The economic consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic have brought calls for a universal basic income. While it’s no silver bullet, they can allow workers say no to the most thankless, low-wage work, providing a platform from which to rebuild our bargaining power.

AN INTERVIEW WITH DANIEL RAVENTÓS by Àngel Ferrero

The economic consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic have brought calls for a universal basic income (UBI) back into the spotlight — and so, too, criticisms of it. This is especially the case in Spain, where a more conditional “minimum living income” project introduced by the left-wing coalition government has been undermined by poor delivery and only limited take-up by those entitled to the scheme.

A possible way forward comes from autonomous Catalonia. Following the recent elections there, the anti-capitalist Candidatura d’Unitat Popular (CUP) has agreed to give its support to a government of the soft-left Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya (ERC), through a pact which includes the approval of a pilot program for full UBI.

Daniel Raventós is a professor at the Faculty of Economics and Business at the University of Barcelona, as well as the president of the Red Renta Básica. He spoke to Àngel Ferrero about the pilot, its limits and the potential uses of UBI.

AF: You’ve been researching UBI for more than twenty years. How would you define it, in concise terms?

DR: A universal and unconditional public monetary allowance.

AF: Although UBI is not yet a reality, there have been several pilot projects. What have the results been?

DR: There have been trial runs in many different geographical and political contexts, from Finland to Canada to Namibia. Not all these projects have been implemented in the same way, which sometimes makes it difficult to compare them.

These experiments have many limitations. One of the main ones is that they can’t show some of the major effects UBI would have on society as a whole: in particular, increased bargaining power for workers and women. The people receiving the UBI in the pilot projects tend to be isolated from each other, so it’s hard to judge their aggregate effects.

Clearly, planning your life with a UBI you expect to have for two or three years is something very different from planning your life with the expectation of a lifetime UBI. But these experiments do allow us to evaluate, with all the limitations I have mentioned, partial aspects such as the effects on mental health. In each of these cases, mental health improved. Which is no small thing.

AF: But with a UBI, are the material conditions of existence guaranteed?

DR: Not with this alone, of course.

UBI must be understood as one policy measure, not as a complete economic policy unto itself.

An economic policy includes fiscal, monetary, labor measures… and, for me, a maximum income, too. A few people having huge fortunes is a threat to the freedom of the majority — and you don’t even have to be a socialist or republican to recognize that.

AF: In Catalonia, two parties recently reached an agreement for government, including a UBI pilot program. What is the status of the negotiations?

DR: Well, the agreement talks about the implementation of a pilot plan in certain age groups of UBI in three temporary phases. This is a very moderate, very reasonable, very measured move — which has already sparked the ire of both the pro-independence Catalan right and Spanish monarchists. And also of a certain kind of left who have great respect for, and servility toward, the status quo. It is funny to see the allergies this proposal provokes among some politicians and technocrats, even just when it’s a trial scheme.

As far as I know, both the [anti-capitalist] CUP, which had UBI very clearly in its electoral program and made it one of the main axes of its campaign, and the [soft-left] ERC, which referred to the UBI as a longer-term measure, seem to be standing firm for this policy.

AF: How could such a measure be financed?

DR: Catalonia has nothing like fiscal sovereignty. The financing proposal that Jordi Arcarons, Lluís Torrens, and I have been investigating with some variations in recent years is based on a major reform of personal income tax, so that 80 percent would pay less tax with UBI and the richest 20 percent would pay more. Catalonia does not control 100 percent of income tax. That’s the way things are. Many people who are for a Catalan Republic consider UBI, along with other clearly progressive measures, are a good reason to want to become independent from the Spanish monarchy.

Even so, it’s also true that the Catalan government does have the power to pursue a much more ambitious economic policy than the one it’s carried out in recent years. One of the aforementioned economists, Lluís Torrens, more than two years ago proposed a series of measures within the limits of Catalonia’s current autonomous powers, to finance UBI. Very briefly, these included: a wealth tax, reversing the inheritance and gift tax to 2008 levels, increasing environmental taxes, gambling tax revenues, and some modifications to personal income tax.

