ANALYSIS: By Aprila Wayar and Johnny Blades for The Diplomat

A plan to create three new provinces in the Papua region highlights how Jakarta’s development approach has failed to resolve a long-running conflict.

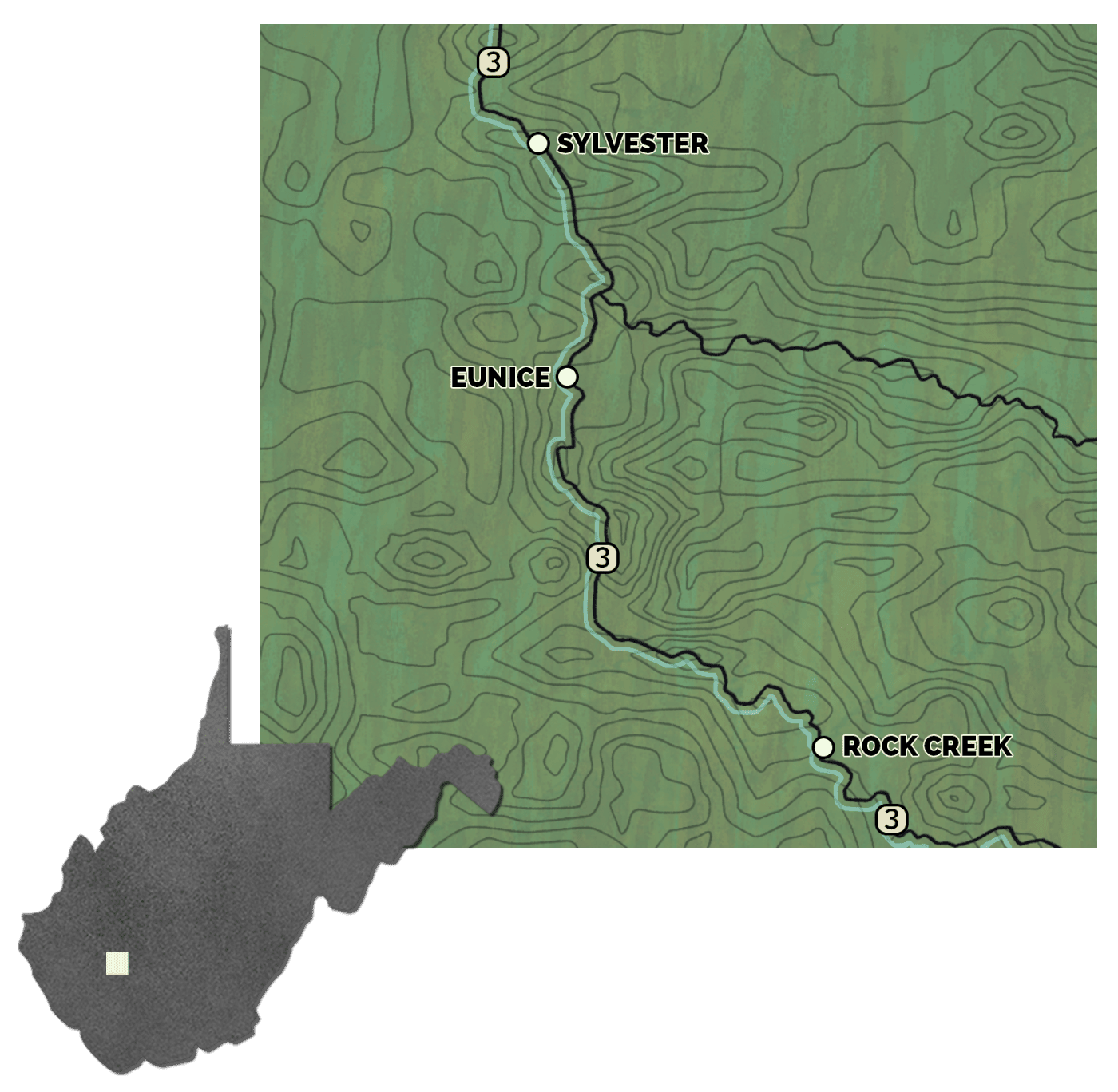

In April of this year, Indonesia’s Parliament approved a plan to create three new provinces in Papua, the easternmost region of the archipelago.

