by James Bandler

ProPublica is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up to receive our biggest stories as soon as they’re published.

In early February 2016, the security gate at a U.S. military base near Washington, D.C., swung open to admit a Navy doctor accompanying a pair of surprising visitors: two artificial intelligence scientists from Google.

In a cavernous, temperature-controlled warehouse at the Joint Pathology Center, they stood amid stacks holding the crown jewels of the center’s collection: tens of millions of pathology slides containing slivers of skin, tumor biopsies and slices of organs from armed service members and veterans.

Standing with their Navy sponsor behind them, the Google scientists posed for a photograph, beaming.

Mostly unknown to the public, the trove and the staff who study it have long been regarded in pathology circles as vital national resources: Scientists used a dead soldier’s specimen that was archived here to perform the first genetic sequencing of the 1918 Flu.

Google had a confidential plan to turn the collection of slides into an immense archive that — with the help of the company’s burgeoning, and potentially profitable, AI business — could help create tools to aid the diagnosis and treatment of cancer and other diseases. And it would seek first, exclusive dibs to do so.

“The chief concern,” Google’s liaison in the military warned the leaders of the repository, “is keeping this out of the press.”

More than six years later, Google is still laboring to turn this vast collection of human specimens into digital gold.

At least a dozen Defense Department staff members have raised ethical or legal concerns about Google’s quest for service members’ medical data and about the behavior of its military supporters, records reviewed by ProPublica show. Underlying their complaints are concerns about privacy, favoritism and the private use of a sensitive government resource in a time when AI in health care shows both great promise and risk. And some of them worried that Google was upending the center’s own pilot project to digitize its collection for future AI use.

Pathology experts familiar with the collection say the center’s leaders have good reason to be cautious about partnerships with AI companies. “Well designed, correctly validated and ethically implemented [health algorithms] could be game-changing things,” said Dr. Monica E de Baca, chair of the College of American Pathologists’ Council on Informatics and Pathology Innovation. “But until we figure out how to do that well, I’m worried that –knowingly or unknowingly –there will be an awful lot of snake oil sold.”

When it wasn’t chosen to take part in JPC’s pilot project, Google pulled levers in the upper reaches of the Pentagon and in Congress. This year, after lobbying by Google, staff on the House Armed Services Committee quietly inserted language into a report accompanying the Defense Authorization Act that raises doubts about the pathology center’s modernization efforts while providing a path for the tech giant to land future AI work with the center.

Pathology experts call the JPC collection a national treasure, unique in its age, size and breadth. The archive holds more than 31 million blocks of human tissue and 55 million slides. More recent specimens are linked with detailed patient information, including pathologist annotations and case histories. And the repository holds many examples of “edge cases” — diseases so vanishingly rare that many pathologists never see them.

Human tissue samples from 1917 and 1918 stored in paraffin are part of the Joint Pathology Center’s collection, which contains more than 31 million tissue blocks and 55 million slides.

(Linda Davidson/The Washington Post via Getty Images)

Google sought to gather so many identifying details about the specimens and patients that the repository’s leaders feared it would compromise patients’ anonymity. Discussions became so contentious in 2017 that the leaders of the JPC broke them off.

In an interview with ProPublica, retired Col. Clayton Simon, the former director of the JPC, said Google wanted more than the pathology center felt it could provide. “Ultimately, even through negotiations, we were unable to find a pathway that we legally could do and ethically should do,” Simon said. “And the partnership dissolved.”

But Google didn’t give up. Last year, the center’s current director, Col. Joel Moncur, in response to questions from DOD lawyers, warned that the actions of Google’s chief research partner in the military “could cause a breach of patient privacy and could lead to a scandal that adversely affects the military.”

Joel Moncur

(Kate Copeland for ProPublica)

Google has told the military that the JPC collection holds the “raw materials” for the most significant biotechnology breakthroughs of this decade — “on par with the Human Genome Project in its potential for strategic, clinical, and economic impact.”

