so she owns a duplex here which she rents and one in Tulum which she rents and she has this business.

So, a 68-ish woman and I got into it waiting for the doors to open. I was talking to someone who asked what I was doing and what I was working on. I told them my work with homeless folk, civilians and veterans alike.

This vacationing woman said she was a retired parole officer, and she point blank told me, “I have no sympathy for druggies. It was their choice. It is all their fault.”

Talk about a trauma drenched and giving woman. I told her that was absurd, that every female veteran I worked with had been sexually assaulted by their own men in boot camp or sometimes overseas on duty. That many had injuries from absurd 20 mile hikes with 100 pound rucksacks on. Torn ligaments, protruding discs, and bad hip joints from parachuting.

And she blithely said, “I guess it was time for me to retire. I have no empathy.”

Retire, man, on our dime, and how long did she serve (sic) as a parole or probation officer, and how long did she just despise those criminals?

Where do they get this attitude, and this is not an anomaly? Believe me, I have duked it out with people my entire late teens and through all of my adult life. This retrograde, this trauma flooded society, again, collectively, we can call it Stockholm Syndrome, relating and empathizing with your captor. Valorizing them. We do that daily.

But this is emotional stunting, emotional victimizing, and eventually, a blindness to our humanity. And here we are, in 2023:

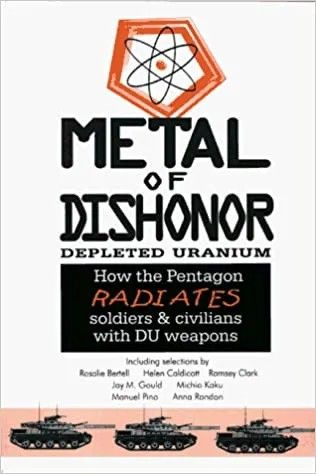

The United States will be sending depleted uranium munitions (DU) to Ukraine, reported The Wall Street Journal on June 13. This was written three months after Pentagon spokesperson Air Force Brig. Gen. Pat Ryder stated March 21 that to his knowledge the U.S. would not do so. (Los Angeles Times, March 21)

The announcement about sending DU munitions comes despite voluminous documentation about the devastating consequences of breathing in the radioactive dust caused by these weapons.

So, wherever I go, this emotional deadness, literally translated as “no words for emotions” is the major virus of the world now. And it keeps growing, attacking man, woman and child. Numb, dead, well, it is deeper than that. Our government and our corporations and our churches and religious leaders, all the marketers, all the armies of cops and code inspectors and fine levelers and repossession experts and tax men and eviction experts and on and on, they have killed our collective emotional souls whereupon this new Tokyo fire bombing is now Ukrainian DU bombing.

China has translated “Metal of Dishonor-Depleted Uranium,” a groundbreaking book compiled 25 years ago by the International Action Center (IAC) warning of the devastating consequences of deploying DU munitions. It couldn’t be more timely.

The preface to the Chinese edition warns:

Depleted uranium weapons are not only harmful to their targets, but also harmful to the soldiers who operate the weapons, civilians around depleted uranium — and even their descendants. It caused bodily harm and threatened the future natural environment [in countries where it was used].

At the same time, this book calls for the joint boycott and abolition of depleted uranium weapons and the realization of interactive exchanges and peaceful coexistence on a global scale.

There is so much disconnection to participatory and angry and direct action democracy that we have story after story telling us we can’t govern ourselves … until we are about to start a war in Venezuela, Cuba, China, and then into Russia. We are sick collectively:

He should be shot, of course, because he is a rabid rat. Beyond repair. A serial killer on the loose, but because of the deadened heart and brain of the collective Westerner, this guy just appears as yet another abuser, to be respected, regarded well and listened to: Individuals with alexithymia often experience challenges in their interpersonal relationships, exhibiting limited socioaffective skills, decreased empathy, and a tendency to avoid close social connections.

Hmm: why the world is criticizing the Biden administration for sending Ukraine these weapons:

“Years or even decades later, they can kill adults and children who stumble on them.”

Think about this, and you will understand how murdering Koreans in the 1950s was okay, then in Vietnam, then in Cambodia, then in Iraq, and then, well, name the country, and the USA has its hands on the killing machine and coup creating throttle. All that is okay, right? With Kissinger at 100 getting his next year of fame in interview after interview (sic — they are not real journalistic interviews, I have you know), how can a society collectively even move forward with a war criminal now giving sage advice?

