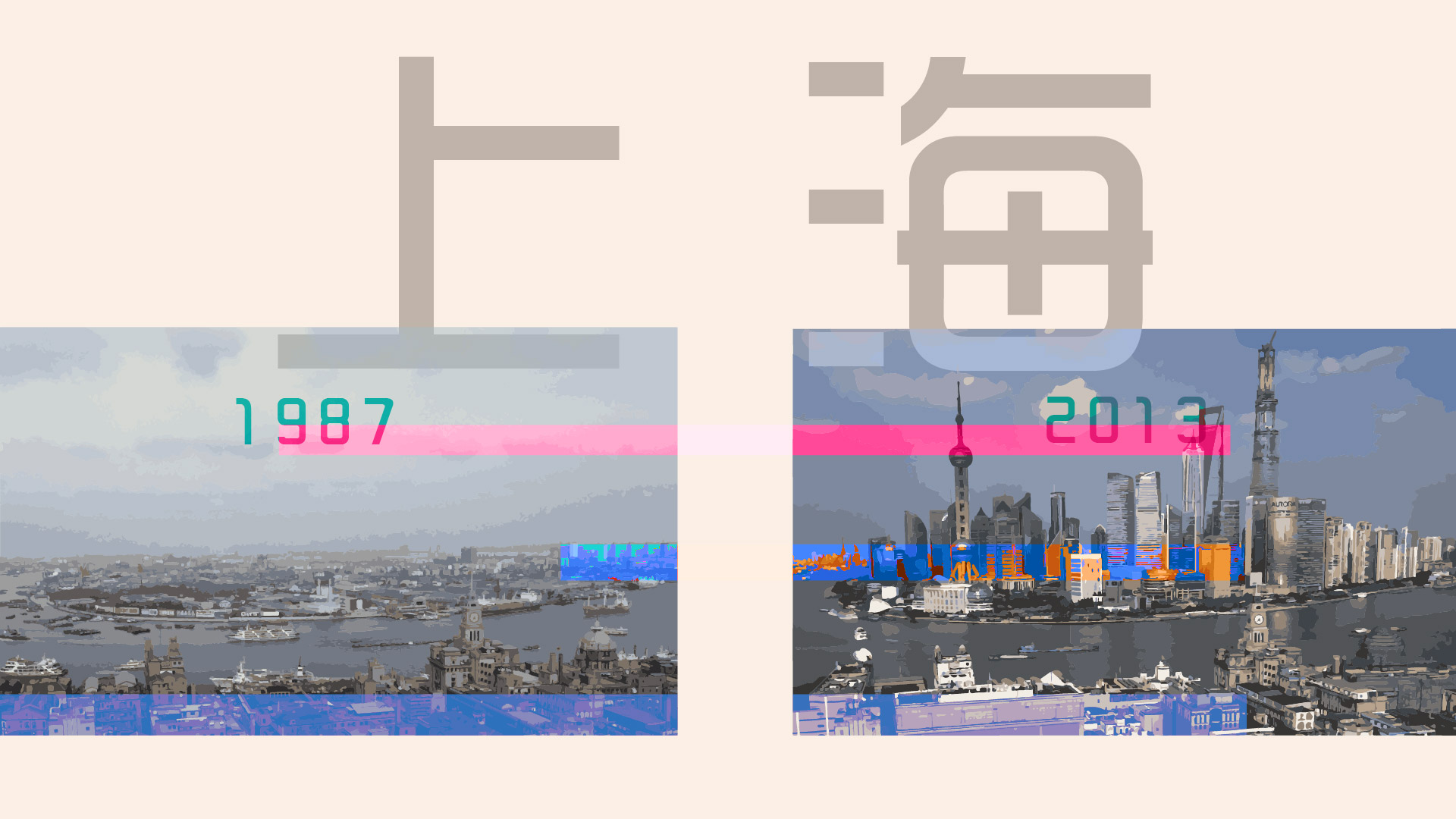

With over 20 million inhabitants each, Shanghai and Beijing are among the “hypercities” of the Global South, including Delhi, São Paulo, Dhaka, Cairo, and Mexico City, far surpassing the “megacities” of the Global North like London, Paris, or New York. Walking the streets in China’s cities, you will however, quickly notice one marked difference – the absence of large slums or pervasive homelessness that is so common to most of the rest of the world.

