This content originally appeared on AlternativeRadio and was authored by info@alternativeradio.org.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on AlternativeRadio and was authored by info@alternativeradio.org.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty and was authored by Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty and was authored by Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty and was authored by Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Comprehensive coverage of the day’s news with a focus on war and peace; social, environmental and economic justice.

The post The Pacifica Evening News, Weekdays – July 12, 2024 Biden campaigns in Detroit as debate rages over whether he should stay in the race. appeared first on KPFA.

This content originally appeared on KPFA – The Pacifica Evening News, Weekdays and was authored by KPFA.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

As the world watched Thursday night, President Biden held his first solo press conference this year, after hosting a NATO conference in which he accidentally referred to Ukrainian President Zelensky as Russian President Putin before quickly correcting himself. While speaking with reporters, Biden defended his record and vowed to “finish the job,” but at one point referred to Kamala Harris as “Vice President Trump.” As more Democrats continue to call for him to step aside, we host a roundtable discussion on Biden and Trump and the 2024 race, and the impact on U.S. foreign policy, with American Prospect executive editor David Dayen; longtime labor, racial justice and international activist Bill Fletcher Jr., co-founder of the Ukrainian Solidarity Network; and CodePink co-founder Medea Benjamin, co-author of the books NATO: What You Need to Know and War in Ukraine: Making Sense of a Senseless Conflict.

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Princeville, North Carolina, the oldest community in the United States founded by formerly enslaved people, has been trapped in a cycle of disaster and disinvestment for decades. The town of around 1,200 people sits on a plain below the banks of the Tar River, and it has flooded more than a dozen times in the last century. The two most recent hurricane-driven floods, in 1999 and 2016, have been the most devastating in the town’s history.

In the aftermath of Hurricane Matthew, which submerged the town under more than 10 feet of water eight years ago, Princeville’s residents debated three distinct options: staying put on the town’s historic land, taking government buyouts to relocate individual families elsewhere, or moving the town itself to higher ground. But internal disagreements and a lack of funding made it difficult for the town to move forward with any of those choices in a comprehensive way. As a result, the damaged town hollowed out as residents and businesses left one by one, becoming yet another example of how slow and painful disaster recovery can be for rural and low-income communities.

Now, almost a decade after Hurricane Matthew’s devastation, Princeville’s fate is becoming clear — for better and for worse. The town has just received millions of dollars in new funding from the Federal Emergency Management Agency, or FEMA, to build a new site on higher ground, offering hope for a large-scale relocation. At the same time, a long-awaited levee project that promised to protect the town’s historic footprint has stalled out, making relocation harder to avoid as another climate-fueled hurricane season begins.

The idea to relocate the town first emerged after Hurricane Matthew, when the state of North Carolina helped Princeville buy 53 acres of nearby vacant land. The state also kicked in money to help town leaders plan a mixed-use neighborhood with new apartments and businesses, and it later bought another larger parcel adjacent to the 53-acre tract. Earlier this month, FEMA officials announced that they will send almost $11 million to Princeville to build out the stormwater infrastructure for the new town. Construction could begin before the end of the year.

When the development is done, it will contain the seeds of a new town center for Princeville. There will be a fire station and a town government building, as well as 50 new subsidized apartments to replace a public housing complex that was destroyed during Hurricane Matthew. Town officials are hoping that private developers will build dozens of single-family homes and businesses on the tract. This would make the 53-acre development almost as large and well-appointed as the old Princeville, with as many stores and almost as many homes.

When he announced the new funding, FEMA administrator Robert Samaan praised “Princeville’s commitment to build outside of the floodplain and protect their community,” saying the decision to move to higher ground “is a testament to their resilience.” But this was somewhat misleading: Many residents and town leaders, including the mayor, have sought for years to stay put on the town’s original flood-prone site. In 2016, Jones even tried to turn down a federal program to buy out flooded homeowners in the old town.

“We’re open to expansion, but we are not going to leave,” said the town’s mayor, Bobbie Jones, in an interview with Grist.

But that option looks less viable than ever. Those who wanted to protect historic Princeville have long held out hope that the federal Army Corps of Engineers would repair and expand the old levee that defends the town from the caprices of the Tar River, whose overflowing banks have long been responsible for Princeville’s woes. The Corps’s original levee contained critical flaws that caused it to fail during floods in 1999 and again in 2016, but it took the agency until 2020 to secure funding from Congress to build a new and larger levee.

Jones touted this new levee project as proof that historic Princeville could survive, but earlier this year the Corps told residents that it was going back to the drawing board to review the project. The agency had discovered that building the planned levee would inadvertently cause flooding in the larger nearby town of Tarboro, on the other side of the Tar River. Officials said they couldn’t reduce flood risk in one place only to increase it in another. This is a cruel historical irony: The founders of Princeville only got access to the low-lying land in the 19th century because the white residents of Tarboro deemed it too flood-prone to use.

“Here we are in the midst of hurricane season again, and we’re just praying,” said Jones.

In response to questions from Grist, a spokesperson for the Corps said the agency is committed to flood protection in Princeville and is seeking funds that would allow it to commission a report looking at other options beyond the levee.

The setbacks on the levee project, combined with the sudden burst of progress on the new 53-acre development, seems to provide a bittersweet answer to the murky question of how Princeville will adapt to climate change. When it is complete, the new development will give Princeville a path toward long-term resilience, one that doesn’t require keeping most residents on land that’s destined to flood. But even this progress has come at great cost: Almost eight years after Matthew, many displaced residents have moved on for good, and even the promise of a new Princeville on higher ground may not be enough to draw them back.

“I understand the government moves slow,” said Calvin Adkins, a former resident of Princeville who took a government buyout and now lives across the river in Tarboro. “But when you’re talking about such a historic town, I just — in my heart of hearts, I was hoping that these things could have been done earlier.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Climate change has forced America’s oldest Black town to higher ground on Jul 10, 2024.

This post was originally published on Grist.

Comprehensive coverage of the day’s news with a focus on war and peace; social, environmental and economic justice.

The post The Pacifica Evening News, Weekdays – July 5, 2024 Biden campaigns in Wisconsin, defiantly vows to stay in the race and win. appeared first on KPFA.

This content originally appeared on KPFA – The Pacifica Evening News, Weekdays and was authored by KPFA.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Chris Lehmann, D.C. bureau chief for The Nation, discusses the ongoing fallout from Thursday’s first presidential debate of 2024 and mounting pressure on President Biden to drop out of the race amid questions about his age and mental fitness. “It appears that Biden and his inner circle of advisers are doubling down,” says Lehmann. “They took this incredible risk to do this debate … and they’re now saying it’s a greater risk to change horses.”

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Our new three-part series launches June 15th, exploring the legacy of America’s broken promise to formerly enslaved Black people.

