By Ty Rushing

See original post here.

As the Iowa Senate debated earlier this year a bill to ban local governments from providing direct financial assistance to residents, Sen. Tony Bisignano called out the hypocrisy on display by many of his Republican colleagues who supported the legislation even as they receive direct payments from the federal government.

“This body, a great deal of members in this body live off of subsidy or depend on it annually,” said Bisignano, a Democrat who represents the southeast side of Des Moines. “This study’s been going on since the ’30s—farm subsidy—and it was there to stabilize the farm economy, to stabilize farming to keep the farmers able to farm.”

Starting Line dug into the data and Bisignano is correct: About a fourth of the 150-person Iowa Legislature benefits from some form of farm subsidies.

House Speaker Pat Grassley has received $65,102 directly while his father, Robin, has received a little more than $1.4 million. Sen. Jeff Edler only received $1,180 in his name, but his family farming operation has received $2.5 million since 1995.

These sums are available thanks to the efforts of the Environmental Working Group (EWG), a Washington, DC-based nonprofit that works “tirelessly to reform our nation’s broken chemical safety and agricultural laws.”

One of the ways EWG does that is by tracking and maintaining a database of farm subsidy recipients. EWG files an annual Freedom of Information Act request with the US Department of Agriculture and uses those records to compile a farm subsidy database that features every individual recipient or individual entity.

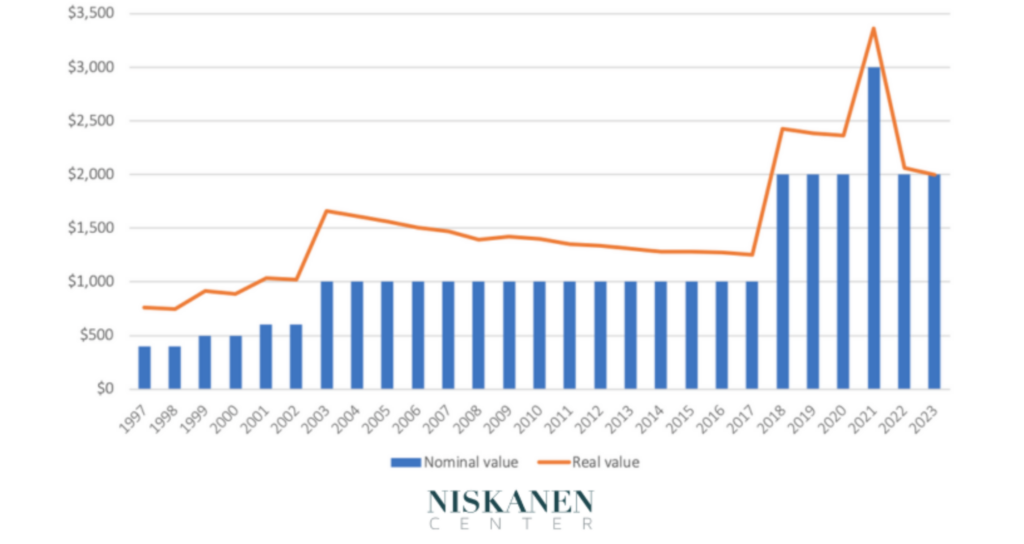

History of subsidies

As Bisignano noted, farm subsidies started during the Dust Bowl and the Great Depression and the programs have not changed much nearly a century later. However, what has changed is the size of the farms, according to EWG Midwest Director Anne Schechinger.

“Really now, the programs are benefiting the largest, wealthiest farms,” she said. “They are based on the acres you have or the amount of crops you produce. There were a lot of farms that were of the same size back in the 1930s and now there are these huge farms and a lot of very small farms as well.”

In 1930, Iowa had 214,928 farms and the average farm size was 158.3 acres, according to the US AG Census. By 2022, the number of farms has dwindled to 86,911, while the average farm size has more than doubled, growing to 345 acres.

According to EWG, from 1995-2023 Iowa received $42.4 billion in federal subsidies, which amounts to 8.1% of all farm subsidies in that period. Iowa only trailed Texas in total federal subsidies received for that duration.

“Iowa’s always close to the top because of the nature of the state having so much agriculture and the fact that so much of the agriculture is corn and soybeans because all of these subsidy programs are designed to benefit commodity farmers,” Schechinger said.