AF: The COVID-19 pandemic has led to basic income being widely considered as a proposal to overcome this crisis. What are the advantages of basic income compared to other measures?

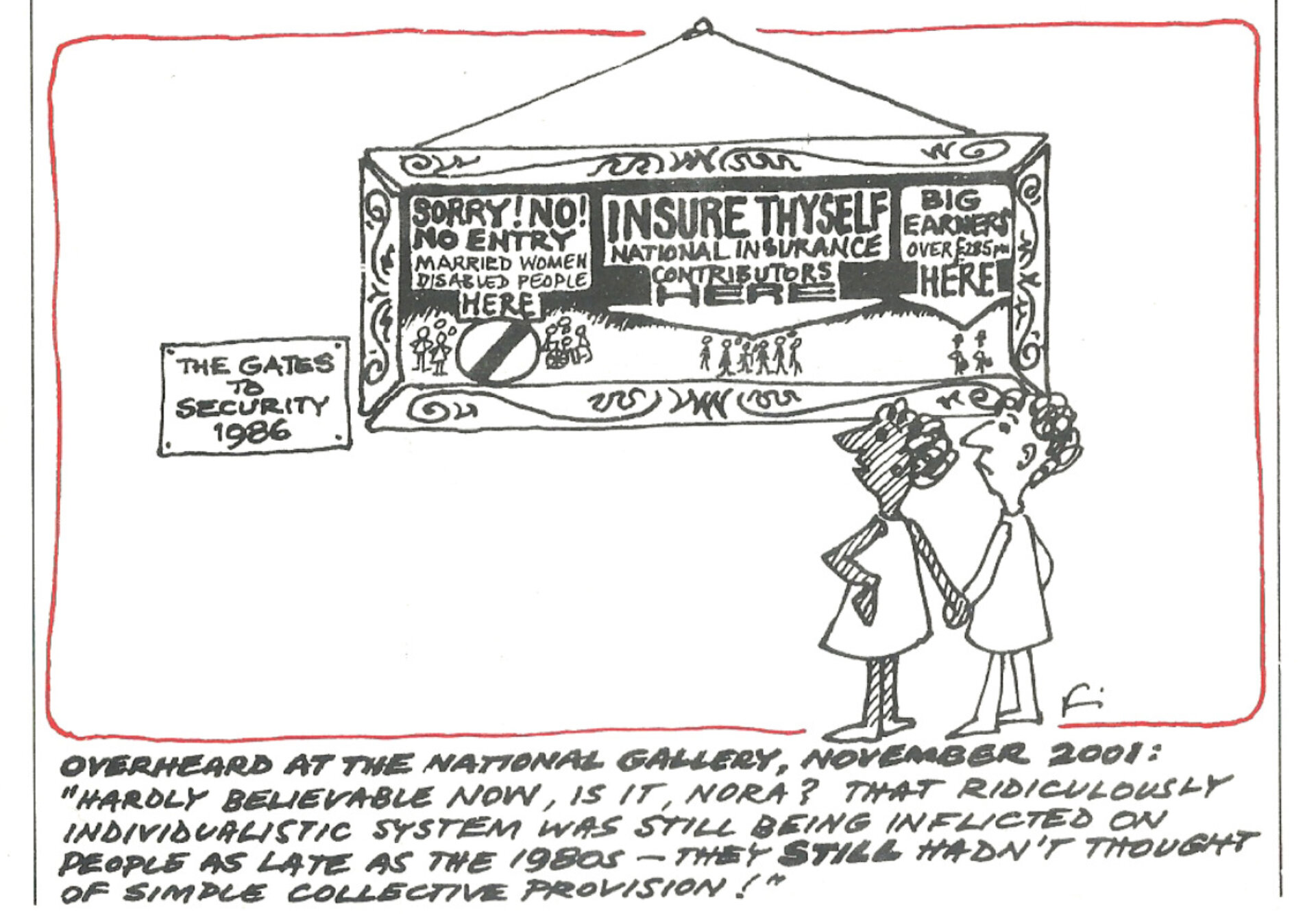

DR: Conditional benefits for the poor have for many years proven to be insufficient at best and mostly catastrophic. Subsidies for the poor in Catalonia itself — the guaranteed citizen income — and the Spanish central government’s minimum living income have been a disaster. The