This content originally appeared on The Intercept and was authored by The Intercept.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on The Intercept and was authored by The Intercept.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Blogothèque and was authored by Blogothèque.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on VICE News and was authored by VICE News.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty and was authored by Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

The U.S. military ran a secret anti-vaccination campaign at the height of the pandemic in the Philippines and other nations to sow doubt about COVID vaccines made by China, according to a new investigation by Reuters. The clandestine Pentagon campaign, which began in 2020 under Donald Trump and continued into mid-2021 after Joe Biden took office, relied on fake social media accounts on multiple platforms to target local populations in Southeast Asia and beyond. The campaign also aimed to discredit masks and test kits made in China. “Within the Pentagon, within Washington, there was this fear that they were going to lose the Philippines” to Chinese influence, says Joel Schectman, one of the reporters who broke the story. Schectman says that while it’s impossible to measure the impact of the propaganda effort, it came at a time when the Chinese-made Sinovac shot was the only one available in the Philippines, making distrust of the vaccine “incredibly harmful.”

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

The U.S. military ran a secret anti-vaccination campaign at the height of the pandemic in the Philippines and other nations to sow doubt about COVID vaccines made by China, according to a new investigation by Reuters. The clandestine Pentagon campaign, which began in 2020 under Donald Trump and continued into mid-2021 after Joe Biden took office, relied on fake social media accounts on multiple platforms to target local populations in Southeast Asia and beyond. The campaign also aimed to discredit masks and test kits made in China. “Within the Pentagon, within Washington, there was this fear that they were going to lose the Philippines” to Chinese influence, says Joel Schectman, one of the reporters who broke the story. Schectman says that while it’s impossible to measure the impact of the propaganda effort, it came at a time when the Chinese-made Sinovac shot was the only one available in the Philippines, making distrust of the vaccine “incredibly harmful.”

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Last year, I became obsessed with a plastic cup.

It was a small container that held diced fruit, the type thrown into lunch boxes. And it was the first product I’d seen born of what’s being touted as a cure for a crisis.

Plastic doesn’t break down in nature. If you turned all of what’s been made into cling wrap, it would cover every inch of the globe. It’s piling up, leaching into our water and poisoning our bodies.

Scientists say the key to fixing this is to make less of it; the world churns out 430 million metric tons each year.

But businesses that rely on plastic production, like fossil fuel and chemical companies, have worked since the 1980s to spin the pollution as a failure of waste management — one that can be solved with recycling.

Industry leaders knew then what we know now: Traditional recycling would barely put a dent in the trash heap. It’s hard to transform flimsy candy wrappers into sandwich bags, or to make containers that once held motor oil clean enough for milk.

Now, the industry is heralding nothing short of a miracle: an “advanced”type of recycling known as pyrolysis — “pyro” means fire and “lysis” means separation. It uses heat to break plastic all the way down to its molecular building blocks.

While old-school, “mechanical” recycling yields plastic that’s degraded or contaminated, this type of “chemical” recycling promises plastic that behaves like it’s new, and could usher in what the industry casts as a green revolution: Not only would it save hard-to-recycle plastics like frozen food wrappers from the dumpster, but it would turn them into new products that can replace the old ones and be chemically recycled again and again.

So when three companies used ExxonMobil’s pyrolysis-based technology to successfully conjure up that fruit cup, they announced it to the world.

“This is a significant milestone,” said Printpack, which turned the plastic into cups. The fruit supplier Pacific Coast Producers called it “the most important initiative a consumer-packaged goods company can pursue.”

“ExxonMobil is supporting the circularity of plastics,” the August 2023 news release said, citing a buzzword that implies an infinite loop of using, recycling and reusing.

They were so proud, I hoped they would tell me all about how they made the cup, how many of them existed and where I could buy one.

So began my long — and, well, circular — pursuit of the truth at a time when it really matters.

This year, nearly all of the world’s countries are hammering out a United Nations treaty to deal with the plastic crisis. As they consider limiting production, the industry is making a hard push to shift the conversation to the wonders of chemical recycling. It’s also buying ads during cable news shows as U.S. states consider laws to limit plastic packaging and lobbying federal agencies to loosen the very definition of what it means to recycle.

It’s been selling governments on chemical recycling, with quite a bit of success. American and European regulators have spent tens of millions subsidizing pyrolysis facilities. Half of all U.S. states have eased air pollution rules for the process, which has been found to release carcinogens like benzene and dioxins and give off more greenhouse gases than making plastic from crude oil.

Given the high stakes of this moment, I set out to understand exactly what the world is getting out of this recycling technology. For months, I tracked press releases, interviewed experts, tried to buy plastic made via pyrolysis and learned more than I ever wanted to know about the science of recycled molecules.

Under all the math and engineering, I found an inconvenient truth: Not much is being recycled at all, nor is pyrolysis capable of curbing the plastic crisis.

Not now. Maybe not ever.

Let’s take a closer look at that Printpack press release, which uses convoluted terms to describe the recycled plastic in that fruit cup:

“30% ISCC PLUS certified-circular”

“mass balance free attribution”

It’s easy to conclude the cup was made with 30% recycled plastic — until you break down the numerical sleight of hand that props up that number.

It took interviews with a dozen academics, consultants, environmentalists and engineers to help me do just that.

Stick with me as I unravel it all.

Lesson 1: Most of the old plastic that goes *into* pyrolysis doesn’t actually become new plastic.In traditional recycling, plastic is turned into tiny pellets or flakes, which you can melt again and mold back into recycled plastic products.

Even in a real-life scenario, where bottles have labels and a little bit of juice left in them, most of the plastic products that go into the process find new life.

The numbers are much lower for pyrolysis.

It’s “very, very, very, very difficult” to break down plastic that way, said Steve Jenkins, vice president of chemicals consulting at Wood Mackenzie, an energy and resources analytics firm. “The laws of nature and the laws of physics are trying to stop you.”

Waste is heated until it turns into oil. Part of that oil is composed of a liquid called naphtha, which is essential for making plastic.

There are two ingredients in the naphtha that recyclers want to isolate: propylene and ethylene — gases that can be turned into solid plastics.

To split the naphtha into different chemicals, it’s fed into a machine called a steam cracker. Less than half of what it spits out becomes propylene and ethylene.