This post was originally published on Reveal.

Note: This episode contains descriptions of violence and suicide and may not be appropriate for all listeners.

In 1989, Chuck Stuart called 911 on his car phone to report a shooting.

He said he and his wife were leaving a birthing class at a Boston hospital when a man forced him to drive into the mixed-race Mission Hill neighborhood and shot them both. Stuart’s wife, Carol, was seven months pregnant. She would die that night, hours after her son was delivered by cesarean section, and days later, her son would die, too.

Stuart said he saw the man who did it: a Black man in a tracksuit.

Within hours, the killing had the city in a panic, and Boston police were tearing through Mission Hill looking for a suspect.

For a whole generation of Black men in Mission Hill who were subjected to frisks and strip searches, this investigation shaped their relationship with police. And it changed the way Boston viewed itself when the story took a dramatic turn and the true killer was revealed.

This week on Reveal, in partnership with columnist Adrian Walker of The Boston Globe and the “Murder in Boston” podcast, we bring you the untold story of the Stuart murder: one that exposed truths about race and crime that few White people in power wanted to confront.

To hear more of The Boston Globe’s investigation, listen to the 10-part podcast “Murder in Boston.” The HBO documentary series “Murder in Boston: Roots, Rampage, and Reckoning” is available to stream on Max.

This post was originally published on Reveal.

This coverage is made possible through a partnership between WBEZ and Grist, a nonprofit environmental media organization. Sign up for WBEZ newsletters to get local news you can trust.

Celeste Flores can tell you the good news about living in Waukegan, Illinois: The air is safer to breathe now.

“Thankfully, we are no longer breathing coal being burned,” said Flores, a co-chair of Clean Power Lake County, or CPLC, an environmental justice organization serving the mostly Latino suburb about 40 miles north of Chicago. The explanation behind that is simple: The Waukegan Generating Station near the shore of Lake Michigan closed in 2022 after decades of pumping greenhouse gases into the atmosphere and coal ash into the ground.

Flores can also tell you the bad news: The toxic coal ash is still there, dangerously close to the groundwater.

But the explanation behind why the pollution remains in the ground is more complicated than shutting a plant down.

Coal ash is a cocktail of hazardous pollutants leftover from coal combustion. Across the country, plant operators dumped that heavy metal-laden sludge into holes in the ground, sometimes called ponds or impoundments. Sometimes these ponds are lined, and sometimes they aren’t. None of the ponds in Waukegan that are lined meet current state and federal standards.

In 2019, the state confirmed what advocates like Flores had long suspected: that coal ash had leached into nearby groundwater. Worse yet, the coal ash was stored right near Lake Michigan.

That same year, Flores helped push Illinois lawmakers to pass landmark coal ash regulation, which compelled managers of coal ash owners to submit plans to either clean up their operations or shut down.

About three years ago the Illinois Environmental Protection Agency (IEPA) finalized exactly how operators had to submit these proposals. But plans are on hold for securing the three coal ash storage pits in Waukegan. The IEPA hasn’t finalized permits for those sites, so they continue to threaten groundwater.

“When it comes to the implementation of these rules, it’s 2024 and we don’t have permits yet,” said Flores. “And I don’t think anyone was expecting that.”

Illinois set itself apart from the majority of the country when it finalized its coal ash rules back in 2021. Most states, save for a handful like North Carolina and Michigan, relied on 2015 federal guidelines designed to monitor and clean up only some coal ash residuals.

For years, the federal rule excluded inactive coal ash ponds and landfills from oversight. An analysis by Earthjustice found that the 2015 rules grandfathered in over 300 of these sites across 48 states. Illinois’ more protective mandate, however, brought them into the state’s regulatory orbit.

Even so, advocates say the forthcoming permits are dragging.

“The Illinois EPA has been reviewing these proposed permits for almost two years,” said Andrew Rehn, the director of climate policy at Prairie Rivers Network in Champaign. “And that’s, like, a long time for these permits to sit and just be under review.”

The Illinois EPA is currently reviewing 44 separate coal ash surface impoundment permit applications for 25 current or former power plant sites across the state. Earlier this month, two and a half years since the first permit applications were submitted, the agency issued its first two draft permits.

The agency said in a statement to Grist and WBEZ that, “due to the complexity of the information required in the applications, in most cases [the] Illinois EPA has requested additional information or clarification from the applicants.” The statement went on to say that it can take weeks to months to “gather additional information or to analyze groundwater modeling data.”

Coal power plants have sought to make exceptions for their permits and have effectively stalled the permit process until the Illinois Pollution Control Board is able to resolve the requests. According to the IEPA, this is the major holdup with the Waukegan permits.

Meanwhile, new federal regulations issued last week give the nation’s fleet of coal power plants and new natural gas plants an ultimatum: adapt or shut down. The power plants have eight years to come up with a plan to capture 90 percent of their greenhouse gas emissions or commit to closing by 2039.

Advocates with the Waukegan group see this long awaited move as a step closer to phasing out coal for good. Although the coal business is in decline, it still has an outsized role in driving climate change and polluting surrounding communities. More than half of the country’s carbon dioxide emissions from electric power generation are attributable to burning coal, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

Almost every coal power plant operator in the country is now staring down the same finish line in 2039. Included in the new rule are stricter safeguards for the coal ash pollution those plants will leave behind in the meantime.

“With the 2015 rules, there was a circle of ponds and landfills that were subject to regulation,” said Megan Wachspress, a staff attorney with the Sierra Club. “That circle of ponds and landfills and other dump sites just got bigger.”

Inactive coal ash ponds and landfills are now part of the family of coal ash dumps that the federal government demands operators monitor and clean up when they threaten water resources.

If it was just a coal plant in Waukegan, Flores said, her organization’s fight might be more manageable. “But there’s so many other things.”

There are five Superfund sites scattered in and around the north shore suburb. These are abandoned lots so contaminated with hazardous materials that the federal government has taken over cleanup. Pointing in several directions, Flores said there are Superfund sites immediately north, south, and west of the old coal plant.

And that means generations of Waukegan residents have had to struggle with medical problems and even premature death because of their toxic environment.

There’s no question for Flores about what comes next: The coal ash must be removed from the ground. But to do that, state and federal agencies need to pick up the pace.

“It’s about making sure that we know that we’re leaving behind a community that’s healthier than what we received,” Flores said.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Illinois passed a law to clean up coal ash 5 years ago. What’s taking so long? on May 3, 2024.

This post was originally published on Grist.

This coverage is made possible through a partnership with WABE and Grist, a nonprofit, independent media organization dedicated to telling stories of climate solutions and a just future.

