As President Biden and his Chinese counterpart Xi Jinping arrived on the resort island of Bali, Indonesia, for their November 14th “summit,” relations between their two countries were on a hair-raising downward spiral, with tensions over Taiwan nearing the boiling point. Diplomats hoped, at best, for a modest reduction in tensions, which, to the relief of many, did occur. No policy breakthroughs were expected, however, and none were achieved. In one vital area, though, there was at least a glimmer of hope: the planet’s two largest greenhouse-gas emitters agreed to resume their languishing negotiations on joint efforts to overcome the climate crisis.

These talks have been an on-again, off-again proposition since President Barack Obama initiated them before the Paris climate summit of December 2015, at which delegates were to vote on a landmark measure to prevent global temperatures from rising more than 1.5 degrees Celsius (the maximum amount scientists believe this planet can absorb without catastrophic consequences). The U.S.-Chinese consultations continued after the adoption of the Paris climate accord, but were suspended in 2017 by that climate-change-denying president Donald Trump. They were relaunched by President Biden in 2021, only to be suspended again by an angry Chinese leadership in retaliation for House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s August 2 visit to Taiwan, viewed in Beijing as a show of support for pro-independence forces on that island. But thanks to Biden’s intense lobbying in Bali, President Xi agreed to turn the interactive switch back on.

Behind that modest gesture there lies a far more momentous question: What if the two countries moved beyond simply talking and started working together to champion the radical lowering of global carbon emissions? What miracles might then be envisioned? To help find answers to that momentous question means revisiting the recent history of the U.S.-Chinese climate collaboration.

The Promise of Collaboration

In November 2014, based on extensive diplomatic groundwork, Presidents Obama and Xi met in Beijing and signed a statement pledging joint action to ensure the success of the forthcoming Paris summit. “The United States of America and the People’s Republic of China have a critical role to play in combating global climate change,” they affirmed. “The seriousness of the challenge calls upon the two sides to work constructively together for the common good.”

Obama then ordered Secretary of State John Kerry to collaborate with Chinese officials in persuading other attendees at that summit — officially, the 21st Conference of the Parties of the U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change, or COP21 — to agree on a firm commitment to honor the 1.5-degree limit. That joint effort, many observers believe, was instrumental in persuading reluctant participants like India and Russia to sign the Paris climate agreement.

“With our historic joint announcement with China last year,” Obama declared at that summit’s concluding session, “we showed it was possible to bridge the old divides… that had stymied global progress for so long. That accomplishment encouraged dozens and dozens of other nations to set their own ambitious climate targets.”

Obama also pointed out that any significant global progress along that path was dependent on continued cooperation between the two countries. “No nation, not even one as powerful as ours, can solve this challenge alone.”

Trump and the Perils of Non-Cooperation

That era of cooperation didn’t last long. Donald Trump, an ardent fan of fossil fuels, made no secret of his aversion to the Paris climate accord. He signaled his intent to exit from the agreement soon after taking office. “It is time to put Youngstown, Ohio; Detroit, Michigan; and Pittsburgh, PA, along with many, many other locations within our great country, before Paris, France,” he said ominously in 2017 when announcing his decision.

With the U.S. absent from the scene, progress in implementing the Paris Agreement slowed to a crawl. Many countries that had been pressed by the U.S. and China to agree to ambitious emissions-reduction schedules began to opt out of those commitments in sync with Trump’s America. China, too, the greatest greenhouse gas emitter of this moment and the leading user of that dirtiest of fossil fuels, coal, felt far less pressure to honor its commitment, even on a rapidly heating planet.

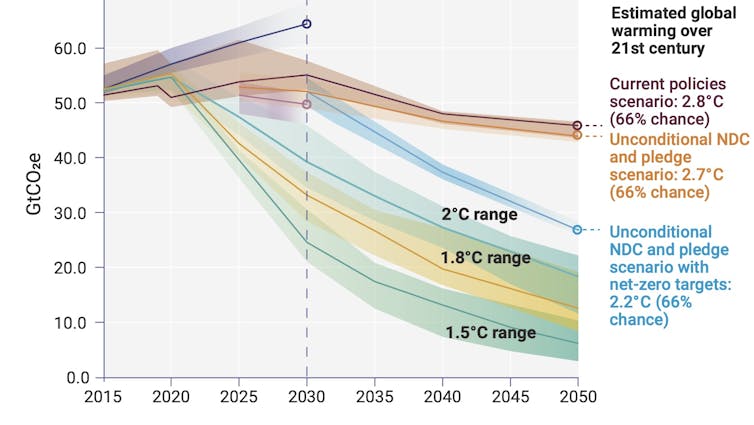

No one knows what would have happened had Trump not been elected and those U.S.-China talks not been suspended, but in the absence of such collaboration, there was a steady rise in carbon emissions and temperatures across the planet. According to CO.2.Earth, emissions grew from 35.5 billion metric tons in 2016 to 36.4 billion tons in 2021, a 2.5% increase. Since such emissions are the leading contributor to the greenhouse-gas effect responsible for global warming, it should be no surprise that the past seven years have also proven the hottest on record, with much of the world experiencing record-breaking heatwaves, forest fires, droughts, and crop failures. We can be fairly certain, moreover, that in the absence of renewed U.S.-China climate cooperation, such disasters will become ever more frequent and severe.