This means that if a pyrolysis operator started with 100 pounds of plastic waste, it can expect to end up with 15-20 pounds of reusable plastic. Experts told me the process can yield less if the plastic used is dirty or more if the technology is particularly advanced.

I reached out to several companies to ask how much new plastic their processes actually yield, and none provided numbers. The American Chemistry Council, the nation’s largest plastic lobby, told me that because so many factors impact a company’s yield, it’s impossible to estimate that number for the entire industry.

Lesson 2: The plastic that comes *out of* pyrolysis contains very little recycled material.With mechanical recycling, it’s hard to make plastic that’s 100% recycled; it’s expensive to do, and the process degrades plastic. Recycled pellets are often combined with new pellets to make stuff that’s 25% or 50% recycled, for example.

But far less recycled plastic winds up in products made through pyrolysis.

That’s because the naphtha created using recycled plastic is contaminated. Manufacturers add all kinds of chemicals to make products bend or keep them from degrading in the sun.

Recyclers can overpower them by heavily diluting the recycled naphtha. With what, you ask? Nonrecycled naphtha made from ordinary crude oil!

This is the quiet — and convenient — part of the industry’s revolutionary pyrolysis method: It relies heavily on extracting fossil fuels. At least 90% of the naphtha used in pyrolysis is fossil fuel naphtha. Only then can it be poured into the steam cracker to separate the chemicals that make plastic.

So at the end of the day, nothing that comes out of pyrolysis physically contains more than 10% recycled material (though experts and studies have shown that, in practice, it’s more like 5% or 2%).

Lesson 3: The industry uses mathematical acrobatics to make pyrolysis look like a success.Ten percent doesn’t look very impressive. Some consumers are willing to pay a premium for sustainability, so companies use a form of accounting called mass balance to inflate the recycled-ness of their products. It’s not unlike offset schemes I’ve uncovered that absolve refineries of their carbon emissions and enable mining companies to kill chimpanzees. Industry-affiliated groups like the International Sustainability and Carbon Certification write the rules. (ISCC didn’t respond to requests for comment.)

To see how this works, let’s take a look at what might happen to a batch of recycled naphtha. Let’s say the steam cracker splits the batch into 100 pounds of assorted ingredients.

You’ll get some colorless gasses that are used to make plastic: 13 pounds of propylene and 30 pounds of ethylene. You’ll also wind up with 57 pounds of other chemicals.

Propylene makes sturdy material such as butter tubs; ethylene makes flexible plastics like yogurt pouches. Many of the other chemicals aren’t used to make plastic — some get used to make rubber and paint or are used as fuel.

All of these outputs are technically 10% recycled, since they were made from 10% recycled naphtha. (I’m using this optimistic hypothetical to make the math easy.)

But companies can do a number shuffle to assign all of the recycled value from the butter tubs to the yogurt pouches.

That way they can market the yogurt pouches as 14% recycled (or “circular”), even though nothing has physically changed about the makeup of the pouches.

What’s more, through a method called free attribution, companies can assign the recycled value from other chemicals (even if they would never be turned into plastic) to the yogurt pouches.

Now, the yogurt pouches can be sold as 33% recycled.

There are many flavors of this kind of accounting. Another version of free attribution would allow the company to take that entire 30-pound batch of “33% recycled” pouches and split them even further:

A third of them, 10 pounds, could be labeled 100% recycled — shifting the value of the full batch onto them — so long as the remaining 20 pounds aren’t labeled as recycled at all.

As long as you avoid double counting, Jenkins told me, you can attribute the full value of recycled naphtha to the products that will make the most money. Companies need that financial incentive to recoup the costs of pyrolysis, he said.

But it’s hard to argue that this type of marketing is transparent. Consumers aren’t going to parse through the caveats of a 33% recycled claim or understand how the green technology they’re being sold perpetuates the fossil fuel industry. I posed the critiques to the industry, including environmentalists’ accusations that mass balance is just a fancy way of greenwashing.

The American Chemistry Council told me it’s impossible to know whether a particular ethylene molecule comes from pyrolysis naphtha or fossil fuel naphtha; the compounds produced are “fungible” and can be used for multiple products, like making rubber, solvents and paints that would reduce the amount of new fossil fuels needed. Its statement called mass balance a “well-known methodology” that’s been used by other industries including fair trade coffee, chocolate and renewable energy.

Legislation in the European Union already forbids free attribution, and leaders are debating whether to allow other forms of mass balance. U.S. regulation is far behind that, but as the Federal Trade Commission revises its general guidelines for green marketing, the industry is arguing that mass balance is crucial to the future of advanced recycling. “The science of advanced recycling simply does not support any other approach because the ability to track individual molecules does not readily exist,” said a comment from ExxonMobil.

If you think navigating the ins and outs of pyrolysis is hard, try getting your hands on actual plastic made through it.

It’s not as easy as going to the grocery store. Those water bottles you might see with 100% recycled claims are almost certainly made through traditional recycling. The biggest giveaway is that the labels don’t contain the asterisks or fine print typical of products made through pyrolysis, like “mass balance,” “circular” or “certified.”

When I asked about the fruit cup, ExxonMobil directed me to its partners. Printpack didn’t respond to my inquiries. Pacific Coast Producers told me it was “engaged in a small pilot pack of plastic bowls that contain post-consumer content with materials certified” by third parties, and that it “has made no label claims regarding these cups and is evaluating their use.”

I pressed the American Chemistry Council for other examples.

“Chemical recycling is a proven technology that is already manufacturing products, conserving natural resources, and offering the potential to dramatically improve recycling rates,” said Matthew Kastner, a media relations director. His colleague added that much of the plastic made via pyrolysis is “being used for food- and medical-grade packaging, oftentimes not branded.”

They provided links to products including a Chevron Phillips Chemical announcement about bringing recycled plastic food wrapping to retail stores.

“For competitive reasons,” a Chevron spokesperson declined to discuss brand names, the product’s availability or the amount produced.

In another case, a grocery store chain sold chicken wrapped in plastic made by ExxonMobil’s pyrolysis process. The producers told me they were part of a small project that’s now discontinued.

In the end, I ran down half a dozen claims about products that came out of pyrolysis; each either existed in limited quantities or had its recycled-ness obscured with mass balance caveats.