This is 2023, and even children are not respected in this so-called Shining City on the Hill:

An aged Native-American chieftain was visiting New York City for the first time in 1906. He was curious about the city and the city was curious about him. A magazine reporter asked the chief what most surprised him in his travels around town.

“Little children working,” the visitor replied.

Child labor might have shocked that outsider, but it was all too commonplace then across urban, industrial America (and on farms where it had been customary for centuries). In more recent times, however, it’s become a far rarer sight. Law and custom, most of us assume, drove it to near extinction. And our reaction to seeing it reappear might resemble that chief’s — shock, disbelief.

But we better get used to it, since child labor is making a comeback with a vengeance. A striking number of lawmakers are undertaking concerted efforts to weaken or repeal statutes that have long prevented (or at least seriously inhibited) the possibility of exploiting children.

Take a breath and consider this: the number of kids at work in the U.S. increased by 37% between 2015 and 2022. During the last two years, 14 states have either introduced or enacted legislation rolling back regulations that governed the number of hours children can be employed, lowered the restrictions on dangerous work, and legalized subminimum wages for youths.

Iowa now allows those as young as 14 to work in industrial laundries. At age 16, they can take jobs in roofing, construction, excavation, and demolition and can operate power-driven machinery. Fourteen-year-olds can now even work night shifts and once they hit 15 can join assembly lines. All of this was, of course, prohibited not so long ago. (source)

Do you need to go back into Anglo Saxon history? Dickens anyone?

Do you need a lesson on capitalism and exploitation? Now, this history, this collective thinking and collective subconsciousness, this alternative way of being a human being, it is part of the abuse, from cradle to school to job to grave:

Hard work, moreover, had long been considered by those in the British upper classes who didn’t have to do so as a spiritual tonic that would rein in the unruly impulses of the lower orders. An Elizabethan law of 1575 provided public money to employ children as “a prophylactic against vagabonds and paupers.”

By the eighteenth century, the philosopher John Locke, then a celebrated champion of liberty, was arguing that three-year-olds should be included in the labor force. Daniel Defoe, author of Robinson Crusoe, was happy that “children after four or five years of age could every one earn their own bread.” Later, Jeremy Bentham, the father of utilitarianism, would opt for four, since otherwise, society would suffer the loss of “precious years in which nothing is done! Nothing for Industry! Nothing for improvement, moral or intellectual.”

American “founding father” Alexander Hamilton’s 1791 Report on Manufacturing noted that children “who would otherwise be idle” could instead become a source of cheap labor. And such claims that working at an early age warded off the social dangers of “idleness and degeneracy” remained a fixture of elite ideology well into the modern era. Indeed, it evidently remains so today.

When industrialization began in earnest during the first half of the nineteenth century, observers noted that work in the new factories (especially textile mills) was “better done by little girls of 6-12 years old.” By 1820, children accounted for 40% of the mill workers in three New England states. In that same year, children under 15 made up 23% of the manufacturing labor force and as much as 50% of the production of cotton textiles. (source)

Here we are, in constant upheaval, constant fight-flight-freeze-cower-forget-trauma-fear-hate-disappear. The emotions, that is, after two, four, six generations have disappeared on the normal human spectrum. No words for emotions, man.