In a case that could impact other lawsuits on voting rights, Black voters who sued over Georgia’s elections for key utility regulators are appealing their case to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Those elections for the Georgia Public Service Commission have been on hold for years and while last week a federal appeals court lifted an injunction blocking the elections from taking place, there is little chance the elections will happen this year.

Public Service Commissioners have enormous sway over greenhouse gas emissions because they approve how electric utilities get their power. They also set the rates consumers pay for electricity.

In Georgia, the commissioners have to live in specific districts. But unlike members of Congress who are only elected by residents of their district, the Georgia commissioners are elected by a statewide, at-large vote. A group of Black voters in Atlanta argued in a lawsuit that this violates Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act because it dilutes their votes, preventing them from sending the candidate of their choice to the commission.

In one example the plaintiffs cited, the former commissioner for District 3, which covers Metro Atlanta, “was elected to three terms on the PSC without ever winning a single county in District 3.”

That commissioner — along with four of the five current commissioners — is a white Republican. Georgia’s population is one-third Black, with a much higher proportion in District 3. Georgia voters elected Democrat Joe Biden and two Democratic U.S. Senators in 2020, and Atlanta voters tend to choose Democrats for seats ranging from mayor and city council to U.S. Congress.

A federal judge agreed with the plaintiffs in 2022 and suspended PSC elections until the state legislature could devise a new system. However, in November 2023, the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals reversed that decision.

The appeals court ruling took issue with the proposed fix of single-member district elections, arguing a federal court can’t overrule the state’s choice to hold at-large elections because it would violate the “principles of federalism.”

“It’s kind of an upside-down view,” said Bryan Sells, one of the lawyers for the plaintiffs. “What the 11th Circuit’s ruling says is that Georgia is allowed to discriminate against Black voters.”

The plaintiffs are asking the U.S. Supreme Court to overturn the appeals court decision, though there’s no guarantee the Supreme Court will take up the case.

In their petition for Supreme Court consideration, the plaintiffs argue that if it’s upheld, the appeals court decision “would upend decades of settled law and have a cascading effect far beyond the reach of this case.”

“[The appeals court panel] simply decided that whatever rationales Georgia might tender for the at-large scheme…automatically trump any amount of racial vote dilution, no matter how severe,” the petition argues. “If a State’s interest can prevail in this case, there is no case in which it won’t.”

The Georgia Secretary of State’s office declined to comment on the appeal.

In the meantime, PSC elections have been on hold since 2022, when the federal judge who found for the plaintiffs imposed an injunction blocking the Secretary of State from holding or certifying those elections. The 11th Circuit issued an order last week lifting the injunction, though its effect was not immediately clear.

Sells and a spokesman for the Secretary of State’s office both said they were reviewing the order. In a text message, Sells also expressed surprise at what he called “the court’s unilateral action that no one asked for.”

Under the injunction, elections for two PSC seats that were scheduled for November 2022 were canceled. Despite not facing voters, those commissioners continue to serve and vote on PSC decisions, including rate increases and the three new fossil fuel-powered turbines the commission just approved.

PSC elections are also not on the 2024 ballot. A third commissioner’s term will expire at the end of the year.

A bill that passed the Georgia General Assembly before the Supreme Court appeal was filed or the injunction was lifted lays out a schedule for elections to resume, still following the current model of statewide voting. Gov. Brian Kemp signed it into law last week.

The law schedules those elections to begin in 2025.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline How should Georgia elect key utility regulators? US Supreme Court asked to weigh in on Apr 24, 2024.

This post was originally published on Grist.

This coverage is made possible through a partnership between WBEZ and Grist, a nonprofit environmental media organization. Sign up for WBEZ newsletters to get local news you can trust.

Earlier this month, Paulina Vaca stood at the corner of Pulaski Road and 41st Street, one of Chicago’s busiest intersections for truck traffic.

“I’m seeing a sea of trucks,” said Vaca, who works with the Center for Neighborhood Technology (CNT). In less than 60 seconds, she counted eight trucks.

That was just the beginning. In less than one hour, about 430 trucks passed through the intersection she was monitoring in Archer Heights, a mostly Latino community on the Southwest Side of the city. She was joined by José Miguel Acosta Córdova, who works for a community group known as the Little Village Environmental Justice Organization.

The two organizations recently put out a report measuring the extent of the city’s truck traffic, counting trucks moving through one nearby suburb and 17 Chicago neighborhoods. Using sensors installed in 35 spots, they tracked the number of medium-and heavy-duty trucks that went past in a span of more than 24 hours. Over the course of a day, more than 5,100 trucks and buses were recorded in Archer Heights — the most of any neighborhood.

That data points to key questions that Chicago and Illinois need to answer, said Acosta Córdova.

“When are there too many warehouses and when are there too many trucks?” he asked.

That’s a question that goes beyond Chicago, which happens to be the largest freight hub in North America. Black and brown communities living near the industrial corridors of many urban areas are disproportionately paying for it with their health.

Vaca and Acota Córdova are not alone in their research on local traffic. Across the country, local groups are increasingly finding ways to quantify the extent of localized air pollution, transforming real-time data into useful information that neighbors can use to inform day-to-day decisions like whether or not to stay inside.

While state and federal agencies do actively monitor air quality, their networks are limited, according to a United States Government Accountability Office report published last month. The national ambient air quality monitoring system is not designed to pinpoint pollution hotspots. More and more, localized data is exactly what frontline communities are calling for in order to protect and advocate for themselves.

“They want to know better than what their pollution level probably is,” said James Bradbury, the director of research and policy analysis at the Georgetown Climate Center, a nonpartisan research institution that studies federal and state climate policies.

“They would like to have more granular and specific information that informs what’s happening in their communities,” Bradbury said.

Community air quality monitoring programs are taking off across the country, he added.

From Newark, New Jersey to the Bay Area, local organizations are counting trucks and installing small networks of air quality sensors to fill the gap left open by state monitoring systems. As of 2022, Bradbury added that the federal government funded over 130 community air monitoring projects nationwide to the tune of $53.4 million.

Freight continues to be a major economic juggernaut in the Chicago region, and it comes at a significant health cost. The Respiratory Health Association ranked Illinois fifth out of all states for the highest number of deaths from diesel engine pollution per capita in 2023.

Diesel is what, in large part, moves freight around, according Brian Urbaszewski, director of environmental health programs for the Respiratory Health Organization.

“What comes out of the tailpipe of those engines is a collection of air pollutants: everything from nitrogen oxides to fine particulate matter, and even carbon dioxide,” Urbaszewski said. Exposure to these pollutants are associated with a host of medical issues, ranging from respiratory to cardiovascular health impacts.

Acosta Córdova said Illinois needs to adopt tighter truck regulations that are already in use in California and several other states. These policies would raise emission standards for tailpipe pollution and set a path for zero-emission trucks.