Slums were not uncommon in Chinese cities a few decades ago, from the precarious working class districts of 1930s Shanghai to the shanty towns of British-occupied Hong Kong in the 1950s onwards. How did China manage to develop in a way that decreased mass housing precarity? What are the structural reasons behind it?

This issue of Dongsheng Explains looks into how the Chinese government deals with homelessness, how this issue relates to socialist construction, and how China confronts the challenges posed by rapid economic development, urbanization, and the migration of recent decades.

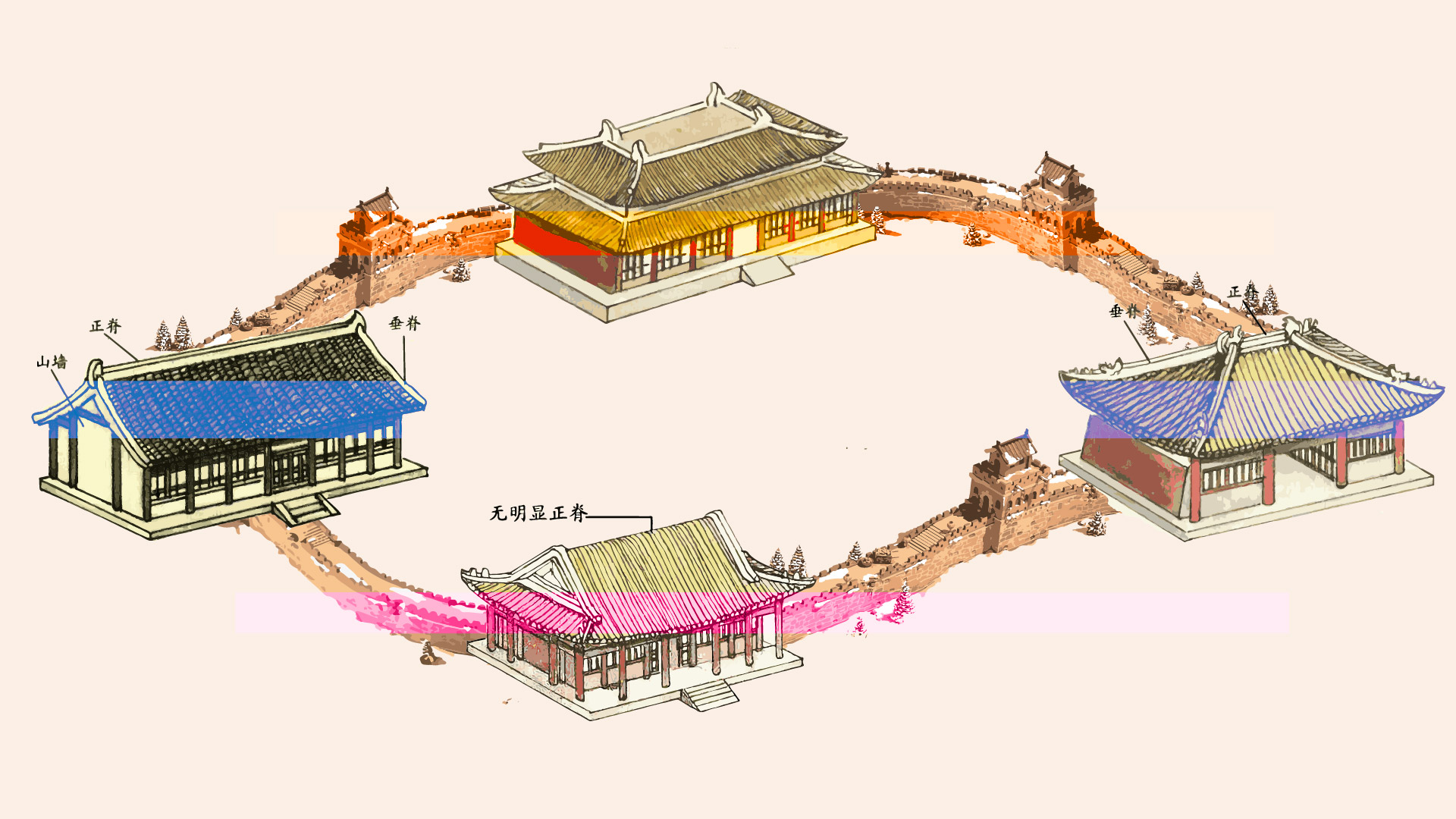

Why did mass urbanization not create large slums in China?

