by Cezary Podkul

]

ProPublica is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up to receive our biggest stories as soon as they’re published.

Consider some of the episodes last year in which large quantities of personal data were stolen: 300 million customer and device records for users of a service that’s supposed to shield internet traffic from prying eyes; a 17.6-million-row database from a second organization, containing profiles of people who participated in its market research surveys; 59 million email addresses and other personal data lifted from a third company. These sorts of numbers barely raise an eyebrow these days; none of the incidents generated major press coverage.

Cybertheft conjures images of high-tech missions, with sophisticated hackers penetrating multiple layers of security systems to steal corporate data. But these breaches were far from “Ocean’s Eleven”-style operations. They were the equivalent of grabbing jewels from the seat of an unlocked car parked in a high-crime neighborhood.

Never miss the most important reporting from ProPublica’s newsroom. Subscribe to the Big Story newsletter.

In each case, the companies left the data exposed online with little or no security. So says Pompompurin, a pseudonymous hacker who posted the millions of stolen records cited above on RaidForums, a discussion board popular with cybercriminals seeking personal data. Pompompurin told ProPublica that he often doesn’t need to do much hacking to get his hands on sensitive personal data. Many times, it’s left in cloud storage folders available to anyone with internet access. Pompompurin said he scans the web for such unguarded material and then leaks it on RaidForums “because I can and it’s fun.”

The exposed data extends far beyond what can be found on RaidForums, ranging from the prosaic and useless to the ultravaluable. In recent years, it has included everything from names, emails and chat transcripts of users of a sex cam website to America’s secret terrorist watch list to a virtual hard drive from the federal government with sections classified as “top secret.”

Such incidents helped make 2021 a record year for data breaches, according to the Identity Theft Resource Center. Data exposure events, in which sensitive data is left sitting online, were responsible for cybersecurity incidents involving an estimated 164 million of the 294 million people victimized in 2021, according to the center.

For years, companies have been vowing to harden their electronic defenses as cybersecurity firms repeatedly warned them about the pitfalls of this form of laxity. But to little avail. “It keeps happening because people commonly forget or they just think it’s private when it isn’t,” Pompompurin told ProPublica.

There’s another reason, one that companies don’t like to talk about: It’s often cheaper to clean up a breach than it is to avoid one in the first place. Corporate losses from a data breach typically run around $200,000, according to a recent study of 56,000 cybersecurity incidents published by the Cyentia Institute, a cybersecurity research firm.

The low costs don’t justify investing more in data security, according to Sasha Romanosky, a researcher at the RAND Corporation who has studied the issue. “The companies don’t bear the cost of these actions,” Romanosky said. “It is borne by the consumers.”

The tab for taxpayers is mammoth. Identity theft enabled what may turn out to be the biggest fraud wave in U.S. history, siphoning off tens if not hundreds of billions of dollars of unemployment insurance payments, small business loans and grants. For unemployment insurance systems alone, estimates of the loss have ranged from around $90 billion to $250 billion or more. Whatever the ultimate figure, it will fall on the shoulders of taxpayers.

Meanwhile, vast quantities of data remain undefended. About 8 billion files are exposed across cloud storage folders on the internet, according to Grayhat Warfare, a service that monitors open cloud storage folders and lets users search their contents. And a total of at least 7.2 million databases are exposed online, according to an internet scan performed for ProPublica by Censys, a search engine that catalogs internet-connected devices and services, ranging from database servers to computers managing drive-thru restaurants to surveillance cameras.

The result is that gathering personal data on individuals is easier today than it was a decade ago, said Ngô Minh Hiếu, a reformed hacker who once ran an online store offering up personal data on about 200 million Americans. Stores like the one he once ran have proliferated online in recent years. “The information, it just sits there waiting for you to get it,” Hiếu said.

Hiếu is now a so-called white hat hacker, seeking to identify black hats, like Pompompurin, and help companies guard against vulnerabilities they may exploit. But when it comes to exposed data in the U.S., the black hats are winning.

Americans rarely get a glimpse of hackers, much less what their work entails. They might be surprised to learn how little experience is needed. People often think hackers are highly sophisticated, Troy Hunt, creator of data breach tracking website Have I Been Pwned, told ProPublica. But in reality, there’s so much unsecured data online that most of the 11.7 billion email addresses and usernames in Hunt’s collection come from young adults who watch a few instructional videos and figure out how to grab them for malicious purposes. “It’s coming from kids with internet access and the ability to run a Google search and watch YouTube videos,” Hunt said in a 2019 talk about how hackers gain access to data.

