by Peter Elkind

ProPublica is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up to receive our biggest stories as soon as they’re published.

The prospect sounded terrifying. A nationwide rollout of new wireless technology was set for January, but the aviation industry was warning it would cause mass calamity: 5G signals over new C-band networks could interfere with aircraft safety equipment, causing jetliners to tumble from the sky or speed off the end of runways. Aviation experts warned of “catastrophic failures leading to multiple fatalities.”

To stave off potential disaster, the Federal Aviation Administration prepared drastic preventive measures that would cancel thousands of flights, stranding passengers from coast to coast and grounding cargo shipments. “The nation’s commerce will grind to a halt,” the airlines’ trade group predicted.

On Jan. 18, following nail-biting negotiations involving CEOs, a Cabinet secretary and White House aides, an eleventh-hour agreement averted these threats of aviation armageddon. Verizon and AT&T agreed not to turn on more than 600 5G transmission towers near the runways of 87 airports and to reduce the power of others.

Disaster was averted. But the fact that it was such a close call was shocking nonetheless. How did a long-planned technology upgrade result in a standoff that seemed to threaten public safety and one of the nation’s largest industries? The reasons are numerous, but it’s undeniable that the new 5G deployment represents an epic debacle by multiple federal agencies, the regulatory equivalent of a series of 300-pound football players awkwardly fumbling the ball as it bounces crazily into and out of their arms.

More than anything, a deep examination of the fiasco reveals profound failures in two federal agencies — the Federal Communications Commission and the FAA — that are supposed to serve the public. In the case of the FCC, the agency not only advocated for the interests of the telecommunications industry but adopted its worldview, scorning evidence of risk and making cooperation and compromise nearly impossible. In the case of the FAA, the agency inexplicably stayed silent and passively watched preparations for 5G proceed over a period of years even as the aviation industry sounded ever more dire warnings that the new networks could put air safety at risk.

That’s the alarming picture that emerges, in new detail, in interviews with 51 participants and observers in the 5G rollout, along with a review of thousands of pages of documents. The problems have spanned a Republican and Democratic administration. The process first ran off the rails under President Donald Trump. It then festered under the administration of President Joe Biden — which ProPublica’s reporting shows impeded the FAA when it finally decided to act — until a crisis forced an intervention.

For now, the truce between the FCC and telecom companies, on one side, and the FAA and aviation companies, on the other, is holding. The parties have mostly tempered their hostile rhetoric, sounded hopeful notes of “coexistence” and have begun to collaborate. The FAA is allowing the wireless companies to slowly turn on more 5G towers as planes mostly keep flying. (About a thousand regional jets, mostly used by JetBlue, American, Delta and United, are currently barred from landing in low-visibility conditions at many airports over fears of equipment interference.)

But the underlying issues are far from resolved. Aviation companies say they need much more time — perhaps two years or more — to upgrade or replace all the equipment vulnerable to 5G interference, according to Bob Fox, a United Airlines pilot now serving as national safety coordinator for the Air Line Pilots Association, a key player in the drama.

The telecom companies have no interest in such a lengthy time frame: Their agreement with the government is set to expire on July 5, and they have made no commitment to extending the restrictions on their towers past that date. The companies have been exhibiting a willingness to make short-term compromises, but they’re also showing hints of frustration that they can’t seem to bring the process to a resolution.

For its part, the FCC seems aggrieved. It overwhelmingly blames the aviation agency for the problems and simultaneously says it’s cooperating with the FAA — while continuing to insist that any claims that 5G will threaten airplanes are pure fantasy. The rhetoric of the FCC chief is almost identical to that of the industry she regulates. As recently as last month, Jessica Rosenworcel, the Biden-appointed FCC chair, dismissed aviation concerns as, in effect, a shakedown — a ploy to get telecom companies to fund a nationwide upgrade of airplane equipment. Referring to the air-safety devices that the aviation industry says could be compromised by 5G, she said in an interview with ProPublica, “Has anyone spec’d the cost of altimeter replacement?”

And a whole new telecom-aviation conflict could soon emerge. T-Mobile and other wireless companies are approved to roll out additional 5G service at the end of 2023, using a C-band frequency even closer to the one used by the airplane safety equipment. Like other participants in the process, T-Mobile says it’s committed to safety and to finding a reasonable solution. But if that rollout unfolds in a way that resembles the last one in the slightest way, a reasonable solution may be elusive.

There was a time, a century ago, when radio was the hottest new technology in the land. Stations sprouted up everywhere, and they routinely used the same frequencies. The result was electronic bedlam: Programming was regularly interrupted by rival stations, police-radio chatter and amateur enthusiasts. Congressional legislation lamented “the present chaos of jazz bands, sermons, crop reports, sporting services, concerts and whatnot running simultaneously on the same wave lengths.” In one celebrated case, a wealthy Illinois bank president obtained a court order against a local 18-year-old whose radio transmissions had kept him from listening to broadcasts of election-night results at his home.