Then this April, nearly eight months after I’d begun my pursuit, I could barely contain myself when I got my hands on an actual product.

I was at a United Nations treaty negotiation in Ottawa, Ontario, and an industry group had set up a nearby showcase. On display was a case of Heinz baked beans, packaged in “39% recycled plastic*.” (The asterisk took me down an online rabbit hole about certification and circularity. Heinz didn’t respond to my questions.)

This, too, was part of an old trial. The beans were expired.

Pyrolysis is a “fairy tale,” I heard from Neil Tangri, the science and policy director at the environmental justice network Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives. He said he’s been hearing pyrolysis claims since the ’90s but has yet to see proof it works as promised.

“If anyone has cracked the code for a large-scale, efficient and profitable way to turn plastic into plastic,” he said, “every reporter in the world” would get a tour.

If I did get a tour, I wondered, would I even see all of that stubborn, dirty plastic they were supposedly recycling?

The industry’s marketing implied we could soon toss sandwich bags and string cheese wrappers into curbside recycling bins, where they would be diverted to pyrolysis plants. But I grew skeptical as I watched a webinar for ExxonMobil’s pyrolysis-based technology, the kind used to make the fruit cup. The company showed photos of plastic packaging and oil field equipment as examples of its starting material but then mentioned something that made me sit up straight: It was using pre-consumer plastic to “give consistency” to the waste stream.

Chemical plants need consistency, so it’s easier to use plastic that hasn’t been gunked up by consumer use, Jenkins explained.

But plastic waste that had never been touched by consumers, such as industrial scrap found at the edges of factory molds, could easily be recycled the old-fashioned way. Didn’t that negate the need for this more polluting, less efficient process?

I asked ExxonMobil how much post-consumer plastic it was actually using. Catie Tuley, a media relations adviser, said it depends on what’s available. “At the end of the day, advanced recycling allows us to divert plastic waste from landfills and give new life to plastic waste.”

I posed the same question to several other operators. A company in Europe told me it uses “mixed post-consumer, flexible plastic waste” and does not recycle pre-consumer waste.

But this spring at an environmental journalism conference, an American Chemistry Council executive confirmed the industry’s preference for clean plastic as he talked about an Atlanta-based company and its pyrolysis process. My colleague Sharon Lerner asked whether it was sourcing curbside-recycled plastic for pyrolysis.

If Nexus Circular had a “magic wand,” it would, he acknowledged, but right now that kind of waste “isn’t good enough.” He added, “It’s got tomatoes in it.”

(Nexus later confirmed that most of the plastic it used was pre-consumer and about a third was post-consumer, including motor oil containers sourced from car repair shops and bags dropped off at special recycling centers.)

Clean, well-sorted plastic is a valuable commodity. If the chemical recycling industry grows, experts told me, those companies could end up competing with the far more efficient traditional recycling.

To spur that growth, the American Chemistry Council is lobbying for mandates that would require more recycled plastic in packaging; it wants to make sure that chemically recycled plastic counts. “This would create market-driven demand signals,” Kastner told me, and ease the way for large-scale investment in new chemical recycling plants.

I asked Jenkins, the energy industry analyst, to play out this scenario on a larger scale.

Were all of these projects adding up? Could the industry conceivably make enough propylene and ethylene through pyrolysis to replace much of our demand for new plastic?

He looked three years into the future, using his company’s latest figures on global pyrolysis investment, and gave an optimistic assessment.

At best, the world could replace 0.2% of new plastic churned out in a year with products made through pyrolysis.

About the MathOur article is focused on pyrolysis because it’s the most popular form of chemical recycling. Other types of chemical recycling technologies have their own strengths and weaknesses.

There are different variations of pyrolysis, and steam crackers produce a range of ethylene and propylene yields. Companies are secretive about their operations. To estimate the efficiencies of pyrolysis and mass balance, I read dozens of peer-reviewed studies, reports, industry presentations, advertisements and news stories. I also fact checked with a dozen experts who have different opinions on pyrolysis, mass balance and recycling. Some of them, including Jenkins and Anthony Schiavo, senior director at Lux Research, provided estimates of overall yields for companies trying to make plastic. All of that information coalesced around a 15% to 20% yield for conventional pyrolysis processes and 25% to 30% for more advanced technologies. We are showcasing the conventional process because it’s the most common scenario.

We took steps to simplify the math and jargon. For instance, we skipped over the fact that a small amount of the naphtha fed into the steam cracker is consumed as fuel. And we called the fraction of pyrolysis oil that’s suitable for a steam cracker “pyrolysis naphtha”; it is technically a naphtha-like product.

These processes may improve over time as new technologies are developed. But there are hard limits and tradeoffs associated with the nature of steam cracking, the contamination in the feedstock, the type of feedstock used and financial and energy costs.

Graphics and development by Lucas Waldron. Design and development by Anna Donlan. Mollie Simon and Gabriel Sandoval contributed research.

This content originally appeared on ProPublica and was authored by by Lisa Song, Illustrations by Max Gunther, special to ProPublica.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Last year, I became obsessed with a plastic cup.

It was a small container that held diced fruit, the type thrown into lunch boxes. And it was the first product I’d seen born of what’s being touted as a cure for a crisis.

Plastic doesn’t break down in nature. If you turned all of what’s been made into cling wrap, it would cover every inch of the globe. It’s piling up, leaching into our water and poisoning our bodies.

Scientists say the key to fixing this is to make less of it; the world churns out 430 million metric tons each year.

But businesses that rely on plastic production, like fossil fuel and chemical companies, have worked since the 1980s to spin the pollution as a failure of waste management — one that can be solved with recycling.

Industry leaders knew then what we know now: Traditional recycling would barely put a dent in the trash heap. It’s hard to transform flimsy candy wrappers into sandwich bags, or to make containers that once held motor oil clean enough for milk.

Now, the industry is heralding nothing short of a miracle: an “advanced”type of recycling known as pyrolysis — “pyro” means fire and “lysis” means separation. It uses heat to break plastic all the way down to its molecular building blocks.