On Again, Off Again

Overcoming this fearsome trend was one of Joe Biden’s principal campaign promises and, against strong Republican opposition, he has indeed endeavored to undo at least some of the damage wrought by Trump. It was symbolic indeed that he rejoined the Paris climate accord on his first day in office and ordered his cabinet to accelerate the government’s transition to clean energy. In August, he achieved a significant breakthrough when Congress approved the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, which provides $369 billion in loans, grants, and tax credits for green-energy initiatives.

Biden also sought to reinvigorate Washington’s global-warming diplomacy and the stalled talks with China, naming John Kerry as his special envoy for climate action. Kerry, in turn, reestablished ties with his Chinese colleagues from his time as secretary of state. At last year’s COP26 gathering in Glasgow, Scotland, he persuaded them to join the U.S. in approving the “Glasgow Declaration,” a commitment to step up efforts to mitigate climate change.

However, in so many ways, Joe Biden and his foreign policy team are still caught up in the Cold War era and his administration has generally taken a far more antagonistic approach to China than Obama. Not surprisingly, then, the progress Kerry achieved with his Chinese counterparts at Glasgow largely evaporated as tensions over Taiwan only grew more heated. Biden was, for instance, the first president in memory to claim — four times — that U.S. military forces would defend that island in a crisis, were it to be attacked by China, essentially tossing aside Washington’s longstanding position of “strategic ambiguity” on the Taiwan question. In response, China’s leaders became ever more strident in claiming that the island belonged to them.

When Nancy Pelosi made that Taiwan visit in early August, the Chinese responded by firing ballistic missiles into the waters around the island and, in a fit of anger, terminated those bilateral climate-change talks. Now, thanks to Biden’s entreaties in Bali, the door seems again open for the two countries to collaborate on limiting global greenhouse gas emissions. At a moment of ever more devastating evidence of planetary heating, from a megadrought in the U.S. to “extreme heat” in China, the question is: What might any meaningful new collaborative effort involve?

Reasserting the Climate’s Centrality

In 2015, few of those in power doubted the overarching threat posed by climate change or the need to bring international diplomacy to bear to help overcome it. In Paris, Obama declared that “the growing threat of climate change could define the contours of this century more dramatically than any other.” What should give us hope, he continued, “is the fact that our nations share a sense of urgency about this challenge and a growing realization that it is within our power to do something about it.”

Since then, all too sadly, other challenges, including the growth of Cold War-style tensions with China, the Covid-19 pandemic, and Russia’s brutal invasion of Ukraine, have come to “define the contours” of this century. In 2022, even as the results of the overheating of the planet become ever more obvious, few world leaders would contend that “it is within our power” to overcome the climate peril. So, the first (and perhaps most valuable) outcome of any renewed U.S.-China climate cooperation might simply be to place climate change at the top of the world’s agenda again and provide evidence that the major powers, working together, can successfully tackle the issue.

Such an effort might, for instance, start with a Washington-Beijing “climate summit,” presided over by presidents Biden and Xi and attended by high-level delegations from around the world. American and Chinese scientists could offer the latest bad news on the likely future trajectory of global warming, while identifying real-world goals to significantly reduce fossil-fuel use. This might, in turn, lead to the formation of multilateral working groups, hosted by U.S. and Chinese agencies and institutions, to meet regularly and implement the most promising strategies for halting the onrushing disaster.

Following the example set by Obama and Xi at COP21 in Paris, Biden and Xi would agree to play a pivotal role in the next Conference of the Parties, COP28, scheduled for December 2023 in the United Arab Emirates. Following the inconclusive outcome of COP27, recently convened at Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt, strong leadership will be required to ensure something significantly better at COP28. Among the goals those two leaders would need to pursue, the top priority should be the full implementation of the 2015 Paris accord with its commitment to a 1.5-degree maximum temperature increase, followed by a far greater effort by the wealthy nations to assist developing countries suffering from its effects.