Vaca said that this new trucking data she and her colleagues compiled won’t surprise longtime residents of the city’s industrial corridors. But it is hard evidence that she hopes will help convince elected leaders that air pollution is an issue of life or death.

“Having these numbers, it’s really crucial to then advocate for more electric vehicles,” Vaca said. “To use this to advocate against permitting more industry in areas where it’s already overburdened.”

More than 1,000 lives and over $10 billion could be saved annually if the Chicago region electrified approximately 30% of all light and heavy-duty vehicles, according to a study published last fall by researchers at Northwestern University.

“We found that the majority of the health benefits from those reductions in pollution occur in environmental justice communities or communities of color, or disadvantaged communities in Chicago,” said Daniel E. Horton, a professor of earth and planetary sciences at Northwestern.

Earlier this month, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency announced finalized federal emissions standards for heavy vehicles that would require manufacturers to limit pollution from heavy trucks beginning in 2030. It’s estimated the new policy will prevent a billion tons of greenhouse gas emissions from entering the atmosphere. But Acosta Córdova said the guidelines do not go far enough to address the climate crisis. In Illinois, it’ll be years before residents see relief from freight driven air pollution.

“The biggest thing we want to see out of this is more data collection,” Acosta Córdova said. “But, also eventually, [we want] a full transition to zero emission trucks.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Monitoring a ‘sea of trucks’ in Chicago on Apr 16, 2024.

This post was originally published on Grist.

This content originally appeared on The Real News Network and was authored by The Real News Network.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by Radio Free Asia.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Leisa Glenn spent decades living in the Fifth Ward, a historically Black neighborhood in Houston, known for having one of the city’s best views of downtown. Every July 4th, Glenn, 65, and her neighbors would stream out of their houses into the summer heat and crowd onto front porches to watch the fireworks display.

She remembers the smell of the barbeque pit charring hot dogs and how neighbors would gather on every surface outside to watch: on top of cars, in folding chairs, and on porch steps.

“To look at the skyline at night, downtown, every night in different colors, and when they light it up — it’s like nothing you’ve ever seen before,” said Glenn.

Over the years, however, this crowd got smaller and smaller. Neighbors fell sick. Others moved away.

Buried beneath the Fifth Ward and its neighboring community, Kashmere Gardens, is an expansive toxic plume of creosote derived from coal tar. Historically, creosote has been used in the United States to preserve wood such as railroad ties and utility poles; it has also been linked to health issues such as lung irritation, stomach pain, rashes, liver and kidney problems, and even cancer, according to the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry and the Environmental Protection Agency.

Glenn remembers the old Houston Wood Preserving Works plant in the neighborhood that sat adjacent to the Englewood rail yard, which is the biggest rail yard in the city and one of the largest in the Union Pacific system.

For decades, its creosote was ever-present in the community: Strong odors permeated the neighborhood. Kids swam in a lagoon filled with waste from the factory. And when it rained, a rainbow oil slick would coat the streets.

While the actual facility is long gone, shut down in 1984, the creosote plume it created persists. The site is currently owned by Union Pacific Railroad, which acquired it in a merger with the Southern Pacific Railroad in the 1990s.

Glenn can clearly recall when the cancer cases started. It was the early 1990s, and the first person on her street to get sick was Carolyn, only 35 when she died, according to Glenn.

“So it really started at the corner with Carolyn,” she said. As more people started getting sick, “it just started trickling down the street.”

When Glenn talks about the people who have passed away, she mentions there’s not enough time for her to name all of them. But she starts ticking off people on the list: Mr. CL, Ms. Osborn, Mr. Johnny, Ms. Barbara Beale, her former friend and collaborator, and, of course, her mother Lucill.

Finally, in her late 30s, Glenn left after dealing with ongoing stomach issues for years. She often experienced a combination of coughing and pain that would get so bad she would throw up. Sometimes she coughed up blood. To this day, she has to take medication.

In 2019, the Texas Department of Health and Human Services established three separate cancer clusters in the Fifth Ward and Kashmere Gardens. A 2021 report from the Texas Department of State Health Services established one childhood leukemia cluster, confirming what residents had been saying for years.

When it comes to creosote, “this was a very, very high exposure area,” said Loren Hopkins, chief environmental science officer for the Houston Health Department. “We know that exposure to these chemicals causes these cancers,” she told Grist.

She also noted that in cancer cluster studies, the only types of cancers investigated were ones known to be caused by creosote and other cancer-causing chemicals found at the Union Pacific Railroad site.

It’s hard to flesh out what illnesses are caused by past exposure to creosote from when the facility was open versus current exposure to the plume lurking beneath residents’ feet. The U.S. EPA is currently conducting comprehensive testing in conjunction with Union Pacific to understand these competing timelines and exposure risks. Testing could take up to a year to complete.

Last July, after years of pleas from residents and several scientific and public health studies, Houston’s City Council announced a plan to relocate residents. In September, it approved $5 million to help residents move away from the contamination. Then-Mayor Sylvester Turner celebrated the funding, but warned it needed to be just the beginning: His office estimated relocating all 110 lots on the plume would cost about $24 million. As of last summer, 10 families have signed up for the buyout plan.

Last month, Houston’s new mayor, John Whitmire, allocated the first $2 million of those funds to Houston’s Land Bank to begin relocations.

There is a long history in the United States of companies paying to relocate residents rather than cleaning up polluted communities, from Diamond, Louisiana to Detroit, Michigan. But it is a rarer case when a city steps in to remediate this company-caused harm. Public health and environmental justice experts told Grist that Houston may be one of the first major cities in the United States to facilitate residential buyouts not on the basis of a climate disaster, but because of pollution.

After years of residents in the area trying to get Union Pacific to come to the table to discuss remediating the area, the city took an unprecedented step of offering the voluntary buyouts to residents on its own dime.

That response “feels unique and somewhat novel, in the history of U.S. environmental justice movements,” said Manann Donoghoe, a senior research associate at the Brookings Institute. He also lauded how quickly the city seemed to acknowledge and act once the cancer clusters were established. “What’s most interesting for me, as somebody who writes about climate reparations, was to see the city’s response,” he said. “To see immediately the mayor coming out and saying that, ‘Yes, this is an injustice, this is something that should be addressed.’”

But with city money involved, concerns are being raised by members of IMPACT, a local group that advocates for the people who live near the creosote plume, about what will happen to the land once residents are relocated. Further complicating the issue is that no one is sure about the risk.

When current Fifth Ward resident Mary Hutchins, 61, looks around her neighborhood, it’s clear that things are changing. Streets have been resurfaced and there’s a new, massive residential and retail complex that opened last year in Fifth Ward, which includes a sprawling apartment complex with 360 units, nearly 250,000 square feet of office space, and over 100,000 square feet of retail, according to the Houston Chronicle.