Hiếu was once one of those teenagers. He grew up in a Vietnamese fishing town where his parents ran an electronics store. His dad got him a computer at age 12 and, like many adolescents, Hiếu was hooked.

His online pursuits quickly took a wrong turn. First, he started stealing dial-up account logins so he could surf the web for free. Then he learned how to deface websites and abscond with data left exposed on them. In high school, he joined forces with a friend who helped him pilfer credit card data from online stores and make up to $500 a day reselling it.

Eventually fellow hackers told him the real money was in aggregating and reselling Americans’ identities. Unlike credit cards, which banks can cancel instantly, stolen identities can be reused for various fraudulent purposes.

Beginning around 2010, Hiếu went looking for ways to get detailed profiles of Americans. It didn’t take long to find a source: MicroBilt, a Georgia-based consumer credit reporting firm, had a vulnerability on its website that allowed Hiếu to identify and take over user accounts. Hiếu said he used the credentials to start querying MicroBuilt’s database. He sold access to the search results on his online data store, called Superget.info.

MicroBilt spotted the vulnerability and kicked Hiếu out, setting off a monthslong standoff during which, Hiếu said, he exploited several vulnerabilities in the company’s systems to keep his store going. MicroBilt did not respond to requests seeking comment.

Tired of the back and forth, Hiếu went looking for another source. He found his way into a company called Court Ventures, which resold aggregated personally identifiable information on Americans. Hiếu used forged documents to pretend he was a private investigator from Singapore with a legitimate use for the data. He called himself Jason Low and provided a fake Yahoo email address. Soon, he was in.

Ngô Minh Hiếu in Ho Chi Minh City

(Yen Duong, special to ProPublica)

Hiếu’s fake account turned Superget.info into a go-to destination for cybercriminals, what U.S. prosecutors later described as the Amazon of stolen identities. In essence, Hiếu was a wholesaler, dealing search results for particular details like driver’s licenses or Social Security Numbers or packages of identity information. He offered individual and bulk search plans and allowed cybercriminals to resell the data in their countries via reseller arrangements. One of his biggest resellers was a Russian going by the alias “Devil.” Other customers were located in the U.S., Ukraine, Brazil, Romania, Vietnam, Ghana and Nigeria, according to Matt O’Neill, a senior special agent at the U.S. Secret Service, which began investigating Hiếu in 2011. By distributing the data so widely, Hiếu “caused more material financial harm to more Americans than any cyber fraudster,” O’Neill said.

By the time he was 22, Hiếu estimated, he was earning $100,000 to $150,000 a month in a country where the average person earns less than $200 per month. He splurged on luxury cars, like a customized Hyundai, a BMW and a Lexus, and got himself a $10,000 cellphone. He treated his family to vacations at high-end resorts and helped his parents repay some debts. When they asked how he was making his money, recalled his sister Ngô Nora, he’d say he was creating websites.

Hiếu’s empire began to unravel when the Secret Service alerted Court Ventures’ parent company, Experian, to his activities, and the firm cut off his data access. (Experian has said it didn’t know about Hiếu’s fake account with Court Ventures when it bought the company in 2012. A spokesperson said the company is “deeply committed to helping consumers protect their data from today’s increasingly sophisticated cyber criminals.”)

Addicted to his opulent lifestyle, Hiếu went looking for another data source. O’Neill, the Secret Service agent, saw an opening: He convinced a cooperating defendant in another case to message Hiếu and offer him the promise of an even better data source than Experian — but only if he’d meet with another contact in the U.S. territory of Guam to strike a deal.

Hiếu resisted the entreaties at first, O’Neill recalled in an interview. But in February 2013 Hiếu gave in and hopped on a flight to Guam. Soon after he landed, finally putting him within reach of U.S. law, the Secret Service arrested him.

Facing up to 45 years behind bars, Hiếu agreed to cooperate and pleaded guilty to multiple counts of fraud. He let O’Neill use his email and online persona to talk to his customers. O’Neill said he spent two years asking them why they were seeking to buy people’s personal information. Most said they wanted the data so they could file fake tax returns in other people’s names and obtain the refunds. The Internal Revenue Service estimated that nearly 14,000 victims had fraudulent tax returns filed in their names claiming a total of $65 million in refunds using data from Hiếu’s store. Evidence gathered by O’Neill helped in the prosecution of about two dozen of the perpetrators.