There’s no way, however, that China and the U.S. will be able to exert a significant international influence on climate efforts if both countries — the former the leading emitter of greenhouse gasses at this moment and the latter the historic leader — don’t take far greater initiatives to lower their carbon emissions and shift to renewable sources of energy. The Inflation Reduction Act will indeed allow the White House to advance many new initiatives in this direction, while China is moving more swiftly than any other country to install added supplies of wind and solar energy. Nevertheless, both countries continue to rely on fossil fuels for a substantial share of their energy — China, for instance, remains the greatest user of coal, burning more of it than the rest of the world combined — and so both will need to agree on even more aggressive moves to reduce their carbon emissions if they hope to persuade other nations to do the same.

The Sino-American Fund for Clean Energy Transitions

In a better world, next on my list of possible outcomes from a reinvigorated U.S.-Chinese relationship would be joint efforts to help finance the global transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy. Although the cost of deploying renewables, especially wind and solar energy, has fallen dramatically in recent years, it remains substantial even for wealthy countries. For many developing nations, it remains an unaffordable option. This emerged as a major issue at COP27 in Egypt, where representatives from the Global South complained that the wealthy countries largely responsible for the overheating of the planet weren’t doing faintly enough (or, in many cases, anything), despite prior promises, to help them shoulder the costs of the increasingly devastating effects of climate change and the future greening of their countries.

Many of these complaints revolved around the Green Climate Fund, established at COP16 in Cancún. The developed countries agreed to provide $100 billion annually to that fund by 2020 to help developing nations bear the costs of transitioning to renewable energy. Although that amount is now widely viewed as wildly insufficient for such a transition — “all of the evidence suggests that we need trillions, not billions,” observed Baysa Naran, a manager at the research center Climate Policy Initiative — the Fund has never even come close to hitting that $100 billion target, leaving many in the Global South bitter as, with unprecedented flooding and staggering heat waves, climate change strikes home ever more horrifically there.

When the U.S. and China were working on the climate together at COP26 in Glasgow, filling the Green Climate Fund appeared genuinely imaginable. In their Glasgow Declaration of November 2021, John Kerry and his Chinese counterpart, Xie Zhenhua, affirmed that “both countries recognize the importance of the commitment made by developed countries to the goal of mobilizing jointly $100b per year by 2020 and annually through 2025 to address the needs of developing countries [and] stress the importance of meeting that goal as soon as possible.”

Sadly enough, all too little came of that affirmation in the months that followed, as U.S.-China relations turned ever more antagonistic. Now, in the wake of Biden’s meeting with Xi and the resumption of their talks on climate change, it’s at least possible to imagine intensified bilateral efforts to advance that $100 billion objective — and even go far beyond it (though we can expect fierce resistance from the new Republican majority in the House of Representatives).

As my contribution to such thinking, let me suggest the formation of a Sino-American Fund for Green Energy Transitions — a grant- and loan-making institution jointly underwritten by the two countries with the primary purpose of financing renewable energy projects in the developing world. Decisions on such funding would be made by a board of directors, half from each country, with staff work performed by professionals drawn from around the world. The aim: to supplement the Green Climate Fund with additional hundreds of billions of dollars annually and so speed the global energy transition.

The Pathway to Peace and Survival

The leaders of the U.S. and China both recognize that global warming poses an extraordinary threat to the survival of their nations and that colossal efforts will be needed in the coming years to minimize the climate peril, while preparing for its most severe effects. “The climate crisis is the existential challenge of our time,” the Biden administration’s October 2022 National Security Strategy (NSS) states. “Without immediate global action to reduce emissions, scientists tell us we will soon exceed 1.5 degrees of warming, locking in further extreme heat and weather, rising sea levels, and catastrophic biodiversity loss.”

Despite that all-too-on-target assessment, the NSS portrays competition from China as an even greater threat to U.S. security — without citing any of the same sort of perilous outcomes — and proposes a massive mobilization of the nation’s economic, technological, and military resources to ensure American dominance of the Asia-Pacific region for decades to come. That strategy will, of course, require trillions of dollars in military expenditures, ensuring insufficient funding to tackle the climate crisis and exposing this country to an ever-increasing risk of war — possibly even a nuclear one — with China.

Given such dangers, perhaps the best outcome of renewed U.S.-China climate cooperation, or green diplomacy, might be increasing trust between the leaders of those two countries, allowing for a reduction in tensions and military expenditures. Indeed, such an approach constitutes the only practical strategy for saving us from the catastrophic consequences of both a U.S.-China conflict and unconstrained climate change.

This post was originally published on Latest – Truthout.

called for climate justice, self-determination & accountability

called for climate justice, self-determination & accountability talks of climate leadership but argues against binding human rights

talks of climate leadership but argues against binding human rights exposed polluters hiding behind the

exposed polluters hiding behind the

Just Released

Just Released