Government officials have described the creation of the new administrative units as an effort to accelerate the development of the outlying region, which has long lagged behind the other more densely populated islands.

But Papua’s problem isn’t a lack of development — it’s a lack of justice for West Papuans.

In the plan to subdivide Indonesia’s two most sparsely populated provinces — Papua and West Papua — many people sense a kind of “end game” strategy by Indonesia’s government that is expected to worsen the long-running conflict in Papua, something countries in the region can ill afford to ignore.

The province plan comes in the twilight of President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo’s second and final term in office, a term marked by an escalation of violence between fighters of the pro-independence West Papua National Liberation Army (TPNPB) and the Indonesian security forces.

Jokowi has ordered huge military operations in the central regencies of Nduga, Puncak Jaya, Intan Jaya, Maybrat and regions near the border with Papua New Guinea (PNG).

1960s armed wing

The TPNPB is the armed wing of the Organisasi Papua Merdeka (OPM), or Free Papua Movement, which was created in the 1960s by so-called West Papuan freedom fighters.

They opposed the Indonesian Army, which had begun occupying parts of West Papua after the Dutch withdrew in 1962, even before the United Nations Temporary Executive Authority had completed its period of mandated administration in 1963.

After Papua officially joined Indonesia in a 1969 UN referendum that many Papuans view as flawed, the OPM grew rapidly in the late 1970s, with fighters joining its ranks across West Papua. Their operations mainly consisted of attacking Indonesian patrols.

In 1984, when a West Papuan insurgent attack sparked large Indonesian military deployments in and around the capital Jayapura, the subsequent brutal sweep operations triggered a mass exodus of around 10,000 Papuan refugees to PNG.

At the time, when questioned in Jakarta about the impacts of military operations in Papua, a leading Indonesian Foreign Ministry official shrugged it off and stated that the government was introducing colour television in Papua and was doing its best to accelerate development there.

Nearly 40 years later, with the Papuan conflict reaching a new pitch of tension, the government’s narrative has barely changed.

Conflict continues at the cost of mass displacement in Papua’s highlands. Human rights bodies have stated that intensified bursts of fighting between TPNPB guerrillas and the Indonesian army since late 2018 have displaced at least 60,000 Papuans.

Figures hard to verify

Exact figures remain difficult to verify because Jakarta still obstructs access to the region for foreign media and human rights workers. Since the Indonesian takeover of Papua in the 1960s, West Papua’s history has been marked by persistent human rights abuses.

In recent years, the UN Human Rights Commissioner has repeatedly pressed for access to the region, without success.

In April, Jokowi’s cabinet, including Home Affairs Minister Tito Karnavian, a former police chief, and fellow hardliner Defence Minister Prabowo Subianto, introduced a draft for a long-anticipated creation of three new provinces — Central Papua, South Papua, and Central Highlands Papua –– in addition to the two existing provinces of Papua and West Papua.

This initiative has met with strong opposition from indigenous Papuans. Well before the recent cabinet decision, Papua’s provincial Governor Lukas Enembe warned against it, fearing new provinces could pave the way for more transmigrants and more problems for Papuans, although in recent days he has reportedly offered qualified support for dividing Papua based on customary territories.