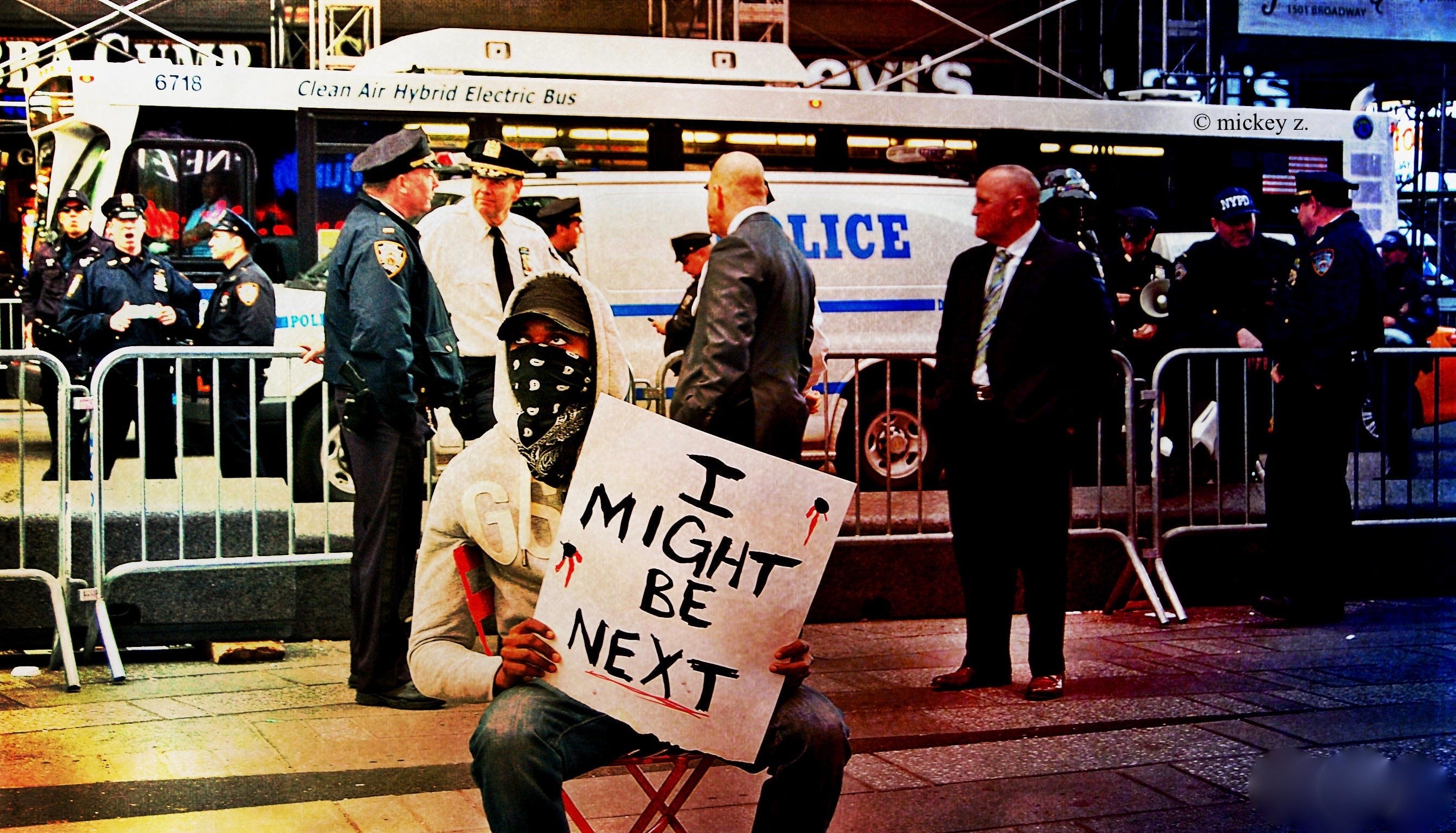

[Photo: This is what fascism and brown shirts look like.}

Zelensky returned home with five Azov commanders, who were initially taken prisoner by Moscow during a months-long battle to defend the port city of Mariupol.

Today it is still a challenge for the European Union and Spain in particular to carry out effectively the management of sub-Saharan migration, as promised. It is necessary that its humanitarian projection be comprehensive and safe.

A study published in the Informing Humanitarians Worldwide, deconstructs the vision of Africa as a continent of mass displacement and international migration.

The report explains that the largest migratory flow in Africa is between countries on the same continent. According to the International Agency for Migrations IOM, only 14 percent of the planet’s migrants were born in Africa. 53 percent of African migration is within the same continent, only 26 percent goes to Europe. Africa, then, is characterized more by being a continent of internal refugees than international migration.

The World Bank says nearly 80% (560 million) of the 700 million people who were pushed into extreme poverty in 2020 due to COVID policies were from India. Globally, extreme poverty levels increased by 9.3 per cent in 2020.