All of that made the cache an alluring target for any company hoping to develop health care algorithms. Enormous quantities of medical data are needed to design algorithmic models that can identify patterns a pathologist might miss — and Google and other companies are in a race to gather them. Only a handful of tech companies have the scale to scan, store and analyze a collection of this magnitude on their own. Companies that have submitted plans to compete for aspects of the center’s modernization project include Amazon Web Services, Cerner Corp. and a host of small AI companies.

But no company has been as aggressive as Google, whose parent company, Alphabet, has previously drawn fire for its efforts to gather and crunch medical data. In the United Kingdom, regulators reprimanded a hospital in 2017 for providing data on more than 1.6 million patients, without their understanding, to Alphabet’s AI unit, DeepMind. In 2019, The Wall Street Journal reported that Google had a secret deal, dubbed “Project Nightingale,” with a Catholic health care system that gave it access to data on millions of patients in 21 states, also without the knowledge of patients or doctors. Google responded to the Journal story in a blog post that stated that patient data “cannot and will not be combined with any Google consumer data.”

In a statement, Ted Ladd, a Google spokesperson, attributed the ethics complaints associated with its efforts to work with the repository to an “inter-agency issue” and a “personnel dispute.”

“We had hoped to enable the JPC to digitize its data and, with its permission, develop computer models that would enable researchers and clinicians to improve diagnosis for cancers and other illnesses,” Ladd said, noting that all of Google’s health care partnerships involve “the strictest controls” over data. “Our customers own and manage their data, and we cannot — and do not — use it for any purpose other than explicitly agreed upon by the customer,” Ladd said.

In response to questions from ProPublica, the JPC said none of its de-identified data would be shared during its modernization process unless it met the ethical, regulatory, and legal approvals needed to ensure it was done in the right way.

“The highest priority of the JPC’s digital transformation is to ensure that any de-identified digital slides are used ethically and in a manner that protects patient privacy and military security,” the JPC said.

But some fear that even these safeguards might not be enough. Steven French, a DOD cloud computing engineer assigned to the project, said he was dismayed by the relentlessness of Google’s advocates in the department. Lost in all their discussions about the speed, scale and cost-saving benefits associated with working with Google seemed to be concerns for the interests of the service members whose tissue was the subject of all this maneuvering, French told ProPublica.

“It felt really bad to me,” French said. “Like a slow crush towards the inevitability of some big tech company monetizing it.”

The JPC certainly does need help from tech companies. Underfunded by Congress and long neglected by the Pentagon, it is vulnerable to offers from well-funded rescuers. In spite of its leaders’ pleas, funding for a full-scale modernization project has never materialized. The pathology center’s aging warehouses have been afflicted with water leaks and unwelcome intruders: a marauding family of raccoons.

The story of the pathology center’s long, contentious battle with Google has never been told before. ProPublica’s account is based on internal emails, presentations and memos, as well as interviews with current and former DOD officials, some of whom asked not to be identified because they were not authorized to discuss the matter or for fear of retribution.

Google’s Private Tour

In December 2015, Google began its courtship of the JPC with a bold, unsolicited proposal. The messenger was a junior naval officer, Lt. Cmdr. Niels Olson.

“I’m working with Google on a project to apply machine learning to medical imaging,” Olson wrote to the leaders of the repository. “And it seems like we are at the stage where we need to figure exactly what JPC has.”

Niels Olson

(Kate Copeland for ProPublica)

A United States Naval Academy physics major and Tulane medical school graduate, Olson worked as a clinical and anatomical pathology resident at the Naval Medical Center in San Diego.

With digitized specimen slides holding massive amounts of data, pathology seemed ripe for the coming AI revolution in medicine, he believed. Olson’s own urgency was heightened in 2014 when his father was diagnosed with prostate cancer.

