Now is a time of unprecedented opportunity for progressive change. The reason is simple: “the system” is ruining the future for young people. Any system that threatens the future of its young people cannot retain their support and therefore is ripe for basic change.

Every morning, the daily news provides fresh evidence that “the system” is heading off a cliff—fruitless climate talks; growing nuclear threats; microplastics in food, water, breast milk and newborn babies; oceans damaged by warming, acidification, and dead zones; the military-industrial dragon preparing for war with China; Congress out of touch and deadlocked….

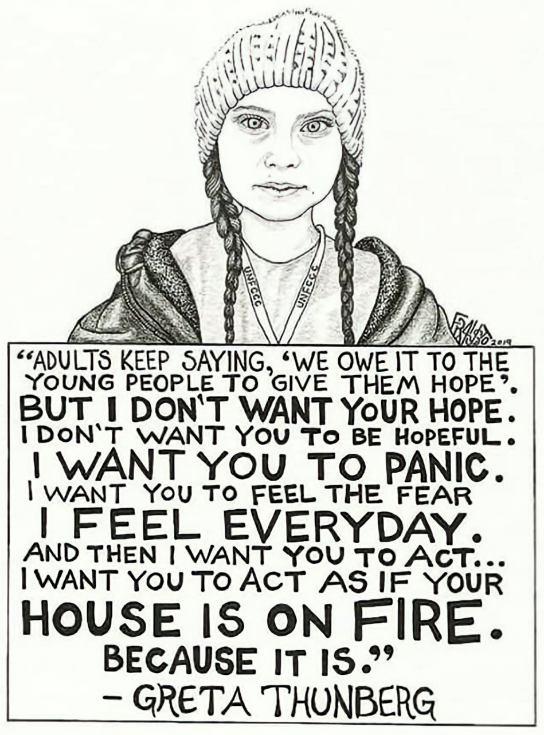

But there’s also good news: every day more young people are waking up to the facts and demanding that the system change.

What do I mean by “the system”? Back in 1996, when he was the editor of Harper’s magazine, Lewis Lapham described it as “the permanent government.”

Only slightly tongue-in-cheek, Lapham wrote, “The permanent government, a secular oligarchy… comprises the Fortune 500 companies and their attendant lobbyists, the big media and entertainment syndicates, the civil and military services, the larger research universities and law firms. It is this government that hires the country’s politicians and sets the terms and conditions under which the country’s citizens can exercise their right—God-given but increasingly expensive—to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Obedient to the rule of men, not laws, the permanent government oversees the production of wealth, builds cities, manufactures goods, raises capital, fixes prices, shapes the landscape, and reserves the right to assume debt, poison rivers, cheat the customers, receive the gifts of federal subsidy, and speak to the American people in the language of low motive and base emotion.”

The permanent government is ruining the future for young people in two ways:

(1) destroying the natural world that humans depend upon for life itself—air, water, soil, vegetation, and wildlife, and

(2) degrading the social/economic sphere, creating a vast chasm between the megarich and everyone else, inciting anger and resentment that divide us against ourselves, which prevents us from protecting the natural world that sustains us.

Resentment is rising as social conditions are deteriorating

Radio host Thom Hartmann recently compared economic conditions for two groups of people of equal size in the U.S.: Baby Boomers (average age 67 today) versus Millennials (average age 33 today).

Back when the average Boomer was 33, Boomers held 21.3 percent of the nation’s wealth; in contrast, Millennials age 33 today hold only 4.6 percent of the nation’s wealth. Prospects for Gen-Z are no better.

Hartmann identifies seven trends that have robbed young people of their fair share of prosperity: It boils down to the so-called “Reagan Revolution,” which Republicans (along with some Democrats) have pursued since 1980.

#1. Attack on wages

The attack on wages has three parts: (1) a coordinated offensive against labor unions, (2) passage of “right to work”(aka “right to work for less“) laws, and (3) flooding the political system with dark money so the megarich rule and ordinary people have no say.

Right-to-work-for-less laws prevent unions from collecting dues from workers who benefit from collective bargaining but who choose to withhold dues from the union that bargains on their behalf. This weakens unions, which reduces the incentive to join one, which weakens unions further.

Now 27 states have enacted such laws. Hartmann writes, “In every single case, anti-worker right-to-work laws have been passed in states controlled by Republicans at the time of passage.”

The attack on unions has succeeded. In 1983, 20 percent of workers were unionized; in 2021 it had dropped by half to 10.3 percent, even though 70 percent of Americans approve of unions.

As a result of these trends, today working people are taking home a 10% smaller share of the nation’s economic pie (“the labor share”) than they did in 1980. Ten percent may not sound huge, but it represents a transfer of 50 trillion dollars from working families to shareholders and business owners since 1975. Fifty trillion dollars. That’s $13,000 per year taken from every single worker in the bottom 90% of the wage-scale, year after year for 40 years.