Since its founding in 1934, the Federal Communications Commission has decided which companies would have rights to which parts of the airwaves — for television and countless other technologies. Here, an RCA engineer examines an array of ultrahigh-frequency TV antennas in 1952.

(Bettmann Archive/Getty Images)

There was a critical need for a neutral arbiter to make decisions about who could occupy which part of the airwaves. All this led to the creation of a federal agency to regulate radio, which ultimately morphed into the FCC in 1934. A big part of its mission, as the new agency told Congress, was to make “equitable distribution of the frequencies … as congestion increases.”

The march of technology over the 88 years that followed can be understood as a series of battles for the airwaves. Virtually every important communications technology, from television and satellites to cellphones and GPS, has required bandwidth. The FCC was there to dole out frequencies and referee the conflicts. There were massive financial stakes in many of the decisions. They launched entire industries, while burying or transforming others.

As more and more technologies crowded into a finite set of frequencies, the opportunities for one technology to interfere with another only increased. In the mid-1990s, new digital phone technology unintentionally triggered a buzzing in some hearing aids, while interference from police radios sometimes prompted powered wheelchairs to randomly accelerate or brake, leading to serious injuries. In 2010, the shift to digital television required the replacement of wireless microphones used by actors in Broadway shows, referees at NFL games and pastors at Sunday church services.

By the time 5G approached, the FCC had long ago developed an acclaimed system of selling spectrum — reserved areas of the airwaves — for commercial use, which generated large sums of money for the federal government: public auctions. The agency’s first such auction was held in 1994. Over the years that followed, the FCC successfully used the process 110 times, raising more than $233 billion. The auctions’ sophisticated format helped win a Nobel Prize for two Stanford economists who designed them.

But the Trump administration didn’t initially seem inclined to leave 5G decisions to the FCC. The administration saw the fifth generation of cellular technology, with its faster speeds and automation efficiencies for industry, as its single biggest communications initiative.

Top Trump officials viewed the technology through the prism of competition with China. Many in the administration also expressed fears that Huawei Technologies, a dominant maker of 5G hardware, might be a conduit for Chinese government surveillance, posing a national-security threat. (Huawei has always denied such claims.) Trump lieutenants began employing a nationalist battle cry: America needed to “win the race to 5G” against China.

The Trump administration veered in multiple directions in pursuit of that goal. In January 2018, National Security Council officials circulated a plan to create a government-run 5G network. This idea was jettisoned almost as soon as it was proposed, amid criticism that this would constitute socialism.

President Donald Trump, with AT&T’s then-CEO, Randall Stephenson, in 2017, examining a model of how 5G will be deployed in cities. Trump was a cheerleader for 5G adoption but often cast the process as part of a race against China.

(Olivier Douliery-Pool/Getty Images)

Others in the Trump orbit proposed ideas as well. Attorney General William Barr at one point suggested that the U.S. government, in the interest of developing China-free 5G networks, buy controlling interests in Nokia and Ericsson, the European telecom equipment companies. Republican insiders such as consultant Karl Rove, former House Speaker Newt Gingrich and Trump campaign manager Brad Parscale promoted a partnership in which the Defense Department would lease unused spectrum to Rivada Networks, a company backed by GOP donor Peter Thiel. This approach was embraced by a Trump campaign spokesperson and then promptly repudiated by the White House. Trump himself declared that the administration’s 5G plan should be “private-sector driven and private-sector led.”

Eventually the White House moved on to other obsessions. The FCC, and its chairman, became the driving force in the race to 5G. The agency’s brash leader, 44 when he took the role in 2017, was Ajit Pai. He had been an FCC commissioner before being elevated by Trump. Pai’s agency was legendarily friendly to the companies it regulated, with commissioners and key staff routinely moving to and from lucrative posts in the industry. Pai himself had spent two years early in his career as an in-house lawyer at Verizon and later worked at a law firm that served telecom clients. Since stepping down at the end of the Trump administration, Pai has decamped to a private-equity firm whose portfolio includes telecom and broadband companies.

At the FCC, Pai joined the wireless companies in evangelizing for 5G. He would make it the central initiative of his tenure. A speedy rollout, Pai proclaimed, would “transform our economy, boost economic growth and improve our quality of life.” He regularly cited a report proclaiming that 5G could create up to 3 million new U.S. jobs and $500 billion in economic growth — without noting that those rosy figures came from a study commissioned by the wireless industry’s lobbying group.

