The emergence of the new Omicron strain of COVID-19 is alarming, even if the exact danger it poses is still unclear. This development should serve as a reminder of what’s been clear from the beginning of the pandemic — that the only way to suppress the virus’s spread is to have a truly global vaccination effort. The most obvious way to increase global vaccine access is for the World Trade Organization to adopt India and South Africa’s proposal to waive intellectual property rights of the giant pharmaceutical companies that are claiming a monopoly on vaccine development. The Biden administration has opposed the waiver but now has begun to signal at least tepid support.

Last Sunday, President Biden’s Chief Medical Adviser Anthony Fauci had warned that it was only a matter of time before the Omicron strain appeared in the U.S. He was proven right on Wednesday when California reported the first known case in a traveler from South Africa.

As the Delta surge showed over the summer of 2021, the vast swaths of the United States where vaccine rates are low are incredibly vulnerable to each new variant. After an initially impressive vaccine rollout, the U.S.’s vaccination rate has dropped off considerably. As of late October, the United States had the lowest vaccination rates of G7 countries.

If there is one spot of good news here, it’s that the Biden administration has embraced strong vaccination mandates, and the early data suggest that they’re working. In September, Biden issued an executive order requiring all federal workers to get the shot with exceptions in limited circumstances. As of November 23, 92 percent of the 3.5 million federal workers had gotten at least one shot, according to a White House fact sheet.

As part of that executive order, Biden also required all employees of companies with more than 100 workers to get vaccinated, obtain a waiver, or face weekly testing by early January. That order was challenged by at least 27 states in various districts and was subsequently blocked by a federal appeals court. A federal judge also blocked a Biden order mandating that health care workers get the vaccine, after 10 states sued.

Still, the company 3M (the largest producer of N95 masks in the U.S.) mandated that its employees get vaccinated in response to Biden’s executive order on federal workers. More broadly, Biden’s appeal to corporate behemoths to adopt vaccine mandates has seen some key success, as Procter & Gamble, Tyson Foods, and several airlines have required their workers to get the shot.

Although national hard data is difficult to pin down, anecdotally, at least many vaccine-hesitant people have preferred to get the vaccine rather than face the prospect of losing their jobs. State and municipal mandates have been incredibly successful as well. In New York State, a mandate for health care workers saw the number of people covered jump about 10 percent — from 82 to 92 percent — in the week before the requirement took hold. Even cops, who are part of one of the most reactionary and anti-vaccine professions in the country, have largely acquiesced to the requirement, even as their police associations have challenged the mandates in court.

The response from the right to the mandates — either those issued by Biden or by Democratic-controlled cities and states — has been predictable. Mississippi Gov. Tate Reeves said Biden’s federal mandates were something out of “communist China or North Korea.” A Fox News weekend host said they were the “beginning of a communist-style social credit system.” Right-wing website Red State referred to Biden’s speech as “dictatorial,” and conservative commentator Ben Shapiro said it was an example of the “authoritarianism” of the “administrative state.” After the conservative television station Newsmax announced it would enforce its own mandate, host Steve Cortes tweeted that he would not comply with “any organization’s attempt to enforce Biden’s capricious & unscientific Medical Apartheid mandate.”

In the months since Biden issued his federal mandate, the reactionary backlash hasn’t subsided, exactly, but conservatives have found other boogiemen to chase. Most notably, they rallied in a panic against in-school discussions of racism and oppression (which they inaccurately describe as “critical race theory”) in the Virginia gubernatorial race. Republicans have attacked Biden’s Build Back Better social spending plan as a reckless expansion of the welfare state. Rep. Lauren Boebert called Rep. Ilhan Omar a terrorist, then refused to publicly apologize. In short, conservatives are doing what they always do, and what they would have done had Biden not issued his executive orders on vaccine requirements.

The clear lesson for Democrats here is that cowering in anticipation of a backlash is morally indefensible in addition to being political malpractice. The constant media refrain in the run-up to the Virginia election was that the Democrats hadn’t done enough with their power, or, in Beltway-speak, they didn’t have “wins” to bring home. Poll after poll shows that Biden’s political future relies on increasing vaccination rates, stemming future waves and inching the country closer to an end-state where COVID is more like the seasonal flu and less like a life-altering pandemic.