That year, Olson teamed up with scientists at Google to train software to recognize suspected cancer cells. Google supplied expertise including AI scientists and high-speed, high-resolution scanners. The endeavor had cleared all privacy and review board hurdles. They were scanning Navy patients’ pathology slides at a furious clip, but they needed a larger data set to validate their findings.

Enter the JPC’s archive. Olson learned about the center in medical school. In his email to its leaders in December 2015, Olson attached Google’s eight-page proposal.

Google offered to start the operation by training algorithms with already digitized data in the repository. And it would do this early work “with no exchange of funds.” These types of partnerships free the private parties from having to undergo a competitive bidding process.

Google promised to do the work in a manner that balanced “privacy and ethical considerations.” The government, under the proposal, would own and control the slides and data.

Olson typed a warning: “This is under a non-disclosure agreement with Google, so I need to ask you, do please handle this information appropriately. The chief concern is keeping this out of the press.”

Senior military and civilian staff at the pathology center reacted with alarm. Dr. Francisco Rentas, the head of the archive’s tissue operations, pushed back against the notion of sharing the data with Google.

“As you know, we have the largest pathology repository in the world and a lot of entities will love to get their hands on it, including Google competitors. How do we overcome that?” Rentas asked in an email.

Olson, center, and Google scientists Martin Stumpe and Lily Peng took a private tour of the JPC collection in 2016.

(Obtained by ProPublica)

Other leaders had similar reactions. “My concerns are raised when I’m advised to not disclose what seems to be a contractual relationship to the press,” one of the top managers at the pathology center, Col. Edward Stevens, told Olson. Stevens told Olson that giving Google access to this information without a competitive bid could result in litigation from the company’s competitors. Stevens asked: “Does this need to go through an open-source bid?”

But even with these concerns, Simon, the pathology center’s director, was intrigued enough to continue discussions. He invited Olson and Google to inspect the facility.

The warehouse Olson and the Google scientists entered could have served as a set for the final scene of “Raiders of Lost Ark.”

Pathology slides were stacked in aisle canyons, some towering two stories. The slides were arranged in metal trays and cardboard boxes. To access tissue samples, the repository used a retrieval system similar to those found in dry cleaners. The pathology center had just a handful of working scanners. At the pace they were going, it would take centuries to digitize the entire collection.

One person familiar with the repository likened it to the Library of Alexandria, which held the largest archive of knowledge in the ancient world. Myth held that the library was destroyed in a cataclysmic fire lit by Roman invaders, but historians believe the real killer was gradual decay and neglect over centuries.

The JPC’s collection is the largest biorepository on the planet.

(Linda Davidson/The Washington Post via Getty Images)

The military’s tissue library had already played an important role in the advancement of medical knowledge. Its birth in 1862 as the Army Medical Museum was grisly. In a blandly written order in the midst of the Civil War, the Army surgeon general instructed surgeons “diligently to collect and preserve” all specimens of “morbid anatomy, surgical or medical, which may be regarded as valuable.”

Soon the museum’s curator was digging through battlefield trenches to find “many a putrid heap” of hands, feet and other body parts ravaged by disease and war. He and other doctors shipped the remains to Washington in whiskey-filled casks.

Over the next 160 years, the tissue collection outgrew several headquarters, including Washington’s Ford Theater and a nuclear-bomb-proof building near the White House. But the main mission — identifying, studying and reducing the calamitous impact of illnesses and injuries afflicting service members — has remained unchanged in times of war and peace. Each time a military or veterans’ hospital pathologist sent a tissue sample to the pathology center for a second opinion, it was filed away in the repository.

As the archive expanded, the repository’s prestige grew. Its scientists spurred advances in microscopy, cancer and tropical disease research. An institute pathologist named Walter Reed proved that mosquitoes transmit yellow fever, an important discovery in the history of medicine.

For much of its modern history, in addition to serving military and veterans hospitals, the center also provided civilian consultations. The work with elite teaching hospitals gave the center a luster that helped it attract and retain top pathologists.