Under Pai, the path to 5G initially continued to zigzag. After the White House abandoned the central plan, the FCC turned in a new direction, one that would put a few foreign satellite companies in charge of the process. At issue was the so-called C-band, a patch of wireless real estate viewed as the sweet spot for 5G. Wireless companies coveted C-band spectrum for its ability to transmit big chunks of data rapidly over long distances; it would maximize 5G speeds while minimizing the number of expensive cell towers and transmitters the companies needed.

That spectrum was owned by the federal government. But it was then being used with the government’s consent, free of charge, by four foreign satellite companies that relayed radio and TV signals around the globe. Sensing opportunity, the companies banded together and made an audacious proposal: They, the non-rent-paying users of the spectrum, would sell it to U.S. wireless companies and keep most of the expected tens of billions of dollars for themselves. (They agreed to make a voluntary contribution to the federal Treasury from the proceeds.) This “market-based solution,” the satellite companies claimed, would be the fastest way to get 5G networks up and running.

Pai seriously entertained this approach for a year. The plan eventually fizzled in the face of fierce opposition led by Louisiana Republican Sen. John Kennedy, who expressed outrage that foreign satellite companies would reap most of the money from a sale of U.S. government spectrum.

FCC Chairman Ajit Pai, shown in 2017, was an evangelist for 5G. He regularly cited a report proclaiming that the technology could create up to 3 million jobs, without noting that those figures came from a study commissioned by the wireless industry’s lobbying group.

(Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

Stymied, the FCC swerved back to its traditional approach: a public spectrum auction, in this case for a big chunk of the C-band. The agency decided that the winning bidders would pay the satellite companies up to $14.7 billion for quickly vacating those frequencies and retooling on different frequencies. That, the agency hoped, would avoid costly, time-consuming lawsuits by the satellite companies.

A $14.7 billion payout was staggering, but it was an accepted FCC practice to arrange compensation for companies affected by its spectrum actions. The agency, however, would make no such provisions for another group warning of far graver consequences: the U.S. aviation industry.