former has been years in the making, the latter was implemented in June 2020 as a response (let’s call it that) to the pandemic-era social situation. Everyone, apart from its designers, has found serious flaws in it. If these are especially bad cases, the problems with conditional subsidies have been known for some time. Poor rollout can make things worse, of course, but the root problem is the design.

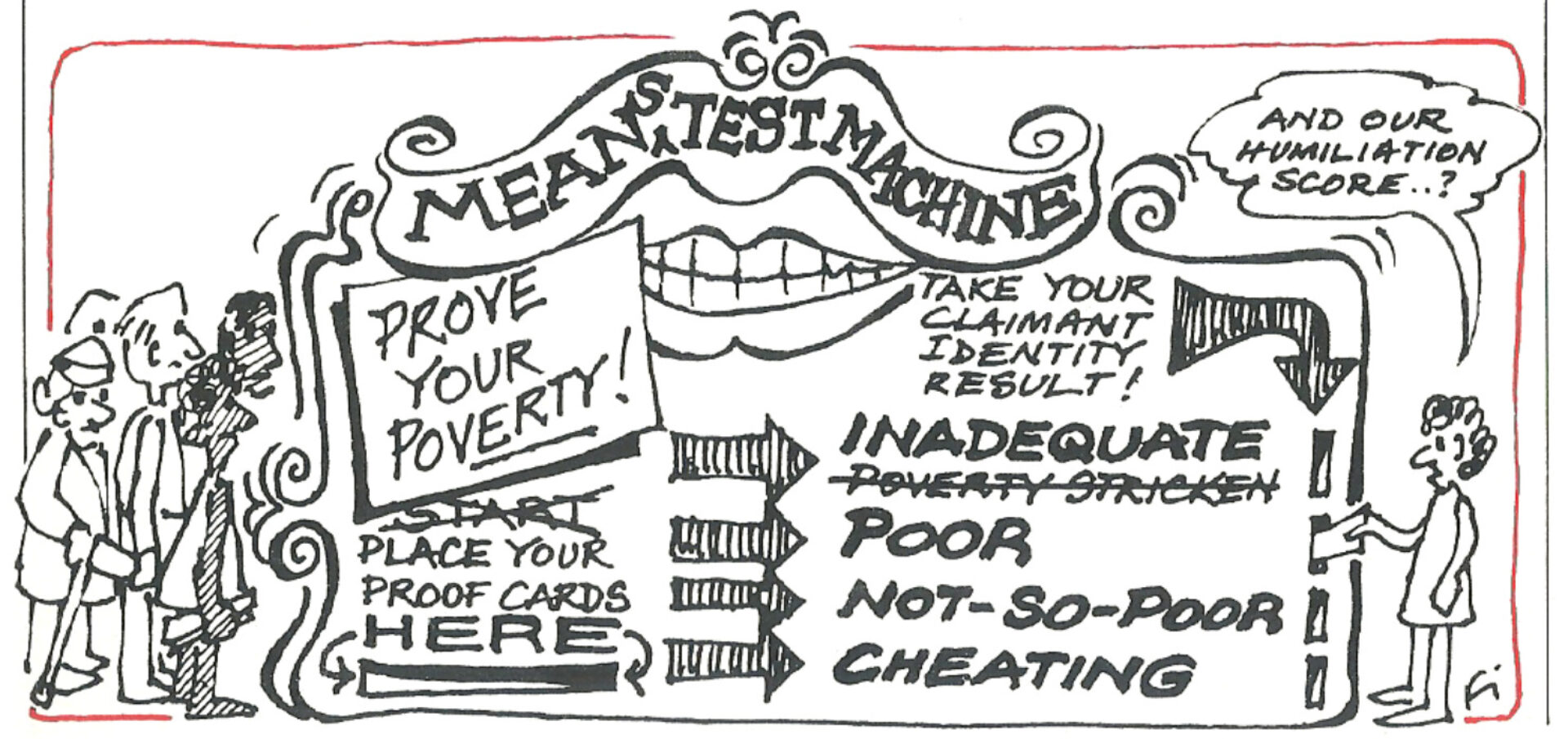

What are the problems with conditional benefits?

