This content originally appeared on Playing For Change and was authored by Playing For Change.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on The Grayzone and was authored by The Grayzone.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by Radio Free Asia.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Comprehensive coverage of the day’s news with a focus on war and peace; social, environmental and economic justice.

The post The Pacifica Evening News, Weekdays – July 5, 2024 Biden campaigns in Wisconsin, defiantly vows to stay in the race and win. appeared first on KPFA.

This content originally appeared on KPFA – The Pacifica Evening News, Weekdays and was authored by KPFA.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on The Real News Network and was authored by The Real News Network.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

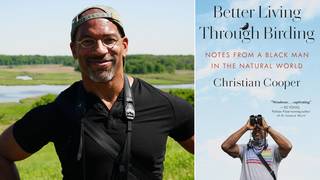

We continue our July 5 special broadcast by revisiting our recent conversation with Christian Cooper, author of Better Living Through Birding: Notes from a Black Man in the Natural World and host of the Emmy Award-winning show Extraordinary Birder. We spoke with Cooper after New York City’s chapter of the Audubon Society officially changed its name to the New York City Bird Alliance as part of an effort to distance itself from its former namesake John James Audubon, the so-called founding father of American birding. The 19th century naturalist enslaved at least nine people and espoused racist views. Christian Cooper is a Black birder and a longtime board member of the newly minted New York City Bird Alliance. In 2020, he made headlines after a white woman in Central Park called 911 and falsely claimed Cooper was threatening her life. Cooper also shares stories of his life and career, including his longtime LGBTQ activism and how his father’s work as a science educator inspired his lifetime passion for birdwatching.

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

In a special broadcast, we feature part of our recent in-depth interview about The Night Won’t End, a new documentary from Al Jazeera English which takes an in-depth look at attacks on civilians by the Israeli military in Gaza and the United States’ role in the war. The film follows three Palestinian families as they recount the horrific experiences they have endured under relentless Israeli assault, including the family of 6-year-old Hind Rajab, the young Palestinian girl who made headlines when it emerged in January that she had been trapped in a car with family members killed by Israeli ground troops, and the Salem family, who first lost dozens of family members in an Israeli airstrike and then additional family members who were executed by Israeli soldiers. We play clips from the documentary and speak to journalists Kavitha Chekuru and Sharif Abdel Kouddous, the director and correspondent on The Night Won’t End, respectively. We also discuss the plight of journalists in Gaza and U.S. complicity in Israel’s war. “There’s no question that U.S. weapons have killed civilians in Gaza,” says Kouddous. “This violates both international humanitarian law and domestic law.”

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Revenge of the Swine by Sue Coe.

All illustrations by Sue Coe.

“Auschwitz begins whenever someone looks at a slaughterhouse and thinks: they’re only animals.”

– Theodor Adorno

I grew up south of Indianapolis on the glacier-smoothed plains of central Indiana. My grandparents owned a small farm, whittled down over the years to about 40 acres of bottomland, in some of the most productive agricultural land in America. Like many of their neighbors they mostly grew field corn (and later soybeans), raised a few cows and bred a few horses.

Even then farming for them was a hobby, an avocation, a link to a way of life that was slipping away. My grandfather, who was born on that farm in 1906, graduated from Purdue University and became a master electrician, who helped design RCA’s first color TV. My grandmother, the only child of an unwed mother, came to the US at the age of 13 from the industrial city of Sheffield, England. When she married my grandfather she’d never seen a cow, a few days after the honeymoon she was milking one. She ran the local drugstore for nearly 50 years. In their so-called spare time, they farmed.

My parent’s house was in a sterile and treeless subdivision about five miles away, but I largely grew up on that farm: feeding the cattle and horses, baling hay, bushhogging pastures, weeding the garden, gleaning corn from the harvested field, fishing for catfish in the creek that divided the fields and pastures from the small copse of woods, learning to identify the songs of birds, a lifelong obsession.

Even so, the farm, which had been in my mother’s family since 1845, was in an unalterable state of decay by the time I arrived on the scene in 1959. The great red barn, with it’s multiple levels, vast hayloft and secret rooms, was in disrepair, the grain silos were empty and rusting ruins, the great beech trees that stalked the pasture hollowed out and died off, one by one, winter by winter.

In the late-1960s, after a doomed battle, the local power company condemned a swath of land right through the heart of the cornfield for a high-voltage transmission corridor. A fifth of the field was lost to the giant towers and the songs of redwing blackbirds and meadowlarks were drowned out by the bristling electric hum of the powerlines.

After that the neighbors began selling out. The local diary went first, replaced by a retirement complex, an indoor tennis center and a sprawling Baptist temple and school. Then came a gas station, a golf course and a McDonalds. Then two large subdivisions of upscale houses and a manmade lake, where the water was dyed Sunday cartoon blue.

When my grandfather died from pancreatic cancer (most likely inflicted by the pesticides that had been forced upon him by the ag companies) in the early 1970s, he and a hog farmer by the name of Boatenwright were the last holdouts in that patch of blacksoiled land along Buck Creek.

Sewage lagoons by Sue Coe.

Boatenwright’s place was about a mile down the road. You couldn’t miss it. He was a hog farmer and the noxious smell permeated the valley. On hot, humid days, the sweat stench of the hogs was nauseating, even at a distance. In August, I’d work in the fields with a bandana wrapped around my face to ease the stench.

How strange that I’ve come to miss that wretched smell.

That hog farm along Buck Creek was typical for its time. It was a small operation with about 25 pigs. Old man Boatenwright also ran some cows and made money fixing tractors, bush hogs and combines.

Not any more. There are more hogs than ever in Indiana, but fewer hog farmers and farms. The number of hog farms has dropped from 64,500 in 1980 to 10,500 in 2000, though the number of hogs has increased by about 5 million. It’s an unsettling trend on many counts.

Hog production is a factory operation these days, largely controlled by two major conglomerations: Tyson Foods and Smithfield Farms. Hogs are raised in stifling feedlots of concrete, corrugated iron and wire, housing 15,000 to 20,000 animals in a single building. They are the concentration camps of American agriculture, the filthy abattoirs of our hidden system of meat production.

Pig factories are the foulest outposts in American agriculture. A single hog excretes nearly 3 gallons of waste per day, or 2.5 times the average human’s daily total. A 6,000-sow hog factory will generate approximately 50 tons of raw manure a day. An operation the size of Premium Standard Farms in northern Missouri, with more than 2 million pigs and sows in 1995, will generate five times as much sewage as the entire city of Indianapolis. But hog farms aren’t required to treat the waste. Generally, the stream of fecal waste is simply sluiced into giant holding lagoons, where it can spill into creeks or leach into ground water. Increasingly, hog operations are disposing of their manure by spraying it on fields as fertilizer, with vile consequences for the environment and the general ambience of the neighborhood.

Over the past quarter century, Indiana hog farms were responsible for 201 animal waste spills, wiping out more than 750,000 fish. These hog-growing factories contribute more excrement spills than any other industry.

It’s not just creeks and rivers that are getting flooded with pig shit. A recent study by the EPA found that more than 13 percent of the domestic drinking-water wells in the Midwest contain unsafe levels of nitrates, attributable to manure from hog feedlots. Another study found that groundwater beneath fields which have been sprayed with hog manure contained five times as much nitrates as is considered safe for humans. Such nitrate-leaden water has been linked to spontaneous abortions and “blue baby” syndrome.

Pig and wirecutters by Sue Coe.