“People growing fruits and vegetables and nuts in California don’t benefit nearly as much from farm subsidy programs as commodity growers in the Midwest.”

Who directly benefits from farm subsidies?

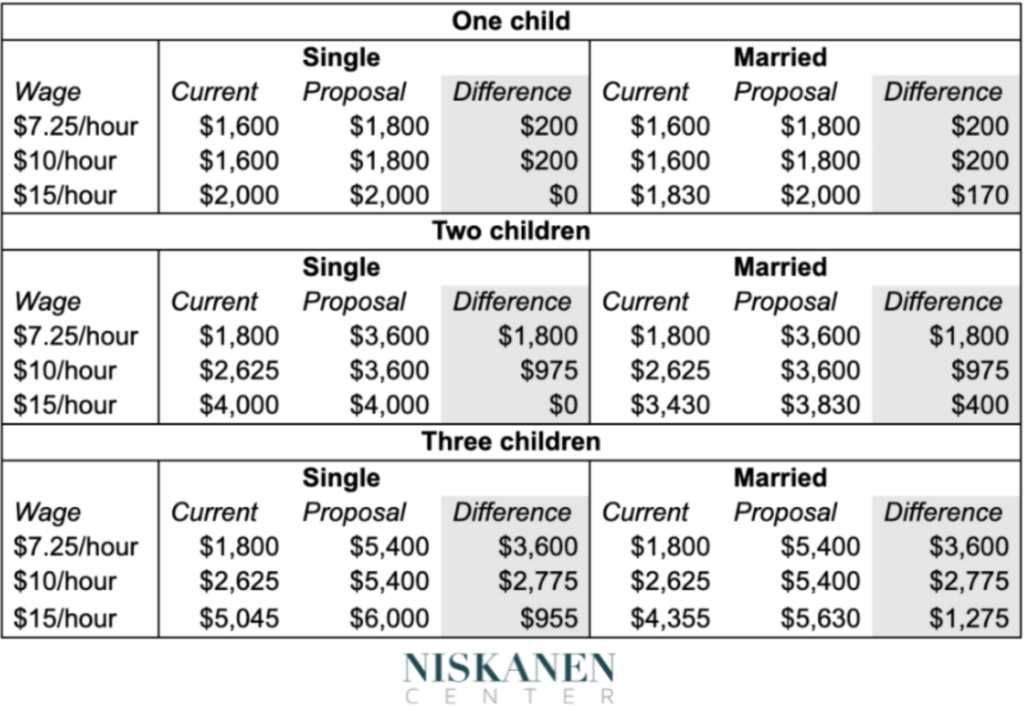

If an individual makes less than $900,000 a year, they can still qualify for most farm subsidies. For couples, it’s $1.8 million. Furthermore, crop insurance subsidies have no income limit.

“Basically, millionaire farmers can qualify for subsidies,” Schechinger said. “We like to make that dichotomy when we’re talking about SNAP [Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program] because think of the income to qualify for food stamps versus farm subsidies.”

Something else unique about farm subsidy programs is one farm can qualify for an unlimited number of subsidy recipients. In Iowa for example, Sen. Dan Zumbach has received $1.2 million in farm subsidies and five other people/businesses registered to his farm have collectively received close to a million dollars in subsidies.

“You can qualify for payments if you are the son or daughter of the person who owns the farm if you are over 18—you have to be an adult,” said Schechinger, who noted that the 2018 Farm Bill extended this provision to cousins, nieces, and nephews of farmers and farm landowners.

“So we end up seeing a lot of payments going to people who live in the same household,” she continued. “There’s also a lot of farmer partnerships. Basically, large family farms, but you can have an unlimited number of people on those.”

Basic income in Iowa

Members of the Iowa Legislature worked to ban programs like UpLift — The Central Iowa Basic Income Program, which receives no state funds, while personally benefiting from subsidies.

UpLift is a poverty-reduction research pilot program to see how receiving an additional $500 with no restrictions will affect 110 recipients’ lives. The program covers residents in Dallas, Polk, and Warren counties. It is funded via a public-private partnership and supporters include Bank of America, Polk County, Principal, Wells Fargo, and the cities of Des Moines, Windsor Heights, and Urbandale.

