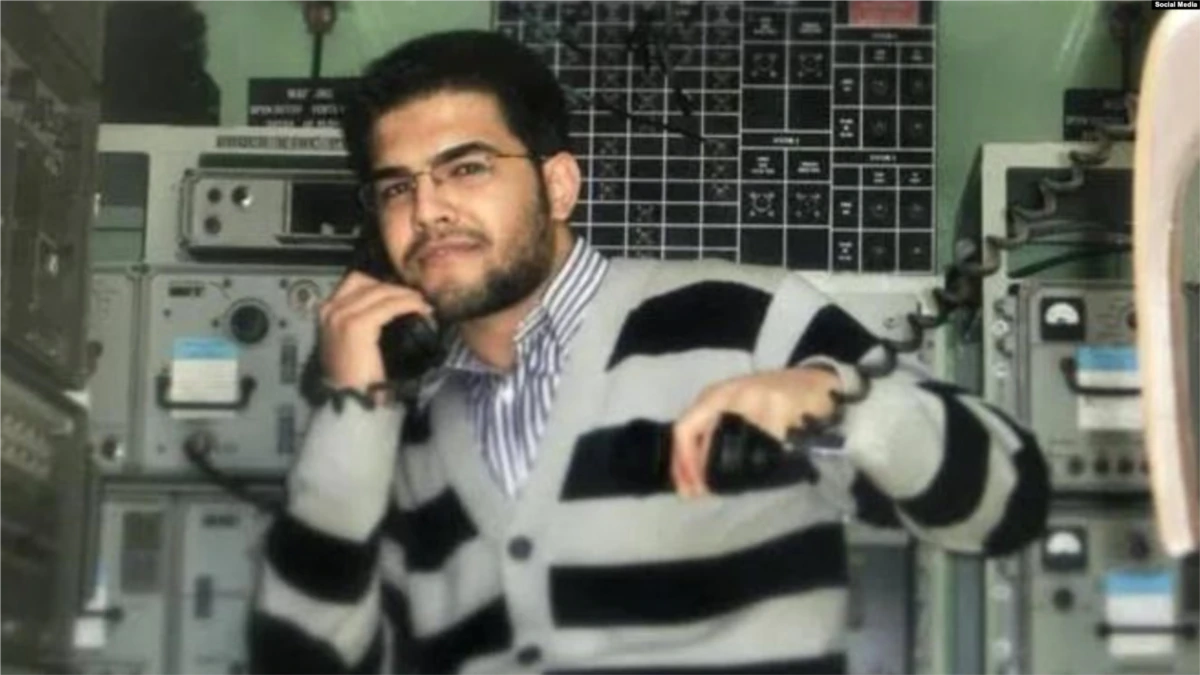

Kameel Ahmady spent years in Iran compiling research into the treatment of some of the most vulnerable elements of society.

His widely praised anthropological work shone a light on child marriage, sexual orientation, minorities and ethnicity, as well as official silence over the ongoing practice in Iran of female genital mutilation.

More recently, with a long prison sentence pending as one of the Iranian regime’s latest dual-nationals convicted on dubious charges of spying for the West, Ahmady made headlines with a daring escape on foot across Iran’s mountainous northeastern border.

But personal accounts by three Iranian women, whose identities are known to RFE/RL but who spoke on condition of anonymity out of fear for their safety, suggest that the Iranian-born and U.K.-educated Ahmady’s story may include a darker side — including sexual assault and other predatory behavior against women.

Two of those women accuse him of sexual assaults that date back several years and, in one case, possibly with the use of illegal drugs. The other says he once emerged from a bathroom naked and wanted her to fondle him.

When contacted by RFE/RL via e-mail, Ahmady demanded the names of the women who accused him in order to defend himself. He also agreed to be interviewed by Skype but later e-mailed to say he was seeking legal advice.

Ahmady has rejected allegations of sexual abuse in the past on multiple occasions.

In a February 12 statement to The Guardian, which published a story about sexual allegations against him the same day, he called the claims “deliberate slander and baseless, but also very well and deliberately organized, at both a state and personal level.”