A typical hog operation these days is Pohlmann Farms in Montgomery County, Indiana. This giant facility once confined 35,000 hogs. The owner, Klaus Pohlmann, is a German, whose father, Anton, ran the biggest egg factory in Europe, until numerous convictions for animal cruelty and environmental violations led to him being banned from ever again operating an animal enterprise in Germany.

Like father, like son. Pohlmann the pig factory owner has racked up an impressive rapsheet in Indiana. Back in 2002, Pohlmann was cited for dumping 50,000 gallons of hog excrement into the creek, killing more than 3,000 fish. He was fined $230,000 for the fish kill. But that was far from the first incident. From 1979 to 2003, Pohlmann has been cited nine times for hog manure spills into Little Sugar Creek. The state Department of Natural Resources estimates that his operation alone has killed more than 70,000 fish.

Pohlmann was arrested for drunk driving a couple of years ago, while he was careening his way to meet with state officials who were investigating yet another spill. It was his sixth arrest for drunk driving. Faced with mounting fines and possible jail time, Pohlmann offered his farm for sale. It was bought by National Pork Producers, Inc., an Iowa-based conglomerate with its own history of environmental crimes. And the beat goes on.

My grandfather’s farm is now a shopping mall. The black soil, milled to such fine fertility by the Wisconsin glaciation, now buried under a black sea of asphalt. The old Boatenwright pig farm is now a quick lube, specializing in servicing SUVs.

America is being ground apart from the inside, by heartless bankers, insatiable conglomerates, and a politics of public theatrics and private complicity. We are a hollow nation, a poisonous shell of our former selves.

An earlier version of this piece originally appeared in CP +.

The post Animal Factories: On the Killing Floor appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

This content originally appeared on CounterPunch.org and was authored by Jeffrey St. Clair.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on The Real News Network and was authored by The Real News Network.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Comprehensive coverage of the day’s news with a focus on war and peace; social, environmental and economic justice.

The post The Pacifica Evening News, Weekdays – July 4, 2024 appeared first on KPFA.

This content originally appeared on KPFA – The Pacifica Evening News, Weekdays and was authored by KPFA.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Blogothèque and was authored by Blogothèque.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on openDemocracy RSS and was authored by Martin Williams.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

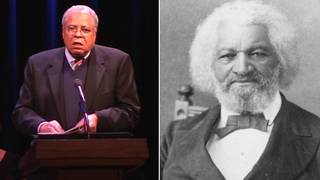

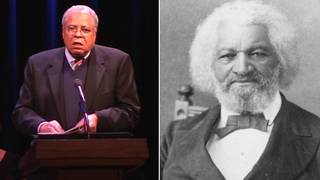

We begin our July Fourth special broadcast with the words of Frederick Douglass. Born into slavery around 1818, Douglass became a key leader of the abolitionist movement. On July 5, 1852, in Rochester, New York, Douglass gave one of his most famous speeches, “What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?” He was addressing the Rochester Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Society. James Earl Jones reads the historic address during a performance of Voices of a People’s History of the United States, which was co-edited by Howard Zinn. The late great historian introduces the address.

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

We begin our July Fourth special broadcast with the words of Frederick Douglass. Born into slavery around 1818, Douglass became a key leader of the abolitionist movement. On July 5, 1852, in Rochester, New York, Douglass gave one of his most famous speeches, “What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?” He was addressing the Rochester Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Society. James Earl Jones reads the historic address during a performance of Voices of a People’s History of the United States, which was co-edited by Howard Zinn. The late great historian introduces the address.

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

The complex web of territorial claims in the South China Sea has long been a source of tension between China and several of its Southeast Asian neighbors.

The area is strategically significant due to its rich natural resources, vital shipping lanes, and geopolitical implications. Efforts to resolve the disputes through international law, including the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, have had limited success, and the region remains a flashpoint.

Recently, CGTN, the English-language news channel of China’s state-run China Central Television, or CCTV, broadcast a documentary addressing several facets of this complex issue, including the dispute between China and the Philippines.

This program, titled “Sovereignty at Stake: A documentary on the South China Sea”, aims to present China’s historical claim to the region, but it has drawn criticism for potentially misrepresenting key aspects of the dispute.

Below is what AFCL found.

1. Was the South China Sea primarily navigated by China?

The documentary cited Wu Shicun, president of China’s National Institute for South China Sea Studies, as saying that excavated material from the sea are clear evidence that in antiquity “for a long time, it was primarily Chinese people who worked in, passed through and used the waters.”

But this is misleading.

“Common sense would tell you that the Chinese weren’t the only ones living off the ocean,” says Li Woteng, a well-known ethnic Chinese expert on the South China Sea dispute who has written several books on the subject.

Li believes that people from what is now modern China were not the only ones who navigated through and fished in the South China Sea, nor even the main ones.

As evidence, he cited a passage from a work by the 18th century Vietnamese scholar Lê Quý Đôn recording Vietnamese fishermen at work near the Paracel Islands – a disputed archipelago in the South China Sea.

Li noted that the passage also recorded a meeting between Vietnamese and Chinese fishermen working together peaceably at the site.

He added the text demonstrates that Chinese fishermen were not the only ones working in the waterway and it was used by mariners from China and many other Asian countries in antiquity.

International waterway

While the passage alone is not enough evidence to infer who entered the South China Sea first, Li believes that it was not China.

It is possible to claim that Chinese fishermen operating along the coastline of China’s southernmost Hainan Island in antiquity were “navigating” or “exploiting” the South China Sea, said Li.

However, Hainan is in the upper, northern tract of the sea, and it would be just as reasonable to infer that all surrounding countries in the region could make similar claims, Li added.

Arabs, Southeast Asians traders

Li also highlighted that when discussing sea routes in the South China Sea, known as the Maritime Silk Road, it is important to focus on the voyages made across the open ocean.

One Chinese expedition crossed the isthmus of modern day south Thailand en route to a kingdom in present day India, Li explained, citing a passage from a nearly 2,000-year-old text written during China’s Han Dynasty, which is the oldest surviving record of a Chinese expedition sent through the South China Sea.

The Indian kingdom had previously sent tribute across the South China Sea to the Han rulers, and the Chinese expedition was meant to be a reciprocal diplomatic gesture of respect.

Li added that the Indian kingdom’s initial crossing of the sea is clear evidence that the Maritime Silk Road had already become a major route for East and South Asian societies.

Additionally, these records show that Chinese envoys traveled abroad on foreign ships.

In the following centuries, records note that vessels from Southeast Asia, India and Iran regularly arrived at southern Chinese ports after crossing the South China Sea.

On the other hand, there are only a few accounts before the Tang dynasty (618-907) of Chinese people traveling by sea, and most of these were monks on foreign ships.

Li mentioned that it was only around the Song dynasty (960-1279) that China began producing large numbers of merchant vessels capable of crossing the open ocean.

By this time, Arab and Southeast Asian merchants were already using the South China Sea extensively, creating the well-known maritime trade routes that later famous Chinese explorers, like Zheng He, would follow.

2. Did international treaties stipulate that several disputed archipelagos lie outside the territory of the Philippines?

Regarding the present-day dispute between China and the Philippines over the Second Thomas Shoal and Scarborough Shoal, Wu Shicun from the National Institute for South China Sea Studies, said in the documentary that the maritime western boundaries of the Philippines are delineated at 118 degrees east by a series of international treaties.

Wu told AFCL that the 1898 Treaty of Paris, the 1900 Treaty of Washington and a border delineation signed between the United States and Great Britain in 1930 were among the international treaties he was referring to during the program.