Hutchins is concerned that just as plans have solidified for residents to relocate, this development could price the original homeowners out of the area — meaning that any future cleanups would only benefit newer residents.

“So people who once lived in this neighborhood, they could never come back here, never. Because they can’t afford it,” Hutchins said. “Now it’s like they’re building all around us — everything is up-and-coming.”

At a recent city council meeting, Steven David, deputy chief of staff for Mayor Whitmire, presented new research that confirmed what Hutchins had observed: Since 2019, the city has issued 88 permits for new construction of single-family homes and 17 permits for new multi-family homes. Another concerning development is that the incomingresidents weren’t warned about the cancer cluster. In response, Mayor Whitmire put a pause on development in the Fifth Ward. He also thinks the bill for cleanup should be funded by Union Pacific.

“They have to assist with the cleanup of the mess that they created,” he said.

Meanwhile, residents are left in limbo. Do they stay or do they go?

Houston’s Fifth Ward neighborhood is a part of the city’s original ward system. Founded after the Civil War by a racially mixed group of Black freedmen and white residents, by 1880 the neighborhood was predominantly Black and became an epicenter for Black culture in Houston.

Glenn, Hutchins, and others who grew up in the neighborhood describe it as extremely tight-knit.

“If your mom was gone all day, or had some business to take care of, you could always knock on the door and say, ‘My mom ain’t home,’” Glenn said. Whoever answered always invited you in.

“‘Okay, come on over here and go get the rest of ’em. Y’all gone eat.’” Glenn recounted. “It was a loving neighborhood.”

The memories of creosote are just as strong.

What angers Glenn was the silence in the wake of so many deaths, and the fact the neighborhood had to look for answers on their own.

“And nobody still didn’t say anything after all these people had died,” she said. “We just knew it was something, but we couldn’t figure out what it was.”

Glenn is the president of IMPACT. The group has been raising awareness of the issue since 2014, when she cofounded the group with Sandra Small, the former president who passed away in 2021 from cancer.

The group started by gathering residents to talk about what had happened to their neighborhood, but it evolved into organizing protests and attending public meetings to incite action. At its first protest, Glenn created the group’s unofficial mascot, creosote man: a skeleton with a T-shirt emblazoned with the words “Creosote killed me.” The group has used him ever since to raise awareness of lost neighbors and loved ones to cancer in the area.

IMPACT soon started to collaborate with scientists and the city, zeroing in on the old wood preservation plant as the likely source of the creosote contamination that was sickening residents. Next, IMPACT focused on finding solutions. The relocation option came out of early conversations with residents, according to Hopkins from the city’s health department.

She was present at those meetings in 2019 and remembers how important a voluntary buyout option was to residents.

“This was a request by the community,” said Hopkins, “and their reasons were not associated with a specific contamination level. It was associated with the stress and concern, and the devaluation and the injustice of it.”

Often the choice between staying and leaving isn’t much of a choice. Most of the people located in this part of Houston grew up here, in houses that were passed down from generation to generation.

Reverend James Caldwell grew up in the Fifth Ward; his parents moved there in the early 1950s. He spent years as an assistant pastor at the Fifth Ward Baptist Church. He now is associated with the St. Mark Missionary Baptist Church in Humble, Texas.

In 2008, he founded the Coalition of Community Organizations, or COCO, in Houston, an organization that calls for action on environmental injustice, disaster recovery, and fair housing in Houston.

“The creosote issue, it has been decades old, decades,” Caldwell said. “It’s nothing new. A lot of lives have been lost. And there are still a lot of illnesses, sicknesses as a result of it.” He’s lost two people to cancer in the area, including former IMPACT member Barbara Beale and a friend who died at 11 from childhood leukemia.

Caldwell lists all the burdens put upon the people of the Fifth Ward and Kashmere Gardens: the cancer clusters, the reluctance of Union Pacific to do cleanup, the years of begging someone to do something.

“Do you have to lose your history, your culture, or your identity in that process?” Caldwell asked.

Denae King, the associate director of the Bullard Center for Environmental and Climate Justice at Texas Southern University, grew up in Kashmere Gardens.

You have to take racial inequities into account, she said, when you ask people in her old neighborhood to leave their homes.

“In the Black community, it’s quite an honor to own property, to have property be passed down from your grandparents or your parents,” King told Grist.

That is going to weigh on the minds of the residents who have to decide whether to stay or go. It would be hard not to think, “But my family fought hard and my parents worked hard to buy this property,” she said.

Robert Bullard, founder of the Bullard Center at Texas Southern University, has studied the links between race and toxic pollution for over 50 years. His first seminal work, which established him as the father of environmental justice, focused on landfill-associated pollution in Houston in 1979.

Given his deep ties to the city, he understands what’s at stake when a community is contaminated — and even more so when it is threatened to be torn apart.

“Relocation means loss of community and loss of neighborhoods, loss of familiarity, of one’s history,” Bullard said. “It’s very hard to leave a community that you grew up in, and you thought was going to be your homestead and your American dream.”

The city’s plan to relocate residents away from the toxic creosote plume was the result of years of careful planning, collaboration, and conversations with the community, according to Hopkins.

Union Pacific, which has owned the land for more than 25 years, has so far denied all responsibility for illnesses in the community. Last year, the company narrowly interpreted data released by the state as having found no cancer risk, according to the Houston Chronicle. A spokesperson for the Texas Department of State Health Services told the Chronicle that the results of the report “should not be considered a comprehensive assessment.”

In a comment to Grist, Union Pacific noted its current testing collaboration with the EPA to study air and soil contamination at the former Houston Wood Preserving Works site, and said it remains dedicated to understanding the pollution risk and conducting remediation. “Since inheriting the site in a 1997 merger with Southern Pacific, we have completed extensive remediation and cleanup,” a Union Pacific spokesperson said in an email, referring to work done at the site of the former wood preserving plant.

“While the latest round of testing is underway, our collaboration with the Fifth Ward community, the City of Houston, Harris County, and the Bayou City Initiative remains active and steadfast, and we will maintain transparency and open communication throughout the process.”

The results of testing will prove vital to the community’s next steps. Many residents are caught between having to stay and wanting to stay. Houston is an expensive city to live in, Glenn says, and many of the neighborhood’s longtime residents are at retirement age, and therefore living on fixed incomes.

“A lot of them ain’t choosing to stay there. They have to stay there,” she said.

For Hutchins, she just wants to be sure she knows her risk before leaving her home.

“If it’s not safe [in the Fifth Ward] then of course I wouldn’t want my grandkids nor my daughter here,” Hutchins told Grist. “I believe we would need to get out.”