They have been known for a long time: the poverty trap, the high administrative and management costs, the stigmatization they involve, the insufficient coverage with respect to the population they ought to cover, and what is known as non-take-up, which is the segment of people who do not apply for a benefit even though they meet all the eligibility requirements and are thus entitled to receive it. In some cases, non-take-up is as high as 60 percent!

The UBI overcomes these problems of conditional benefits — all of them. Perhaps this is one of the reasons why people who’d been opposed to the UBI recognized at the beginning of the pandemic that it ought to be considered.

In the Basque Autonomous Community, which has one of the best subsidies for the poor in the European Union (nothing to do with the minimum living income or benefits anywhere else in Spain), a popular legislative initiative for a UBI has been launched. This is promoted, among others, by people who advise benefits applicants and are thus very knowledgeable about the reality of the subsidies for the poor, here. They are very competent and technically very knowledgeable people. Their conclusion is clear, and this is what they have stated: the Income Guarantee Payment, which is the name given to the Basque regional subsidy for the poor, has failed. Hence their support for UBI.

AF: Feminists have defended, and also criticized, basic income. What are the feminist arguments in favor of UBI?

DR: Well, the arguments offered by feminists are very diverse. At the risk of leaving out some important points, I think we can summarize these as follows. First, UBI would mean greater freedom for women. Already Mary Wollstonecraft pointed out that the attainment of rights, citizenship, and a better status for women, both married and unmarried, required their economic independence. Second, many women today caught in the poverty trap under the system of conditional benefits could escape it with a UBI, thus greatly mitigating the feminization of poverty.

The economic independence that a UBI would allow would make it possible for many women to escape more easily from relationships where there is violence and abuse, as well as to leave paid jobs where sexual harassment or abuse occurs.

Third, with financing that favors the majority of the non-rich population, such as that proposed by Jordi, Lluís, and myself, there is a transfer of money from men to women. This is consistent with what we know about the worse social, labor, and economic conditions that women have on average compared to men.

AF: One of the arguments that you have had to combat most over the years is the idea that it would be better to guarantee full employment than UBI, also because a UBI would discourage job seeking, and even the value of work itself. Why?

DR: Being a supporter of full employment is admirable, almost heroic in today’s conditions, but for me what’s interesting is to make clear whether we are talking about full employment in semi-slavery or in decent conditions. In the Spanish case, it should be remembered that from 1978 to today, this country has been the world champion among the OECD economies for joblessness: the place where the unemployment rate has exceeded 15 percent in thirty years out of forty-two.

There is no doubt that there are parts of society with an employment-centric view, upholding the “dignity of work.” For me, the dignified thing is having a guaranteed material existence.

Many authors, as different in time and intellectual hinterland as Aristotle and Marx, had no doubt that wage labor is “a limited servitude.” Marx spoke of the alienation of wage labor because, he said, as soon as there is no physical or any other kind of coercion, one flees from labor like the plague.

Many think employment has special virtues: the most frequent being a sense of identity and contribution to the community, the dignity it confers, and a structuring of time, among others. A lot of things are mixed up in these statements. Job loss usually leads to terrible situations such as the loss of a home due to the impossibility of paying rent, as well as to serious depression and general deterioration of mental health, even to a sense of loss of identity. There is no doubt about it.

Drawing the conclusion that people are less “happy” than when they did have a job is also defensible. Losing a job due to arbitrary corporate power, to a general or sectoral economic crisis — or for any other reason outside the newly unemployed person’s own will — is not going to make that person happier. That’s obvious, trivial even. But only to this extent can we relate involuntary job loss to unhappiness.