He added that both disputed shoals lie west of this boundary and therefore do not belong to the Philippines.

This is partly true.

The 1898 Treaty of Paris was signed between the U.S. and Spain following the end of the Spanish-American War in 1898.

The treaty ceded the entirety of the then Spanish controlled Philippines to the U.S. and delineated the eastern range of islands to be handed over as lying between a longitude of 118 degrees east to 127 degrees east.

The later treaty between the U.S. and Britain delineating maritime borders between the then U.S.-controlled Philippines and British- controlled Borneo also marked an approximate longitude of 118 degrees east as the westernmost boundary of the Philippines.

However, Li Woteng noted that a clause in the 1900 Treaty of Washington – a followup agreement between the U.S. and Spain which addressed certain unresolved issues in the Treaty of Paris – further stipulated that Spain relinquished all claims to “any and all islands lying outside the lines” noted in the 1898 Treaty of Paris.

Li referred to this as a “pocket” treaty that was meant to ensure that any and all islands belonging to the Philippines during the Spanish colonial era would be handed over to the U.S., regardless of whether they were within the boundaries stipulated by the 1898 Treaty of Paris.

This clause was not mentioned by Wu. If the shoals were considered part of the Philippines during the Spanish colonial era, they may have been transferred to U.S. control along with the Philippines.

3. Does China possess more convincing historical evidence than the Philippines?

The documentary criticized the Philippines for using a 200-year-old “unofficial map” from the Spanish colonial era as evidence of its sovereignty over Scarborough Shoal since ancient times. It instead pointed to a 300-year-old Chinese fishermen’s navigation manual as more convincing evidence.

However, this lacks historical context.

While it claims the Chinese fishermen’s navigation manual is “strong evidence” that the disputed islands have been Chinese territory since ancient times, the manual was never officially commissioned by any Chinese government.

In contrast, the so-called unofficial map of the Philippines was created by the Spanish polymath missionary Murillo Velarde at the request of the then governor-general of the Philippines, Valdez Tamon, following an order from the King of Spain in 1733 to draw the first complete scientific map of the Spanish territory.

The map remained the standard chart of the Philippines for a long time after its completion. A digitized version of the map is available on the U.S. Library of Congress website.

Li, an ethnic Chinese expert on the South China Sea, stated that even if China doesn’t recognize the map drawn by Velarde as evidence of Philippine rule over Scarborough Shoal, it at least proves that the Philippines was aware of the shoal at that time.

Expeditions organized by Spain to investigate and survey the island in 1792 and 1800 could also be regarded as evidence of “effective dominion” under international law, Li added.

4. Were China’s claims to the South China Sea unchallenged by the international community?

The documentary noted that an administrative map released by the Republic of China in 1948 that includes several currently disputed islands in the South China Sea within China’s maritime borders went unchallenged by other countries at the time.

The Republic of China, or simply China, was a sovereign state based on mainland China from 1912 to 1949 prior to the government’s relocation to Taiwan, where it continues to be based today.

But this is partly true. While no country directly challenged the map at the time, several countries had already made claims to many of the islands included in the map.

In a 1996 paper by American scholar Daniel Dzurek, focusing on the issue of sovereignty over the Spratly Islands, it was noted that both Japan and France had sent several missions around the islands. France, in particular, claimed sovereignty over several islands in the region – claims that were later disputed by China.

Li believes that the most likely reason no country challenged China’s claims at the time was that nobody knew about them.

While the maps were all published in Chinese-language newspapers, they were not published prominently.

Even if other countries noticed the announcement at the time, they were probably unclear about its significance, Li explained.

“[The Republic of China] did not declare what the eleven-dash line means, and China to this day has not explicitly stated the exact meaning of the nine-dash line,” said Li.

The nine-dash line, referred to as the eleven-dash line by Taiwan, is a set of delineations on various maps that accompanied the claims of China and Taiwan in the South China Sea.

While countries such as Vietnam and the Philippines did not officially dispute China’s claimed sovereign area in the South China Sea as outlined in the map, they have declared sovereignty over particular islands and archipelagos in the region.

For instance, in 1950 the Philippines began to assert its claim to sovereignty over the Spratly Islands, and in 1956, it explicitly claimed sovereignty over them. Additionally, at the 1951 San Francisco Conference, post-independence Vietnam (represented by the Bao Dai regime) also put forward its claim of sovereignty over the Xisha and Spratly Islands.

Therefore, Li believes it is clear that the documentary’s emphasis on the fact that “no countries have objections to the eleven-dash line” is not sufficient evidence to prove there were no disputes over the islands and sea areas.

5. Did the U.S. smear China and attempt to build a military base on the Spratly Islands?

Herman Tiu-Laurel, president of the Asian Century Philippines Strategic Studies Institute, said in the documentary that the purpose of the U.S. Myoushuu Project – a Stanford University research project – was to discredit China’s international reputation and establish a joint military base of operations in the Spratly Islands, as part of a first line of island chain bases surrounding China.

But this claim lacks evidence.

While the U.S. and the Philippines announced U.S. military access to four training sites in the Philippines as part of an expansion in bilateral military cooperation in 2023, the Spratly Islands are not included among these sites.

Project Myoushuu is designed to research Chinese tactics used in the South China Sea and document Chinese encroachment in the area.

It is part of the broader Gordian Knot Center at Stanford University, a research center specializing in national security innovation established under the auspices of the U.S. Office of Naval Research.

AFCL has previously debunked similar claims about U.S. plans to build military bases in the South China Sea.

6. Did international treaties following World War II delegate which country held sovereignty over the South China Sea?

The documentary also claimed that following World War II, the Allies’ decision not to contest China’s control over various islands in the South China Sea was at least a tacit admission of China’s territorial claims over the area.

This claim is highly contestable, with the key point of contention being the wording of the Treaty of Peace with Japan, also known as the Treaty of San Francisco, signed in 1951.

Neither the government of the Republic of China nor the People’s Republic of China were signatories to the treaty.

In the second article of the treaty, Japan renounced any claims to its former imperial territories held before the war, including the Spratly Islands and the Paracel Islands.

However, the treaty itself did not specify or affirm which countries would exercise sovereignty over these territories.

Translated by Shen Ke. Edited by Shen Ke and Taejun Kang.

Asia Fact Check Lab (AFCL) was established to counter disinformation in today’s complex media environment. We publish fact-checks, media-watches and in-depth reports that aim to sharpen and deepen our readers’ understanding of current affairs and public issues. If you like our content, you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and X.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by By Rita Cheng for Asia Fact Check Lab.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

In your own words, what’s the story behind This Long Century?

The site was originally founded by myself, Stefan Pietsch, Georgina Lim, and Kate Sennert. Kate came up with the name. The idea was the same as it is now: to have a platform where people could contribute a reflection of personal meaning—how that is expressed is up to the contributor. We knew the website would take the form of a list. With the site being ever-evolving, it made sense for it to take the form of a list.

At first we simply called the project a website or a blog. But the longer it goes on, and I see the different ways that people have used it, I see how it’s grown into an archive or directory. Even more importantly than that, I think it’s an unmediated space for personal reflection.

When we started in 2008, there were some forms of social media, but a lot of outlets for artists, writers, and creators were mediated, like interviews or press releases. I found amongst my friends that there was frustration about just not having something that was unmediated. This was before Instagram and just at the start of Twitter, so [This Long Century] was a place for people to put everyday thoughts down because there wasn’t already a space for that.

How do you find new artists to talk to? I wonder if working on this for 15 years has shaped your taste.

