This content originally appeared on The Grayzone and was authored by The Grayzone.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on The Grayzone and was authored by The Grayzone.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

President-elect Trump, himself found liable in court for sexual abuse, has picked a striking number of suspected sexual predators for key positions in his incoming administration. Trump’s early pick of former Florida Congressmember Matt Gaetz for attorney general was shot down amid a firestorm over sexual misconduct allegations. Now Trump is pushing hard to keep the rest of his picks on track, including Fox host Pete Hegseth for defense secretary and Robert F. Kennedy Jr. for health and human services secretary. Hegseth paid an undisclosed amount to a woman who accused him of sexual assault. Meanwhile, a woman who worked for RFK Jr. as a babysitter accused him of sexual assault at his home in 1998. Even one of the few women Trump has chosen, professional wrestling mogul Linda McMahon for education secretary, was sued for allegedly ignoring complaints that a WWE ringside announcer sexually abused children for years. “Trump really is the embodiment of a male entitlement,” says Deborah Tuerkheimer, professor of law at Northwestern University. Tuerkheimer says the president and these Cabinet picks are a bellwether for how society responds to abuse. “The #MeToo movement was about and continues to be about not just individual allegations, but this larger question of who’s held accountable and what kind of cultural toleration do we have for abuse by powerful men.”

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty and was authored by Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on The Progressive — A voice for peace, social justice, and the common good and was authored by Mike Ervin.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on The Intercept and was authored by The Intercept.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on VICE News and was authored by VICE News.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by Radio Free Asia.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by Radio Free Asia.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on The Real News Network and was authored by The Real News Network.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Human Rights Watch and was authored by Human Rights Watch.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Floating cages with fish by the thousands may be popping in the Gulf of Mexico under a controversial plan that was backed by President-elect Donald Trump’s administration four years ago and is likely to gain traction again after Trump begins his second term next month.