While old-school, “mechanical” recycling yields plastic that’s degraded or contaminated, this type of “chemical” recycling promises plastic that behaves like it’s new, and could usher in what the industry casts as a green revolution: Not only would it save hard-to-recycle plastics like frozen food wrappers from the dumpster, but it would turn them into new products that can replace the old ones and be chemically recycled again and again.

So when three companies used ExxonMobil’s pyrolysis-based technology to successfully conjure up that fruit cup, they announced it to the world.

“This is a significant milestone,” said Printpack, which turned the plastic into cups. The fruit supplier Pacific Coast Producers called it “the most important initiative a consumer-packaged goods company can pursue.”

“ExxonMobil is supporting the circularity of plastics,” the August 2023 news release said, citing a buzzword that implies an infinite loop of using, recycling and reusing.

They were so proud, I hoped they would tell me all about how they made the cup, how many of them existed and where I could buy one.

So began my long — and, well, circular — pursuit of the truth at a time when it really matters.

This year, nearly all of the world’s countries are hammering out a United Nations treaty to deal with the plastic crisis. As they consider limiting production, the industry is making a hard push to shift the conversation to the wonders of chemical recycling. It’s also buying ads during cable news shows as U.S. states consider laws to limit plastic packaging and lobbying federal agencies to loosen the very definition of what it means to recycle.

It’s been selling governments on chemical recycling, with quite a bit of success. American and European regulators have spent tens of millions subsidizing pyrolysis facilities. Half of all U.S. states have eased air pollution rules for the process, which has been found to release carcinogens like benzene and dioxins and give off more greenhouse gases than making plastic from crude oil.

Given the high stakes of this moment, I set out to understand exactly what the world is getting out of this recycling technology. For months, I tracked press releases, interviewed experts, tried to buy plastic made via pyrolysis and learned more than I ever wanted to know about the science of recycled molecules.

Under all the math and engineering, I found an inconvenient truth: Not much is being recycled at all, nor is pyrolysis capable of curbing the plastic crisis.

Not now. Maybe not ever.

Let’s take a closer look at that Printpack press release, which uses convoluted terms to describe the recycled plastic in that fruit cup:

“30% ISCC PLUS certified-circular”

“mass balance free attribution”

It’s easy to conclude the cup was made with 30% recycled plastic — until you break down the numerical sleight of hand that props up that number.

It took interviews with a dozen academics, consultants, environmentalists and engineers to help me do just that.

Stick with me as I unravel it all.

Lesson 1: Most of the old plastic that goes *into* pyrolysis doesn’t actually become new plastic.In traditional recycling, plastic is turned into tiny pellets or flakes, which you can melt again and mold back into recycled plastic products.

Even in a real-life scenario, where bottles have labels and a little bit of juice left in them, most of the plastic products that go into the process find new life.

The numbers are much lower for pyrolysis.

It’s “very, very, very, very difficult” to break down plastic that way, said Steve Jenkins, vice president of chemicals consulting at Wood Mackenzie, an energy and resources analytics firm. “The laws of nature and the laws of physics are trying to stop you.”

Waste is heated until it turns into oil. Part of that oil is composed of a liquid called naphtha, which is essential for making plastic.

There are two ingredients in the naphtha that recyclers want to isolate: propylene and ethylene — gases that can be turned into solid plastics.

To split the naphtha into different chemicals, it’s fed into a machine called a steam cracker. Less than half of what it spits out becomes propylene and ethylene.

This means that if a pyrolysis operator started with 100 pounds of plastic waste, it can expect to end up with 15-20 pounds of reusable plastic. Experts told me the process can yield less if the plastic used is dirty or more if the technology is particularly advanced.

I reached out to several companies to ask how much new plastic their processes actually yield, and none provided numbers. The American Chemistry Council, the nation’s largest plastic lobby, told me that because so many factors impact a company’s yield, it’s impossible to estimate that number for the entire industry.

Lesson 2: The plastic that comes *out of* pyrolysis contains very little recycled material.With mechanical recycling, it’s hard to make plastic that’s 100% recycled; it’s expensive to do, and the process degrades plastic. Recycled pellets are often combined with new pellets to make stuff that’s 25% or 50% recycled, for example.

But far less recycled plastic winds up in products made through pyrolysis.

That’s because the naphtha created using recycled plastic is contaminated. Manufacturers add all kinds of chemicals to make products bend or keep them from degrading in the sun.

Recyclers can overpower them by heavily diluting the recycled naphtha. With what, you ask? Nonrecycled naphtha made from ordinary crude oil!

This is the quiet — and convenient — part of the industry’s revolutionary pyrolysis method: It relies heavily on extracting fossil fuels. At least 90% of the naphtha used in pyrolysis is fossil fuel naphtha. Only then can it be poured into the steam cracker to separate the chemicals that make plastic.

So at the end of the day, nothing that comes out of pyrolysis physically contains more than 10% recycled material (though experts and studies have shown that, in practice, it’s more like 5% or 2%).

Lesson 3: The industry uses mathematical acrobatics to make pyrolysis look like a success.Ten percent doesn’t look very impressive. Some consumers are willing to pay a premium for sustainability, so companies use a form of accounting called mass balance to inflate the recycled-ness of their products. It’s not unlike offset schemes I’ve uncovered that absolve refineries of their carbon emissions and enable mining companies to kill chimpanzees. Industry-affiliated groups like the International Sustainability and Carbon Certification write the rules. (ISCC didn’t respond to requests for comment.)

To see how this works, let’s take a look at what might happen to a batch of recycled naphtha. Let’s say the steam cracker splits the batch into 100 pounds of assorted ingredients.

You’ll get some colorless gasses that are used to make plastic: 13 pounds of propylene and 30 pounds of ethylene. You’ll also wind up with 57 pounds of other chemicals.

Propylene makes sturdy material such as butter tubs; ethylene makes flexible plastics like yogurt pouches. Many of the other chemicals aren’t used to make plastic — some get used to make rubber and paint or are used as fuel.

All of these outputs are technically 10% recycled, since they were made from 10% recycled naphtha. (I’m using this optimistic hypothetical to make the math easy.)

But companies can do a number shuffle to assign all of the recycled value from the butter tubs to the yogurt pouches.

That way they can market the yogurt pouches as 14% recycled (or “circular”), even though nothing has physically changed about the makeup of the pouches.