When we started [This Long Century], it was often hard to get in contact with potential contributors. Again, this was before we were all on social media because there were folks guarding access to these people. At the time, it felt like having something that existed only online wasn’t valuable. If I’m writing to a gallery, they’re not thinking, “Oh, this would be a great place for this person to talk about whatever’s on their mind.”

By nature of those boundaries, we decided to update the site in groups of five. We always over-invite contributors and then figure it out. For example, we invite 10 people, and some say they can’t do it right now, some say they’re not interested, or can’t commit to the deadline.

Within the commercial world, so many people have deadlines that exist that are inflexible. We never want to apply pressure to people. If you can’t make the deadline, then we’ll figure it out. What I’m getting at is that so much of the project—the archive—is out of my control.

You set out thinking these five contributors will work well together. And if one or two drop out, what you end up with in terms of an update is not what you started with. That’s the beauty of it because it’s not like our updates have been timed around certain launches or screenings–

It’s not tied to the urgency of a press cycle, yeah.

By the nature of it, it’s organic. It takes whatever form. We were very fortunate early on to have the support of artists like Collier Schorr, Mary Ellen Mark, Les Blank.

The other thing we did was look at people who contribute and ask, “Who have they worked with?” The site has this constellation built into it. I’m sure you could draw threads between people that have worked together, or who are friends. Something I have to say about everyone who has contributed to the site is that they are opening themselves up and allowing us to see things that we otherwise wouldn’t be able to experience.

Could you elaborate on what you mean by ‘unmediated’?

I think about publications like Index Magazine, which was always great because a lot of the conversations would have the ‘ums’ and the ‘ahs’ and everything in there. I never thought of what we did with This Long Century as curation. That’s not imposter syndrome, I just don’t see it as that. I just see it as it’s an archive that we’re building.

I try not to center myself in the project. I rarely edit anything for the site. Unless someone says, “I want you to edit this,” I don’t touch it. Sure, maybe sometimes spelling mistakes, but I think there’s something beautiful about contributions that have texture and cadence and that you can feel the person in that moment, in that piece. If someone’s rushing and flustered or whatever, I like to lay it all out for people to see. It’s this idea of the role of an editor as a ‘beginner’ or a ‘non-expert,’ and not an authority figure. I don’t want to be the editor who comes in and says, “Okay, move this around, change this, do that.” I don’t want to dictate what people do. It should be open to contributors to give as little as much as they want to give. Sometimes, people contribute one photograph or one sentence, and that contribution can be as meaningful as one that’s 500 words. This Long Century is a place for all of it.

We’re also always finding ways to engage with past contributors. One thing we decided early on was that for every 100 posts, we would hand over the curatorial duties to past contributors and invite them to nominate people. Again, it’s a way to almost randomize the list, to loosen any kind of control or hierarchy or sense of the hand of a single person. I never want it to feel like there’s just one person making decisions over the contributions.

You’re creating a space for people to present something on their terms as opposed to being written about by someone in the third person. I’m saying this as someone who’s writing a piece about your project!

These days particularly, artists get asked to do so much by their galleries, among others. They’re expected to have a presence online. Often, they’re told to behave a certain way. Filmmakers put out films and studios tell them they have to repost and promote. I think it’s terrible because one should be able to create a piece of artwork, put it out in the world, and not have to explain it.

How hard can you push something from being unmediated? I’d love to get to a point where I actually don’t do anything for This Long Century. I’m not talking about AI, but maybe the next cycle is that I remove myself from the site, and finally just give myself over to serve the contributors and facilitate.

Did you know when you started that the project would go on for this long?

No! [laughs] When we started, the intention was kind of selfish. When I moved to New York, I was trying to find a way to engage with people beyond the surface level, like what usually happens at art openings. The site was a way for me to engage deeply and to learn a bit more about others, through personal experiences I hadn’t seen presented elsewhere. We don’t have a 5-year, 10-year, 15-year plan for This Long Century. In fact, that there’s been so little written about the project tells you that we don’t really know what we’re doing.

This Long Century speaks for itself.

There’s no PR machine; no interns or assistants. People will find it if they want to find it. I’ve always thought it’s okay for the site to be a slow burn. It doesn’t have to be ‘of the moment’ or up-to-date. I think it should just be online for people to dig into whenever they feel like they want to, whether it’s once a month, once a year, or every couple of years.

The design and layout of the site have never changed either. People have suggested different things, like adding keyword searches. But I’ve always felt like that if you need to take the time to go through it, then that’s probably a good thing. As our life online progresses, our sense of discovery has been taken away from us. Everything’s simplified so we can move faster. And so if you log onto the site and your engagement first starts with, “Oh, I know this name,” and you dig through those, you think “Oh, who’s the person next to this person?” Then it leads you down one hole. That’s probably a good thing.

I return to the site whenever I feel lost, and my experience is unique to the place and time I come from. I’ll revisit certain posts and new meanings will erupt, or I’ll find a new artist to fall in love with. I’m curious if any contributions come to mind for you that epitomize This Long Century.

Having never really changed what we’re asking of people, I find it interesting that there are certain threads throughout. There are of course some surprises, but there are throughlines—odes to friends and family, or expressing grief. Another thread talks about the artistic process. I think this is a really special thing because I can’t think of many other outlets in which people get to be transparent about not just the work process, but how their work is made in community.

I’m now thinking of the contribution by Ayo Akingbade. That’s one of my favorite ones, where she’s making a portrait together with her friend.

Ayo had been collecting Nigerian records for years, and a lot of those that Ayo put up on her site, I have the original record. So we got into this deep conversation, and we’re friends now. I was fortunate to play a small role with helping produce her latest film, KEEP LOOKING. We’ve produced films for other past This Long Century contributors: Sara Cwynar, Sam Contis, and just recently, Mark MckNight, in partnership with producer Myriam Schroeter (who co-founded our sister project, Ecstatic Static). That’s the other side of it—I’ve had a lot of friendships that have developed out of these exchanges because someone’s sharing something so personal with you that often the only way to respond as an editor is to reciprocate with something personal. The site would not exist without the generosity of the contributors. So I’m very grateful for that. I know how fortunate we are.

How would you describe the community that has formed around This Long Century?

People gravitate towards it. I still think that’s a pretty special thing. It is truly supposed to be for the artists, photographers, writers, poets, musicians, and filmmakers themselves.

At one point just before the pandemic, I wanted to create a reading room with my books, and also books by past contributors. A space where people can come and gather and read and exchange ideas. We didn’t sign a lease on that space because three weeks later, everything shut down because of COVID-19. I think at one point in time, there could be a physical version of This Long Century place to gather, exchange ideas, and have a safe place to exist.

But there are instances where The Long Century trickles into the real world.

When I work on anything that we do that exists away from the online archive, I’m very weary of undermining the [initial manifestation of the] project. It has to be a different version. If we made a book, we couldn’t just simply take [the site], put it into a book, and be done. That would be too definitive; not open-ended enough. The site has to, in all its forms, exist in an open-ended way. That’s the only reason it’s online. We could have started This Long Century as a journal or a book, but then we would risk creating a hierarchy. That’s why the site takes the form of a list.

We’re always finding ways to engage with people again since they can’t make a second contribution to the site. In 2015, we did a month-long program at Spectacle Theater. We did the recent Criterion Channel program, which was centered around the idea of artists making other work in communication with other artists. We’re starting a “This Long Century Presents…” screening series at Metrograph—each one will be centered on one contributor’s work.