But she wants to be sure. She’s skeptical after seeing the revitalization happening in parts of her neighborhood, and is questioning the motives of people who might want to develop in the area, since the contamination is still an issue.

“Why would they waste their money and do that?” she said.

Even if residents do voluntarily participate in buybacks of their property, the question of where they will go next is difficult to parse. A Bank of America report published last year identified Houston as one of four cities that are experiencing housing shortages amidst rapid population influx as people seek to take advantage of robust economic opportunities. This could affect the city’s plan of helping residents locate new places to live.

The city is planning on using its land bank — a nonprofit group that recycles abandoned and condemned properties into new housing — to facilitate payouts and identify potential relocation spots for affected Fifth Ward residents.

The city also wants to provide support in securing health insurance for those affected by the cancer clusters, which could be one way that experts say Houston could lead the way with legacy pollution problems.

For residents, long-time activists, and politicians alike, this has been a long and arduous process.

“The relocation and the buyout and the payments for property and homes, it might sound like a success story,” said Bullard. “But that’s often not the end of the story. The end of the story is where will people find housing, replacement housing, within this area, where affordable housing is very limited.”

While the details of Houston’s relocation initiative remain in debate, from its timeline to its financing to its logistics, there’s one thing echoed across stakeholders: Residents, advocates, scientists, and politicians all want to see Union Pacific pay.

“We didn’t ask to be contaminated,” said Glenn. “We didn’t go over there bothering Union Pacific. Union Pacific bothered us.”

Glenn wants more aid for those affected, from top-of-the-line cancer care to assistance with everyday expenses.

“I hear some people say, ‘Well I ain’t got food, because I had to pay this bill and I had to get my medicine, I had to go to chemo,’” she added.

These bills add up and the community has been paying the cost literally and figuratively for decades. Residents of the Fifth Ward and Kashmere Gardens filed a $100 million lawsuit against Union Pacific in 2022 for wrongful death on behalf of deceased residents in the area. It eventually was ruled as abated in early 2023, the term for when lawsuits are halted because the suit cannot go forward in the form it was filed in.

“Union Pacific should have set up a fund — just a once-a-month fund to try to help them out with what’s going on,” she said.

City Council Member Tarsha Jackson, who represents the Fifth Ward, thinks a lot more could be done to address the problem, which has been decades in the making. She’d love to see the same political will aimed at helping residents in the Fifth Ward and Kashmere Gardens as there was for people affected by Hurricane Harvey.

“Harvey was a disaster,” she said. “In my opinion, this contamination, it’s a disaster.”

Hutchins, meanwhile, wants to see investment in revitalizing the area. She wants to see cleanup of the area on the table as a real option.

“I would love for this to be a community again. It’s like a ghost town,” said Hutchins.

But only, she said, “if it was safe for families to come back.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Industry poisoned a vibrant Black neighborhood in Houston. Is a buyout the solution? on Mar 6, 2024.

This post was originally published on Grist.

This coverage is made possible through a partnership between WBEZ and Grist, a nonprofit, independent media organization dedicated to telling stories of climate solutions and a just future. Sign up for WBEZ newsletters to get local news you can trust.

Naomi Davis won’t lose her faith in the earth. At a recent community meeting in Chicago’s South Side she wanted to drive the point home — that the city’s Black community will not be left out of the new, emerging green economy.

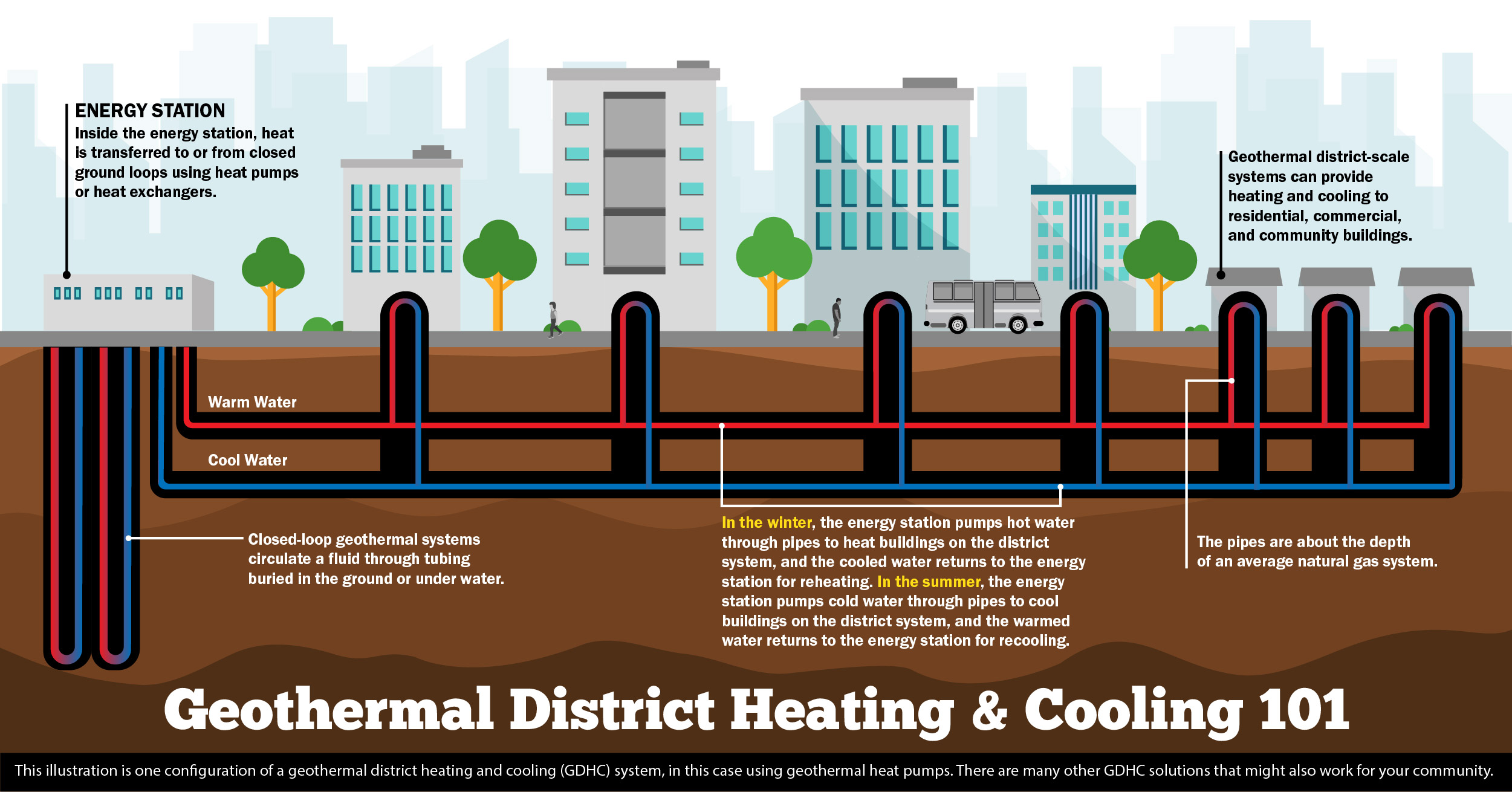

To do it, she’s betting on energy trapped deep below the surface of the earth known as geothermal, which could be an answer to heating and cooling homes more efficiently and a path to building decarbonization.