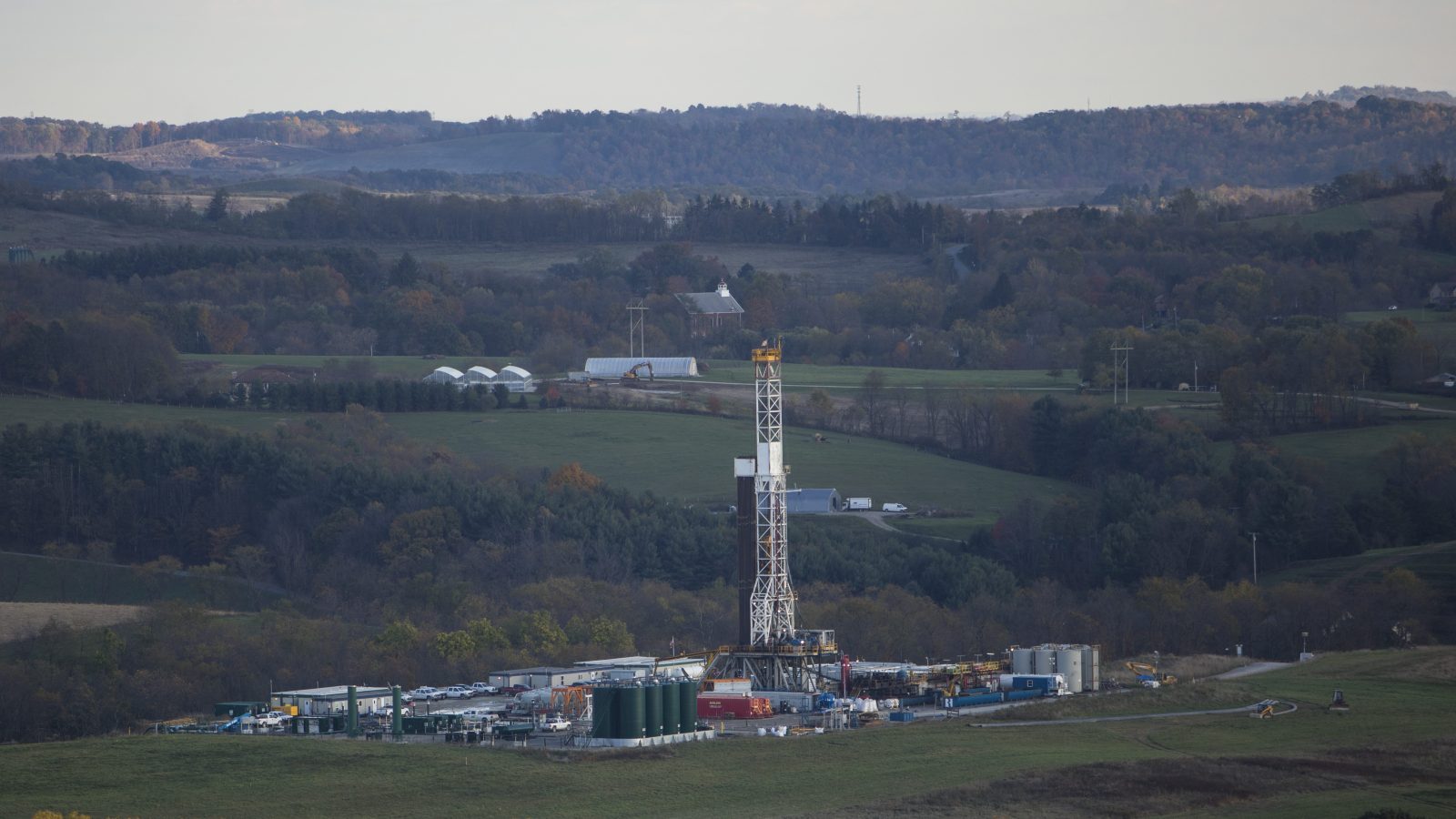

The battle that would threaten to ground American aviation centered on an electronic device about the size of a toaster. Called a radio altimeter, it’s used to track an aircraft’s altitude during takeoff and landing.

Radio altimeters, which became standard gear in the early 1970s, work by bouncing an electronic signal off the ground, sending their readings instantly to the cockpit. This is important for low-visibility landings, at night or in bad weather. It matters at other times, too: Radio altimeters on many commercial jets feed their data into automated navigation and crash-avoidance systems, sometimes controlling the engines and braking systems. About 50,000 planes and helicopters in the U.S. carry radio altimeters.

Aviation industry anxiety about the peril of radio altimeter failure inevitably cites a Turkish Airlines Boeing 737 that crashed in 2009 while attempting a landing in Amsterdam. Nine passengers and crew members died. An investigation revealed that the disaster originated with a malfunctioning altimeter, whose faulty readings triggered the jet’s auto-throttle to cut power during the final landing approach.

The FCC’s plans to use the C-band for 5G rekindled these fears. The problem was that the upper part of the C-band is where radio altimeters operate, prompting concern that nearby 5G transmissions would cause them to spit out false readings or stop working. Because most altimeters had been built and installed decades earlier, when there was nothing noisy in their electronic neighborhood, they hadn’t been designed to screen out the likes of 5G.

Fights over the FCC’s efforts to cram ever more users into limited spectrum became unusually common, and heated, during the Pai regime, and it wasn’t just the aviation industry that protested. Other orders granting telecom companies various 5G frequencies prompted complaints that they would disrupt networks used for satellite communications, weather forecasting, agriculture, self-driving cars, global-positioning services and military weapons systems. One of the FCC actions, still being fought, drew opposition from 14 federal agencies and departments. Again and again, the FCC, backed by the Trump White House, brushed those pleas aside. “Agencies raising concerns about the impact of 5G were just sort of being mowed down by the FCC,” according to a former high-level Trump official involved in spectrum disputes.

Starting in 2018, more than a dozen aviation groups and companies told the FCC they worried that interference with radio altimeters could cause a deadly plane crash. They urged the agency to work with the FAA and delay an auction until it had identified and eliminated any risk. Aviation-industry officials also argued that the telecom companies, or the Treasury, should fund billions of dollars’ worth of altimeter upgrades to eliminate interference problems from the 5G C-band signals.

But the FCC didn’t think there was a problem to solve. The agency embraced the wireless industry’s view, which was to deny that the new 5G networks posed any risk to aviation safety.

“One of the things we built into the way spectrum auctions work is that various people need to be paid off,” said Blair Levin, who was FCC chief of staff when the agency first deployed its auctions. Levin said the 5G process was handled differently: “The airlines came and said, ‘We have this problem.’ Nobody asked: ‘What do you need to fix the problem? Do you need $2 billion? Do you need $4 billion? Do you need $6 billion?’ Ajit just said: ‘We don’t care; we don’t think your concerns are legitimate.’”

Pai defends that position. “The FCC’s career staff did a terrific job analyzing the facts,” he told ProPublica, “and had demonstrated to all the commissioners at the FCC that there was no credible case made for the possible interference with aviation altimeters… No legitimate objective engineering work would find a legitimate case for those arguments.” The FCC was the final word on spectrum allocation. End of discussion.

But that ignored a key fact: The FAA was the final word on airplane safety, and it was becoming more concerned about the risk to radio altimeters. And unlike other agencies, the FAA had sweeping authority to order dramatic steps to avoid any chance of a fatal accident.