What’s more, through a method called free attribution, companies can assign the recycled value from other chemicals (even if they would never be turned into plastic) to the yogurt pouches.

Now, the yogurt pouches can be sold as 33% recycled.

There are many flavors of this kind of accounting. Another version of free attribution would allow the company to take that entire 30-pound batch of “33% recycled” pouches and split them even further:

A third of them, 10 pounds, could be labeled 100% recycled — shifting the value of the full batch onto them — so long as the remaining 20 pounds aren’t labeled as recycled at all.

As long as you avoid double counting, Jenkins told me, you can attribute the full value of recycled naphtha to the products that will make the most money. Companies need that financial incentive to recoup the costs of pyrolysis, he said.

But it’s hard to argue that this type of marketing is transparent. Consumers aren’t going to parse through the caveats of a 33% recycled claim or understand how the green technology they’re being sold perpetuates the fossil fuel industry. I posed the critiques to the industry, including environmentalists’ accusations that mass balance is just a fancy way of greenwashing.

The American Chemistry Council told me it’s impossible to know whether a particular ethylene molecule comes from pyrolysis naphtha or fossil fuel naphtha; the compounds produced are “fungible” and can be used for multiple products, like making rubber, solvents and paints that would reduce the amount of new fossil fuels needed. Its statement called mass balance a “well-known methodology” that’s been used by other industries including fair trade coffee, chocolate and renewable energy.

Legislation in the European Union already forbids free attribution, and leaders are debating whether to allow other forms of mass balance. U.S. regulation is far behind that, but as the Federal Trade Commission revises its general guidelines for green marketing, the industry is arguing that mass balance is crucial to the future of advanced recycling. “The science of advanced recycling simply does not support any other approach because the ability to track individual molecules does not readily exist,” said a comment from ExxonMobil.

If you think navigating the ins and outs of pyrolysis is hard, try getting your hands on actual plastic made through it.

It’s not as easy as going to the grocery store. Those water bottles you might see with 100% recycled claims are almost certainly made through traditional recycling. The biggest giveaway is that the labels don’t contain the asterisks or fine print typical of products made through pyrolysis, like “mass balance,” “circular” or “certified.”

When I asked about the fruit cup, ExxonMobil directed me to its partners. Printpack didn’t respond to my inquiries. Pacific Coast Producers told me it was “engaged in a small pilot pack of plastic bowls that contain post-consumer content with materials certified” by third parties, and that it “has made no label claims regarding these cups and is evaluating their use.”

I pressed the American Chemistry Council for other examples.

“Chemical recycling is a proven technology that is already manufacturing products, conserving natural resources, and offering the potential to dramatically improve recycling rates,” said Matthew Kastner, a media relations director. His colleague added that much of the plastic made via pyrolysis is “being used for food- and medical-grade packaging, oftentimes not branded.”

They provided links to products including a Chevron Phillips Chemical announcement about bringing recycled plastic food wrapping to retail stores.

“For competitive reasons,” a Chevron spokesperson declined to discuss brand names, the product’s availability or the amount produced.

In another case, a grocery store chain sold chicken wrapped in plastic made by ExxonMobil’s pyrolysis process. The producers told me they were part of a small project that’s now discontinued.

In the end, I ran down half a dozen claims about products that came out of pyrolysis; each either existed in limited quantities or had its recycled-ness obscured with mass balance caveats.

Then this April, nearly eight months after I’d begun my pursuit, I could barely contain myself when I got my hands on an actual product.

I was at a United Nations treaty negotiation in Ottawa, Ontario, and an industry group had set up a nearby showcase. On display was a case of Heinz baked beans, packaged in “39% recycled plastic*.” (The asterisk took me down an online rabbit hole about certification and circularity. Heinz didn’t respond to my questions.)

This, too, was part of an old trial. The beans were expired.

Pyrolysis is a “fairy tale,” I heard from Neil Tangri, the science and policy director at the environmental justice network Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives. He said he’s been hearing pyrolysis claims since the ’90s but has yet to see proof it works as promised.

“If anyone has cracked the code for a large-scale, efficient and profitable way to turn plastic into plastic,” he said, “every reporter in the world” would get a tour.

If I did get a tour, I wondered, would I even see all of that stubborn, dirty plastic they were supposedly recycling?

The industry’s marketing implied we could soon toss sandwich bags and string cheese wrappers into curbside recycling bins, where they would be diverted to pyrolysis plants. But I grew skeptical as I watched a webinar for ExxonMobil’s pyrolysis-based technology, the kind used to make the fruit cup. The company showed photos of plastic packaging and oil field equipment as examples of its starting material but then mentioned something that made me sit up straight: It was using pre-consumer plastic to “give consistency” to the waste stream.

Chemical plants need consistency, so it’s easier to use plastic that hasn’t been gunked up by consumer use, Jenkins explained.

But plastic waste that had never been touched by consumers, such as industrial scrap found at the edges of factory molds, could easily be recycled the old-fashioned way. Didn’t that negate the need for this more polluting, less efficient process?

I asked ExxonMobil how much post-consumer plastic it was actually using. Catie Tuley, a media relations adviser, said it depends on what’s available. “At the end of the day, advanced recycling allows us to divert plastic waste from landfills and give new life to plastic waste.”

I posed the same question to several other operators. A company in Europe told me it uses “mixed post-consumer, flexible plastic waste” and does not recycle pre-consumer waste.

But this spring at an environmental journalism conference, an American Chemistry Council executive confirmed the industry’s preference for clean plastic as he talked about an Atlanta-based company and its pyrolysis process. My colleague Sharon Lerner asked whether it was sourcing curbside-recycled plastic for pyrolysis.

If Nexus Circular had a “magic wand,” it would, he acknowledged, but right now that kind of waste “isn’t good enough.” He added, “It’s got tomatoes in it.”

(Nexus later confirmed that most of the plastic it used was pre-consumer and about a third was post-consumer, including motor oil containers sourced from car repair shops and bags dropped off at special recycling centers.)

Clean, well-sorted plastic is a valuable commodity. If the chemical recycling industry grows, experts told me, those companies could end up competing with the far more efficient traditional recycling.