While UpLift will be able to complete its study by 2026, no future programs like it can be established unless HF 2319—which Gov. Kim Reynolds signed into law on May 1—is repealed by a future legislature and governor.

During the Senate debate, Bisignano was quickly shut down when he pulled out a list and began to read the names of Iowa lawmakers who received farm subsidies or have relatives who have received them.

“I’m just going to do some last names to show you what a stipend is—what socialism is—what subsidy is all about,” Bisignano said. “Might as well as start with the Grassleys—I don’t know which one—but it’s $1.3 million in subsidies from ’95 to 2021.”

Bisignano told Starting Line he disposed of his notes following the legislative session; however, Starting Line ran the names of every Iowa state representative and Iowa state senator through the EWG 1995-2023 Iowa subsidy database to verify his claims.

Using EWG data, Starting Line determined that 14 out of 50 Iowa senators and 24 out of 100 house representatives either directly received subsidies or had a close relative (spouse, grandparent, aunt/uncle, sibling, or in-law) who received federal subsidies.

Starting Line also found instances where a farm address used by a legislator was connected to multiple other people or businesses.

To verify these ties to legislators, Starting Line used a combination of obituaries, state business registrations, court documents, property records, social media, the Iowa Official Register 2023-2024 book, and more to confirm direct recipients or familial relationships.

Below, we will list the members of the Iowa Legislature and/or their family members or business partners who received farm subsidies between 1995-2023 and how they voted on the bill to ban local government basic income programs:

Iowa Senate

Sen. Waylon Brown (R-Osage): $12,708 to Waylon Brown in Worth County and $18,854 to Waylon Brown in Mitchell County. Sen. Brown voted to ban local government basic income programs.

Sen. Mark Costello (R-Imogene): $364,369 to Mark Costello in Mills County and $664,172 to Lynn Costello Inc.—the business is registered to the same address and Costello is listed as the company’s president, treasurer, and secretary in Iowa Secretary of State business filings—in Freemont and Mills County. Sen. Costello voted to ban local government basic income programs.

Sen. Adrian Dickey (R-Packwood): $3,294 to Adrian Dickey in Jefferson County; $767,710 to Dickey Inc. (owned by multiple family members, including Adrian’s father, Dave) in Jefferson County; $7,161 to the Harold Dickey Trust (Adrian’s late grandfather) in Jefferson County; and $52,504 to the Caroline Dickey Trust (Adrian’s late grandmother) in Jefferson County. Sen. Dickey voted to ban local government basic income programs.

Sen. Dawn Driscoll (R-Williamsburg): $101,381 to C. Elliot Driscoll (Dawn’s late father-in-law) in Iowa County; $172,374 to Erle Driscoll (Dawn’s uncle by marriage) in Iowa County; $35,508 to Joseph Driscoll in Iowa County, Iowa, and Henry County, Illinois, and $277,748 to Walridge Conventional Hamp AKA Driscoll Farms in Iowa County, Iowa. Sen. Driscoll voted to ban local government basic income programs.

Sen. Jeff Edler (R-State Center): $1,180 to Jeffrey “Jeff” Edler in Marshall County; $2,500,207 to JJJ Elder Partnership/JJJ Farms (registered to same address as Jeff Edler) in Marshall, Story, and Wayne counties; and $1,180 to Jed Edler (Jeff’s brother) in Marshall County. Sen. Edler voted to ban local government basic income programs.

Sen. Julian Garrett (R-Indianola): $283,154 to Julian Garrett in Clarke and Warren counties in Iowa, and Harrison County, Missouri.

Sen. Jesse Green (R-Boone): $10,647 to Jesse Green in Webster County, $161,567 to Jesse Green Farms Inc. in Webster County; $141,053 to Viola C. Green (same address listed for previous entries); $129,938 to Frank Green (Jesse’s father) in Webster County; $1,449,894 to Frank Green Farms Inc. in Webster County; $7,608 to FS&J Livestock Co. (owned by Frank Green) in Webster County; and $30,862 to Viola Green Estate (registered to Frank’s address). Sen. Green voted to ban local government basic income programs.

Sen. Kerry Gruenhagen (R-Walcott): $65,289 to Kerry Gruenhagen in Muscatine County and $1,302,747 to Ron Gruenhagen in Muscatine and Scott counties (Kerry’s father). Sen. Gurenhagen voted to ban local government basic income programs.