The next volume of Speciwomen will be a curation of This Long Century’s archive, a box set made up from a selection of past contributions, this will be out first printed form of This Long Century. I’m not involved past helping connect Philo Cohen, the editor, with past contributors, I love that it’s her curation of our archive.

We had the exhibition last year at Dunes Gallery in Maine. That was the first time we’d ever done anything resembling a physical manifestation of the site. This was around This Long Century’s 15th anniversary. I’d been thinking a lot about our beginnings, where we started from. I’ve been taking a lot of time to go through past contributions. With that fresh in my mind, it made sense to go to artists and say, “How did you begin? What was your starting point?”

Our site has always been less of a definitive statement and more of a jumping-off point. So whatever we were going to do [to supplement the site] should also feel like that. To show something from the first couple years of an artist making work creates intrigue. You know, like, “Well, this is not what they’re known for… how did they get from there to here?”

It was fun digging through people’s old work. A lot of the time, artists would say, “I don’t even know what that work is,” or “That’s in storage, come get it.” Again, I think about the idea of time; how as a creator… your work, your process, your ideas, change constantly.

I love the idea of showing where people come from—beginnings—because it’s before anything makes sense. You don’t know what you’re doing. We’re all making mistakes—there’s a lot of energy here, and we’re just working with that. I think it’s great to make mistakes. And I was fortunate that people were open to showing work that maybe doesn’t represent where they’re at now. There’s a sense of vulnerability both to that exhibition and the archive as a whole.

You have a background in filmmaking and creative direction. I’m curious about what the experience of running this site has taught you about your practice.

The site is really about creating a space that is open-ended, non-hierarchical, and unmediated. If I think about what This Long Century stands for, and about my creative, personal, and political interests, they align in that both lead to this understanding that nothing is done in isolation. You have to work collaboratively with people—you need to decenter yourself; to be open to other ways of doing things… to other ideas, other people. These are things that I’ve always felt believed and understood in theory, but I think the site shows how to put that into practice.

Jason Evans recommends:

Pare de Sufrir by AG Rojas. We were fortunate for the chance to screen AG’s latest film in March, as part of our ongoing series at Metrograph (NY) and Now Instant Image Hall (LA). In keeping with the artist’s generous approach to his work, AG has now made the film available for people to watch worldwide for free. It’s a real gift, that prioritizes healing in this moment of unbearable grief.

The Great Book Return is an archive/reading room of books and shared resources related to Palestinian liberation, based in my hometown of Naarm/Melbourne. Established by local curators/writers Anna Emina and Celine Saoud, the archive was given its name in response to the 70,000 Palestinian books that were looted from public libraries and private collections during the 1948 Nakba.

People’s Library for Liberated Learning, as part of the students ‘Gaza Solidarity Encampments’ across university campuses in the US (and now worldwide), many started their own free libraries, providing access to books, hosting poetry readings, small teach-ins, etc. Initiated by the Columbia Students for Justice in Palestine, this action feels especially significant in NYC where our corrupt mayor has cut city funding for libraries, forcing them to close on Sundays, while increasing NYPD spending by billions.

Close to the Knives by David Wojnarowicz. I have a t-shirt that reads ‘Books are Weapons’, which may be the best way to describe this collection of personal essays first published in 1991, by the great artist and activist David Wojnarowicz, who died of AIDS at age 37.

Gaza Mutual Aid Solidarity was started by a group of friends with loved ones in Gaza. Through micro-fundraisers this initiative has been raising money for the distribution of food and supplies on the ground in Gaza, including building solar panels to enable refrigeration and clay ovens for cooking. They continue to evolve as the genocide rages on, offering many ways to support their efforts… as we did with our own Gaza Kite Auction, together with artists Anna Sew Hoy, Ava Woo Kaufman, Narumi Nekpenekpen, Stanya Kahn, Wilder Alison, Willa Nasatir, and Yto Barrada.

This content originally appeared on The Creative Independent and was authored by Alex Westfall.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Laura Flanders & Friends and was authored by Laura Flanders & Friends.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on The Real News Network and was authored by The Real News Network.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on The Real News Network and was authored by The Real News Network.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

“There’s our carbon footprint to think about, and then there’s also our cultural footprint — both of which are important, but this industry is uniquely positioned to have a large cultural footprint.”

— Sam Read, executive director of the Sustainable Entertainment Alliance

Dearest gentle reader,

One thing about me is that I love a good (or medium-good, or downright trashy) TV show. Last summer, we covered the rise of climate mentions and plotlines in mainstream movies and shows — something I had begun to witness as a casual viewer.

But recently, I’ve also been thinking about the fact that the shows I binge so voraciously come with their own carbon footprint, much like any other product that we consume. Producing a piece of media requires energy, transportation, filming and audio equipment, food, wardrobes, props, and a host of other resources.

Just as film creators and studios are increasingly considering how to weave climate narratives into their projects, the industry is also grappling with the challenge of decarbonizing behind the scenes.

“The biggest source of emissions for our industry, at least in terms of production, is fuel,” said Sam Read, executive director of the Sustainable Entertainment Alliance. That includes not only vehicles that bring equipment, catering, and people to set, but also a source you might not immediately think of: diesel generators. TV and film productions often shoot on location, including in remote areas, and rely on a setup of trailers. Diesel-powered generators have long been the industry standard for supplying power to these sets. And diesel is a particularly dirty fuel, causing air pollution with a range of known health effects.

The Sustainable Entertainment Alliance (formerly the Sustainable Production Alliance), a coalition of leading studios and streamers working toward sustainability in the industry, offers tools like a carbon calculator for productions and a checklist for implementing sustainable practices — such as donating uneaten craft services food, using responsibly sourced plywood to build sets, or buying used items for set decoration.

And a big one is swapping out those old diesel generators for a variety of cleaner alternatives, including hydrogen and solar power, which a few recent productions have started to make use of.

In many cases, the switch to greener practices isn’t just about helping the climate. These modern technologies are also healthier and more efficient. “There are so many benefits to the alternatives to diesel generators — one of them obviously being emissions — but they’re also quieter and less polluting,” Read said. For that reason, they can be situated closer to “video village” (where the director sits on a film set, observing the action from various monitors), eliminating some of the need for long cables.

The alliance, which already includes major players like Disney, Amazon Studios, Netflix, and Paramount Pictures, is working to broaden its membership. Read sees a growing appetite for decarbonization in the entertainment industry, driven in part by advocacy from unions like The Producers Guild of America, which helped create the sustainable production checklist. (Check out the 2022 Hollywood Reporter report on sustainability for more stories of how studios have embedded climate goals into productions.)

The alliance and other groups are also advocating for more climate stories onscreen. But in another part of the industry, the distinction between what happens behind the scenes and on camera is a little fuzzier, creating unique opportunities to both decarbonize and model sustainability to viewers. That’s reality TV — my truest and guiltiest pleasure.

“It is such a good year for sustainability on TV,” said Cyle Zezo, an executive producer and the founder of Reality of Change, an initiative focused on sustainability and climate storytelling opportunities in unscripted entertainment, including documentaries, reality TV, and game and competition shows.

On average, Zezo said, the footprint of an unscripted show is likely to be smaller than a scripted production. Producers of these shows may contend with some of the same issues — like the need for clean energy to power equipment in remote filming locations. But generally, the clean production practices on a reality show or documentary are simply reflecting the way real people live their lives.

When we spoke for my story last year, for instance, Zezo highlighted compost bins on the set of a cooking show called Recipe for Disaster, and how the crew intentionally showed them during filming. Also last year, Netflix announced a partnership with General Motors to use more electric vehicles in shows like Love Is Blind and Queer Eye.