The FAA had massive power — but it didn’t seem inclined to use it. For starters, like more than one agency under Trump, it suffered from instability at the top, with an interim leader for 18 months. And the FAA was on the defensive in the wake of two Boeing 737 MAX crashes that killed a total of 346 people and tarnished the agency’s reputation.

That meant that when Steve Dickson took over as chair in the summer of 2019, the FAA was distracted by the Boeing mess, according to an agency source. And in Dickson, the FAA seemed to have the temperamental opposite of the aggressive and ambitious Pai. Dickson, who was 61 when he took the agency helm, was a onetime Air Force fighter pilot who had recently retired from a three-decade career at Delta, first as a pilot and then as a company safety executive. (Along the way he also got a law degree.)

Perhaps because of his background in the military or perhaps just by dint of disposition, Dickson adhered strictly to the chain of command. Methodical, cautious and measured — a top deputy said he’s never heard him raise his voice — Dickson was loath to take steps outside official procedures, and those official procedures placed a lot of emphasis on filing papers. So that’s what Dickson and his agency did.

FAA Administrator Steve Dickson, shown testifying in 2021, spent a lot of his time dealing with the crisis over the Boeing 737 MAX. If Pai was aggressive and brash, Dickson tended to be rules-focused and methodical.

(Joshua Roberts/Getty Images)

Dickson did not, for example, call Pai to hash out the 5G issue. He did not march to the White House to sound the alarm. He issued no press releases to bring attention to the looming problem. The agency’s only official expression of concern in 2019 was a two-page letter from an agency engineer to a Commerce Department panel charged with resolving government spectrum disputes. It urged the FCC to delay any C-band auction until a technical study the FAA had funded had arrived and “any interference mitigations have been considered.” (Dickson declined to comment for this article.)

The FAA’s passivity was particularly striking given the mounting concern in the aviation industry. A pair of reports by aviation research groups intensified those anxieties. The first was a preliminary lab study, conducted by a government-industry research cooperative at Texas A&M University. It found all seven radio altimeters it tested were susceptible to interference. It too urged further analysis. The report was submitted to the FCC in late 2019.

But the FCC didn’t wait. On Feb. 28, 2020, it voted to authorize the C-band sale, and it scheduled the auction for Dec. 8. The FCC’s 258-page report and order devoted just six paragraphs to aviation safety, much of it agreeing with a T-Mobile-sponsored report that dismissed aviation concerns. The FCC contended that its precautions, including leaving a patch of spectrum vacant between 5G transmissions and the altimeter frequency, would be sufficient.

The FCC order made clear whose problem this was to solve. “Well-designed equipment should not ordinarily receive any significant interference (let alone harmful interference) given these circumstances,” the order stated. “We expect the aviation industry to … take appropriate action, if necessary, to ensure protection of such devices.”

The aviation companies didn’t see it that way. Their concerns escalated in October 2020 with the issuance of a 231-page report by the RTCA, a nonprofit aviation industry research organization originally known as the Radio Technical Commission for Aeronautics. It found that 5G posed “a major risk” to altimeters with “the potential for broad impacts to aviation operations in the United States, including the possibility of catastrophic failures leading to multiple fatalities.” It too urged the FCC, FAA and industries to work together to tackle the problem.

The opposite happened. The telecom and aviation industries embraced diametrically opposing views of reality. They assailed each other’s studies and methodologies. The wireless advocates declared that nearly 40 other countries had already deployed 5G on the C-band near airports, under conditions similar to those contemplated in the U.S., without incident. Aviation allies replied that power levels and other limits on 5G operations near overseas airports were meaningfully different. Each side accused the other of refusing to share technical data needed to assess the issue.

The two sides also viewed risk in radically different ways. From the aviation perspective, the wireless industry simply couldn’t fathom its hypercautious safety culture, which, given the horrific consequences of an accident, demands that any critical equipment be proven to pose a probability of failure of no more than one in a billion. “If there’s the possibility of a risk to the flying public,” the FAA’s “5G and Aviation Safety” website notes, “we are obligated to restrict the relevant flight activity until we can prove it is safe.”

Aviation companies were getting increasingly nervous. Yet the FAA continued to sit on its hands. Finally, with the 5G auction just a week away, in December 2020, the FAA took action of sorts: It drafted a letter.

What happened next involves a tiny government agency few people have heard of. Buried deep inside the U.S. Department of Commerce, it’s called the National Telecommunications and Information Administration. It advises the president on spectrum issues and mediates fights between federal agencies. Its job is to help resolve exactly the sort of conflict that was raging over 5G.

In the Trump administration, however, the NTIA was in disarray. A Government Accountability Office report would find that the agency lacked a “formalized” process for weighing in on spectrum issues. The last Senate-confirmed chief of the agency had abruptly quit in May 2019. By November 2020, it was on its third acting administrator, former Michigan State law professor Adam Candeub.