Sen. Dennis Guth (R-Klemme): $648,579 to Guth Farms Inc. in Hancock County and $19,189 to Dennis Guth in Hancock County. Sen. Guth voted to ban local government basic income programs.

Sen. Ken Rozenboom (R-Pella): $14,664 to Ken Rozenboom in Mahaska County; $172,905 to Calvin Rozenboom (Ken’s brother) in Mahaska County and $382,612 to Country Lane Park Inc. also in Mahaska County (same address listed for Calvin Rozenboom). Sen. Rozenboom voted to ban local government basic income programs.

Sen. Jason Schultz (R-Schlewsig): $158,571 to Jason Schultz in Crawford County. Sen. Schultz voted to ban local government basic income programs.

Sen. Tom Shipley (R-Nodaway): $24,894 to Tom Shipley in Adams County. Sen. Shipley voted to ban local government basic income programs.

Sen. Annette Sweeney (R-Iowa Falls): $447,390 to David Sweeney (Annette’s husband) in Hardin County, and $8,325 to the David Sweeny Trust (listed at the same address) in Hardin County, and $21,033 to Cynthia Ioerger (Annette’s sister) in Hardin County. Sen. Sweeney voted to ban local government basic income programs.

Sen. Dan Zumbach (R-Ryan): $1,208,071 to Daniel Zumbach in Delaware and Linn counties; $424,406 to Earl and Edna Zumbach Revocable Trust (Dan’s parents); in Buchanan and Delaware counties; $496,179 to Charles G. Ward (registered to Dan’s address) in Benton, Buchanan, Delaware, and Linn counties; $356,578 to Country Hill Farm LLC (registered to Dan’s address) in Buchanan and Delaware counties; $73,244 to Shelldan Farms LLC (registered to Dan’s address) in Delaware and Linn counties; $24,962 to Pac Land LLC (registered at Dan’s address) in Buchanan County.

Iowa House

Rep. Jane Bloomingdale (R-Northwood): $995,865 to James Bloomingdale (her husband) in Worth County. Rep. Bloomingdale voted against banning local government basic income programs.

Rep. Ken Carlson (R-Onawa): $569,241 to Ken Carlson in Monona County, $119,946 to Katherine Alice Carlson Willey (his late mother) at the same Monona County address. Rep. Carlson voted to ban local government basic income programs.

Rep. Taylor Collins (R-Mediapolis): $5,372 to John McCulley Sr. Revocable Trust (his great grandpa) in Louisa County; $71,620 to John McCulley Jr. (his great uncle) in Des Moines County; $993,775 to Oak Research Farms Inc. (same address listed for John McCulley Jr., who serves as secretary for the corporation, and Taylor Collins’ great uncle Mark is the president) in Des Moines and Louisa counties; $293,422 to Tren Corp (owned by Taylor Collins’ grandparents, Robert and Denise McCulley) in Des Moines and Louisa counties; $183,965 to Mark McCulley (great uncle) in Des Moines and Louisa County. Rep. Collins voted to ban local government basic income programs.

Rep. Tom Determann (R-Camanche): $90,510 to Jay Determman (Tom’s late brother) in Clinton County, $860 to the Jay Determann Estate in Clinton County, $85,795 to Cory Determann (Tom’s brother and Jay’s son) in Clinton County. Rep. Determan voted to ban local government basic income programs.

Rep. David Deyoe (R-Nevada): $108,994 to David Deyoe in Story County and $1,369 to Billy Deyoe (David’s later father) in Story County. Rep. Deyoe voted to ban local government basic income programs.

Rep. Tracy Ehlert (D-Cedar Rapids): $542,779 to Steve Ehlert (Tracy’s father-in-law) in Linn County. Rep. Elhert voted against banning local government basic income programs.

Rep. Dean Fisher (R-Montour): $33,103 to Dean Fisher in Tama County, $39,776 to Gerald Fisher (Dean’s later father) in Tama County; and $16,075 to Mary Etta Fisher (Dean’s late mother) in Tama County. Rep. Fisher voted to ban local government basic income programs.

Rep. John Forbes (D-Urbandale): $9,267 to John Forbes in Tama County. Rep. Forbes voted against banning local government basic income programs.