To spur that growth, the American Chemistry Council is lobbying for mandates that would require more recycled plastic in packaging; it wants to make sure that chemically recycled plastic counts. “This would create market-driven demand signals,” Kastner told me, and ease the way for large-scale investment in new chemical recycling plants.

I asked Jenkins, the energy industry analyst, to play out this scenario on a larger scale.

Were all of these projects adding up? Could the industry conceivably make enough propylene and ethylene through pyrolysis to replace much of our demand for new plastic?

He looked three years into the future, using his company’s latest figures on global pyrolysis investment, and gave an optimistic assessment.

At best, the world could replace 0.2% of new plastic churned out in a year with products made through pyrolysis.

About the MathOur article is focused on pyrolysis because it’s the most popular form of chemical recycling. Other types of chemical recycling technologies have their own strengths and weaknesses.

There are different variations of pyrolysis, and steam crackers produce a range of ethylene and propylene yields. Companies are secretive about their operations. To estimate the efficiencies of pyrolysis and mass balance, I read dozens of peer-reviewed studies, reports, industry presentations, advertisements and news stories. I also fact checked with a dozen experts who have different opinions on pyrolysis, mass balance and recycling. Some of them, including Jenkins and Anthony Schiavo, senior director at Lux Research, provided estimates of overall yields for companies trying to make plastic. All of that information coalesced around a 15% to 20% yield for conventional pyrolysis processes and 25% to 30% for more advanced technologies. We are showcasing the conventional process because it’s the most common scenario.

We took steps to simplify the math and jargon. For instance, we skipped over the fact that a small amount of the naphtha fed into the steam cracker is consumed as fuel. And we called the fraction of pyrolysis oil that’s suitable for a steam cracker “pyrolysis naphtha”; it is technically a naphtha-like product.

These processes may improve over time as new technologies are developed. But there are hard limits and tradeoffs associated with the nature of steam cracking, the contamination in the feedstock, the type of feedstock used and financial and energy costs.

Graphics and development by Lucas Waldron. Design and development by Anna Donlan. Mollie Simon and Gabriel Sandoval contributed research.

This content originally appeared on ProPublica and was authored by by Lisa Song, Illustrations by Max Gunther, special to ProPublica.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Last year, I became obsessed with a plastic cup.

It was a small container that held diced fruit, the type thrown into lunch boxes. And it was the first product I’d seen born of what’s being touted as a cure for a crisis.

Plastic doesn’t break down in nature. If you turned all of what’s been made into cling wrap, it would cover every inch of the globe. It’s piling up, leaching into our water and poisoning our bodies.

Scientists say the key to fixing this is to make less of it; the world churns out 430 million metric tons each year.

But businesses that rely on plastic production, like fossil fuel and chemical companies, have worked since the 1980s to spin the pollution as a failure of waste management — one that can be solved with recycling.

Industry leaders knew then what we know now: Traditional recycling would barely put a dent in the trash heap. It’s hard to transform flimsy candy wrappers into sandwich bags, or to make containers that once held motor oil clean enough for milk.

Now, the industry is heralding nothing short of a miracle: an “advanced”type of recycling known as pyrolysis — “pyro” means fire and “lysis” means separation. It uses heat to break plastic all the way down to its molecular building blocks.

While old-school, “mechanical” recycling yields plastic that’s degraded or contaminated, this type of “chemical” recycling promises plastic that behaves like it’s new, and could usher in what the industry casts as a green revolution: Not only would it save hard-to-recycle plastics like frozen food wrappers from the dumpster, but it would turn them into new products that can replace the old ones and be chemically recycled again and again.

So when three companies used ExxonMobil’s pyrolysis-based technology to successfully conjure up that fruit cup, they announced it to the world.

“This is a significant milestone,” said Printpack, which turned the plastic into cups. The fruit supplier Pacific Coast Producers called it “the most important initiative a consumer-packaged goods company can pursue.”

“ExxonMobil is supporting the circularity of plastics,” the August 2023 news release said, citing a buzzword that implies an infinite loop of using, recycling and reusing.

They were so proud, I hoped they would tell me all about how they made the cup, how many of them existed and where I could buy one.

So began my long — and, well, circular — pursuit of the truth at a time when it really matters.

This year, nearly all of the world’s countries are hammering out a United Nations treaty to deal with the plastic crisis. As they consider limiting production, the industry is making a hard push to shift the conversation to the wonders of chemical recycling. It’s also buying ads during cable news shows as U.S. states consider laws to limit plastic packaging and lobbying federal agencies to loosen the very definition of what it means to recycle.

It’s been selling governments on chemical recycling, with quite a bit of success. American and European regulators have spent tens of millions subsidizing pyrolysis facilities. Half of all U.S. states have eased air pollution rules for the process, which has been found to release carcinogens like benzene and dioxins and give off more greenhouse gases than making plastic from crude oil.

Given the high stakes of this moment, I set out to understand exactly what the world is getting out of this recycling technology. For months, I tracked press releases, interviewed experts, tried to buy plastic made via pyrolysis and learned more than I ever wanted to know about the science of recycled molecules.

Under all the math and engineering, I found an inconvenient truth: Not much is being recycled at all, nor is pyrolysis capable of curbing the plastic crisis.

Not now. Maybe not ever.

Let’s take a closer look at that Printpack press release, which uses convoluted terms to describe the recycled plastic in that fruit cup:

“30% ISCC PLUS certified-circular”

“mass balance free attribution”

It’s easy to conclude the cup was made with 30% recycled plastic — until you break down the numerical sleight of hand that props up that number.

It took interviews with a dozen academics, consultants, environmentalists and engineers to help me do just that.

Stick with me as I unravel it all.

Lesson 1: Most of the old plastic that goes *into* pyrolysis doesn’t actually become new plastic.In traditional recycling, plastic is turned into tiny pellets or flakes, which you can melt again and mold back into recycled plastic products.

Even in a real-life scenario, where bottles have labels and a little bit of juice left in them, most of the plastic products that go into the process find new life.

The numbers are much lower for pyrolysis.

It’s “very, very, very, very difficult” to break down plastic that way, said Steve Jenkins, vice president of chemicals consulting at Wood Mackenzie, an energy and resources analytics firm. “The laws of nature and the laws of physics are trying to stop you.”

Waste is heated until it turns into oil. Part of that oil is composed of a liquid called naphtha, which is essential for making plastic.