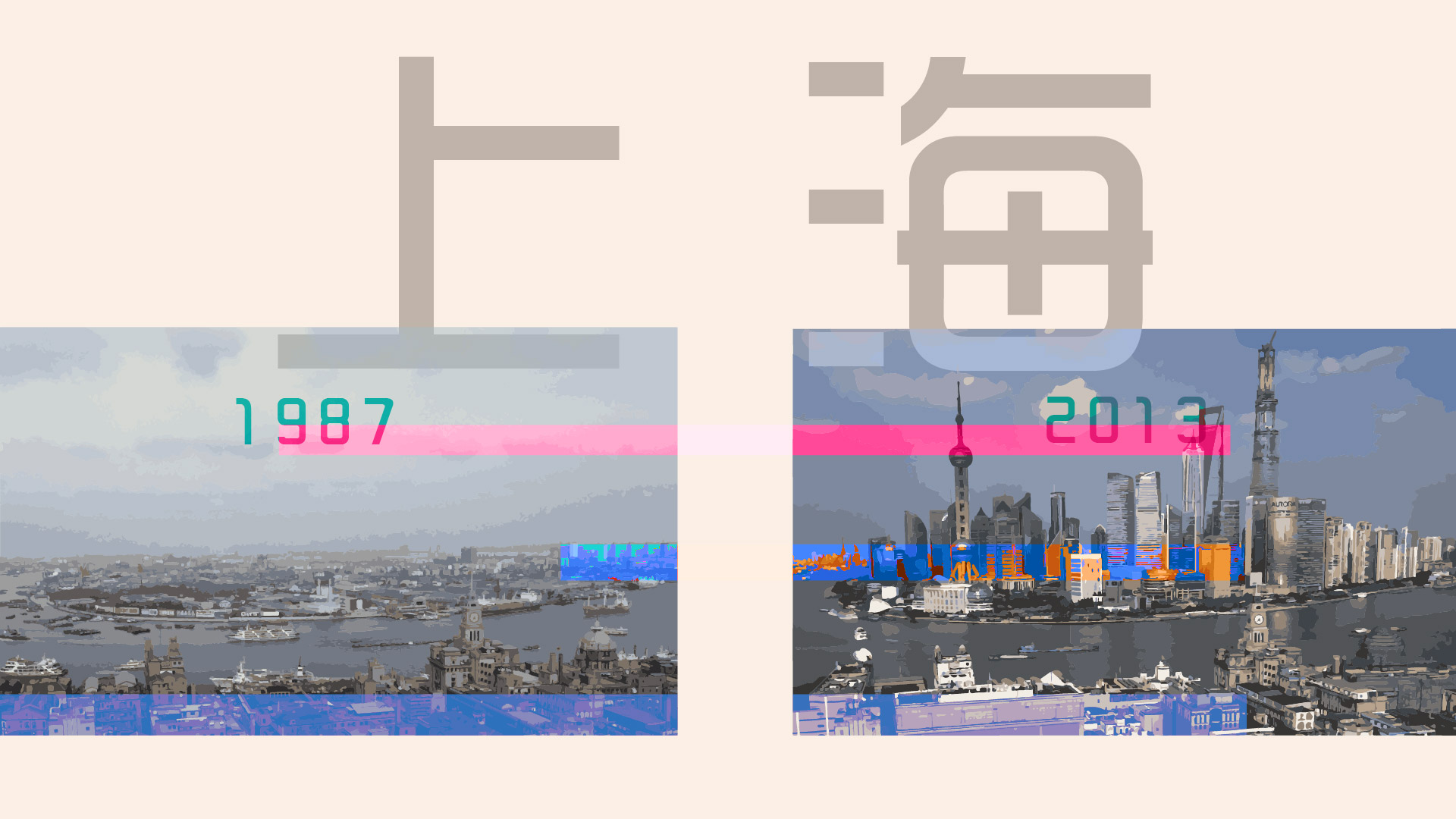

When reform and opening up began in the late 1970s, 83 percent of China’s population lived in the countryside. By 2021, the proportion of the rural population had fallen to 36 percent. During this period of mass urbanization, over 600 million people migrated from rural areas to cities.

Today, there are 296 million internal “migrant workers” (农民工, nóngmín gōng), comprising over 70 percent of the country’s total workforce. Migrant workers became the economic engine of China’s rapid growth, which created the world’s largest middle class of 400 million people.