Biden, and Democrats more broadly, will obviously get zero help from conservatives in this endeavor. Not only have the vast majority of Republican-controlled states resisted mask and vaccine mandates, but the GOP response to the Omicron variant has been even more mired in lies and conspiracy theories. Texas Republican and former Trump White House physician Ronny Jackson suggested the new variant had been invented by Democrats to justify mail-in voting in next year’s midterms. Similarly, Fox News hosts Will Cain and Pete Hegseth half-joked that the Biden administration would invent new variants “every two years” for their political benefit.

In retrospect, it’s now clear that Biden waited far too long to initiate federal vaccine mandates, almost entirely because his administration was afraid of the backlash they might generate. According to vaccine expert Peter Hotez, 150,000 people in the United States have died of COVID since June, when vaccines became widely available for Americans over 18. At least some of those people could have been saved — in some cases, in spite of their own instincts — had Biden pressed for large-scale mandates earlier.

There’s a rough analogy to be made here to another subject Democrats have waffled on for years for fear of sparking a backlash, specifically health care costs. There’s no question that much of the Democratic Party’s opposition to single-payer health care — or even a public option — is due to a genuine commitment to a privatized market, both ideologically and for the material benefit they get from health care sector lobbying. But the way that that commitment is often sold to liberal voters is that moving to a single-payer system would result in cries of authoritarianism and Stalinism from the right. As the left flank of the party has said for years, conservatives will accuse liberals of being socialists no matter what they do, so why not enact good policies and deal with the inevitable backlash when it comes.

More broadly, Democrats have imposed strict limits on themselves so as not to trigger blowback from Republicans for exercising their power when they have it. This manifests in all sorts of ways — from the Obama administration settling on a stimulus that some advisers knew was too small at the outset of the great recession, to the continuing reluctance from the party’s conservative wing to abolish the filibuster (even as a limited carve-out for voting rights). The Biden administration has been dragging its feet on negotiating lower drug costs, preferring to leave it to Congress despite the fact that there is executive action Biden could take in the meantime. Activists have also argued that Biden has the legal authority to cancel student debt without going through Congress, an action the administration seems to have placed in a state of permanent review. Some experts believe Biden has the statutory authority to make college essentially free by forgiving “loans equal to average public-college tuition on a rolling basis for two- and four-year public colleges.”

Every single one of these actions — not to mention any legislation Biden signs into law with only Democratic support — will generate massive backlash from conservatives. But so did federal, state and municipal vaccine mandates. Both morally and politically, the danger Democrats face is doing too little, losing power and being called authoritarians anyway.

This post was originally published on Latest – Truthout.

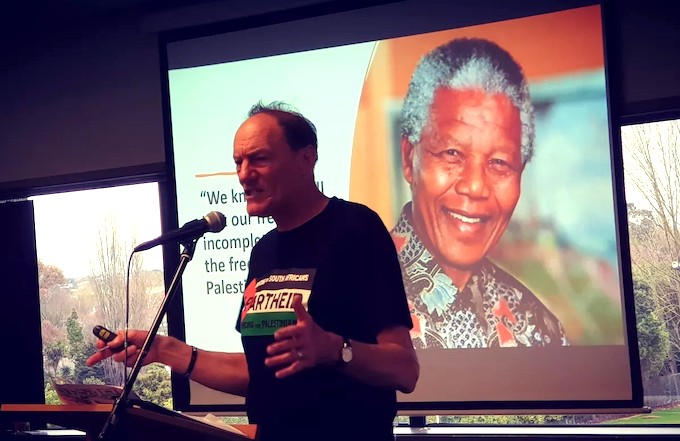

BREAKING: We are outside the embassies of the US & EU countries in Pretoria with a clear message: take real leadership and stop stonewalling the

BREAKING: We are outside the embassies of the US & EU countries in Pretoria with a clear message: take real leadership and stop stonewalling the