Congress and DOD leaders questioned why the military should fund civilian work that could be done elsewhere. In 2005, under the congressionally mandated base closure act, the Pentagon ordered the organization running the repository to shut down. The organization reopened with a different overseer, tasked with a narrower, military-focused mission. Uncertainty about the organization’s future caused many top pathologists to leave.

In its first pitch to the repository’s leaders, Google pointedly mentioned a book-length Institute of Medicine report on the repository that stated that “wide access” to the archive’s materials would promote the “public good.” The biorepository wasn’t living up to its potential, Google said, noting that “no major efforts have been underway to fix the problem.”

Following the tour, a Google scientist prepared a list of clinical, demographic and patient information it sought from the repository. The list included “must haves” — case diagnoses; pathology and radiology images; information on gender and ethnicity; and birth and death dates — as well as “high-value” patient information, including comorbidities, subsequent hospitalizations and cause of death.

This troubled the JPC’s director. “We felt very, very concerned about giving too much data to them,” Simon told ProPublica, “because too much data could identify the patient.”

There were other aspects about Google’s offer that made it “very unfavorable to the federal government,” Simon later told his successor, according to an email reviewed by ProPublica.

In exchange for scanning and digitizing the slide collection at its own expense, Google sought “exclusive access” to the data for at least four years.

The other deal-breaker was Google’s requirement that it be able to charge the government to store and access the digitized information, a huge financial commitment. Simon did not have the authority to commit the government to future payments to a company without authorization from Congress.

Today, Ladd, the Google spokesperson, disputes the claim that its proposal would have been unfavorable to the government. “Our goal was to help the government digitize the data before it physically deteriorates.”

Ladd said Google sought exclusive access to the data during the early stages of the project, so that it could scan the de-identified samples and perform quality-control measures on the data prior to handing it back to the JPC.

Niels Olson, who spearheaded the project for the Navy in 2016, declined requests for interviews with ProPublica. But Jackson Stephens, a friend and lawyer who is representing Olson, said Olson had always followed the Institutional Review Board process and worked to anonymize patient medical data before it was used in research or shared with a third party.

“Niels takes his oath to the Constitution and his Hippocratic oath very seriously,” Stephens said. “He loves science, but his first duty of care is to his patients.”

Google’s relentlessness in 2017, too, spooked the repository’s leaders, according to an email reviewed by ProPublica. Google’s lawyer put “pressure” on the head of tissue operations to sign the agreement, which he declined to do. Leaders of the center became “uncomfortable” and discontinued discussions, according to the DOD email.

Though he banged on doors in the Pentagon and Congress, Simon was not able to convince the Obama administration to include the JPC in then-Vice President Joe Biden’s Cancer Moonshot. Simon left the JPC in 2018, his hopes for a modernization of the library dashed. But then a Pentagon advisory board got wind of the JPC collection, and everything changed.

“The Smartest People on Earth”

In March of 2020, the Defense Innovation Board announced a series of recommendations to digitize the JPC collection. The board called for a pilot project to scan a large initial batch of slides — at least 1 million in the first year — as a prelude to the massive undertaking of digitizing all 55 million slides.

“My worldview was that this should be one of the highest priorities of the Defense Department,” William Bushman, then acting deputy undersecretary of personnel and readiness, told ProPublica. “It has the potential to save more lives than anything else being done in the department.”

As the pathology center prepared to launch its pilot, the staff talked about a scandal that occurred just 40 miles north.

Henrietta Lacks was a Black woman who died of cancer in 1951 while being treated at Baltimore’s Johns Hopkins Hospital. Without her or her family’s knowledge or consent, and without compensation, her cells were replicated and commercialized, leading to groundbreaking advances in medicine but also federal reforms on the use of patient cells for research.

A photo of Henrietta Lacks sits in the living room of her grandson, Ron Lacks.