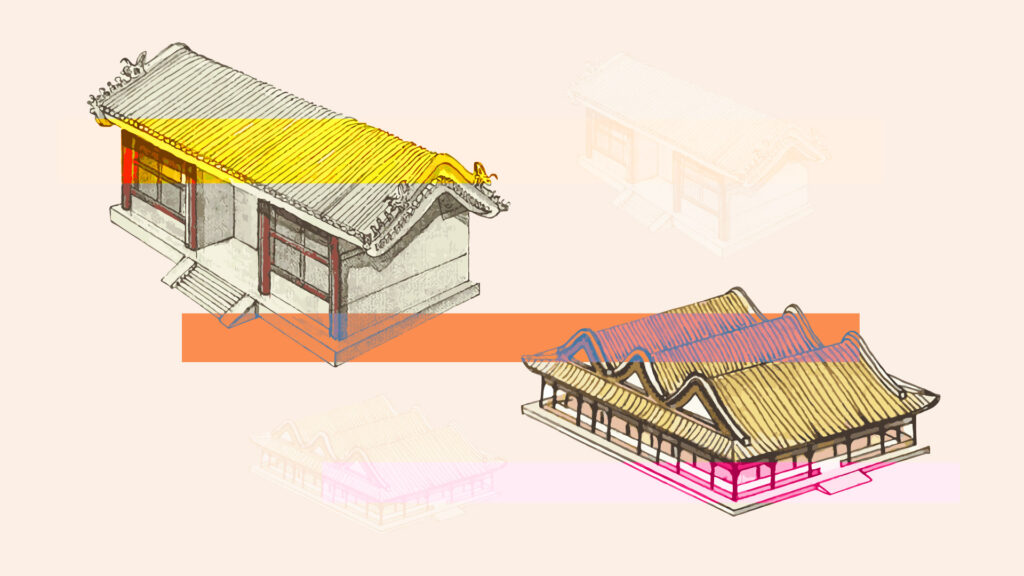

This historic migration came with many challenges, including the emergence of “urban villages” that had poor living conditions and inadequate infrastructure. Although basic amenities – such as running water, electricity, gas, and communications – were provided, sanitation, public services, fire safety, and other such amenities resembled that of rural villages. Due to lower rents and the lack of other affordable housing, urban villages are largely inhabited by migrant workers.