If someone is faced with the choice of having a horrible paying job or a miserable life because of the lack of said job, it is easy to understand why they’d choose the former option.

AF: Has there been resistance from the unions?

DR: A lot. And there still is. There are exceptions and perhaps some cracks are opening up in unions’ monolithism against the UBI. We will see. I have been a member of a union for forty-five years, I have participated in union leadership and work councils for many years in the past, so I think I know this world very well. Over recent decades I’ve seen all sorts of arguments, I think I can summarize them as followed.

It is argued, against UBI, that trade unions would lose strength because it would weaken their potential for collective action — although it is accepted that the UBI increases workers’ individual bargaining power. It is customary to add that the UBI could be used as a pretext to dismantle the welfare state, mainly public education and health care. It has also been argued that employers would exert pressure to reduce wages, since they would argue that part of their salaries would be covered by the UBI. Another argument is that, being a proposal that uncouples material existence from employment and the rights linked to it, UBI is unacceptable for the world of trade unionism — which, after all, makes work central to its worldview.

The UBI — another objection from trade unionists maintains — could numb or appease the working class’s capacity for struggle by assuring it a minimum existence. This would mean that employers could make and unmake their plans with less trouble; this, in turn, would result in greater exploitation of the working class because the passivity that the UBI would bring would end up damaging their wage and social-welfare conditions. Finally, another trade union objection is that what we need to be standing for is full employment: giving people paid work is the right solution because that is what gives us dignity, and all the rest is mere palliatives.

As I have answered this last objection already, I will briefly respond to the various others. The fact that individual bargaining power increases does not mean that collective bargaining power should suffer. In case of a long strike, a UBI could act as a resistance fund: a long strike is very difficult to sustain without a resistance fund because of the significant loss of wages in direct proportion to the number of days on strike.

On the alleged dismantling of the welfare state. The right-wing advocates of the UBI do seek to dismantle the welfare state in exchange for UBI, but the left-wing advocates of the UBI seek a redistribution of income from the richest to the rest of the population and the maintenance, and even the strengthening, of the welfare state. Mixing the very different and opposing ways of defending the UBI of the Right and the Left is perhaps a propagandistic way of confusing the debate, but it has little to do with a rational and sincere discussion.

It’s obvious that employers will bid to try to reduce wages using UBI. Or rather, they’ll seek to do that whether or not UBI is there. But that is part of what in times past was called, and in today’s times should be called, class struggle.

AF: In Jacobin Michal Rozworski asked what the ultimate point of UBI was. I pass his question over to you: if there were a social movement broad and strong enough to implement an UBI, wouldn’t it make more sense to make much more ambitious demands?

DR: The UBI is not a socialist program, nor is it a whole economic policy. In the face of any proposal for improvement, one can always say that it is insufficient and that it does not put an end to capitalism, for example. Or that it is possible to go further. That is irrefutable.

But let me make a general comment.

The UBI is a reform of the currently existing capitalism, it is not a measure that would do away with it.

A capitalism like the present one, with a UBI, would undoubtedly still be capitalism, but it would be a capitalism notably different from the capitalism we know today.

With the Fordist pact the working classes gave up control over production in favor of ex-post, conditional measures. They did that in a capitalism very different from today’s. I think that the UBI would allow the working class and the vast majority of women to significantly increase their bargaining power. Because by unconditionally guaranteeing people’s social existence, a UBI would enable the ability to “say no” to crappy jobs. For those who stand for freedom, this increase in bargaining power is something that alone deserves to be defended.

______________________________________________________

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Daniel Raventós is a professor at the Faculty of Economics and Business at the University of Barcelona.

ABOUT THE INTERVIEWER: Àngel Ferrero is a journalist and translator, and a regular contributor to Público, El Salto, and Catarsi magazine.

The post Basic Income Will Increase Workers’ Bargaining Power appeared first on Basic Income Today.

This post was originally published on Basic Income Today.