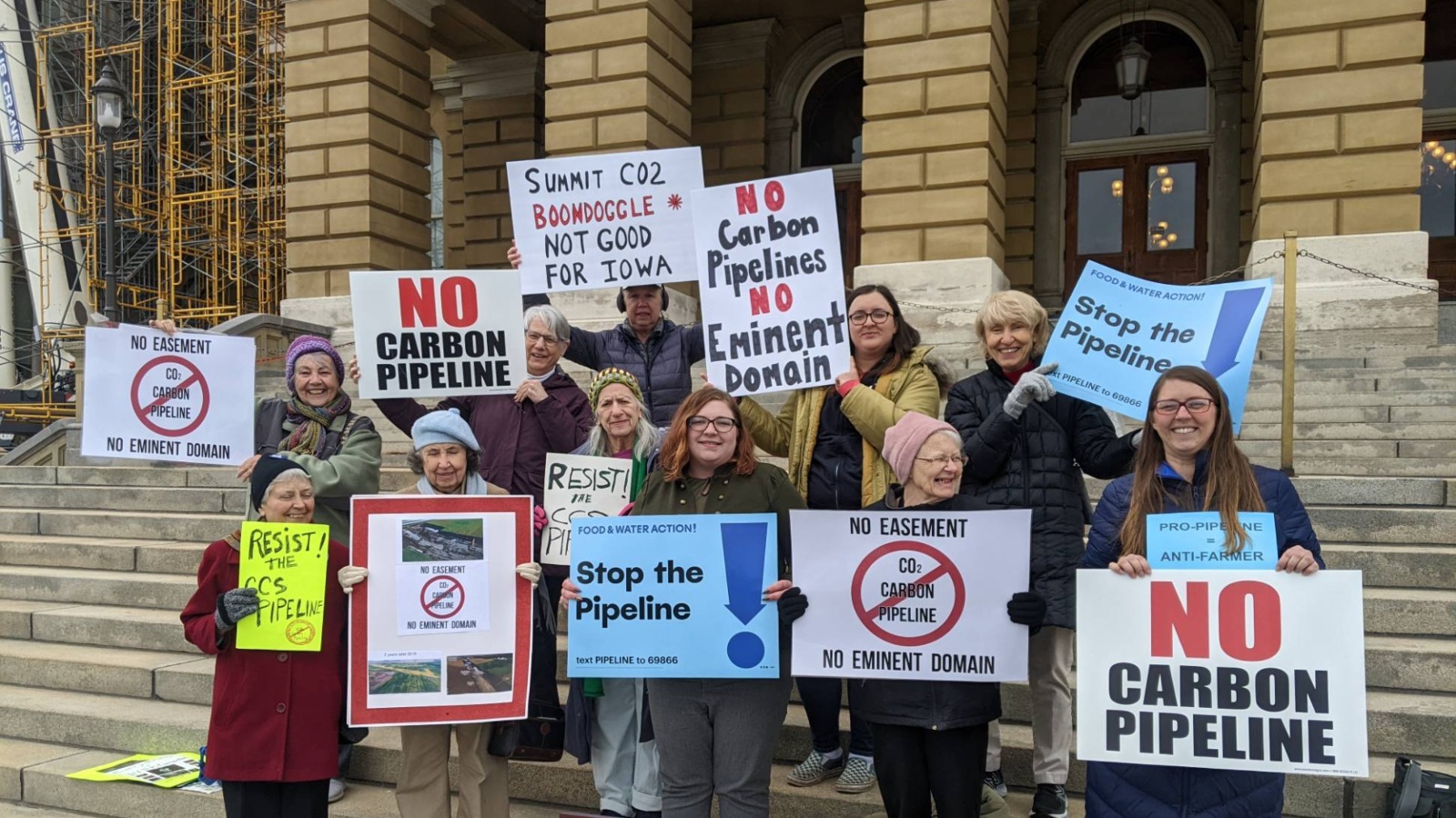

He was not alone in speaking up. On May 10, thousands of Papuans from the Papuan provinces and in major cities in other parts of Indonesia took to the streets to protest Jakarta’s creation of extra provinces.

Protests were met head on by heavy security forces responses including the use of water cannons and detention. Papuans were frustrated because their views had not been incorporated in Jakarta’s decision making.

As Emanuel Gobay, director of the Papua Legal Aid Institute, told The Diplomat, the region’s Special Autonomy Law, passed in 2001, requires the central government to conduct a public survey starting from the village level to the head of districts where the expansion will be carried out.

“The central government has introduced the planned expansion policy on its own initiative, without any aspirations from the grassroots communities,” Gobay explained.

Delineated history

For years, the Indonesian government has characterised West Papua as being backward in terms of social and human development, claiming that it needs Indonesian help to advance.