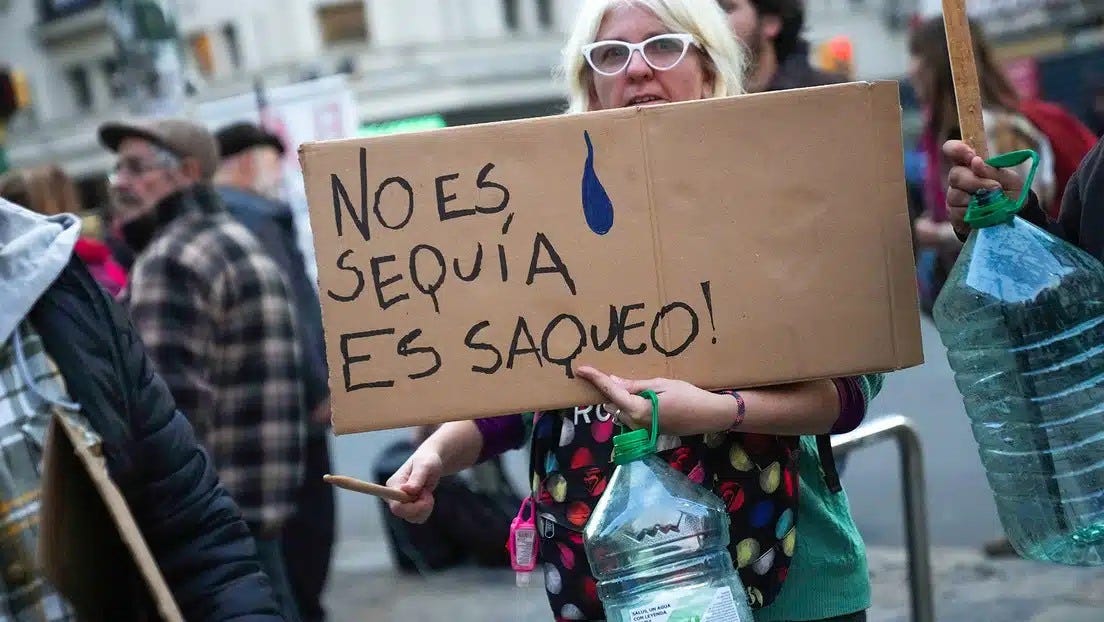

The lack of drinking water in Montevideo, “the first case in the world of a capital city that reached such a situation of collapse”. The daily dilemmas in the metropolitan area: what is said in the street and at the fair. The difference between the “water emergency” announced by President Lacalle Pou, and the ongoing environmental, sanitary and economic crisis. The impacts on people at risk, and on inequality among those who cannot afford the essentials. With fresh water reserves at 2%, with no drinking water at the taps, the chronicler says: “We crossed day zero without knowing it.”

“Coffee with water without salt, coffee with fresh water”, shouted the street vendor at the Tristán Narvaja fair on Sunday. (source)

It is so much, so much maltreatment, in the womb, then carried through the air, both the digital waves and air ways. It is the pain of the rich shitting on us, and after generations of this, we are seeing more and more people unable to conjure up what should be ire, disrepect, hate, disgust, denigration, murderous thoughts heaped upon those killers of the likes of a (F)uckerberg or Fink or any number of millions of millionaires and all the 3,000 billionaires. This is how these people beat the populations down:

While advocating for police abolition in his philanthropic efforts, Zuckerberg takes a different stance when it comes to his personal security.

Meta corporate disclosures show that the Facebook parent company has provided extraordinary levels of personal security protections for its leading officers. Zuckerberg received $13.4 million in personal security costs in 2020, then $15.1 million in 2021, followed by $14.8 million last year, for a total of $43.4 million in security costs over the last three years.

The funds, the disclosure noted, are used for “security personnel” guarding Zuckerberg and the “procurement, installation, and maintenance of certain security measures for his residences.”

So, his schizophrenia (it is about messing with the sheeple’s minds) just leaves most young people pummeled.

The tech tycoon’s company has spent more than $40 million on Zuckerberg’s personal security over the past three years — while at the same time his family-run foundation has donated millions of dollars to groups that want to defund or even abolish the police.

Since 2020, the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative (CZI) has donated $3 million to PolicyLink, the organization behind DefundPolice.org, according to investigative reporter Lee Fang.

The anti-cop group boasts on its website that it funds efforts to “diminish the role of policing in communities, and empower alternative visions for public safety,” though it fails to list what those substitutes may be.

CZI, which Zuckerberg founded with wife Priscilla Chan, has also donated more than $2.5 million to Solidaire, Fang reported, which seeks to do away with policing.(source)

If you recognize this in yourself, a friend, a loved one, then you get what is coming: affective disorders, nonsuicidal self-injury), personality disorders, and eating disorders. Moreover, the consequences of alexithymics’ emotional deficits extend beyond intrapersonal difficulties. Alexithymia interferes with individuals’ interpersonal relationships as they exhibit shortcomings in understanding and relating not only to their own emotions but also to the emotions of others. (source)

as if it were life support.

as if it were life support.

#NHS15Rise, Centralism is a myth! (@George0rw3ll)

#NHS15Rise, Centralism is a myth! (@George0rw3ll)

at the official opening of the 7th Melanesian Arts & Culture Festival (MACFEST).

at the official opening of the 7th Melanesian Arts & Culture Festival (MACFEST).

(@Haggis_UK)

(@Haggis_UK)

(@FredThomasUK)

(@FredThomasUK)