Rep. Thomas Gerhold (R-Atkins): $501,312 to Carl Gerhold (Thomas’ brother) in Benton and Linn counties, $72,369 to Daniel Gerhold (Thomas’ nephew) in Benton and Linn counties, $80 to Melissa Gerhold (Thomas’ niece) in Benton County. Rep. Gerhold voted to ban local government basic income programs.

House Speaker Pat Grassley (R-New Hartford): $65,102 to Patrick Grassley in Butler County; $1,448,143 to Robin Grassley (Pat’s father) of Butler County. Speaker Grassley voted to ban basic local government income programs.

Rep. Austin Harris (R-Moulton): $954,770 to Rex Harris (Austin’s father) in Appanose, Davis, and Wayne counties in Iowa, and Putnam County in Missouri. Rep. Harris voted against banning local government basic income programs.

Rep. Heather Hora (R-Washington): $596,582 to HK Farms Inc. (owned by Hora and her husband, Kurt) in Washington County, $81,789 to Kurt Hora in Washington County. Rep. Hora voted to ban local government basic income programs.

Rep. Chad Ingles (R-Randalia): $257,649 to Chad Ingles in Fayette County, $476,447 to James Ingles (Chad’s late father) of Fayette County. Rep Ingels voted against banning basic local government income programs.

Rep. Thomas Jeneary (R-Le Mars): $228 to Thomas Jeneary in Allamakee County. Rep. Jeneary voted to ban local government basic income programs.

Rep. Megan Jones (R-Sioux Rapids): $785,012 to William Jones (Megan’s husband) of Clay County, $124,413 to Jones Farms Inc. (registered to previous address) in Clay County, $113,943 to Jones Land And Cattle (owned by Megan’s father-in-law, Curtis Jones). Rep. Jones voted to ban local government basic income programs.

Rep. Bobby Kaufmann (R-Wilton): $9,402 to Robert “Bobby” Kaufmann in Cedar County, $9.639 to Jeffrey “Jeff’ Kaufmann (Bobby’s father) in Cedar County. Rep. Kaufmann did not vote on the bill to ban local government basic income programs.

Rep. Shannon Latham (R-Sheffield): $27,201 to Willard Latham (Shannon’s late father-in-law) in Kossuth County, $16,595 to the William J Lathan Irrevocable Trust in Kossuth County, and $26,840 to Linda Latham (Shannon’s mother-in-law) in Kossuth County. Rep. Latham voted to ban local government basic income programs.

Rep. Gary Mohr (R-Bettendorf): $41,549 to Gary Mohr in Pottawattamie County. Rep. Mohr voted to ban local government basic income programs.

Rep. Norlin Mommsen (R-De Witt): $126,148 to Norlin Mommsen in Clinton County. Rep. Mommsen voted to ban local government basic income programs.

Rep. Anne Osmundson (R-Volga): $412,936 to Steve Osmundson (Anne’s husband) in Clayton and Fayette counties. Rep. Osmundson did not vote on the bill to ban local government basic income programs.

Rep. Mike Sexton (R-Rockwell City): $336,521 to Michael Sexton in Calhoun County, $417,788 to Verle Sexton (Mike’s late father) in Calhoun County, $343,633 to Dale Sexton (Mike’s late uncle) in Calhoun County, and $77,945 to Mary Sexton (Dale’s wife and Mike’s aunt) of Calhoun County. Rep. Sexton voted to ban local government basic income programs

Rep. David Sieck (R-Glenwood): $1,122,896 to David A. Sieck in Adair, Cass, Clarke, Fremont, Mills, Page, and Warren counties in Iowa; Finney County, Kansas; and Nodaway County, Missouri. Rep. Sieck voted to ban local government basic income programs.

Rep. Devon Wood (R-New Market): $423,940 to Daniel Gordon Wood (Devon’s father) in Page and Taylor counties. Rep. Wood voted to ban local government basic income programs.

Rep. Derek Wulf (R-Hudson): $230,286 to Derek N. Wulf in Black Hawk County; $1,319,019 to Shallow Creek Lane and Livestock LLC (owned by Derek Wulf) in Black Hawk County, $299,926 to Double D’s (registered to Derek Wulf’s address), and $140,739 to Duane Wulf (Derek’s father) in Benton and Black Hawk counties. Rep. Wulf voted to ban local government basic income programs.

This post was originally published on Basic Income Today.