Candeub had a record as a conservative legal warrior. He’d represented a white supremacist in unsuccessfully suing Twitter for permanently barring him and his organization from its platform. He was also a fervent advocate for the FCC’s aggressive 5G agenda. Right before joining the Trump administration, Candeub published a column in Forbes titled “FCC Chair Ajit Pai Must Press Forward on 5G Auctions.” The article praised Pai for cutting “bureaucratic meddling.”

It was into these hands that the FAA and the Department of Transportation would deliver a four-page missive, dated Dec. 1, 2020, with a request that it be forwarded “expeditiously” to the FCC for public posting. Filing such a letter through the NTIA was the proper federal protocol. But the step hardly seemed to match the gravity of the problem.

Still, what the letter was asking for was remarkable: It urged the FCC to delay its C-band auction, which was just a week away at that point. Understanding “the safety and economic ramifications” of the 5G rollout required a “comprehensive risk assessment and an analysis of potential mitigation options,” the letter stated. Its tone may have been bureaucratic, but the letter contained a dramatic warning: If 5G deployment moved forward “without addressing these safety issues,” the FAA would consider imposing flight restrictions that “would reduce access to core airports in the U.S.”

This letter never made it onto the FCC’s public docket, where it would have amplified the need to resolve the dispute. Candeub never sent it.

Nearly a year afterward, when news of the letter first surfaced in media reports, and some people accused him of burying the letter to help the FCC’s agenda, Candeub, back at his old job at Michigan State, denied any political motivation. His agency’s experts, Candeub told reporters, had found “serious flaws” in the RTCA report and therefore dismissed its aviation-safety warnings.

In an interview with ProPublica, Candeub acknowledged discussing the FAA letter with Pai, who “wasn’t happy” about it. (Pai said he couldn’t recall whether or not he and Candeub had talked about the letter.) But Candeub said he’d made his decision based on a highly critical assessment of the RTCA report by Charles Cooper, head of NTIA’s spectrum management office and a career government employee. Candeub said Cooper thought the report had “serious errors.”

Emails between Candeub and Cooper, obtained by ProPublica, reveal a different narrative. In an email on Nov. 25, 2020, Cooper wrote to Candeub that, “as requested,” he and his staff had performed an initial assessment, and it indicated “agreement” with the RTCA’s approach.

“Ah … so there is a there, there,” Candeub replied. “Do you recommend, therefore, that we work with DOT for a submission to the FCC?”

“I don’t think we have a choice!” Cooper emailed back.

Asked about the exchange, Candeub insisted that Cooper reversed his view after studying the matter for a few more days. “As we dug in further, the conclusion of Charles was that this did not rise to a level of concern, so the letter wasn’t sent. … That was the final verdict I got from him.”

An NTIA spokesperson, in a statement, offered a different view: “There is no record of a staff recommendation against forwarding the letter from the FAA.” (Cooper declined to comment.) The statement also noted that NTIA staff “recommended that the RTCA study be validated and offered a path forward for better understanding the issues raised. Our work evaluating those issues is ongoing.”

On Dec. 8, the FCC commenced its auction for the C-band spectrum. The agency announced a few months later that the sale had raised a record $81.1 billion, roughly double what industry observers expected.

Verizon bought the biggest stake, for $45.5 billion, followed by AT&T, which paid $23.4 billion. Their costs for building out 5G infrastructure, marketing and paying satellite companies to speed their exit would add tens of billions more to their tab. It left the two companies, understandably, determined to exploit their investment. “We have a license from the U.S. government saying we can proceed,” explained one executive from a wireless company. “We’re not really looking for reasons why we can’t proceed.”

At that point, it appeared that the FCC had prevailed in the battle of federal agencies. Pai and Larry Kudlow, former director of Trump’s National Economic Council, would crow about how they had triumphed over Washington “swamp creatures” in a discussion on Kudlow’s Fox Business show months after both had left government. Pai insisted his agency had followed the science, and the two men denigrated concerns over aviation safety. “The FAA is bellyaching about 5G. The airlines are bellyaching about 5G. We ignored them,” Kudlow declared. “We actually fought the FAA. We won.”

As the 5G auction concluded in early 2021 and winter turned into spring, the FAA resembled the bureaucratic equivalent of a turtle that had first retracted into its shell, then been flipped onto its back. It seemed helpless. After its last-minute letter seeking to halt the spectrum auction was ignored, the agency had said nothing publicly about the issue for months.

The aviation industry was growing increasingly frantic at the FAA’s temporizing. In the summer of 2021, the agency told attendees at an industry forum that it was “still gathering information” on the radio altimeter problem. Aviation executives begged the agency to go public. “We wanted them to publicly state there is a huge problem, and it’s going to cause massive disruptions,” said John Shea, government affairs director for Helicopter Association International, a trade group. “We said: ‘You need to say this out loud! This can’t just be industry speculation.’”