Certainly, poverty has been a problem in Papua, but that’s not unique across the republic. Yet, for decades Papua was effectively isolated by central government, often leaving the public in the dark about what has been going on there.

The social media age has lifted the lid on Papua a little, stirring international attention intermittently. As part of Jakarta’s response, social media bots have been deployed across the internet, spreading state propaganda and targeting human rights workers, journalists, or anyone drawing attention to Papua.

The bots say everything is good in Papua, look at all the development happening, 3G internet, roads. In a sense, it’s true that infrastructure development has increased in recent years.

Compared to neighbouring PNG, Papua and West Papua provinces are well developed in terms of basic services and roads. But it’s not necessarily the sort of development that Papuans themselves want or need.

The lack of a genuine self-determination process in the 1960s remains a core injustice that holds Papua back. Since then, thousands of indigenous Papuans have lost their lives in what is considered one of the most militarised zones in the wider region. Some research puts the death toll as high as 500,000.

One of them was Theys Eluays, a tribal chief who became a figurehead for Papuan independence aspirations and a strong critic of the first plan to divide Papua into two provinces, until he was assassinated by members of the Kopassus special forces unit in 2001.

Military elite have major interests

Indonesia’s political elite and military establishment have extensive interests in Papua’s abundant natural resource wealth. The new provincial divisions would enable more opportunities for the exploitation of these resources, largely for the benefit of people other than Papuans themselves.

The new provinces would be merely the latest in a series of delineations imposed on Papua by others, a process that runs from the marking of the western half of New Guinea as a Dutch colony in the 1880s, to the contentious transferal of control of the territory to Indonesia in the 1960s, to Jakarta’s subsequent reconfigurations of the province, especially after the enactment of the Special Autonomy Law in response to Papuan demands for independence.

The plan for further subdivisions did not emerge overnight. It has been mooted for decades by Indonesia’s powerful Golkar party as a way to cement sovereign control of the restive eastern region. In the 1980s, proposals for dividing Irian Jaya, as it was then known, into as many as six provinces were fleshed out at national seminars on regional development and gained interest from elites in Jakarta.

Even in these early seminar discussions, Papuan representatives warned that provincial splits could have a negative impact on local indigenous communities, whose interests were clearly not represented in provincial subdivision plans.

Although the idea of provincial expansion in Irian Jaya ended up on President Suharto’s desk, it hadn’t got off the ground by the time he stepped down in 1998.

During the subsequent tenure of President B.J. Habibie, Papuan tribal and civil community leaders were among the “Team of 100″ Papuans invited to the presidential palace for a dialogue, during which they asked for independence. Habibie told the Team to go home and rethink its request.

During the term of President Abdurrahman Wahid, the spiritual leader of Nahdlatul Ulama, Indonesia’s largest Islamic organisation, West Papuans were granted the concession of being able to raise the banned Papuan nationalist Morning Star flag, on the condition that it be hoisted two inches beneath the flag of the Indonesian republic.

The administration of the next president, Megawati Sukarnoputri, initiated a law that granted Papua Special Autonomy status and created a second province, West Papua (Papua Barat) — the first splitting of provinces.

Local resentment

Since Papua became a part of the Republic of Indonesia, Jakarta has introduced various laws aimed ostensibly at improving the welfare of indigenous Papuans. These have overwhelmingly been met with suspicion and skepticism by the Papuans.

Special Autonomy is widely regarded by Papuans to have failed on the promise to empower them in their own homeland, where they instead continue to be victims of racism and human rights violations, and their indigenous culture is increasingly threatened.

Due to large scale exploitation of Papua’s natural wealth, Papuans have been losing access to the forests, mountains, and rivers which were essential to their people’s way of life for centuries.

International companies such as Freeport McMoRan, Rio Tinto, BP, Shell, and multinational oil palm players operate here in commercialising Papua’s mineral, gas, forestry and other resources. There is little consideration about the sustainability of indigenous customs, which has only added to the long list of Papuan grievances.