With the acceleration of urbanization in the 2000s, the Chinese government began to promote large-scale transformation of the old areas of the cities, focusing on renovation of historically deteriorated neighborhoods and the removal of dangerous housing. Between 2008 and 2012, 12.6 million households in urban villages were rebuilt nationwide.Migrant workers are workers whose household registration is still in rural areas and who are engaged in non-agricultural industries or leave their hometowns for work in another part of the country for at least six months of the year. At the same time, efforts were made to construct public rental or low-rent housing. For instance, in Shanghai today, families of three or more people with a monthly income of less than 4,200 yuan per person can apply for low-rent housing, with the monthly rent being just a few hundred yuan (or five percent of monthly household income). In 2022, the central government announced the construction of 6.5 million units of low-cost rental housing in 40 cities, representing 26 percent of the total new housing supply in the 14th Five-Year Plan (2021-2025).

Indeed the explosion of rural-to-urban migration in recent decades is not a phenomenon unique to China. While understanding that there are different definitions of “slums” used by countries and international organizations, they all point to the same tendency: since the 1970s, slum growth outpaced urbanization rates across the Global South. China’s efforts to upgrade existing precarious housing or build new affordable housing does not, however, explain why China did not develop slums like in so many other countries. Urbanization in China, therefore, must be understood within the context of socialist construction.

What is the “hukou” system and what does it have to do with socialism?

One unique characteristic of China’s urbanization process is that, although policies encouraged migration to cities for industrial and service jobs, rural residents never lost their access to land in the countryside. In the 1950s, the Communist Party of China (CPC) led a nationwide land reform process, abolishing private land ownership and transforming it into collective ownership. During the economic reform period, beginning in 1978, a “Household Responsibility System” (家庭联产承包责任制 jiātíng lián chǎn chéngbāo zérèn zhì) was created, which reallocated rural agricultural land into the hands of individual households. Though agricultural production was deeply impacted, collective land ownership remained and land was never privatized.

Today, China has one of the highest homeownership rates in the world, surpassing 90 percent, and this includes the millions of migrant workers who rent homes in other cities. This means that when encountering economic troubles, such as unemployment, urban migrant workers can return to their hometowns, where they own a home, can engage in agricultural production, and search for work locally. This structural buffer plays a critical role in absorbing the impacts of major economic and social crises. For example, during the 2008 global financial crisis, China’s export-oriented economy, especially of manufactured goods, was severely hit, causing about 30 million migrant workers to lose their jobs. Similarly, during the Covid-19 pandemic, when service and manufacturing jobs were seriously impacted, many migrant workers returned to their homes and land in the countryside.

Beyond land reform, a system was created to manage the mass migration of people from the countryside to the cities, to ensure that the movement of people aligned with the national planning needs of such a populous country. Though China has had some form of migration restriction for over 2,000 years, in the late 1950s, the country established a new “household registration system” (户口 or hùkǒu) to regulate rural-to-urban migration. Every Chinese person has an assigned urban or rural hukou status that grants them access to social welfare benefits (subsidized public housing, education, health care, pension, and unemployment insurance, etc.) in their hometown, but which are restricted in the cities they move to for work. While reformation of the hukou system is ongoing, the lack of urban hukou status forces many migrant parents to spend long periods away from their families and they must leave their children in their grandparents’ care in their hometowns, referred to as “left-behind children” (留守儿童 liúshǒu értóng). Though the number has been decreasing over the years, there are still an estimated seven million children in this situation. Today, 65.22 percent of China’s population lives in cities, but only 45.4 percent have urban hukou. Although this system deterred the creation of large urban slums, it also reinforced serious inequities of social welfare between urban and rural areas, and between residents within a city based on their hukou status.

How does the Chinese government deal with homelessness?

In the early 2000s, the issues of residential status, rights of migrant workers, and treatment of urban homeless people became a national matter. In 2003, the State Council – the highest executive organ of state power – issued the “Measures for the Rescue and Management of Itinerant and Homeless in Urban Areas.” The new regulation created urban relief stations providing food rations and temporary shelters, abolished the mandatory detention system of people without hukou status or housing, and placed the responsibility on the local authorities for finding housing for homeless people in their hometowns.