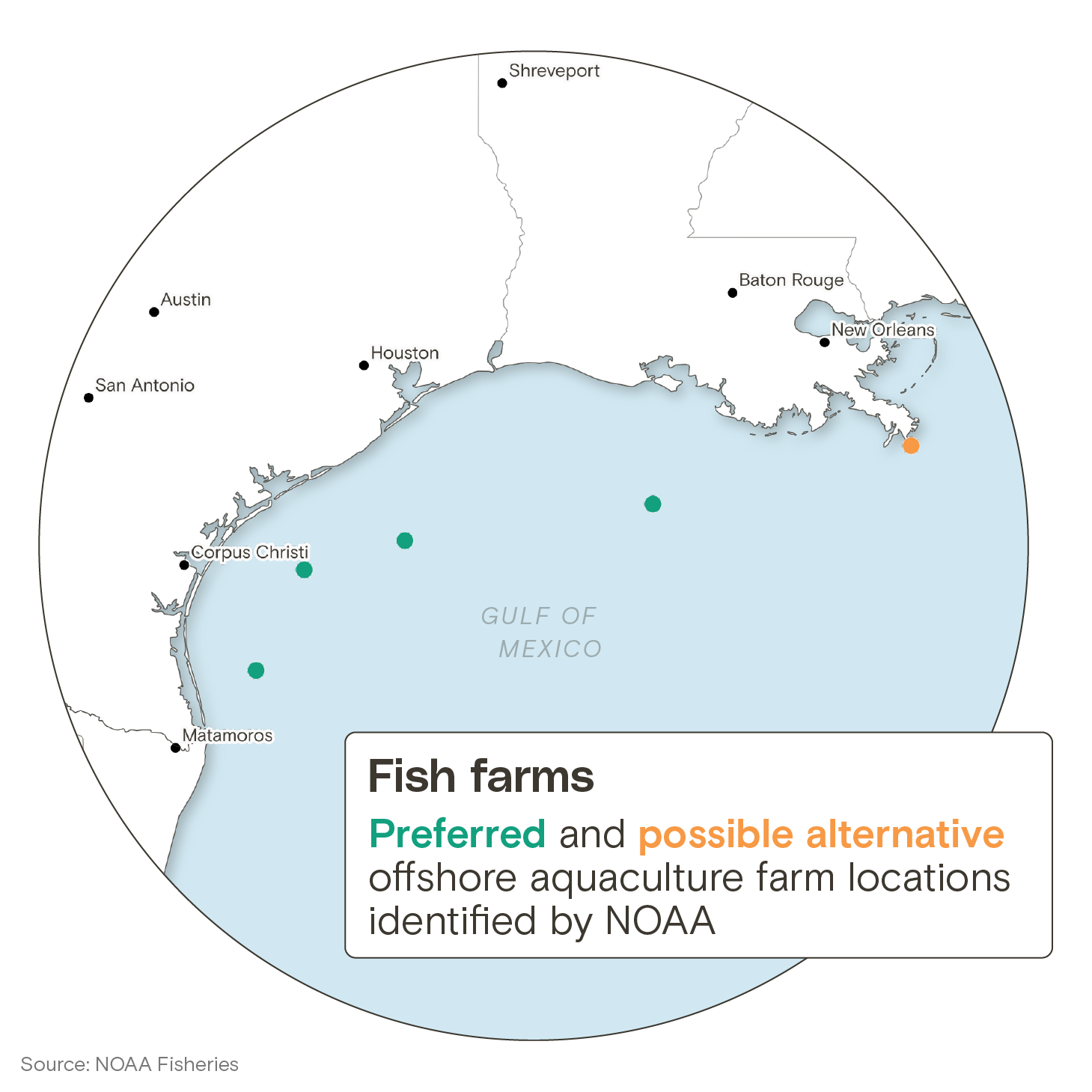

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration recently identified five areas in the Gulf that the agency says strike a balance between the needs of the growing aquaculture industry and the potential impacts on the marine environment and elements of the seafood industry that depend on wild fisheries.

Identifying these “aquaculture opportunity areas” is part of a decade-long federal plan to open the Gulf and other offshore areas to aquaculture. The plan got a strong push from Trump but slowed under President Joe Biden’s administration, which concludes next month.

Three of NOAA’s preferred aquaculture areas are off the coast of Texas and one is south of Louisiana. Each area ranges from 500 to 2,000 acres and could total 6,500 acres. A fifth area, considered a possible alternative, has been identified near the mouth of the Mississippi River, but it would likely conflict with shipping traffic and shrimping in that area.

The areas would open the Gulf for the first time to the large-scale cultivation of shellfish, finfish and seaweed. Seafood companies have long expressed interest in raising large, high-value species, including redfish and amberjack, in floating net pens several miles off the coasts of Louisiana, Texas and Florida.

Opponents say fish poop, fish feed and other organic debris that often swirls around offshore aquaculture operations will worsen the Gulf’s massive “dead zone,” a New Jersey-size area of low oxygen that pushes away fish and suffocates slow-moving crabs and other shellfish. Fish that escape from floating farms can spread diseases and parasites, gobble up food that supports other species, and potentially mate with their wild counterparts, introducing their domesticated genes, which tend to produce slower, dumber fish.

“When you think of all of these environmental impacts, it’s pretty concerning,” said Marianne Cufone, executive director of the New Orleans-based Recirculating Farms Coalition, a group opposed to offshore aquaculture. “Plus, we get super violent storms in the Gulf of Mexico. I don’t know how these (farms) won’t be damaged with fish escaping.”

But the planet’s already-taxed wild fish stocks can’t meet the world’s expanding appetite for seafood alone, said Neil Anthony Sims, CEO of Ocean Era, an aquaculture company that hopes to develop a floating redfish farm 40 miles from Sarasota, Florida. His assertion is backed by a 2021 Stanford University study that predicted global fish consumption is likely to increase by 80 percent over the next 25 years.

“We can’t feed a planet with wild fish anymore than we could feed a planet with wild antelope,” Sims said.

Many fish, including tilapia and catfish, are raised in ponds and other land-based facilities. Floating fish farms in state-managed waters are increasingly rare. In 2022, Washington state effectively banned its once-thriving salmon farming industry after about 260,000 non-native Atlantic salmon escaped from a net pen north of Puget Sound. Hawaii still hosts a floating fish farm that raises Hawaiian kampachi, a fish related to amberjack.