Davis heads Chicago’s Blacks in Green, an environmental justice group which has dedicated the past 17 years to figuring out the blueprint for self-sustaining, climate-resilient Black communities everywhere.

“We’re hit first and worst, resourced least and last, and we contribute the least to global warming,” said Davis.

Last year the group won the support of the Biden administration with the Environmental Protection Agency awarding a five-year $10 million grant. The money will enable Blacks in Green to work with other environmental justice communities in the Midwest to take advantage of historic funding made available through the Inflation Reduction Act.

The Chicago organization is already beginning to work on sustainability projects in Cleveland.

Back home, Davis is focused on carbon-free energy: how to generate it, how to make it affordable, and how to get it out of the ground. Her aim is to ensure that her community won’t be left behind as the rest of the city becomes sustainable.

“We’re not going to be the ones left on the gas bills with the spiraling costs and the technology that is continuing to pollute us,” she said, adding for emphasis, “No.”

In 2023, Blacks in Green was one of 11 community partners across the country chosen by the U.S. Department of Energy to design and develop a community geothermal heating and cooling district. That will mean building out a shared geothermal network across four city blocks containing more than 100 multi-family and single-family homes.

The goal is to decarbonize buildings and reduce energy costs for families. To get there, Blacks in Green received nearly $750,000 to kick off the initial phase of the pilot, which includes hosting community meetings and determining household needs.

Davis said Chicago’s West Woodlawn neighborhood — located about 9 miles south of the city’s downtown — is ready to experiment with geothermal energy.

But at the Blacks in Green community meeting, neighbors like Debra Gay and her mother Retta Ford have questions about what exactly it’ll take to bring geothermal energy to the South Side.

“Given that our city lots are so tightly spaced, how would you do that for an existing home and will that create some disruption?” asked Gay.

Ford, Gay’s mother, worried whether the project could destabilize the foundation of older homes.

Not necessarily, according to Andrew Barbeau, president of the Accelerate Group, a clean energy consulting firm working alongside Blacks in Green to design and deploy the geothermal pilot project.

The key to geothermal in these old neighborhoods: the alleys.

“Out in front, you got water, you got gas, you got sewer, and other things are alleys,” Barbeau said. “There’s nothing under that ground.”

The plan is to leverage the earth underneath the alleys behind homes and businesses to build out a community geothermal system. That will mean a series of deep, 400-foot holes that pipe water into the ground, absorb the temperature of the earth, and bring it back up to the surface to make use of it.

By building the community heating system beneath the alleys, the project sidesteps the major challenge that major American cities like Chicago face: lack of open, workable space. Once installed, buildings along the alleyway can connect to the underground heating system at their own convenience.

This all works because the earth functions as a kind of thermal battery. The sun beats down on the earth, and it absorbs some of that energy. So much so that between 20 and 40 feet below the surface of the earth, the temperature hovers consistently around 12.8 degrees C (55 degrees F) year round, according to Andrew Stumpf, a geologist with the Prairie Research Institute at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.

“So you circulate water in a pipe, and you exchange the heat from the pipe into the water, and you’re pulling that temperature out,” Stumpf said.

Experts call geothermal energy a nearly inexhaustible energy source, and it isn’t limited to just Chicago. It can be brought online almost anywhere. Back in 2019, the DOE released a study charting the path to massively scaling geothermal across the country. It found significant economic opportunity for geothermal district systems throughout the Midwest and Northeast, with Illinois, Michigan, Ohio, New York, and Pennsylvania leading the pack.

With 23 geothermal districts across the country, the U.S. lags behind Europe, where nearly 400 are in operation.

While the DOE is investing in geothermal districts which rely on the earth’s near surface temperatures, they’re also betting big on larger-scale enhanced geothermal systems, which typically require drilling miles underground. Enhanced geothermal works by pumping fluid deep into the earth, which is then recovered as steam and put to work to generate electricity.

Earlier this month, the Biden administration announced $60 million for three enhanced geothermal system pilots in California, Oregon, and Utah. An analysis from the DOE last year found that by advancing enhanced geothermal, the U.S. could be on track to generating 90 gigawatts of electricity, or enough to power 65 million homes by 2050.

Geothermal in West Woodlawn is a long way out. Once the community engagement phase wraps up, Blacks in Green will have the opportunity to be selected for up to $4 million in grants to actually go out and build the system.

But there are still major questions left. Who owns the geothermal network? Who decides the rates? West Woodlawn could develop public benefit corporations or local co-ops that share benefits with residents.

The hope isn’t just to break ground on geothermal but explore new ownership models that center equity along the way.

Back at the Blacks in Green meeting, resident Rosazlia Grillier said she thinks a lot about what people sacrifice when they’re unable to pay their energy bills. She said the more that people know about geothermal, the more likely they’ll be on board.

“Prices around energy costs are skyrocketing,” said Grillier. “And so we can either just complain about it, or we can educate ourselves about it and make the change that we know needs to happen.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline A geothermal energy boom could be coming to Chicago’s South Side on Feb 23, 2024.

This post was originally published on Grist.

This post was originally published on IndigenousX.

Last summer, Reveal host Al Letson returned home to Jacksonville, Florida, to find a changed state. The Republican Legislature had passed a slate of laws targeting minority groups. Educators could now face criminal penalties over the material they teach regarding gender and sexuality, and schools across the state were banning books about queer families, transgender youth and Black history. There were also repeated instances of racist and anti-Semitic speech, including Nazis waving swastikas in front of Disney World. All of this contributed to the NAACP issuing a rare travel advisory stating that “Florida is openly hostile toward African Americans, people of color and LGBTQ+ individuals.” Then on Aug. 26, a White supremacist killed three Black people at a Dollar General in Jacksonville.

When Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis attended a vigil for the victims, he was met with boos and mourners shouting, “Your policies caused this.”

In this episode, Letson digs into the policies DeSantis and the Legislature have passed in recent years and their effects on Black Floridians and other people of color. He speaks with a history teacher who says the new laws have made it harder to educate students, as well as a mother who describes books being removed from her daughter’s classroom and rules barring students from sharing books with friends at school. Letson also interviews state Rep. Randy Fine, a Republican who championed many of the new policies, including the Stop WOKE Act, which restricts how racism and history are taught in schools.