Now that Jakarta is drawing more administrative lines through this cradle of native rainforest and immense biodiversity, Gobay expects new provinces to have three major impacts.

“First, it will create an environment for more land grabbing. Either through the granting of mining permits to foreign exploration companies or through the construction of other additional government enterprises on customary land,” he said.

“Secondly, marginalisation of Papuans on their own land would only increase,” he added.

Thirdly, he expected a rise in human rights violations.

The Papuan People’s Assembly (MRP), a cultural protection body born from the Special Autonomy Law, has filed for a judicial review of the provincial subdivision plan with Indonesia’s Constitutional Court, and asked the House of Representatives in Jakarta to postpone the New Autonomous Region Bill for Central Papua, South Papua, and Central Highlands Papua.

The court is expected to hold a hearing in the next month.

Minorities in their own land

The provincial split is bound to accelerate the steady reconfiguration of Papua’s demographics.

“If we make a rough estimate, almost 50 percent of the population of West Papua is not indigenous anymore,” said Cahyo Pamungkas of the Jakarta-based National Research and Innovation Agency.

He noted that transmigrants from other parts of Indonesia not only dominated Papua’s local economy but also its regional politics. For instance, there remain only three native Papuan representatives out of 21 legislative members in Merauke district, where some 70 percent of the population are non-Papuans.

Pamungkas also disputed the recent claims of Indonesia’s coordinating minister for legal, political and security affairs, Mahfud MD, that 82 percent of Papuans supported the proposed province splits.

“The survey should have been opened to the public. Who were interviewed and how many respondents participated? What was the survey method?” he asked, adding that such misleading statements are likely to foster additional distrust in the government.

So too can repeated arrests of young Papuans for exercising their democratic voice. Esther Haluk, a democratic rights activist from Papua, was arrested by security forces during the May 10 protests.

“New provinces will pave the way for more new military bases, new facilities for security apparatus. More military, more opposition, more human rights violations. This is like reinstating the Suharto era all over again in Papua,” she said.

Sectarian tensions

Sectarian tensions between indigenous Papuans and Indonesian settlers remain a tinderbox, particularly since major anti-racism protests in 2019. A disturbing factor in the deadly unrest around those protests was the role of pro-Indonesian militias, recalling the violence-soaked last days of Timor-Leste prior to its independence in 2002.

More transmigrants could pave way for more conflict in Papua, and more conflict could potentially justify more military deployment, which adds to the climate of persistent human rights abuses against Papuans.

Haluk said newly arrived migrants are often favored by officials in being able to take up local privileges such as jobs within the public service and government, especially if they have relatives already in Papua. Many have also been able to buy land.

“This is a real form of settler colonialism, a form of colonization that aims to replace the indigenous people of the colonised area with settlers from colonial society,” she said. “In this type of colonialism, indigenous people are not only threatened with losing their territory, but also their way of life and identity that’s been passed down to them from generation to generation.”

Regional implications

By exacerbating conflict in West Papua, the provinces plan could also prove problematic for neighbouring countries, none more so than PNG. Through no fault of its own, PNG has long been lumped with spillover problems from the conflict in West Papua, including the movement of arms and military actors across the two regions’ porous 750km border, refugees fleeing from Indonesian authorities, and the displacement of village communities in the border area.

The covid-19 pandemic also showed that when things get bad on the western side of the border, the problem spreads to PNG, beyond the control of either government.

PNG leaders have cordial exchanges with Indonesian counterparts but the Melanesian government is all too aware of the power imbalance when it comes to the elephant in the room, West Papua.

PNG’s Petroleum Minister Kerenga Kua, who has previously travelled to Jakarta as a member of high-level government delegations, attested to the limited options available to PNG for addressing the West Papua crisis.

“PNG has no capacity to raise the issue,” Kua said. “We can express our concern and our grief and disappointment over the manner in which the Indonesian government is administering its responsibilities over the people of West Papua.

“However there’s nothing much else we can do, especially when larger powers in our region like Australia remain tight-lipped over the issue. Of what constructive value would it be for PNG to venture into that landscape without proper support?”