Under these measures, cities like Shanghai have set up relief stations for homeless people. When public security – the local police – and urban management officials encounter homeless people, they must assist them in accessing nearby relief stations. All costs are covered by the city’s fiscal budget. For example, the relief management station in Putuo District (with the fourth lowest per capita GDP of Shanghai’s 16 districts and a resident population of 1.24 million), provided shelter and relief to an average of 24.3 homeless people a month from June 2022 to April 2023, which could include repeated cases.

Relief stations provide homeless people with food and basic accommodations, help those who are seriously ill access healthcare, assist them to return to the locations of their household registration by contacting their relatives or the local government, and arrange free transportation home when needed.

Upon returning home, the local county-level government is responsible to help the homeless people, including contacting relatives for care and finding local employment. For a very small number of people who are elderly, have disabilities, or do not have relatives nor the ability to work, the local township people’s government, or the Party-run street office, will provide national support for them in accordance with the “method of providing for extremely impoverished persons”, which is stipulated in the 2014 “Interim Measures for Social Assistance”. The content of the support includes providing basic living conditions, giving care to impoverished individuals who cannot take care of themselves, providing treatment for diseases, and handling funeral affairs, etc.

This series of relief management measures ensure that administrative law enforcement personnel in the city do not simply expel homeless people from the city, but must guarantee that they receive proper assistance, in terms of housing, work, and support systems.

What are the current challenges of urbanization, migration, and inequality?

While creating relief centers is an important advancement, it is clear that shelters are not a structural solution and they alone cannot meet the needs of a metropolis like Shanghai of 25 million people, let alone the country’s 921 million urban residents. The government has been implementing many structural reforms to address inequality, and to make the cities and the countryside more liveable.

In his report to the 20th National Congress of the CPC, President Xi Jinping said: “We have identified the principal contradiction facing Chinese society as that between unbalanced and inadequate development and the people’s ever-growing needs for a better life, and we have made it clear that closing this gap should be the focus of all our initiatives.” The unbalanced and inadequate development points to the gap between the countryside and cities, between underdeveloped and industrialized regions, and between the rich and poor.

On a broader scale, the anti-poverty campaigns – highlighted by the eradication of extreme poverty in 2020 – and the rural revitalization strategy have helped alleviate the pressure of migrant workers moving to the cities. The government has invested substantial funds and resources, using diversified ways to alleviate poverty beyond income-transfer schemes, including developing rural industry, education, health care, and infrastructure. These measures fundamentally improved the living and employment environment in rural areas and created more opportunities so that people have the option to stay and work in the countryside. For example, every year, more migrants are returning from cities back to their hometowns, which increased from 2.4 million (2015) to 8.5 million people (2019).

Over the last decade, China has implemented reforms to balance the easing of hukou residency requirements and to improve the social welfare of migrant workers, while ensuring that urbanization and population distribution responds to the country’s needs. Since 2010, major cities have gradually relaxed the household registration restrictions for school admission, allowing children of migrant workers to attend public schools like children with local hukou. Furthermore, according to the 2019 Urbanization Plan, cities with populations below three million people are required to remove all hukou restrictions, while bigger cities (under five million) can begin to relax restrictions. The 14th Five-Year Plan (2021-2025) and the country’s economic strategy until 2035 focus on redistributing income through tax reform, reducing the gap between the rich and poor, and removing the barriers that prevent millions of migrant workers from enjoying the full benefits of urban life. In 2021, the government invested US$5.3 billion to relax the hukou residency rules, and to also boost urban migrants’ spending power as part of the country’s “dual circulation” policy.

These efforts to tackle the “three mountains” of the high cost of housing, education, and health care faced by all Chinese people, including migrants, is at the center of the government’s vision and policy reforms towards “common prosperity” for all its citizens and the building of a modern socialist society.

ENDNOTES

This content originally appeared on Dissident Voice and was authored by Dongsheng News.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Join a Union (@BenClaimant)

Join a Union (@BenClaimant)

(@mrkernow)

(@mrkernow)