Hiếu said he had never wondered why his customers wanted data. “It’s just numbers, information,” he told himself when he ran his website. It was only after he was sentenced to 13 years in prison in July 2015, he said, that he realized the harm he had caused.

Hiếu was shuffled among local and federal prisons in New Hampshire, Ohio, Louisiana, New Jersey, New York, Mississippi and Texas as he cooperated with authorities in various cases against his former clients. The low-security prisons gave him an opportunity to keep in touch with the outside world and to rehabilitate himself, which he’d vowed to do.

Hiếu completed anger management and life skills classes, according to court records, and attended group counseling sessions during his stay at a county jail in Dover, New Hampshire. He started reading the Bible. His counselor at the Dover jail, Minnett Induisi, said Hiếu took responsibility for his actions. “In all my years of working at the jail, I have never seen someone so committed to making himself a better person,” said Induisi, who has taught at the jail for 41 years.

In 2016, Hiếu wrote a long email to the assistant U.S. attorney who had prosecuted his case. It detailed his acts, including the MicroBilt and Experian hacks, along with his theft of 100,000 credit card details from a U.K. retailer and personal data from U.S. and Canadian payday lenders. He wrote that he found his targets by running a service that scanned the internet 24 hours a day to find vulnerabilities in websites that he could use to steal data.

Hiếu said he wrote the email because he no longer had anything to hide. He dreamed of returning online not as a cybercriminal but as a researcher who would help catch cybercriminals. To maintain his skills and keep up with cybersecurity news, he used tablets in prison libraries, read books and wrote a digital security guide for the average person. He called it “Online Security Tips From a Former Hacker” and vowed to publish it when he left prison.

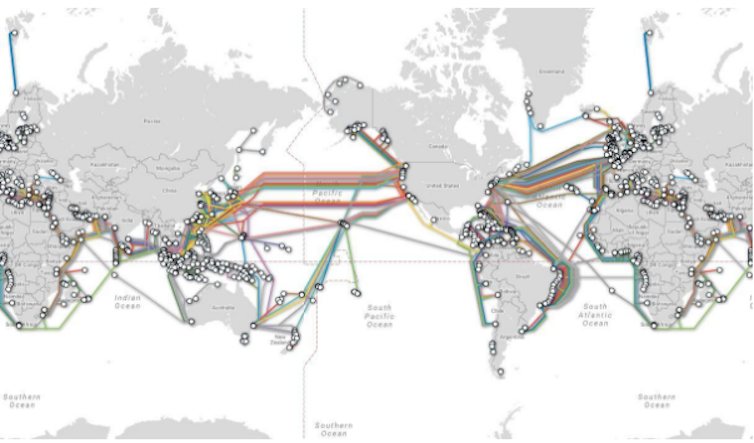

The need for white hats, Hiếu could see, was exploding. Hacking itself was as old as computer networks, but the rise of cloud computing had multiplied the opportunities exponentially. Governments and businesses around the world had embraced the cloud, migrating ever more data and software from their own computers to remote servers accessed via the internet. The move revolutionized e-commerce, making it easier and faster to store data, share files, stream videos, develop apps, collaborate and create new software and technology of all sorts. The trend, well under way in the first decade of the century, only accelerated in the 2010s.

The speed of the migration had a downside. In their rush to embrace cloud computing, businesses and governments often forgot to secure the data they were moving into the cloud. Often, the failure to change a single setting on a database server or a storage folder on a cloud service meant the difference between keeping it private or exposing it to the world.

Anyone looking to find unprotected data could fire up a specialized search engine and start sifting through the internet like a prospector searching for gold. In mid-2015, Chris Vickery, an IT help desk technician at a Texas law firm, started using one such search engine called Shodan to identify devices and services connected to the internet. Within months, he discovered a trove of customer data belonging to MacKeeper, a popular antivirus tool for Mac users. “I have downloaded over 13 million accounts’ details from a publicly accessible and completely exposed database,” he wrote in a Dec. 14, 2015 email alerting MacKeeper to the vulnerability.

Volodymyr Diachenko was on the receiving end of that alert, which prompted a swift response from MacKeeper. At the time, he was a PR manager for the company, based in Ukraine. Vickery’s discovery prompted Diachenko to team up with Vickery and start hunting for similar vulnerabilities. “It was so alarming and disturbing that I wanted to learn more about how it happened and to start alarming other companies about how much they have exposed,” Diachenko said in an interview. Diachenko and Vickery found massive quantities of untended data, including passport data and Social Security Numbers, scattered across the web.