He added: “So we are very guarded about what we say, because there’s no doubt about the concern that we have in this country.”

Refugees there to stay

Kua says many West Papuans who came across the border as refugees are there to stay: “We don’t complain about that. We just feel that this part of the country is theirs as much as the other side of the island is theirs.”

PNG’s policy on West Papua, where it rarely exercises a voice, has left it looking weak on the issue. The most vocal of the leading political players in PNG, the governor of the National Capital District, Powes Parkop, says that for too long, PNG government policy on West Papua has been dictated by fear of Indonesia and assumptions that make it convenient for leaders to not do anything about it.

While PNG hopes the West Papua problem will go away, Indonesia’s government is also burying its head in the sand by portraying West Papua’s problems as a development issue.

“It’s a human rights issue and we should solve it at that level. It’s about the right to self-determination,” Parkop said.

“PNG holds the key to the future peaceful resolution of Papua. If we rise above our fear and be bold and brave by having an open dialogue with the Indonesian government, I’m sure we’ll make progress.”

Following upcoming elections in PNG, a new government will take power in early August. It’s unwise to bet on the result, but former Prime Minister Peter O’Neill is one of the contenders to take office, and he, more than incumbent James Marape, has been able to project PNG’s role as a regional leader among the Pacific Islands.

He is also one of the few to have expressed strong concern about human rights abuses and violence against West Papuans.

‘Hope government will be brave’

“I hope the new government will be brave enough and have a constructive dialogue with Indonesia’s government so we can find a long-lasting solution,” Parkop said.

“As long as Indonesia and PNG continue to pretend it won’t go away, it will only get worse, and it is getting worse.”

Parkop added that because of the huge economic potential of New Guinea, “the future can be brighter for both sides if the problem is confronted with honesty”.

According to Kua, Indonesia’s government made a commitment to empowering Papuans to run their own territory within the structure of the Republic, a pledge which should be honored. Regional support would help encourage Indonesia in this direction.

“Australia, New Zealand, PNG, those of us from the Pacific all have to stand united until some other wholesale answers are found to the plight of the people of West Papua,” he said. “The interim relief is to continue to press for increased delegated powers to (Papua). So they have more and more say about their own destiny.”

The Papuan independence movement has managed to gain a foothold in the regional architecture, most notably with the admission of the United Liberation Movement for West Papua (ULMWP) to the Melanesian Spearhead Group regional bloc, whose founding aim is the decolonisation of all Melanesian peoples. But Indonesia’s successful diplomatic efforts in the region have provided a counterweight to regional calls for Papuan independence.

However, 2019 saw a rare moment of regional unity when the Pacific Islands Forum, which is made up of 18 member countries, including French territories New Caledonia and French Polynesia, resolved to push Indonesia to allow the UN Human Rights Commissioner access to Papua to produce an independent report on the situation.

Human rights unity stalled

Then the pandemic came along and the matter stalled.

“Following that, the Pacific Island states who are members of the ACP (African, Caribbean and Pacific bloc) supported the same resolution at (its) General Assembly in Kenya,” said Vanuatu’s opposition leader Ralph Regenvanu, who was foreign minister at the time of the Forum resolution. Since then, he said, there had been “nothing explicit.”

Papua remains of great concern to Pacific Islanders, Regenvanu explained, noting that Indonesia’s plan for new provinces was set to cause “accelerated destruction of the natural environment and the social fabric, more dissipation of the political will.”

The Papua conflict has fallen largely on deaf ears in both Canberra and Wellington, each of which is hesitant to jeopardise its relations with Indonesia. Australia’s new Prime Minister Anthony Albanese visited Jakarta soon after coming to power last month, showing that the country’s relationship with Indonesia is a priority.

But as the conflict worsens in neighboring West Papua, Australia’s involvement in training and funding of Indonesian military and police forces who are accused of human rights violations in Papua grows ever more problematic.

Under Albanese, Canberra is unlikely to spring any surprises on Jakarta regarding West Papua, but neither can it ignore the momentum for decolonisation in the Pacific without adding to the sense of betrayal Pacific Island countries feel towards Canberra over the question of climate change.