“I’m gonna make a prediction, and I hope I’m right, that climate and sustainability representations are only going to continue to grow in this area over the coming years,” Zezo said.

I asked Zezo, Read, and others to point me toward some recent shows and movies that have embedded sustainability into their productions in new or interesting ways. These series and movies may not all appear to be climate-related, but they can all help decarbonize your summer watch list.

![]()

Bridgerton. That’s right, dear readers. This steamy romance series set in the Regency era in London took a more modern approach to sustainability in the production of its third season. In a set tour, two actors from the show describe how the cast trailers and work trucks were all powered by a hydrogen power unit supplied by British company GeoPura. The production also omitted beef from craft services due to its outsized carbon footprint.

The Decameron. This upcoming show (premiering July 25), loosely inspired by the short story collection of the same name, tells the story of a debaucherous retreat in the Italian countryside as wealthy nobles, and their servants, attempt to avoid the bubonic plague. This show also pursued clean energy in its production; its base camp ran on batteries charged by solar panels, according to Netflix.

Bosch: Legacy. A third show replacing diesel generators on set, this is the next chapter of a seven-season police procedural drama following the career of detective Harry Bosch. The show was among the first to use mobile battery units designed by a company called Moxion.

Sitting in Bars With Cake. This 2023 movie, starring Yara Shahidi, Odessa A’zion, and Bette Midler, is about friendship, navigating life in your 20s, and, as the title would suggest, cake. It also used Moxion’s mobile clean-tech batteries on set.

The Gilded Age. In the second season of this historical drama, producers took a more holistic approach to get the show off diesel power. “They actually installed power lines — like they put in power poles and a whole power system in the backlot area where they were shooting,” Heidi Kindberg, the vice president of sustainability at Warner Bros. Discovery, told The Hollywood Reporter. That enabled the show to go generator-free when shooting its second season in New York.

True Detective: Night Country. The fourth season of this critically acclaimed crime drama takes place in the Arctic — it was filmed in Iceland, where the production was able to draw on the country’s nearly 100-percent renewable energy grid. Where remote power was needed, the show piloted an electric battery generator called the Benerator. According to a report from the Producers Guild of America, the show’s creators also slashed waste by placing recycling and compost bins and water-fill stations around set. And, this season features a climate-related storyline.

Homegrown. In this series, now in its fourth season, Atlanta-based farmer and food activist Jamila Norman helps homeowners transform their yards into urban farms, while discussing the many benefits that farms and gardens can bring to communities. Zezo loves how it invites viewers in, showing them how anyone can do the things shown onscreen.

Building Outside the Lines. This quirky build show follows father-daughter duo Jared (“Cappie”) and Alex Capp as they take on bespoke design and construction projects, largely in their South Dakota community. Zezo noted that its sustainability themes are subtle, showcasing the use of electric power tools and unconventional or upcycled materials, like shipping containers.

OMG Fashun. This competition show, co-hosted by Julia Fox and Law Roche, is all about upcycled fashion — it’s Project Runway meets Chopped. The show is incredibly on-message with its themes of sustainability and reuse, Zezo said, without coming across as stuffy or preachy. “It’s just so sharp and creative and, like, absolutely wild fun.”

Family Switch. OK, this is a holiday movie — so maybe save it for a few months (or for a night when you just need something cozy). It’s a Freaky Friday-inspired family romp starring Jennifer Garner and Ed Helms, and according to Netflix it ran on electric vehicles. Four EV passenger vans transported the crew, another brought the catering and production items, and an electric pickup truck pulled the director’s trailer. An EV makes an onscreen appearance as well — it’s brief, but the family’s Polestar 2 shows up in at least one scene.

— Claire Elise Thompson

In March, the advocacy group Gas Leaks Project launched an awareness campaign about the health dangers of gas stoves — in the form of a reality TV show trailer. The made-up show was dubbed Hot & Toxic, a spoofy take on a house-full-of-hot-and-melodromatic-young-singles style of show, where the house is that of a new and unsuspecting homeowner, and the singles are personified forms of the cancer-causing chemicals spewing out of her stove.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline These TV shows are leaving emissions on the cutting room floor on Jul 3, 2024.

This content originally appeared on Grist and was authored by Claire Elise Thompson.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

“There’s our carbon footprint to think about, and then there’s also our cultural footprint — both of which are important, but this industry is uniquely positioned to have a large cultural footprint.”

— Sam Read, executive director of the Sustainable Entertainment Alliance

Dearest gentle reader,

One thing about me is that I love a good (or medium-good, or downright trashy) TV show. Last summer, we covered the rise of climate mentions and plotlines in mainstream movies and shows — something I had begun to witness as a casual viewer.

But recently, I’ve also been thinking about the fact that the shows I binge so voraciously come with their own carbon footprint, much like any other product that we consume. Producing a piece of media requires energy, transportation, filming and audio equipment, food, wardrobes, props, and a host of other resources.

Just as film creators and studios are increasingly considering how to weave climate narratives into their projects, the industry is also grappling with the challenge of decarbonizing behind the scenes.

“The biggest source of emissions for our industry, at least in terms of production, is fuel,” said Sam Read, executive director of the Sustainable Entertainment Alliance. That includes not only vehicles that bring equipment, catering, and people to set, but also a source you might not immediately think of: diesel generators. TV and film productions often shoot on location, including in remote areas, and rely on a setup of trailers. Diesel-powered generators have long been the industry standard for supplying power to these sets. And diesel is a particularly dirty fuel, causing air pollution with a range of known health effects.

The Sustainable Entertainment Alliance (formerly the Sustainable Production Alliance), a coalition of leading studios and streamers working toward sustainability in the industry, offers tools like a carbon calculator for productions and a checklist for implementing sustainable practices — such as donating uneaten craft services food, using responsibly sourced plywood to build sets, or buying used items for set decoration.

And a big one is swapping out those old diesel generators for a variety of cleaner alternatives, including hydrogen and solar power, which a few recent productions have started to make use of.

In many cases, the switch to greener practices isn’t just about helping the climate. These modern technologies are also healthier and more efficient. “There are so many benefits to the alternatives to diesel generators — one of them obviously being emissions — but they’re also quieter and less polluting,” Read said. For that reason, they can be situated closer to “video village” (where the director sits on a film set, observing the action from various monitors), eliminating some of the need for long cables.

The alliance, which already includes major players like Disney, Amazon Studios, Netflix, and Paramount Pictures, is working to broaden its membership. Read sees a growing appetite for decarbonization in the entertainment industry, driven in part by advocacy from unions like The Producers Guild of America, which helped create the sustainable production checklist. (Check out the 2022 Hollywood Reporter report on sustainability for more stories of how studios have embedded climate goals into productions.)

The alliance and other groups are also advocating for more climate stories onscreen. But in another part of the industry, the distinction between what happens behind the scenes and on camera is a little fuzzier, creating unique opportunities to both decarbonize and model sustainability to viewers. That’s reality TV — my truest and guiltiest pleasure.

“It is such a good year for sustainability on TV,” said Cyle Zezo, an executive producer and the founder of Reality of Change, an initiative focused on sustainability and climate storytelling opportunities in unscripted entertainment, including documentaries, reality TV, and game and competition shows.

On average, Zezo said, the footprint of an unscripted show is likely to be smaller than a scripted production. Producers of these shows may contend with some of the same issues — like the need for clean energy to power equipment in remote filming locations. But generally, the clean production practices on a reality show or documentary are simply reflecting the way real people live their lives.