(Jonathan Newton/The Washington Post via Getty Images)

Like Lacks’ cancer cells, every specimen in the archive, the JPC team knew, represented its own story of human mortality and vulnerability. The tissue came from veterans and current service members willing to put their lives on the line for their country. Most of the samples came from patients whose doctors discovered ominous signs from biopsies and then sent the specimens to the center for second opinions. Few signed consent forms agreeing to have their samples used in medical research.

The pathology center hired two experts in AI ethics to develop ethical, legal and regulatory guidelines. Meanwhile, the pressure to cooperate with Google hadn’t gone away.

In the summer of 2020, as COVID-19 surged across the country, Olson was stationed at a naval lab in Guam, working on an AI project to detect the coronavirus. That project was managed by a military group based out of Silicon Valley known as the Defense Innovation Unit, a separate effort to speed the military’s development and adoption of cutting-edge technology. Though the group worked with many tech companies, it had gained a reputation for being cozy with Google. The DIU’s headquarters in Mountain View, California, sat just across the street from the Googleplex, the tech giant’s headquarters. Olson joined the group officially that August.

Olson’s COVID-19 work earned him Navy Times’ coveted Sailor of the Year award as well as the attention of a man who would become a powerful ally in the DOD, Thomas “Pat” Flanders.

Flanders was the chief information officer of the sprawling Defense Health Agency, which oversaw the military’s medical services, including hospitals and clinics. A garrulous Army veteran, Flanders questioned the wisdom of running the pilot project without first getting funding to scan all of the 55 million slides. He wanted the pathology staff to hear about the work Olson and Google had done scanning pathology slides in San Diego and see if a similar public-private partnership could be forged with the JPC.

Over the objections of Moncur, the JPC’s director, Flanders insisted on having Olson attend all the pathology center’s meetings to discuss the pilot, according to internal emails.

In August 2020, the JPC published a request for information from vendors interested in taking part in the pilot project. The terms of that request specified that no feedback would be given to companies about their submissions and that telephone inquiries would not be accepted or acknowledged. Such conversations could be seen as favoritism and could lead to a protest by competitors who did not get this privilege.

But Flanders insisted that meeting Google was appropriate, according to Moncur’s statements to DOD lawyers.

In a video conference call, Flanders told the Google representatives they were “the smartest people on earth” and said he couldn’t believe he was “getting to meet them for free,” according to written accounts of the meeting provided to DOD lawyers.

Flanders asked Google to explain its business model, saying he wanted to see how both the government and company might profit from the center’s data so that he could influence the requirements on the government side — a remark that left even the Google representatives “speechless,” according to a compilation of concerns raised by DOD staffers.

To Moncur and others in attendance, Flanders was actively negotiating with Google, according to Moncur’s statement to DOD lawyers.

To the astonishment of the center staff, Flanders asked for a second meeting between Google and the JPC team.

Concern about Flanders’ conduct echoed in other parts of the DOD. A lawyer for Defense Digital Service, a team of software engineers, data scientists and product managers assigned to assist on the project, wrote that Flanders ignored legal warnings. He described Flanders as a “cowboy” who in spite of warnings about his behavior was not likely “to fall out of love with Google.”

In an interview with ProPublica, Flanders disputed claims that he was biased toward Google. Flanders said his focus has always been on scanning and storing the slides as quickly and economically as possible. As for his lavish praise of Google, Flanders said he was merely trying to be “kind” to the company’s representatives.

“People took offense to that,” Flanders said. “It’s just really pettiness on the part of people who couldn’t get along, honestly.”

A spokesperson for the Defense Health Agency said it was “totally appropriate” for Flanders to ask Google about its business model. “This is part of market research,” the spokesperson wrote, adding that no negotiation occurred at the meeting and that all government stakeholders had been invited to attend.

Moncur referred calls to a JPC spokesperson. A spokesperson for the JPC said in a statement that “Moncur was concerned about meeting with vendors during the RFI period.”