Major self-determination questions are pressing on its doorstep, both in New Caledonia, where the messy culmination of the Noumea Accord means the territory’s future status is uncertain, and in Bougainville where 98 percent of people voted for independence from PNG in a non-binding referendum in 2019.

Ratifying the referendum

PNG’s next Parliament is due to decide whether to ratify the referendum result, and while political leaders don’t wish to trigger the break-up of PNG, they know that failure to respond to such an emphatic call by Bougainvilleans would spell trouble.

While in Parkop’s view Bougainville and West Papua are not the same, there are lessons to be drawn from the two cases.

“In the past PNG has been looking at (Bougainville) from the development perspective, and we have tried so many things: changed the constitution, gave them autonomy, gave them more money, and so on.

“It did not solve the problem,” he said. “And now in PNG, it’s a reckoning time.”

He added: “So the Indonesians have to come to terms with this. Otherwise if they only see this as a development issue, they will miss the entire story, and it can only get worse, whatever they do.”

Much is riding on the Bougainville and New Caledonia questions, and fears that China could step in to back a new independent nation are part of the reason why Australia would prefer the status quo to remain in place, and probably the same for West Papua and Indonesia.

The 2006 Lombok Treaty between Indonesia and Australia, which prohibits any interference in each nation’s sovereignty, makes it hard for Canberra to speak out. But it could also play into China’s hands if Australia and New Zealand keep ignoring the requests of Pacific Island nations about West Papua.

Opportunities for resolution

Means of resolving the Papua conflict exist, but they aren’t development or military-based approaches. And as far as Jakarta is concerned, independence is out of the question.

Professor Bilveer Singh, an international relations specialist from the National Singapore University, told The Diplomat in 2019 that West Papuan independence was a pipe dream. Internal divisions among the Papuan independence movement are identified as a barrier.

The head of the ULMWP, Benny Wenda, sought to address this with decisive leadership by declaring an interim government of West Papua last year, but the move was criticised by some key players in the movement.

While Papua is unlikely to be another Timor-Leste, Singh wrote, an Aceh or Mindanao model with greater autonomy would be more achievable. Furthermore, Jakarta could allow Papuans to hoist their own colors under Indonesian sovereignty.

Declaring tribal areas as conservation regions is an option, too. More significantly, Papua could also become a self-governing state in free association with Indonesia, like the Cook Islands and Niue are with New Zealand, or even follow the model of Chechnya in Russia.

To be able to manage their own security and governance, and allow their culture to thrive, would answer a lot of Papuans’ grievances. A non-binding independence referendum, as PNG has allowed for Bougainville, would be a good starting point.

If Papuans are as content with Indonesian rule as Jakarta claims, a referendum would be instructive.

Meaningful dialogue necessary

At the very least, in a bid to stop the conflict, meaningful dialogue is necessary. Jokowi has reportedly given approval for Indonesia’s national human rights body to host a dialogue with pro-independence factions, including those residing abroad.

Leaders of the TPNPB and ULMWP have indicated they are interested in a dialogue only on condition that it is brokered by a foreign, neutral third party mandated by the UN.

The Papuans aren’t in a position to dictate such terms, unless international pressure weighs into the equation. They are however also highly unlikely to stop resisting Indonesian rule while their sense of injustice remains.

“The Papuan conflict is not about colour television or 3G internet, it’s about indigenous dignity and a stand against militarism,” Haluk said.

As well as drawing new lines on the map, the plan for more provinces in Papua draws a new line in the sand, beyond which the conflict in Indonesia’s easternmost region will become much more intractable.

No amount of development will stop this until Jakarta shifts its thinking on how to address the region’s core problem. The opposite of poverty isn’t wealth, it’s justice.

Co-authors and journalists Aprila Wayar (West Papua) and Johnny Blades (Aotearoa New Zealand) are contributors to The Diplomat. Republished with permission by the authors.

This post was originally published on Asia Pacific Report.