When we spoke for my story last year, for instance, Zezo highlighted compost bins on the set of a cooking show called Recipe for Disaster, and how the crew intentionally showed them during filming. Also last year, Netflix announced a partnership with General Motors to use more electric vehicles in shows like Love Is Blind and Queer Eye.

“I’m gonna make a prediction, and I hope I’m right, that climate and sustainability representations are only going to continue to grow in this area over the coming years,” Zezo said.

I asked Zezo, Read, and others to point me toward some recent shows and movies that have embedded sustainability into their productions in new or interesting ways. These series and movies may not all appear to be climate-related, but they can all help decarbonize your summer watch list.

![]()

Bridgerton. That’s right, dear readers. This steamy romance series set in the Regency era in London took a more modern approach to sustainability in the production of its third season. In a set tour, two actors from the show describe how the cast trailers and work trucks were all powered by a hydrogen power unit supplied by British company GeoPura. The production also omitted beef from craft services due to its outsized carbon footprint.

The Decameron. This upcoming show (premiering July 25), loosely inspired by the short story collection of the same name, tells the story of a debaucherous retreat in the Italian countryside as wealthy nobles, and their servants, attempt to avoid the bubonic plague. This show also pursued clean energy in its production; its base camp ran on batteries charged by solar panels, according to Netflix.

Bosch: Legacy. A third show replacing diesel generators on set, this is the next chapter of a seven-season police procedural drama following the career of detective Harry Bosch. The show was among the first to use mobile battery units designed by a company called Moxion.

Sitting in Bars With Cake. This 2023 movie, starring Yara Shahidi, Odessa A’zion, and Bette Midler, is about friendship, navigating life in your 20s, and, as the title would suggest, cake. It also used Moxion’s mobile clean-tech batteries on set.

The Gilded Age. In the second season of this historical drama, producers took a more holistic approach to get the show off diesel power. “They actually installed power lines — like they put in power poles and a whole power system in the backlot area where they were shooting,” Heidi Kindberg, the vice president of sustainability at Warner Bros. Discovery, told The Hollywood Reporter. That enabled the show to go generator-free when shooting its second season in New York.

True Detective: Night Country. The fourth season of this critically acclaimed crime drama takes place in the Arctic — it was filmed in Iceland, where the production was able to draw on the country’s nearly 100-percent renewable energy grid. Where remote power was needed, the show piloted an electric battery generator called the Benerator. According to a report from the Producers Guild of America, the show’s creators also slashed waste by placing recycling and compost bins and water-fill stations around set. And, this season features a climate-related storyline.

Homegrown. In this series, now in its fourth season, Atlanta-based farmer and food activist Jamila Norman helps homeowners transform their yards into urban farms, while discussing the many benefits that farms and gardens can bring to communities. Zezo loves how it invites viewers in, showing them how anyone can do the things shown onscreen.

Building Outside the Lines. This quirky build show follows father-daughter duo Jared (“Cappie”) and Alex Capp as they take on bespoke design and construction projects, largely in their South Dakota community. Zezo noted that its sustainability themes are subtle, showcasing the use of electric power tools and unconventional or upcycled materials, like shipping containers.

OMG Fashun. This competition show, co-hosted by Julia Fox and Law Roche, is all about upcycled fashion — it’s Project Runway meets Chopped. The show is incredibly on-message with its themes of sustainability and reuse, Zezo said, without coming across as stuffy or preachy. “It’s just so sharp and creative and, like, absolutely wild fun.”

Family Switch. OK, this is a holiday movie — so maybe save it for a few months (or for a night when you just need something cozy). It’s a Freaky Friday-inspired family romp starring Jennifer Garner and Ed Helms, and according to Netflix it ran on electric vehicles. Four EV passenger vans transported the crew, another brought the catering and production items, and an electric pickup truck pulled the director’s trailer. An EV makes an onscreen appearance as well — it’s brief, but the family’s Polestar 2 shows up in at least one scene.

— Claire Elise Thompson

In March, the advocacy group Gas Leaks Project launched an awareness campaign about the health dangers of gas stoves — in the form of a reality TV show trailer. The made-up show was dubbed Hot & Toxic, a spoofy take on a house-full-of-hot-and-melodromatic-young-singles style of show, where the house is that of a new and unsuspecting homeowner, and the singles are personified forms of the cancer-causing chemicals spewing out of her stove.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline These TV shows are leaving emissions on the cutting room floor on Jul 3, 2024.

This content originally appeared on Grist and was authored by Claire Elise Thompson.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

As anti-imperialist sentiment gains momentum in Africa, the Alliance of Sahelian States has demonstrated a clear resolve to reclaim sovereignty from foreign powers. The backlash against Western presence, and French presence in particular, has ignited a broader conversation about the future of foreign intervention and the true path to self-determination for African nations. Yet, while AFRICOM and Western military forces are being pushed out of the Sahel by people’s movements, we see a much different relationship elsewhere on the continent taking note, in particular, of the ongoing close coordination between the US and Botswana Defense Forces as well as the US and Kenya Defense forces even as they are illegitimately deployed against their own civil society.

With Kenya as a current poster child, we observe that in Africa, there are hundreds of political parties that do not serve the interests of African people. These parties serve as middlemen between imperialism and the masses of the people. But even in more convoluted or reactionary political environments, there is always pushback. In tandem with the events in the Sahel, Kenya is witnessing its own wave of resistance against neocolonialism, particularly in the form of protests against President William Ruto and his collusion with the IMF to further immiserate the Kenyan people on behalf of Western interests. Ruto has also sent Kenyan police to Haiti, ostensibly to serve Western imperialist agendas under the guise of peacekeeping, in a plan crafted in large part by Meg Whitman, U.S. ambassador to Kenya. These moves have been met with significant opposition within Kenya, highlighting a broader continental struggle against foreign domination and exploitation. The ongoing events signal a rising Pan-African consciousness that seeks to dismantle the remnants of colonialism and resist new forms of imperialist control.

AFRICOM Watch Bulletin spoke with Salifu Mack who is a high school English and History teacher, music lover, and sparkling water connoisseur. He is also a member of the Black Alliance for Peace and the All African People’s Revolutionary Party and an organizer with the Lowcountry Action Committee in the Lowcountry of South Carolina.

AFRICOM Watch Bulletin: You recently spent time on the ground in Burkina Faso during or shortly after the uprisings that led to the backlash against the French colonialists. Did you feel that this was just another military coup in Africa or that this was different and why?

Salifu Mack: Even before arriving in Burkina Faso, it was quite clear to me that the character of this coup was different from what is commonly associated with coups in Africa. My comrades on the ground at the Thomas Sankara Center for African Liberation and Unity had been reporting for months prior about the sentiment that had been emanating from the masses.

During my time in Burkina Faso, it was quite clear to me that the movements of the Traore administration have been in direct response to, and many cases, in lock-step with the demands of the people of Burkina Faso. While many coups in Africa are a top-down imposition of the will of a few “strong-men”, moves in Burkina Faso such as the ejection of the French military, embassies, and certain NGO and media properties, were demands originally spurring from the grassroots. The military coup led by Captain Ibrahim Traore just provided the muscle to move those demands into reality.

This is quite different from the January 2022 coup that preceded Traore, led by Paul-Henri Sandaogo Damiba. That coup administration was deeply unpopular with the masses and lasted only 8 months. Often in Western circles, it is easy to discuss the African masses as people who lack discernment, but the reaction to Damiba contrasted against the positive reaction to Traore should be enough proof to demonstrate that people in Burkina Faso are using sound reasoning and discernment skills to determine what is in their best interests.