Black hats took notice, too. In 2015, an individual calling himself Omnipotent launched RaidForums, an online message board where hackers could advertise leaked databases and store them for easy retrieval. The website became the destination of choice for black hats looking to share data or auction off their finds to the highest bidder, aggregating billions of leaked records across thousands of data dumps.

A person who responded to messages directed to Omnipotent told ProPublica that he founded RaidForums because he believes in freedom of information: “And what I mean specifically is that if a hacker is in the dark web selling a database with your information you should yourself be aware of it and able to access that data for free through my services or similar.” Omnipotent acknowledged that individuals with malicious motives may access the data as well, “but that’s no reason to just stop making data free.”

Similar sites increasingly abound. WeLeakInfo offered personal information obtained in over 10,000 data breaches containing some 12 billion searchable records until it was shut down by authorities in 2020. Analysts for cyber threat intelligence firm Flashpoint have noticed about 100 websites offering up stolen identities over the past year. ProPublica spotted similar services operating on the messaging app Telegram, which abruptly shut some of them after our inquiry.

The proliferation of such sites is crucial to the techniques used by cybercriminals. They often combine pieces of stolen information from various sites to build profiles of targets for exploitation. It’s why hackers often build huge collections of leaked databases and “trade them like Pokemon cards,” said Allison Nixon, chief research officer at cybersecurity investigation firm Unit 221B.

What has become an ongoing war between white hats and black hats necessitates vigilance and swift action. When Diachenko intentionally left a database exposed in 2020 to see how long it would take for it to get noticed and accessed, the first intrusion came just 8 hours and 35 minutes after it went live, followed by 174 more over 12 days. The experiment ended when an attacker deleted the database contents and left a ransom note demanding a Bitcoin payment to avoid having the data posted online.

Often it’s not clear if companies take any action in response to warnings from white hats. On Oct. 8, Diachenko discovered the collection of 300 million customer and device records for users of several virtual private networks, which help internet users shield their web traffic. He alerted the company that owned the services, ActMobile Networks, but did not get any response for nearly three weeks. (ActMobile didn’t reply to ProPublica’s inquiries.) Eventually, ActMobile denied having any databases and threatened to “take action” against Diachenko if he wrote about his discovery. By then, black hats had noticed the data as well. On Nov. 1, the records made their debut on RaidForums.

That data was posted by Pompompurin, who joined RaidForums in October 2020 and quickly became one of its most active members. Pompompurin, whose alias was borrowed from a Japanese cartoon dog, told ProPublica that he has leaked around 20 databases online and has more than 100 “on my pc just chilling.”

Collecting and sharing data isn’t just a pastime for him. It’s also a commercial enterprise at times. After another hacker obtained customer data from the stock-trading app Robinhood in November, Pompompurin helped sell the material, posting an ad on RaidForums seeking bids for the spoils. “No lowball offers,” the advertisement read. “This is highly profitable if in the right hands.” He confirmed that he sold it, but wouldn’t say for how much.

The ease with which companies’ data can be harvested led Pompompurin to write a blog post praising ransomware. The post argues that the high cost of ransom might finally prompt companies to take data security seriously.

Pompompurin appears to be a sort of nondenominational hacker, targeting not only lax companies, but even other cybercriminals. For example, he figured out a way to get a copy of the credit card details for customers of WeLeakInfo. He dumped those online too.

Pompompurin is happy to discuss his activities and his philosophy, but not his identity. (Pompompurin was willing to confirm that his preferred personal pronoun is “he.”) Still, some clues about his potential identity may be starting to appear as he spars online — black hat vs. white hat — with a cybercrime investigator named Vinny Troia, who has been researching his activities and recently purported to unmask him.

In November, Troia published a blog post tracing the Pompompurin alias to a cybersecurity professional in Calgary, Alberta, named Chris Meunier. Meunier started hacking around the age of 14, according to Troia, cycling through various online aliases as he collaborated with a childhood friend on data heists conducted by a fearsome hacking group known as the Dark Overlord. (A website for a Calgary-based company called WhitePacket lists its proprietor as Meunier. He did not respond to emails seeking comment and could not be reached by phone.)

Pompompurin denied that he’s Meunier in a message exchange with ProPublica and in a Nov. 16 blog post on his website. Pompompurin describes himself on his site as a “threat actor, website administrator and proud Canadian.” He has retaliated against Troia, including by commandeering an FBI email alert system and using it to send out fake emails about him. Pompompurin told ProPublica he did that “because it was fun.”