Deeper waters managed by the federal government have remained aquaculture-free.

Like Trump, Biden backs opening federal waters to fish farming, but his administration has taken a more methodical approach, directing NOAA to study various areas that may be “environmentally, socially and economically viable” for supporting offshore aquaculture.

Trump was more forceful during his first term, signing an executive order in 2020 that was aimed at breaking through the regulatory barriers that have long impeded fish farming in federal waters. The Trump administration backed offshore aquaculture as a way to create jobs, broaden markets for U.S. companies and help meet growing demand for seafood.

A 2020 federal appeals court ruling blocked new regulations allowing offshore fish farming under the Magnuson-Stevens Act, the primary law governing fisheries since 1976. But other laws, including the National Aquaculture Act of 1980 and the Fish and Wildlife Coordination Act of 1980, give NOAA the authority to develop aquaculture opportunity areas and conduct environmental impact permitting for offshore farms.

The opportunity areas unveiled by NOAA last month set the stage for a final greenlight by Trump or Congress. The public can comment on the opportunity areas until Feb. 20. NOAA will host the first of three virtual meetings to gather feedback on the areas on Dec. 17.

NOAA is also considering aquaculture opportunity areas in Southern California, but opposition is likely to be stiffer there than in the Gulf, where residents are already accustomed to heavily industrialized coastal waters, with thousands of offshore oil and gas structures near Louisiana and Texas and pipelines crisscrossing the seafloor.

But adding more industrial infrastructure will further crowd the Gulf’s first industry: fishing.

“We’re already dealing with the rigs and oil wells and all kinds of debris,” said Acy Cooper, president of the Louisiana Shrimp Association. “And you want to put more out there? It’ll be our downfall.”

The Gulf’s shrimping industry has been losing ground to imported shrimp, which is typically raised in farms in Asia and South America and is far cheaper than the wild-caught varieties.

Cooper, a third-generation shrimper in Plaquemines Parish, said America’s desire for seafood should be met by fishers rather than farmers.

“If you want fish, there’s a lot of fishermen here for you. We ready,” he said.

But NOAA isn’t so sure the U.S.’s wild fisheries can support the demand for seafood alone. About 80% of the seafood consumed in the U.S. is imported, and about half of the imports are produced via foreign aquaculture. That’s giving rise to a “seafood trade deficit” that had grown to $17 billion in 2020, according to NOAA.

As much as U.S. fishers may want to meet demand, wild stocks are under increasing threat by climate change, which is altering marine species reproduction, feeding habits and distribution.

Offshore fish farming can help the U.S. adapt by producing seafood in a more controlled environment, according to NOAA.

“Aquaculture offers a pathway to grow climate resilience,” said Janet Coit, NOAA Fisheries’ assistant administrator. “Identifying areas suitable for sustainable aquaculture is a forward-looking step toward climate-smart food systems.”

But fish farms will likely worsen the dead zone, one of the Gulf’s main climate-related problems. The dead zone is fueled by agricultural runoff and other nutrient pollution that flushes into the Gulf from the Mississippi. Rising temperatures speed the growth of algae that feeds on the nutrients. When the massive algal blooms die, their decomposition robs the Gulf of oxygen.

Developing floating farms in and around the dead zone will add even more nutrients from poop and fish food that will nourish bigger blooms, Cufone said.

“We have warmer waters and all of the difficulties our fisheries are having because of climate change, but none of that supports an argument for factory fish farms,” she said. “If we care about climate change, we shouldn’t have them in our oceans.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline How Trump could bring fish farms to the Gulf of Mexico on Dec 11, 2024.

This content originally appeared on Grist and was authored by Tristan Baurick.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by Radio Free Asia.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by Radio Free Asia.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Comprehensive coverage of the day’s news with a focus on war and peace; social, environmental and economic justice.

The post The Pacifica Evening News, Weekdays – December 10, 2024 President-elect Trump calls for members of the House Select Committee investigating January 6 to be jailed. appeared first on KPFA.

This content originally appeared on KPFA – The Pacifica Evening News, Weekdays and was authored by KPFA.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on The Intercept and was authored by The Intercept.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on The Grayzone and was authored by The Grayzone.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on VICE News and was authored by VICE News.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

A secret deal between the US and China announced in November allowed Chinese nationals to be freed in exchange for the release of several Americans imprisoned in China.