Behind the scenes, though, reality was beginning to dawn at the FAA. Top officials, who had clung to the industry’s hope that somehow the FCC could be persuaded to postpone the C-band rollout for a year or two, had finally grasped that the launch was happening. The FAA simply couldn’t wait any longer if the agency wanted to follow its methodical processes and give airlines time to prepare.

Now the agency prepared to deploy its ultimate weapon: formal air-safety alerts that would pave the way for grounding commercial aircraft. By August 2021, the FAA was ready to proceed.

But a new impediment had arisen: the Biden administration. The White House was discouraging any public action, as was the FCC, which was now operating with a Democratic chair but was every bit as supportive of 5G and the telecom industry’s position on it as Pai had been. They assured the FAA that the agencies and industries could somehow still work out the problem quietly. (A senior FCC official denies the agency requested any delays.)

Repeatedly, the FAA deferred sending out its air warnings. Dickson privately told his staff that his agency was like Charlie Brown, with the White House and the FCC in the role of Lucy, who “keeps pulling the football out from under us.”

In October 2021, the FAA finally began preparing its first airworthiness bulletin, warning of “potential adverse effects on radio altimeters” — but not until its bureaucratic opponents had gotten a chance to vet the language. The bulletin received a line-by-line review from officials at the FCC and the White House’s National Economic Council, according to an FAA staffer involved in the matter. The White House “wanted to make the problem not seem as bad as it was,” the FAA official said. “And they wanted to make sure it was worded in such a way that wireless was not seen as the villain.” (The senior FCC official said his agency “routinely” provides “technical” input on bulletins. The FAA’s parent agency, the DOT, said it supported a “collaborative approach” to “minimize any disruptions to the traveling public” but that the FAA made the final call on the language of its bulletins. As the DOT put it, “Part of the process failure during the last administration was a result of auctioning the spectrum without the required collaboration between stakeholders and agencies to ensure the safety of the traveling public and minimize disruptions for them — despite consistent clear requests by DOT and FAA to do so. Conversely, this Administration wanted to ensure that government agencies with technical expertise were all at the table and collaborating.”)

Issued on Nov. 2, 2021, the bulletin alerted equipment manufacturers, aircraft companies and pilots to the potential for “both erroneous altimeter readings and loss of altimeter function.” This, the bulletin advised, could result in “the loss of function” of safety systems. It added that the FAA was assessing whether potential limits on flight operations were warranted.

That threat instantly transformed the standoff. “That kicked in some action,” a wireless-industry executive said. “That’s the first time they said to the airlines: ‘When these guys light up on Dec. 5, we’re going to ground your planes.’” The executive added: “All of a sudden, we needed to tackle a two-year problem in 30 days.”

Two days after the FAA’s airworthiness bulletin went out, Verizon and AT&T agreed to a one-month delay, pushing the 5G start date to Jan. 5, 2022. With threats of aviation shutdowns now officially in play, no one wanted to be blamed for ruining holiday travel.

Now the question became how broad and long-lasting any restrictions on the 5G rollout should be. The telecom companies, backed by the White House and FCC, wanted them to be limited and temporary. The FAA and aviation interests wanted something far more sweeping and permanent.

Haggling commenced in earnest. Verizon and AT&T had already offered to modestly cut power from some 5G transmitters near runways for six months. The aviation companies rejected that as “inadequate and far too narrow.” They proposed a broad swath around airports where towers would never be turned on as well as other limits. No way, countered the FCC. That would render the telecoms’ C-band spectrum “commercially unviable. … Effectively it would cease to be 5G.” FCC officials felt that the telecom industry was being falsely cast as a villain.

But momentum had turned in favor of the aviation forces. The mere specter of fatal airplane disasters was a potent message. The wireless companies were getting hammered in the press, with news reports warning that 5G could cause planes to crash.

Negotiations intensified. In late December 2021, Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg jumped in, talking with the CEOs of Verizon and AT&T. Buttigieg announced a truce on Jan. 3. The wireless companies agreed to another two-week delay and to establish temporary modest 5G-free buffer zones around 50 airports for six months. And they’d provide the FAA with full details about their tower sites.

But almost as fast as it was announced, the deal fell apart. Altimeter testing made clear that the planned buffer zones weren’t nearly big enough to resolve the FAA’s interference fears.

The once-somnolent agency was now firing a fusillade of safety notices, laying out the specifics of how each airport would be affected. Thousands of planes would need to be barred from landing in low-visibility conditions at airports where 5G was present. Some big long-haul jets wouldn’t be able to fly into airports with 5G at all. One FAA notice warned that C-band interference might prevent braking systems on some Boeing 787s from kicking in during landings, causing planes to speed off runways.