Pompompurin’s public jousts with Troia reveal the hacker’s thinking. In April, when Pompompurin published a post on RaidForums unveiling the trove of 59 million email addresses and other information on tens of millions of Americans, he also posted a screenshot of a chat with Troia about whether to make the data available. Troia urged him not to do so.

“What would you gain by leaking it,” Troia asked.

“Nothing,” Pompompurin responded.

“Then why do itb,” Troia asked.

“Because I wanna,” he answered.

“Just to expose more peoples info,” Troia responded.

“Yes,” Pompompurin said.

Photos of Hiếu before and during his time in prison. He was 23 when he was arrested.

(Yen Duong, special to ProPublica)

White hats gained a new recruit when Hiếu returned to Vietnam in August 2020 after seven and a half years in prison, about six years earlier than expected thanks to his cooperation and good behavior.

Hiếu was shocked when he realized how much he’d missed while in prison. His sister Nora had gotten married and had a child. His ex-girlfriend, who broke up with him while he was in prison, was in a new relationship and about to marry someone else.

Once Hiếu adjusted to his new life in Ho Chi Minh City, he published his online security guide and went looking for a job. The Vietnamese government hired him as a researcher at its National Cyber Security Center, where his job involves monitoring RaidForums and similar platforms for black hats who seek to exploit Vietnamese targets. “I love it because I chase those people who I was before,” he said. Hiếu hasn’t crossed paths with Pompompurin, but said he saw a bit of his younger self in the hacker: “I just feel like I was that kind of guy back in the day.”

When Hiếu comes across hackers whose activities may be of interest to U.S. law enforcement, he sends tips to O’Neill, the Secret Service agent who helped put him in prison. O’Neill confirmed that Hiếu has provided the agency “credible and actionable” intel.

One thing immediately became clear to Hiếu after he started his current job: “It’s a lot easier and a lot faster to do cybercrime nowadays,” he said. When Hiếu was running his stolen-data store a decade ago, he often dealt with his customers via email, which exposed him to wire fraud charges tied to the U.S.-based email service he used. Nowadays, cybercriminals can just set up their own channels on Dubai-based Telegram and instantly advertise their services or stolen data to customers all around the world. When they find buyers, they can strike deals via encrypted chat messages, which are difficult for law enforcement to access, especially for those sent via services based outside of the U.S.

“We can’t get the chats,” said Jason Kane, special agent in charge of the Secret Service’s Criminal Investigative Division. “It’s not like the old days of a wiretap where you tap someone’s phone under a legal process and you were able to hear the bad actors talk about the bad activity.”

A December advertisement for a chatbot offering to sell personal data, posted by @TomsShop in a Telegram channel called FullzShopDL. Telegram deleted the channel and its chatbots after ProPublica inquired about them.

(Screenshot from Telegram)

Hiếu showed ProPublica some of the services that thrive in this ecosystem. They include fully automated Telegram chatbots that spit out Americans’ identities on demand. One of these, known as the Hornet Lookup Bot, offered instant access to Social Security numbers for $10 each and driver’s licenses for $40. A Russian chatbot offered a similar service for the U.S., the United Kingdom and Canada. Yet another chatbot purported to be able to open bank accounts in any state using a stolen identity, according to touts from a Telegram user named @TomsShop in a channel called FullzShopDL. Most of the payments in such venues now occur in Bitcoin, which is hard to trace.

Telegram shut down the Hornet Lookup Bot, the Russian chatbot and @TomsShop’s sales channels after ProPublica asked about the services, but the company did not answer questions about why it allowed them to operate in the first place. (Rep. James Clyburn, D-S.C., recently posed similar questions in a letter to Telegram founder Pavel Durov that cited ProPublica’s July report about how cybercriminals were using the messaging platform to help each other file fake unemployment insurance claims. In September, Durov posted a message in his Telegram channel saying that “Telegram gives its users more freedom than any other app. If Telegram has to temporarily remove some content due to a law, it means that other platforms would have removed it long before us.” A spokesperson for Clyburn said Telegram has “refused to engage” with Clyburn’s committee.)

Not surprisingly, stores that sell stolen data quickly pop back up after they’re shut down. Cybercriminals often simply recycle their old usernames with a new digit or an extra letter at the end, and they’re back in business. The Hornet Lookup Bot is back in service on Telegram, now calling itself a “search” bot, and @TomsShop resurfaced under the handle @TomsShopz.