Young people have been hit especially hard. In 1940, 90 percent of young people could expect to earn more than their parents. For children born in the 1980s, that measure of “absolute income mobility” has fallen to 50%—a major change that has degraded the future for tens of millions of young people.

No wonder working-class parents are angry and resentful as they see themselves precariously treading water, their children falling behind. This is where Trumpism began; then some cynical, privileged Republicans fanned those embers into flames. In 2018, Reuters/Ipsos asked 1,249 Trump voters what “Make American Great Again” meant to them and 2/3rds (63 percent) responded, “A better economy.”

#2. Restricting educational opportunity

Republican policies have put higher education out of reach for many children of low-income families and put millions more into crippling debt.

Professor Devin Fergus, now at the University of Missouri, has described the effects of the “Reagan revolution” on student debt. Prior to 1980, states paid 65% of student college costs, the federal government paid another 15%, leaving 20% for students to pay. Thom Hartmann has described how Mr. Reagan and his fellow “revolutionaries” set out to change all that. Students were “too liberal,”Mr. Reagan said, so “America should not subsidize intellectual curiosity.”After 40 years of defunding education, 44 million students are now saddled with $1.5 trillion in debt, making it hard or impossible for two generations of young people to create businesses, start families, or buy homes.

#3. Raising the price of a home

In 1950, the average price of a house was 2.2 times the median American family income. Today the median family income is $37,522 and the average house sells for ten times that amount—$374,900.

#4. “Financializing” the economy

As early as 2013, Bruce Bartlett, who served as an advisor to Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush, described how Wall Street firms have grown in proportion to the whole economy. In 1950 the financial services industry represented 2.8% of gross domestic product (GDP); in 1980 that proportion has grown to 4.9% and by 2013 it has reached 8.3 percent. In 1980, wages and salaries in financial services were comparable to other industries. But then compensation in financial services began to rise and, by 2013, people in financial services were taking home 70 percent more than their counterparts elsewhere in the economy. Thus, financialization of the economy “is a major cause of rising income inequality,” Bartlett says.

#5. Tolerating monopolies

Competition is supposed to be the life blood of our economic system. As the Hamilton Project explains it, “Competition is the basis of a market economy. It forces businesses to innovate to stay ahead of other firms, to keep prices as low as they can to attract customers, and to pay sufficient wages to avoid losing workers to other firms. When businesses vie for customers, prices fall and economic output increases. When businesses hire workers away from each other, wages rise and workers’ standard of living improves. And as unproductive firms are replaced by innovative firms, the economy becomes more efficient.”

President Reagan ordered an end to anti-trust enforcement in 1983 and consolidation (contrary to U.S. law) has now affected many parts of the economy—agriculture, banking, insurance, hospitals, pharmaceuticals, internet providers, cable companies, gigantic food corporations, grocers, home mortgages, office supplies. Result: prices spiral upward, wages decline, jobs disappear.

#6. Profiting from disease and disability

In 1960, U.S. health care costs were 5 percent of gross domestic product (GDP); by 2020, health care had risen to 19.7 percent of GDP. People in the U.S. don’t use more health care services than people in other countries; they just pay more for them.

According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, 9% of U.S. adults (23 million people) are carrying medical debt totaling $195 billion. According to Forbes magazine, in 2021, one-in-five households (19 percent) “could not pay for medical care when it was needed.”How do you think that made them feel?

#7. Handouts for the megarich

If Republicans agree on nothing else, they agree on cutting taxes for the super-rich so their vast accrued wealth can “trickle down”upon the rest of us and (as a side benefit) can starve government so it can’t regulate business or provide “socialist”amenities like schools, hospitals, and old-age insurance (social security).

As Thom Hartmann puts it, “Reagan dropped the top income tax on the morbidly rich from 74 percent down to 27 percent and cut corporate tax rates from 50 percent to functionally nothing… The average billionaire pays an income tax of under 3 percent and the majority of the nation’s largest corporations pay nothing.”

Recent studies show that in the 3-year period 2018-2020, 39 major corporations paid no taxes on $120 billion in profits and 73 others paid an average of only 5.3 percent during the period.

When billionaires and wealthy corporations don’t pay their fair share of taxes, the cost of running government gets dumped onto average citizens, who feel it, resent it, and then blame government for being weak and out of touch.

Summary

As things stand now, many working-class parents and their children are screwed, disrespected, even mocked as “deplorables.” Naturally they are seething with anger and resentment.