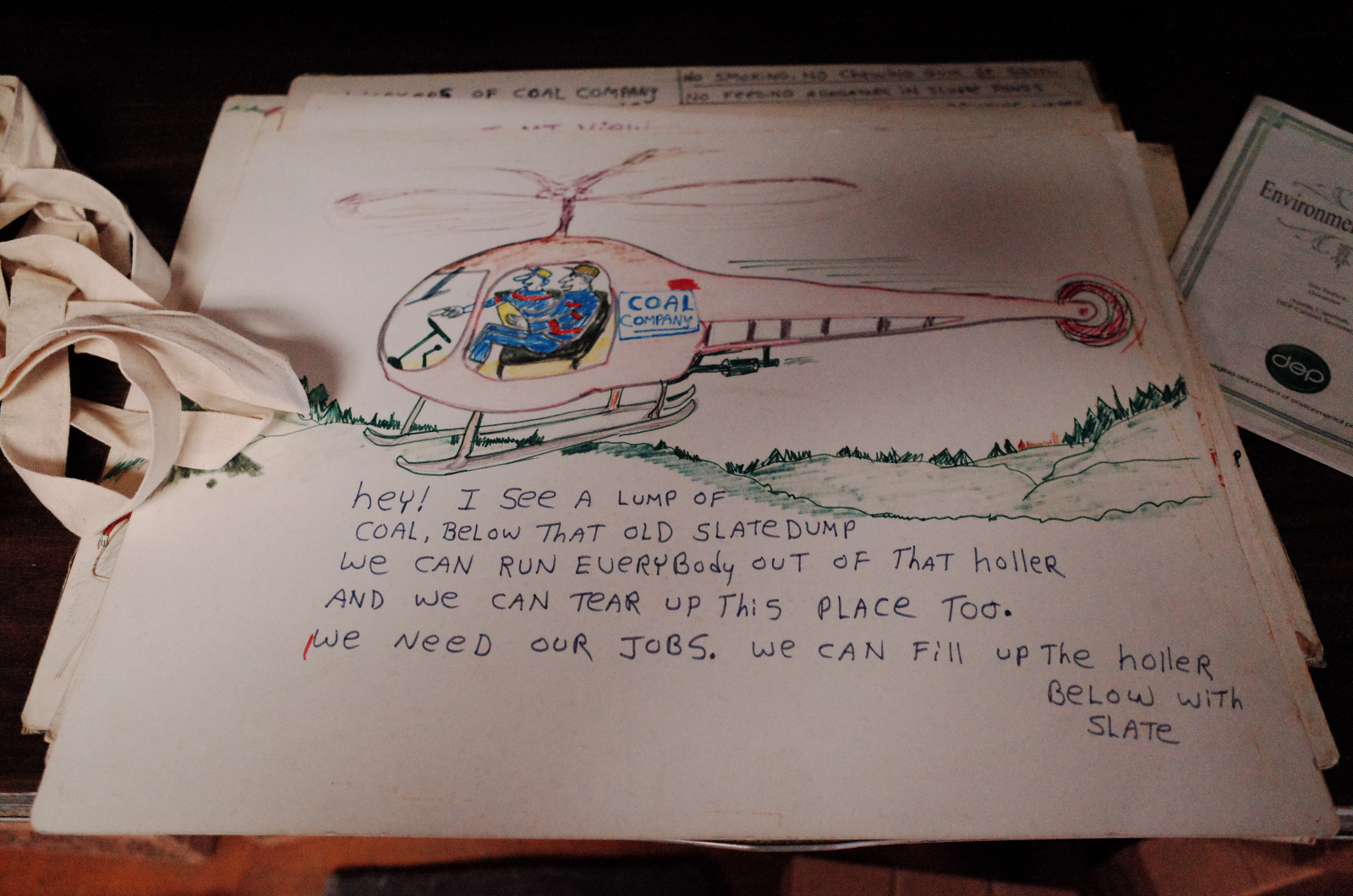

(screen shot sent to us by someone who is pledging to strike on Oct 1st).

(screen shot sent to us by someone who is pledging to strike on Oct 1st).