AFRICOM Watch Bulletin: Clearly, France was the primary target among foreign interests. What signs, if any, did you see that the focus would then shift to US AFRICOM next or in the future?

Salifu Mack: On February 2, 2024, I attended a rally outside of the U.S. Embassy in Burkina Faso, organized by an organization called the Black African Defence League. The group was there to deliver a letter to the US ambassador to Burkina Faso, demanding US military bases withdraw from the country immediately.

They also denounced US imperialist policy, stating that U.S. interference in the affairs of the Alliance of Sahel States would not be tolerated by the popular administrations and that consequences for such interference would be backed by the masses of the country. I remember being so blown away not just by this action, but by the very clear analysis that members of the organization displayed regarding imperialism.

They understood quite clearly the essence of the idea that imperialism is the primary contradiction in the world today, and they situated the U.S. at the center of that. They were declaring that while France has been the most visible hand in the oppression they’ve experienced, France would never have such abilities without the backing of the U.S. and NATO more explicitly. They pointed directly to the 2011 NATO-led invasion of Libya as a material starting point for the issue of terrorism plaguing the Sahel today. Two months later, the U.S. was dismissed by Niger, and the action was widely celebrated across Burkina Faso.

AFRICOM Watch Bulletin: With the exit of the French, a power vacuum has been created in the Sahel. Some suspect that the US will fill that vacuum. Others think that Russia via its Wagner group or China might fill that void. In your view, how best can Africans fill that void?

Salifu Mack: This question comes up quite commonly in western Pan-Africanist spaces and I just want to point out that it goes back to what I mentioned in my first response, but unfortunately it’s going to be a little long-winded. Africans in the Sahel are not being lulled into compliance by the scent of some fancy Russian perfume or the promise of sweet words. The Sahel is a region of Africa that has been absolutely ravaged by the results of years of Western meddling in African affairs, direct and indirect. The Sahel has also, up to the point of establishing a relationship with Russia, received close to no real material support from any outside forces to help tackle that problem.

The Sahel is surrounded by countries that at best are hollowed-out shells of nations due to years of neocolonial leadership, and at worst, are treacherous lackeys of Western imperialism who willingly engage in acts of sabotage against nations who won’t comply with it. This question and criticism are also often raised by the Western diaspora, who must be mindful of our inability to materially change anything about our situations abroad, and who should be honest about the fact that our powerlessness has led to a passive complicity with U.S. imperialism. With that context in mind, I think we must discuss Sahelian partnerships with Russia, or whoever else they may engage with in the future, with a bit of humility.

While navigating desperate conditions, leaders of the AES have still managed to initiate quite meaningful security partnerships with the Russian state. Russian flags stand tall beside flags of Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger at roundabouts in all three countries. And it is not because Burkinabe are engaged in a delusion of “friendship” but because they understand the utility of strategic alliances.

In an ideal world for most people I encountered, Africa solves its own problems. However, the Sahel is forced to deal very acutely with the reality that Africa at this very moment has been conquered. They are also more honest about the reality that Africa does not exist in a world apart from the rest of this planet. Sahelian partnerships with Russia have assisted in the longstanding fight against terrorism, creating space and opportunity for meaningful attempts at development. The need for development in the Sahel states is an ill-understood aspect of the struggle there.

The concern moving forward, in my opinion, needs to be less about filling a void, and more about building upon the achievements of the current struggle. This phase in the AES is just a building block, and each of us has a role to play in building new ones. Africans in the West need to turn our attention towards AFRICOM (through organizations like the Black Alliance for Peace) because its meddling against the region is only going to escalate from here. I also think that we need to be engaged in moving resources to organizations in the Sahel, like the Thomas Sankara Center so that they can continue to facilitate opportunities for in-person work with the masses throughout the region. There are quite energetic anti-imperialist and socialist organizations in the Sahel. Organizations are attempting to do a lot at this moment with very limited resources. The defense of our liberated territories has to be a priority because as these nations increase their capacity, they can increase the power of their material contributions toward the struggle for Pan-Africanism, which is also a very clear motivation of the masses in these countries. I have never encountered Africans with a more serious commitment to pan-African unity than I did in Burkina Faso.

AFRICOM Watch Bulletin: What evidence of structural or policy changes can you identify on the ground that has directly and positively impacted the material reality of the masses since the uprisings and coup?

Salifu Mack: The Traorè administration has received a lot of positive attention for kicking out the French military, NGOs, and enemy media, and rightfully so. I think many people living in the deluded realities of Western states that commit and fund terrorism but do not have to bear the brunt of terrorists running around unchecked, can not appreciate how meaningful it is to Burkinabè to see their anxieties about security being dealt with effectively for the first time in years. But in my opinion, more attention should be paid to the administration’s intense focus on development.

Captain Ibrahim Traoré has demonstrated that he is wholly invested in the process of nationalizing Burkina Faso’s resources. In 2023, the administration announced it would be nationalizing the sugar sector. The SN SOSUCO sugar company, which was once privatized during the term of the counterrevolutionary president, Blaise Compaoré, is now state-owned.

This administration has also positioned Burkina Faso, one of Africa’s foremost gold-producing states, to develop technology to process gold mine residues on-site. Construction on the factory began in November, and it was opened this January. In his formal announcement, Captain Ibrahim Traoré noted that the facility is 40% owned by the state.

In addition, Burkina Faso has long implemented land reform policies limiting the amount of land that can be privately possessed to 5 hectares. To boost production, the current administration is subsidizing the cost of agricultural equipment for farmers and has set a goal to increase the productivity of irrigated areas by at least 50%.

AFRICOM Watch Bulletin: Many African people in the United States question why we should care about what goes on in the Sahel. How would you respond to this and how can those who do care get involved?

Salifu Mack: In chapter 19 of Africa Must Unite, Kwame Nkrumah states that “… any effort at association between the states of Africa, however limited its immediate horizons, is to be welcomed as a step in the right direction: the eventual political unification of Africa.” In my observation, the average, everyday African in Burkina Faso is extremely concerned with the total unity of not just the Sahelian states, but all of Africa. It’s my most sincere hope that the AES can model something that will be the envy of Africans across the continent. The AES states have taken on a huge responsibility which must be delivered on by any means necessary. And this means that Africans everywhere — we are around the world — have a responsibility to defend it.

This defense, however, can not be actualized as passionate individuals reposting content on social media. We have to be members of political formations with clear principles, and goals, that have an emphasis on political education and action. We need to develop an analysis that helps to draw very succinct connections between what is going on in places like the Sahel and Haiti, and places like Baltimore and Los Angeles. Places where concepts like “terrorists” and “gangs” are being weaponized against the African masses to manufacture consent for police brutality and imperialist invasion.

There is no cure for the Democratic Republic of the Congo, no way to “free” Sudan, no end to settler colonialism in Western Sahara, or true liberation for Africans in the United States without this unity. No confrontation of violent client states, or our ruthless petit bourgeoisie. No path to true development— not a single road or hospital built truly to our advantage. There is no way forward for our individual states in this modern era that does not involve political and economic unity, and unity presupposes organization. Word to Nkrumah!

The post U.S. Out of Africa: Voices from the Struggle first appeared on Dissident Voice.

This content originally appeared on Dissident Voice and was authored by Black Alliance for Peace.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Just Stop Oil and was authored by Just Stop Oil.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by Radio Free Asia.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by Radio Free Asia.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on ProPublica and was authored by ProPublica.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on ProPublica and was authored by ProPublica.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.