Cynical privileged Republicans have studied how to mobilize this resentment, to deflect it away from “the system”onto immigrants, gays, people Of Color, non-Christians and anyone who protests inequality or injustice (“slackers”and “hippies”). Yes, some privileged Republicans are more than just cynical; some are Nazis or Nazi sympathizers joined by dupes or dimwits or groupies—but most weren’t born that way; they have been bent by circumstance. Only 1 to 4 percent of people are born psychopaths without empathy or a conscience.

It is not fashionable to say so, but America is in trouble mostly because it no longer has a major political party sticking up for the working class. Since the mid-1970s, the permanent government has guided both major parties to benefit the few, not the many. Until that changes, we will have white-hot resentment and privileged opportunists who will trade on that resentment, creating rancor, division, and political stalemate, which will prevent us from protecting and repairing the natural world or spreading the wealth, upon which the future of all young people depends.

What is to be done?

In 2020, Nick Hanauer proposed a new kind of organization. Mr. Hanauer wrote, “…Imagine an AARP for all working Americans, relentlessly dedicated to both raising wages and reducing the cost of thriving—a mass membership organization so large and so powerful that our political leaders won’t dare to look the other way. Only then, by matching power with power, can we clear a path to enacting the laws and policies necessary to ensure that that trickle-down economics never threatens our health, safety, and welfare again.”

In 2018 the AARP had 38 million members.

Could Mr. Hanauer’s idea be built upon by young people, with support from their elders? Could we, together, create a new organization for all working Americans and for all young people, who are now losing their future? A mass-based organization dedicated to raising wages and to reducing the costs of thriving and to guaranteeing a future for young people by protecting and repairing the natural world. Large majorities of Americans already support these ideas.

Maybe name it simply: The Future.

Every existing issue-focused organization, including every labor union (like mine, the National Writer’s Union) could urge its members to not only support their own particular issues but also to join and help create The Future. Make membership dues affordable for everyone: No more than $10 per year. Recruit like crazy, build, deliver results.

Youth are already getting organized to protect their future. With youth choosing the path and leading the way, we elders could join The Future to serve as volunteer benefactors, fundraisers, cheer leaders, publicists, social-media posters, recruiters, and more. It could be big. Who knows? It might even work.

This post was originally published on Common Dreams.