“An Arm of Google”

In late 2020, the modernization team received more troubling news. In a slide presentation for the JPC describing other AI work with Google and the military, Olson disclosed that the company had “made offers of employment, which I have declined.” But then he suggested the offer might be revived in the future, writing, “we mutually agreed to table the matter.” He said he had “no other conflicts of interest to declare.” Google told ProPublica it had never directly made Olson a job offer, though a temp agency it used did.

More facts surfaced. Olson also had a Google corporate email address. And he had access to Google corporate files, according to internal communications from concerned DOD staff members. Google said it is common for its research partners in the government to have these privileges.

“I am more worried than ever that DIU’s influence will destroy this acquisition,” a DOD lawyer wrote, referring to efforts to find vendors for the pilot project. He called DIU “essentially an arm of Google.”

At the time, a DIU lawyer defended Olson. The lawyer said Olson had “no further conflict of interest issues” and had done nothing improper because the job offer had been made three years earlier, in 2017. An ethics officer at the DOD Standards of Conduct Office agreed.

Today, a spokesperson in the Office of the Secretary of Defense told ProPublica the department was committed to modernizing the repository “while carefully observing all applicable legal and ethical rules.”

Olson’s friend and lawyer, Stephens, said Olson had been upfront, disclosing the job offer to the innovation unit’s lawyer as well as in the conflict-of-interest section of his slide presentation. He said Olson had declined the offer, which was withdrawn. “He’s not some kind of Google secret agent.”

Stephens said the JPC would have been much further down the road had it cooperated with Olson. Stephens said it became apparent to Olson that Moncur was “essentially ignoring” a “gold mine that could help a lot of people.”

“Niels is the tenacious doctor who is just trying to do the science and build a coalition of partners to get this thing done,” Stephens said. “I think he’s the hero of this story.”

Google Turns to Congress

In 2021, the pathology center selected one of the most prestigious medical institutions in the world, Johns Hopkins — which plans to erect a building honoring Henrietta Lacks — to assist it in scanning slides. It picked two small technology companies to start building tools to let pathologists search the archive.

Google wanted to be selected, and in a confidential proposal, it offered to help the repository build up its own slide-scanning capabilities.

When Google was not selected for the pilot project, the company went above the JPC leaders’ heads. Google claimed in a letter to Pentagon leaders that the company had been unfairly excluded from “full and open competition.” In that August 2021 letter, Google argued that the nation’s security was at stake. It asked the DOD to “consider allowing Google Cloud” and other providers to compete to ensure the “nation’s ability to compete with China in biotechnology.”

Time was of the essence, Google warned. “The physical slides at the JPC are degrading rapidly each day. … Without further action, the slides will continue to degrade and some may ultimately be damaged beyond repair.”

Google stepped up its advocacy campaign. The company deployed a lobbying firm, the Roosevelt Group — which boasts of its ability to “leverage” its connections to secure federal business opportunities to its clients — to raise doubts about the JPC’s pilot project. Their efforts worked. In little-noticed language in a report written to accompany the 2023 Defense Authorization Act, the House Armed Services Committee expressed its concern about the speed of the scanning process and the choice of technology, which the committee claimed would not allow the “swift digitization of these deteriorating slides.”

The committee had its own ideas of how the pathology center’s work should be carried out, suggesting that the center work in tandem with the DIU, using an augmented reality microscope whose software was engineered by Google.

In a statement, the Roosevelt Group told ProPublica it was “proud” of its work for Google. The firm said it helped the company “educate professional staff of the House and Senate Armed Services Committees over concerns about the lack of an open procurement process for digitization of slides.” The group chided DOD officials for being “unwilling to provide answers to Congress around the lack of progress on the JPC digitization effort.”

The pathology center staff was dismayed by the committee’s recommendations that it work with Olson’s group.