Ahmady added that some people “used their gender” to “weaken my scholarly research and personal position” and to “create obstacles in my life…in their desire to gain power.”

Most of the public accusations that have previously emerged against Ahmady — and allegedly prompted his expulsion from a sociological association last year — have been anonymous.

RFE/RL knows the identities of the accusers and has maintained their confidentiality because they could face punitive action by Iran’s strict Islamic authorities for engaging in even nonconsensual sex if their assault charges were not believed once they told their stories.

The women also fear they could face shame and ostracism from families and friends over the episodes.

Researching The Vulnerable

As a researcher whose work has frequently focused on vulnerable members of society, Ahmady was in close contact with women who have suffered genital mutilation in their youth or are lesbian in a country that does not officially recognize homosexuality.

The allegations against Ahmady were first published on social media in late August as a worldwide #MeToo movement first gathered momentum in Iran.

It included an outpouring of reports of sexual abuse or rape from Iranian women who, in some cases, named their alleged abusers.

Eight women posted their accounts of alleged abuse on a feminist Twitter account called Bidarzani against a man who was identified by the initials “KA” or, in one case, as “Mr. X.”

RFE/RL learned through sources that Ahmady was the target of those accusations.

He then issued a statement on September 2 on social media saying that he “apologized” for some mistakes” at work and for “hurting” some people due to what he said was “my relaxed attitude and different views toward relationships.”

Detailed Accounts

At the time of the accusations on social media, Ahmady was awaiting sentencing after being charged with espionage, an offense that the Iranian judiciary often brings against dual nationals who have been used as bargaining chips in negotiations with the West.

In September, Ahmady was expelled from the Iranian Sociological Association, where he had been head of a group focusing on the sociology of childhood.

The association said its board of directors had “meticulously investigated” allegations of the sexual abuse of female colleagues by Ahmady and cited “available evidence” to expel Ahmady for “misusing one’s position of power” and “misusing relationships that were built on trust.” It concluded that “the behavior resulted in the sexual abuse of some younger [female] colleagues in the project.”

Since Almaty’s perilous escape to the West earlier this month, RFE/RL has spoken to three women who accused him of sexual misconduct after they met him through research projects on gender, child labor, or minority issues.

Two of the women offered detailed accounts of the assaults allegedly committed by Ahmady.

Another said he appeared naked in front of her after he invited her to his apartment and attempted to convince her to look at and touch his genitals. She said Ahmady attempted to manipulate and pressure her into having sex with him during the three years they worked together.

All three of the women cited the sensitivity of such issues in Iranian society, where women are often blamed for being sexually harassed or even raped.

Proving a crime like rape is extremely difficult and victims can face punishment based on laws that criminalize sexual relations outside of marriage.

Similar Stories

Marzieh Mohebi, a lawyer based in the northeastern city of Mashhad, told RFE/RL that she had been approached by four women who accused Ahmady of sexually assaulting them.

She said she believed the women’s claims but that they had insufficient evidence after the years since the assaults took place to prove their cases in an Iranian court.

“Those we talked to had his text messages, the text of their chats on Whatsapp and Telegram where he had invited them or threatened them, but it wasn’t solid enough for [an Iranian] court,” Mohebi said.

Activists have long complained of the difficulty of proving rape allegations in Tehran’s judicial system, which routinely discounts women’s testimony without concurring testimony from a man.

If unproven, such accusations can turn into prosecutions of female accusers of sexual wrongdoing under strict Islamic codes on marriage out of wedlock.

Mohebi said that, while the women did not know each other, their accounts were all similar.

“He would find his victims among girls and women active socially and would meet them for research purposes,” she said.

One of the women RFE/RL interviewed, a well-known researcher, said she was sexually assaulted by Ahmady during a field trip to an Iranian province about 10 years ago.

Another, an LGBT activist, said she was sexually assaulted by Ahmady in 2016.

All three women who spoke to RFE/RL were in their 20s when the alleged attacks took place.