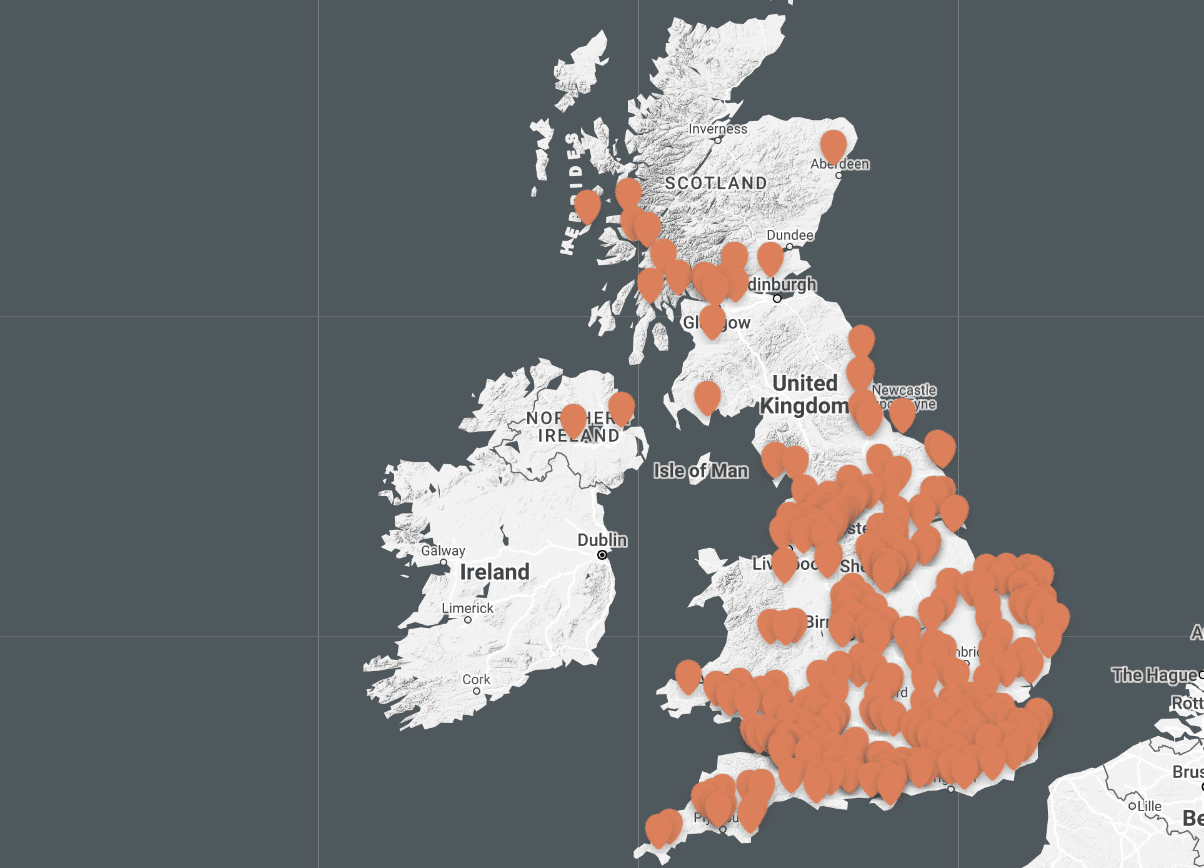

(@theAliceRoberts)

(@theAliceRoberts)

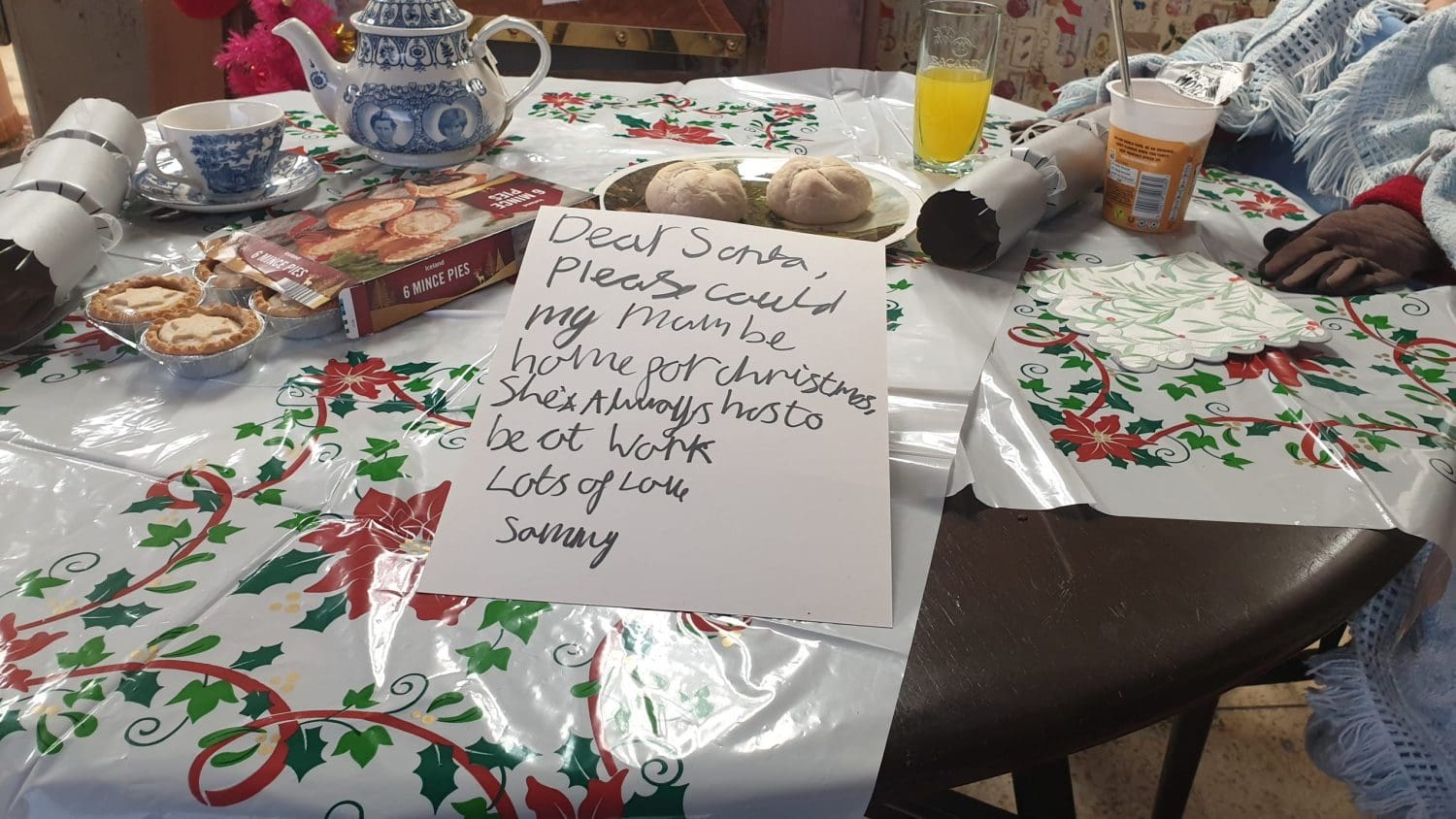

Photo: Jess Hurd Photography

Photo: Jess Hurd Photography