Buttigieg and the FAA’s Dickson went back to the CEOs of Verizon and AT&T and demanded yet more concessions. On Jan. 18, the companies capitulated, even as AT&T bitterly complained that the FAA and aviation industry had “not utilized the two years they’ve had to responsibly plan for this deployment.”

When Verizon and AT&T finally switched on their networks the next day, the expanded restrictions (a 3-mile buffer zone around 87 airports) left more than 600 of their 5G towers dark — about 10% of their planned first-day service.

The last-minute chaos spurred a flurry of flight cancellations. But the provisions, and continued testing of radio altimeters, allowed about 90% of planes to operate normally within days. A conspicuous exception was about a thousand Embraer regional jets, used by JetBlue, American, Delta and other airlines. Equipped with altimeters particularly susceptible to interference, they remain restricted from landing in poor-weather conditions in many cities with C-band towers.

The former adversaries finally began to collaborate. The FAA built a measure of trust with Verizon and AT&T by allowing them to turn on enough towers to showcase their 5G service at the Super Bowl on Feb. 13, even though the stadium was beneath a landing approach to Los Angeles International Airport. As the weeks passed, both sides made more accommodations, shrinking the size of the buffer zones while boosting the total number of “protected” airports to 114.

Most participants in the 5G process say comity and cooperation has increased among all parties. AT&T told ProPublica in a statement that it is “continuing to cooperate and collaborate with the FAA, FCC and other stakeholders to help facilitate the FAA’s technical assessments and clearance of aviation equipment. We are encouraged by the significant progress the FAA has made thus far, and we expect that progress will continue going forward.” Verizon also said it was “encouraged” by the “collaboration and pace” among the companies and agencies, adding, “We’re highly confident that the small and declining number of outstanding questions will be resolved sooner than later, without any meaningful impact to airline operations or the availability of 5G at airports.”

For all the expressions of optimism, the problems aren’t yet resolved and a deadline looms: Verizon and AT&T have made no commitment to extend their “voluntary” restrictions beyond July 5. And this may not be the last such battle, either: In December 2023, T-Mobile and other wireless companies will be free to fire up a new patch of C-band, even closer to the altimeter frequency. At that point, 5G will be operating near hundreds of additional airports.

In the face of this uncertainty, aviation companies are scrambling to develop the only promising short-term solution: filters designed to screen out electronic interference for the worst-performing radio altimeters. But many altimeters can’t be fitted with filters and inventing and deploying new altimeters for a 5G world will take years. Meanwhile, the industry is continuing to agitate for someone else to pay for it all.

In recent months, the center of activity in the 5G saga has been the FAA, which is now led by an interim chief. (Dickson announced his resignation in February, saying it was “time to go home”; he left in March.)

The FCC, more on the fringes at this stage of the process, has been talking about steps like improving its processes with the NTIA, while continuing to insist that claims of 5G risk are hooey. AT&T echoed that sentiment, saying “the physics has not changed,” in a second statement it sent to ProPublica, in late May. The company’s hope, in this statement, was beginning to sound like it was being uttered through gritted teeth. AT&T is still “working collaboratively with the FAA and the aviation industry,” it said, while noting that “we have made no additional commitments beyond July 5, but are in discussions with the FAA and aviation on a phased deployment approach that will provide the aviation industry with some additional time to complete equipment updates without stalling our C-Band deployment.”

At the FAA, it seemed like one step forward, one step back as the July 5 deadline approached. On May 4, the agency convened an in-person gathering of 40 invited “stakeholders” from the wireless and aviation industries — but no FCC officials — aimed at forging a path for continued peace. Agency officials reviewed the “rapid evolution” in easing the limits on the wireless companies around airports. And they pressed aviation officials to develop a firm timetable for retrofitting the entire U.S. commercial fleet with filters and new altimeters, in short, a day when 5G can finally be unfettered.

But barely more than two weeks later, on May 19, the follow-up meeting with the FAA sounded considerably less encouraging. One company that is preparing filters for altimeters pleaded for time, saying it needed until the end of 2023. That’s not good enough, the FAA’s acting chief responded. He told them it needs to happen by the end of this year.

Efforts to reach accommodation had increased, it seemed, but so had “heartburn,” as one FAA official put it. “The wireless companies have made it very clear they’re not going to agree to an open-ended situation,” he said. “They seem willing to go past July 5, as long as they know how far past. But they’re making clear their patience is not infinite.”

Doris Burke contributed research.

Embedded illustrations by ProPublica. Source Images: The7Dew and Peng Song/Getty Images.

This post was originally published on Articles and Investigations – ProPublica.