They offered similar accounts of Ahmady inviting them to an apartment where he was staying in Tehran or other cities. They said he offered them alcohol and, in one case, a woman accused Ahmady of putting hashish in a water pipe without her knowledge. She said she became dizzy and felt she was losing consciousness before going to lie down. She said Ahmady entered the room and sexually assaulted her despite her protests.

A few days later and amid mounting anger, she told RFE/RL that she confronted him.

The other woman alleged that when Ahmady assaulted her she didn’t fight him as she was afraid he would harm her.

“I didn’t physically resist,” she said. “He looked very drunk and I was thinking that if he injures me, how am I going to explain it to my parents?”

#MeToo Arrives In Iran

She became the first woman to post an account of alleged sexual assault by Ahmady on Bidarzani amid last year’s social media campaign among Iranians highlighting sexual abuse.

She told RFE/RL that Ahmady later contacted her, asking her to remove the post and threatening to report her LGBT activism to Iranian authorities if she did not.

Meanwhile, her account of the alleged assault seems to have prompted several other Ahmady accusers to come forward.

A former colleague of Ahmady’s who now lives in Europe told RFE/RL that she had witnessed what she described as inappropriate and “unprofessional” behavior and language by Ahmady over the years. She said she had not witnessed any assaults.

The ex-colleague, who also did not want to be named, said Ahmady often talked about sex with women who seemingly trusted him due to their work relationship.

“He would pose as a hero who has come to save [Iranian] women from sexual deprivation,” she said. “I witnessed it many times.”

All of the women interviewed by RFE/RL, including the alleged victims, said they had been frustrated by the recent media reports depicting Ahmady as heroic because of his escape from Iran.

Ahmady authored a widely cited study on female genital mutilation five years ago that aimed to shatter official silence over the fact that the practice was being carried out on a large scale in some Iranian provinces.

Ahmady reportedly grew up in a largely ethnic Kurdish and Turkish town near the northwestern border where Turkey, Iraq, and Azerbaijan converge.

He emigrated in his late teens to the United Kingdom, where he studied anthropology at the University of Kent before returning to Iran in 2010, reportedly to look after his aging father.

State Harassment

Ahmady’s projects since then have focused on some of Iran’s most acute social and cultural fractures, including child marriage (which can be as young as 9 for girls, with court and parental permission), sexual orientation, ethnicity, and a groundbreaking study exposing officials’ failure to halt genital mutilation in women.

Iran’s hard-line clerical leadership frequently dismisses international pressure for tolerance on those issues and other matters — including the discriminatory treatment of women and a liberal application of the death penalty — as Western meddling.

Ahmady had previously complained of alleged harassment by Iran’s powerful Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps that he said targeted him over his research and its dissemination among other academics and lawmakers.

Born into Iran’s minority Kurdish community, Ahmady was sentenced in December to at least eight years in prison for allegedly collaborating with a hostile government — a charge he denies — and ordered to pay a fine equivalent to some $720,000.

He spent time in solitary confinement in Tehran’s notorious Evin prison and was released on bail before his recent escape in which he made his way through Iraq and Turkey to get to Europe.

“The sentence issued against him in Iran is unfair,” said the activist who claims Ahmady sexually assaulted her. “But at the same time the public should know who he is. I saw young students around him — these girls have a right to know.”

“The most important thing is for men like him who do these things to understand that they can’t get away with it,” another alleged victim told RFE/RL.

U.K.-based activist and doctoral student Zeinab Peyghambarzadeh said she had learned of accusations of sexual assault against Ahmady in 2017. Offenders, she said, should be held accountable in such cases.

“One shouldn’t face prosecution for doing research,” said Peyghambarzadeh, who last year signed a petition calling for Ahmady’s release from prison. “But a person who is facing [sexual assault] accusations should be investigated.”

Prominent Iranian-born women’s rights advocate Sussan Tahmasebi said Ahmady should be held accountable for any “unforgivable breach of trust with these most vulnerable communities and the harm that he has [allegedly] caused to social research in Iran.”

This post was originally published on Radio Free.