In a video conference meeting late last summer with Armed Services Committee staff, the leaders of the pathology center attempted to rebut the House committee report. The JPC’s work was going as planned, they said, noting that a million slides had been scanned. And the pathology center was collaborating with the National Institutes of Health to develop AI tools to help predict prognoses for cancer treatments.

The House Armed Services Committee ordered Pentagon leaders to “conduct a comprehensive assessment” on the digitization effort and to provide a briefing to the committee on its findings by April 1, 2023.

In a statement in response to ProPublica’s questions about the bill, Ladd, the Google spokesperson, acknowledged the company’s influence efforts on Capitol Hill. “We frequently provide information to congressional staff on issues of national importance,” Ladd said. The statement confirmed that the company suggested “language be inserted” into the 2023 Defense Authorization Act calling for a “comprehensive assessment” of the digitization effort.

“Despite efforts from Google and many at the Department of Defense, our work with JPC unfortunately never got off the ground, and the physical repository of pathology slides continues to deteriorate,” Ladd said. “We remain optimistic that if the repository could be properly digitized, it would save many American lives, including those of our service members.”

On this last point, even Google’s critics are in accord. A properly funded project would cost taxpayers a few hundred million dollars — a minuscule portion of the $858 billion defense budget and a small price if the lifesaving potential of the collection is realized.

Last year, as tensions grew with Google, the modernization team at the repository launched a publicity campaign to call attention to the project and the high ethical stakes.

An entire panel discussion was devoted to the JPC effort at the 2021 South by Southwest conference. “This is a once in a lifetime opportunity, and I want to make sure we do it right, we do it responsibly and we do it ethically,” said Steven French, the DOD cloud computing engineer assigned to assist the repository.

Then without mentioning Google’s name, he added a Shakespearean barb. “There’s plenty of vendors, plenty of companies, plenty of people,” French said, “who are more than willing to do this and extract a pound of flesh from us in the process.”

Additional image credits: Duncan1890, Cultura RM Exclusive/PhotoStock-Israel, Rob Jones III, Kampee Patisena, Steve Gschmeissner/Science Photo Library, Sebastian Condrea, Jason Edwards, undefined undefined, Mikroman6, Trifonov_Evgeniy, Zoranm, Wladimir Bulgar/Science Photo Library, Michael Burrell, DanielBendjy, John Parrot/Stocktrek Images, PansLaos, SDI Productions, George Marks, Carlofranco, Tetra Images, Leonello Calvetti/Science Photo Library, Mashuk, and Thepalmer/Getty Images

Doris Burke contributed research.

This post was originally published on Articles and Investigations – ProPublica.