There’s no shortage of data leaks to help restock such services. When black hats steal data, posts quickly pop up on Telegram and RaidForums offering access to the information. After T-Mobile suffered a serious breach of its servers in July, an ad popped up on RaidForums offering 30 million Social Security and driver’s license numbers that were purportedly harvested from the heist. “Freshly dumped and NEVER sold before!” the August post enthused. (A spokesperson for T-Mobile, which has suffered at least five data breaches since 2018, said the company is creating a cyber transformation office that will create a “security-forward mindset.”)

Personal data posted in a Telegram channel with the message “Free one!” as an enticement to new customers

(Screenshot from Telegram)

Once stolen data is no longer fresh, like many products, its price gets marked down, or it’s offered as a free enticement to attract new customers. One Telegram channel spit out random Americans’ Social Security numbers, addresses, driver’s licenses, dates of birth and names along with the message “free one!” mixed in between ads for full packages of identity information for $3 each. “It’s very easy to obtain data that belongs to U.S. people,” Hiếu said.

In November 2020, drivers in Texas got an unpleasant surprise when a software company called Vertafore, whose clients include auto insurers, revealed that it had left 28 million Texas driver’s license numbers sitting unsecured online. Three weeks later the company discovered that one of its products had been leaving reports containing names, addresses, birth dates and driver’s license numbers publicly accessible for about eight years, according to a notice filed in another state.

Fourteen months later, no federal or state agency has taken any public action in response, though the state of Texas has said it is investigating the breach. Vertafore did not reply to emails seeking comment. (At the time of the driver’s license leak the company said it “takes data privacy and security very seriously.”)

The U.S. doesn’t have comprehensive federal laws governing data security. So the burden has fallen to states. About half have enacted laws requiring companies to implement and maintain security procedures to prevent unauthorized access to personal information.

Companies occasionally face regulatory penalties for leaving data exposed online, but they don’t amount to much. In 194 instances cataloged by insurance data provider Advisen, most of them after 2008, companies have paid fines and penalties for leaving data unprotected, totaling about $71.6 million. That’s an average of about $369,000 per incident involving a fine or penalty.

All 50 states have enacted laws requiring notifications in case of data breaches. But consumers are often still left in the dark about whether they’ve been affected. Most states let the organizations that lost control of the data decide whether they need to issue a notification. When they do, a press release is often enough to satisfy state laws.

“It should be pretty clear by now that breach notification has failed to actually inspire effective data security protections across the board,” said Harley Geiger, head of public policy at Rapid7, a Boston-based cybersecurity firm. Geiger said a national baseline standard is needed to prompt businesses to implement appropriate data security protections.

The European Union has been operating under such a standard since May 2018. Known as the General Data Protection Regulation, the law requires companies to implement security measures to protect sensitive personal data and to promptly notify regulators and affected consumers when it gets compromised. Violations of the data protection rules can result in fines as high as 4% of a business’s annual worldwide sales. “You have to implement cybersecurity measures if you process personal data, and if you do not, you will have a legal problem,” said Stefan Hessel, a cybersecurity specialist in Germany at the Reuschlaw law firm.

Such measures may in fact make it harder for hackers to ply their trade, if Pompompurin’s postings are any indication. In August he was asked on RaidForums why large collections of personal data always seem to come from the U.S. He responded: “Because its the easiest to get, other countries have load of protection laws & shit, in the US your address is basically public information no matter how hard you try not to be put on lists like this.”

The Federal Trade Commission has been asking Congress to bolster its legal authority for more than a decade by enacting legislation that would set nationwide standards for data protection and breach notification. Sen. Maria Cantwell, D-Wash., and Sen. Roger Wicker, R-Miss., have each introduced bills that would require companies to implement and maintain reasonable data security practices to protect sensitive data and enable the FTC to more easily fine companies that suffer data breaches because of their own negligence. The two Senators are talking about combining their bills, according to a Senate committee staffer.

Pompompurin doesn’t seem concerned. In June, he organized 155 leaked databases into a neat index for RaidForums users. It included some of his greatest hits, and he invited others to submit their favorites. As he put it, “There’s a LOT of good dumps on here that should get more recognition.”

His effort was met with adoration. “Thanks for your hard work,” one RaidForums user responded, “we will get more data.”

Do You Have a Tip for ProPublica? Help Us Do Journalism.

This post was originally published on Articles and Investigations – ProPublica.