There are two ingredients in the naphtha that recyclers want to isolate: propylene and ethylene — gases that can be turned into solid plastics.

To split the naphtha into different chemicals, it’s fed into a machine called a steam cracker. Less than half of what it spits out becomes propylene and ethylene.

This means that if a pyrolysis operator started with 100 pounds of plastic waste, it can expect to end up with 15-20 pounds of reusable plastic. Experts told me the process can yield less if the plastic used is dirty or more if the technology is particularly advanced.

I reached out to several companies to ask how much new plastic their processes actually yield, and none provided numbers. The American Chemistry Council, the nation’s largest plastic lobby, told me that because so many factors impact a company’s yield, it’s impossible to estimate that number for the entire industry.

Lesson 2: The plastic that comes *out of* pyrolysis contains very little recycled material.With mechanical recycling, it’s hard to make plastic that’s 100% recycled; it’s expensive to do, and the process degrades plastic. Recycled pellets are often combined with new pellets to make stuff that’s 25% or 50% recycled, for example.

But far less recycled plastic winds up in products made through pyrolysis.

That’s because the naphtha created using recycled plastic is contaminated. Manufacturers add all kinds of chemicals to make products bend or keep them from degrading in the sun.

Recyclers can overpower them by heavily diluting the recycled naphtha. With what, you ask? Nonrecycled naphtha made from ordinary crude oil!

This is the quiet — and convenient — part of the industry’s revolutionary pyrolysis method: It relies heavily on extracting fossil fuels. At least 90% of the naphtha used in pyrolysis is fossil fuel naphtha. Only then can it be poured into the steam cracker to separate the chemicals that make plastic.

So at the end of the day, nothing that comes out of pyrolysis physically contains more than 10% recycled material (though experts and studies have shown that, in practice, it’s more like 5% or 2%).

Lesson 3: The industry uses mathematical acrobatics to make pyrolysis look like a success.Ten percent doesn’t look very impressive. Some consumers are willing to pay a premium for sustainability, so companies use a form of accounting called mass balance to inflate the recycled-ness of their products. It’s not unlike offset schemes I’ve uncovered that absolve refineries of their carbon emissions and enable mining companies to kill chimpanzees. Industry-affiliated groups like the International Sustainability and Carbon Certification write the rules. (ISCC didn’t respond to requests for comment.)

To see how this works, let’s take a look at what might happen to a batch of recycled naphtha. Let’s say the steam cracker splits the batch into 100 pounds of assorted ingredients.

You’ll get some colorless gasses that are used to make plastic: 13 pounds of propylene and 30 pounds of ethylene. You’ll also wind up with 57 pounds of other chemicals.

Propylene makes sturdy material such as butter tubs; ethylene makes flexible plastics like yogurt pouches. Many of the other chemicals aren’t used to make plastic — some get used to make rubber and paint or are used as fuel.

All of these outputs are technically 10% recycled, since they were made from 10% recycled naphtha. (I’m using this optimistic hypothetical to make the math easy.)

But companies can do a number shuffle to assign all of the recycled value from the butter tubs to the yogurt pouches.

That way they can market the yogurt pouches as 14% recycled (or “circular”), even though nothing has physically changed about the makeup of the pouches.

What’s more, through a method called free attribution, companies can assign the recycled value from other chemicals (even if they would never be turned into plastic) to the yogurt pouches.

Now, the yogurt pouches can be sold as 33% recycled.

There are many flavors of this kind of accounting. Another version of free attribution would allow the company to take that entire 30-pound batch of “33% recycled” pouches and split them even further:

A third of them, 10 pounds, could be labeled 100% recycled — shifting the value of the full batch onto them — so long as the remaining 20 pounds aren’t labeled as recycled at all.

As long as you avoid double counting, Jenkins told me, you can attribute the full value of recycled naphtha to the products that will make the most money. Companies need that financial incentive to recoup the costs of pyrolysis, he said.

But it’s hard to argue that this type of marketing is transparent. Consumers aren’t going to parse through the caveats of a 33% recycled claim or understand how the green technology they’re being sold perpetuates the fossil fuel industry. I posed the critiques to the industry, including environmentalists’ accusations that mass balance is just a fancy way of greenwashing.

The American Chemistry Council told me it’s impossible to know whether a particular ethylene molecule comes from pyrolysis naphtha or fossil fuel naphtha; the compounds produced are “fungible” and can be used for multiple products, like making rubber, solvents and paints that would reduce the amount of new fossil fuels needed. Its statement called mass balance a “well-known methodology” that’s been used by other industries including fair trade coffee, chocolate and renewable energy.

Legislation in the European Union already forbids free attribution, and leaders are debating whether to allow other forms of mass balance. U.S. regulation is far behind that, but as the Federal Trade Commission revises its general guidelines for green marketing, the industry is arguing that mass balance is crucial to the future of advanced recycling. “The science of advanced recycling simply does not support any other approach because the ability to track individual molecules does not readily exist,” said a comment from ExxonMobil.

If you think navigating the ins and outs of pyrolysis is hard, try getting your hands on actual plastic made through it.

It’s not as easy as going to the grocery store. Those water bottles you might see with 100% recycled claims are almost certainly made through traditional recycling. The biggest giveaway is that the labels don’t contain the asterisks or fine print typical of products made through pyrolysis, like “mass balance,” “circular” or “certified.”

When I asked about the fruit cup, ExxonMobil directed me to its partners. Printpack didn’t respond to my inquiries. Pacific Coast Producers told me it was “engaged in a small pilot pack of plastic bowls that contain post-consumer content with materials certified” by third parties, and that it “has made no label claims regarding these cups and is evaluating their use.”

I pressed the American Chemistry Council for other examples.

“Chemical recycling is a proven technology that is already manufacturing products, conserving natural resources, and offering the potential to dramatically improve recycling rates,” said Matthew Kastner, a media relations director. His colleague added that much of the plastic made via pyrolysis is “being used for food- and medical-grade packaging, oftentimes not branded.”

They provided links to products including a Chevron Phillips Chemical announcement about bringing recycled plastic food wrapping to retail stores.

“For competitive reasons,” a Chevron spokesperson declined to discuss brand names, the product’s availability or the amount produced.