New Culture

New Culture

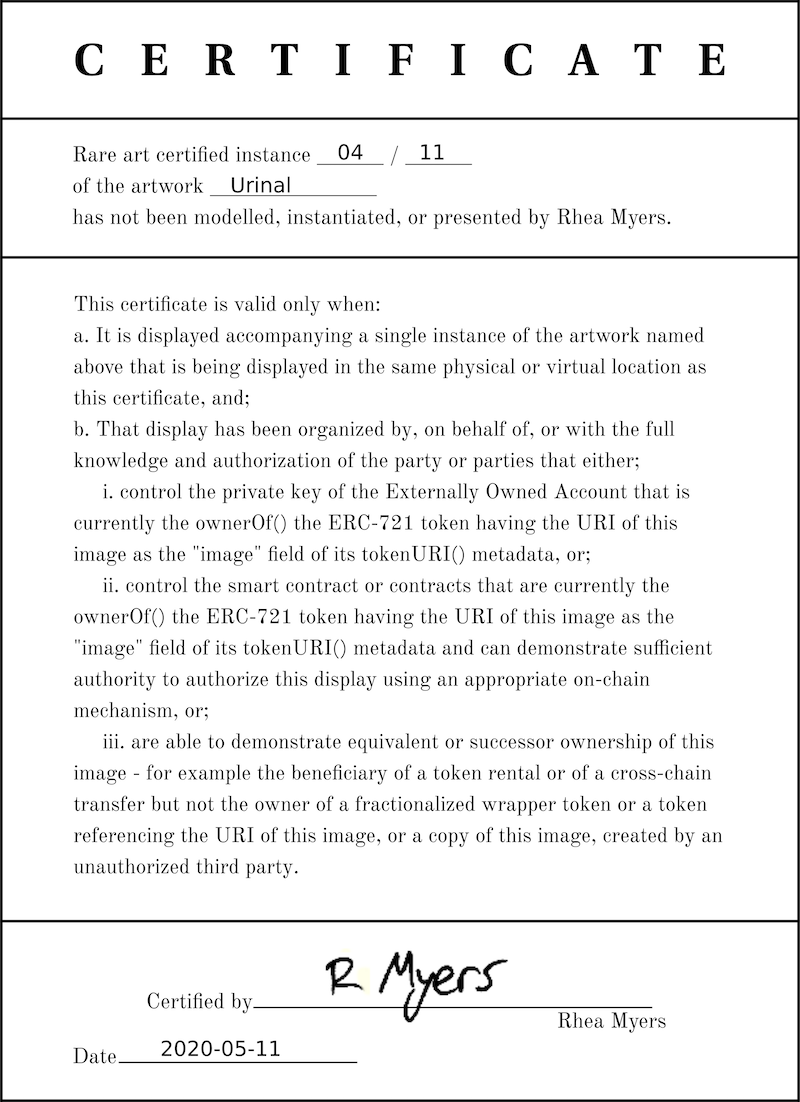

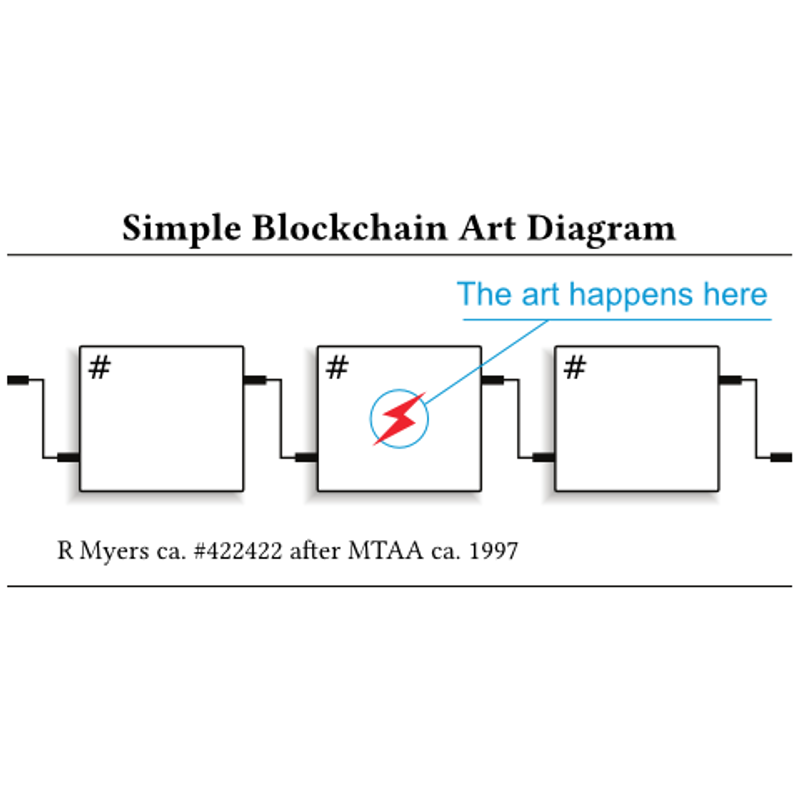

Tokens Equal Text, 2019, Ethereum ERC-998 and ERC-721 tokens

Tokens Equal Text, 2019, Ethereum ERC-998 and ERC-721 tokens