One of the Chinese nationals who was freed, Xu Yanjun, had been serving a 20-year sentence. He had worked for China’s Ministry of State Security. One of the Americans in China, John Leung, reportedly an FBI informant, had been held in prison for three years. Two other Americans, Kai Li, also accused of providing information to the F.B.I., and Mark Swidan, a Texas businessman, were freed at the same time. In addition, Ayshem Mamut, the mother of human-rights activist Nury Turkel, and the two other Uyghurs were allowed to leave China. They all traveled on the same plane to the United States.

Holden Triplett, the co-founder of a risk-management consultancy, Trenchcoat Advisors, has served as the head of the FBI office in Beijing and as director of counterintelligence at the National Security Council. Here, he weighs in on the high-stakes game of exchanging spies. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

RFA: Spy swaps have a long history. What was it like in the past?

Holden Triplett: During the Cold War, there were a lot of spy swaps. It’s kind of a normal way of interacting between two rival powers. But it was always Russia, or the Soviet Union, and the United States. It’s not something that China had typically engaged in in the past.

RFA: Why would China, or any country, be interested in a spy swap?

Holden Triplett: China would be very interested in getting back the individuals who’d worked for them. The longer they’re in prison in the U.S., the more chance they’re going to divulge information about what they’ve done. Also, the Chinese want to be able to say to the people who work for them, ‘Hey, we may put you in dangerous situations. But, don’t worry, if anything happens, we’ll get you back home.’ The down side for the Chinese, of course, is that it’s an implicit acknowledgement of what they’ve been doing. In the past, they’ve denied that they’re [engaged in espionage].

RFA: And for the U.S?

Holden Triplett: The idea is the same; We get our spies back. It’s more of a game, I guess you could say. There’s a bit more protection for spies than for others. They get arrested, but they don’t serve time. And so, spying on each other is made into a regularized affair.

My concern is that the Chinese say, ‘Now that we’ve established this kind of exchange, people for people, now all we need to know to do now is pick up some more Americans and arrest them.’ Then, the Chinese can try and bargain with the U.S. for their release.

We’ve already seen that in Russia with Brittney Griner [an American basketball player who was imprisoned in Russia]. Look at who the Russians got back – Viktor Bout [a Russian arms dealer found guilty of conspiring to kill Americans].

The Russians have wanted him for decades. Nothing against Ms. Griner, but that is a pretty easy decision-making process. They pick up somebody who has star power, and they can get someone they want back. If China’s gotten that message, then Americans should be concerned about going to China. They could become a chip in a larger geopolitical game. There’s a possibility that they could get arrested and end up in a nightmare jail.

RFA: Well, they say you’re not supposed to negotiate with –

Holden Triplett: – with terrorists. Look, I think the U.S. is in a really difficult place. There’s pressure on the U.S. government from the families to get them back.

RFA: Several Uyghurs were also released. What is the significance of that?

Holden Triplett: I would assume the Chinese got something for this. They’re very transactional. They’re not doing something for the good of the relationship between the U.S. and China.

RFA: It didn’t seem as though John Leung, who’d been held in a Chinese prisoner, was an important asset for the FBI. What do you think was behind this?

Holden Triplett: I don’t know what role he played for the FBI, or even if that’s true. But regardless, the message from the bureau is: Don’t worry. Even if you’re doing dangerous work, we will protect you. We will come and get you.

Edited by Jim Snyder.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by Tara McKelvey.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on The Real News Network and was authored by The Real News Network.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on The Intercept and was authored by The Intercept.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by Radio Free Asia.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Comprehensive coverage of the day’s news with a focus on war and peace; social, environmental and economic justice.

The post The Pacifica Evening News, Weekdays – December 6, 2024 appeared first on KPFA.

This content originally appeared on KPFA – The Pacifica Evening News, Weekdays and was authored by KPFA.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on The Grayzone and was authored by The Grayzone.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on The Intercept and was authored by The Intercept.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on The Intercept and was authored by The Intercept.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on The Intercept and was authored by The Intercept.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.