In the final segment, Letson examines redistricting in the state. In 2022, DeSantis vetoed maps drawn by the Republican Legislature, and the governor’s office instead drew new maps that got rid of two Black-dominated districts and increased the number of Republican-leaning districts. Those maps, which were subsequently passed by lawmakers, are now being battled over in both state and federal court. To understand the debate, Letson speaks with reporter Andrew Pantazi of the Jacksonville news organization The Tributary, as well as lawmakers on both sides of the aisle. Fine defends the new maps, saying they’re designed to challenge Florida’s Constitution, which he argues requires “racial gerrymandering.” Democratic state Rep. Angie Nixon says the new maps violate Florida’s constitutional protections of racial minorities and their ability to “elect representatives of their choice.”

Support Reveal’s journalism at Revealnews.org/donatenow

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter to get the scoop on new episodes at Revealnews.org/newsletter

This post was originally published on Reveal.

Seventeen groups issue statement sounding alarm at migration laws agreed by most EU members

The EU risks opening the door to increased discrimination and racial profiling in what is being described as a “potentially irreversible attack” on the international system offering asylum and refugee protection, human rights organisations have said.

Seventeen NGOs have together sounded the alarm before what is expected to be one of the final meetings on the text of a package of controversial new migration laws already agreed by most EU leaders.

Continue reading…This post was originally published on Human rights | The Guardian.

At the height of the Great Depression, when home foreclosures in the United States soared to 1,000 per day, the federal government adopted programs to keep people in their homes and make mortgages more affordable — just not for everybody. To determine who would get assistance, the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation, created as part of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, mapped out cities across the country in the 1930s. Appraisers ranked neighborhoods all over the country on a scale from Grade A to Grade D, drawing green lines around the neighborhoods deemed most desirable and red lines around the “hazardous” ones — essentially a code word for where ethnic minorities and especially Black people lived.

Even though “redlining” was banned in 1968, its legacy is still creating problems today, since urban planners saddled these neighborhoods with polluting industrial plants, airports, and highways. Historically redlined neighborhoods have fewer trees than richer neighborhoods and suffer more from air pollution and extreme heat. And according to a recent study published in Nature Ecology & Evolution, they are also subject to more noise pollution, often at volumes that pose risks to human health.

Researchers at Colorado State University, along with experts in New Mexico, New Hampshire, and the United Kingdom, analyzed how exposure to transportation noise aligned with maps of historically redlined neighborhoods, looking at the consequences for human health and urban wildlife. They found that the maximum noise levels in neighborhoods coded as Grade D by the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation back in the 1930s were 10 times higher than in Grade A neighborhoods, in terms of sound intensity.

While you might expect that the more crowded the city, the louder it would be, the research found that redlining grades predicted noise levels from traffic, trains, and planes even better than population size did. “What was striking to me was how clear those patterns were,” said Sara Bombaci, an author of the study and a professor of conservation biology at Colorado State University. Previous studies have found that noise pollution is worse in Black neighborhoods and in segregated cities as a whole, but the new analysis is the first to look at redlining specifically.

The Environmental Protection Agency recommends that noise levels stay below 70 decibels in order to avoid hearing loss. Nearly all redlined neighborhoods across 83 cities had maximum noise levels above that threshold, according to the study, as did most Grade A through C neighborhoods. Several redlined areas had maximum noise levels above 90 decibels, roughly as loud as a blender or power tools — a threshold that’s associated with hearing damage, higher stress levels, and physical pain. Only a handful of Grade A neighborhoods were exposed to that level of sound.

Not all noise is bad for your health — the sound of crickets, for instance, can reach up to 100 decibels, yet people still fall asleep to it. What stresses people out is “unwanted sound,” according to Erica Walker, an epidemiology professor at Brown University. Unexpected noises can disrupt your sleep and your mood and even trigger a fight-or-flight reaction. “This stress response is the same stress response that you would have if you’re walking down a dark alleyway and out jumps a man with a knife,” Walker said. Confronted with an irritating noise, your body releases stress hormones that put you at greater risk for cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, and mental health problems.

“Noise today is an artifact of poor urban planning policies,” Walker said, pointing to how governments built major highways right through longstanding Black communities.

According to data provided to Grist, the cities where redlined neighborhoods had the worst noise levels are Miami; New York; Austin, Texas; Chicago, San Francisco, and Denver, in that order. Some of those cities are just loud in general: In Miami and Chicago, even Grade A neighborhoods were subject to maximum noise levels above 95 decibels, Bombaci said.

Columbus, Georgia, had the quietest redlined neighborhoods, followed by Davenport, Iowa, and Jackson, Mississippi.

The researchers used data from the Department of Transportation that only considered noise from traffic, rail, and aviation. If noise from industry and construction were included, Bombaci suspects that the separation between Grade A and Grade D neighborhoods would be even more distinct.

Noise is often viewed as a first-world problem, Walker said, or simply a sacrifice of living near where things are happening. But there are plenty of ways that cities can reduce noise pollution, including lowering speed limits on roads and using quieter types of pavement to decrease friction with tires. Some cities, like Washington, D.C, have banned gas-powered leaf blowers, silencing their 80-decibel drone. The New York City Council is considering bills to minimize the blare of sirens on emergency vehicles.

But it’s not easy to move a highway or airport. “Once we go back and look at how urban planning and policies contributed to this, then we need to do justice,” Walker said. “And then we need to make sure that going forward, that we aren’t implementing policies and procedures without considering noise.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Where is noise pollution the worst? Redlined neighborhoods on Nov 30, 2023.

This post was originally published on Grist.

Human rights campaigners say the Pegasus initiative wrongly criminalises people of colour, women and LGBTQ+ people

Some of Britain’s biggest retailers, including Tesco, John Lewis and Sainsbury’s, have been urged to pull out of a new policing strategy amid warnings it risks wrongly criminalising people of colour, women and LGBTQ+ people.

A coalition of 14 human rights groups has written to the main retailers – also including Marks & Spencer, the Co-op, Next, Boots and Primark – saying that their participation in a new government-backed scheme that relies heavily on facial recognition technology to combat shoplifting will “amplify existing inequalities in the criminal justice system”.

Continue reading…This post was originally published on Human rights | The Guardian.

A national anti-racism framework, a Human Rights Act and discrimination law could all do a lot of good, especially for Indigenous Australians

Regardless of how Australians feel about the result of the referendum, it’s pretty clear the campaign was divisive and featured rhetoric that made Indigenous Australians feel unsafe.

Australia must now have a reckoning about how it can advance reconciliation and improve practical outcomes for Indigenous Australians without a voice.

Continue reading…This post was originally published on Human rights | The Guardian.