In another case, a grocery store chain sold chicken wrapped in plastic made by ExxonMobil’s pyrolysis process. The producers told me they were part of a small project that’s now discontinued.

In the end, I ran down half a dozen claims about products that came out of pyrolysis; each either existed in limited quantities or had its recycled-ness obscured with mass balance caveats.

Then this April, nearly eight months after I’d begun my pursuit, I could barely contain myself when I got my hands on an actual product.

I was at a United Nations treaty negotiation in Ottawa, Ontario, and an industry group had set up a nearby showcase. On display was a case of Heinz baked beans, packaged in “39% recycled plastic*.” (The asterisk took me down an online rabbit hole about certification and circularity. Heinz didn’t respond to my questions.)

This, too, was part of an old trial. The beans were expired.

Pyrolysis is a “fairy tale,” I heard from Neil Tangri, the science and policy director at the environmental justice network Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives. He said he’s been hearing pyrolysis claims since the ’90s but has yet to see proof it works as promised.

“If anyone has cracked the code for a large-scale, efficient and profitable way to turn plastic into plastic,” he said, “every reporter in the world” would get a tour.

If I did get a tour, I wondered, would I even see all of that stubborn, dirty plastic they were supposedly recycling?

The industry’s marketing implied we could soon toss sandwich bags and string cheese wrappers into curbside recycling bins, where they would be diverted to pyrolysis plants. But I grew skeptical as I watched a webinar for ExxonMobil’s pyrolysis-based technology, the kind used to make the fruit cup. The company showed photos of plastic packaging and oil field equipment as examples of its starting material but then mentioned something that made me sit up straight: It was using pre-consumer plastic to “give consistency” to the waste stream.

Chemical plants need consistency, so it’s easier to use plastic that hasn’t been gunked up by consumer use, Jenkins explained.

But plastic waste that had never been touched by consumers, such as industrial scrap found at the edges of factory molds, could easily be recycled the old-fashioned way. Didn’t that negate the need for this more polluting, less efficient process?

I asked ExxonMobil how much post-consumer plastic it was actually using. Catie Tuley, a media relations adviser, said it depends on what’s available. “At the end of the day, advanced recycling allows us to divert plastic waste from landfills and give new life to plastic waste.”

I posed the same question to several other operators. A company in Europe told me it uses “mixed post-consumer, flexible plastic waste” and does not recycle pre-consumer waste.

But this spring at an environmental journalism conference, an American Chemistry Council executive confirmed the industry’s preference for clean plastic as he talked about an Atlanta-based company and its pyrolysis process. My colleague Sharon Lerner asked whether it was sourcing curbside-recycled plastic for pyrolysis.

If Nexus Circular had a “magic wand,” it would, he acknowledged, but right now that kind of waste “isn’t good enough.” He added, “It’s got tomatoes in it.”

(Nexus later confirmed that most of the plastic it used was pre-consumer and about a third was post-consumer, including motor oil containers sourced from car repair shops and bags dropped off at special recycling centers.)

Clean, well-sorted plastic is a valuable commodity. If the chemical recycling industry grows, experts told me, those companies could end up competing with the far more efficient traditional recycling.

To spur that growth, the American Chemistry Council is lobbying for mandates that would require more recycled plastic in packaging; it wants to make sure that chemically recycled plastic counts. “This would create market-driven demand signals,” Kastner told me, and ease the way for large-scale investment in new chemical recycling plants.

I asked Jenkins, the energy industry analyst, to play out this scenario on a larger scale.

Were all of these projects adding up? Could the industry conceivably make enough propylene and ethylene through pyrolysis to replace much of our demand for new plastic?

He looked three years into the future, using his company’s latest figures on global pyrolysis investment, and gave an optimistic assessment.

At best, the world could replace 0.2% of new plastic churned out in a year with products made through pyrolysis.

About the MathOur article is focused on pyrolysis because it’s the most popular form of chemical recycling. Other types of chemical recycling technologies have their own strengths and weaknesses.

There are different variations of pyrolysis, and steam crackers produce a range of ethylene and propylene yields. Companies are secretive about their operations. To estimate the efficiencies of pyrolysis and mass balance, I read dozens of peer-reviewed studies, reports, industry presentations, advertisements and news stories. I also fact checked with a dozen experts who have different opinions on pyrolysis, mass balance and recycling. Some of them, including Jenkins and Anthony Schiavo, senior director at Lux Research, provided estimates of overall yields for companies trying to make plastic. All of that information coalesced around a 15% to 20% yield for conventional pyrolysis processes and 25% to 30% for more advanced technologies. We are showcasing the conventional process because it’s the most common scenario.

We took steps to simplify the math and jargon. For instance, we skipped over the fact that a small amount of the naphtha fed into the steam cracker is consumed as fuel. And we called the fraction of pyrolysis oil that’s suitable for a steam cracker “pyrolysis naphtha”; it is technically a naphtha-like product.

These processes may improve over time as new technologies are developed. But there are hard limits and tradeoffs associated with the nature of steam cracking, the contamination in the feedstock, the type of feedstock used and financial and energy costs.

Graphics and development by Lucas Waldron. Design and development by Anna Donlan. Mollie Simon and Gabriel Sandoval contributed research.

This content originally appeared on ProPublica and was authored by by Lisa Song, Illustrations by Max Gunther, special to ProPublica.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on International Rescue Committee and was authored by International Rescue Committee.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Comprehensive coverage of the day’s news with a focus on war and peace; social, environmental and economic justice.

The post The Pacifica Evening News, Weekdays – June 19, 2024. Boeing victims relatives call on federal government to fine the company $25 billion over two crashes. appeared first on KPFA.

This content originally appeared on KPFA – The Pacifica Evening News, Weekdays and was authored by KPFA.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

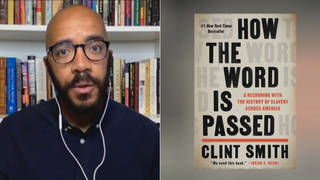

We feature a special broadcast marking the Juneteenth federal holiday that commemorates the day in 1865 when enslaved people in Galveston, Texas, learned of their freedom more than two years after the Emancipation Proclamation. We begin with our 2021 interview with historian Clint Smith, originally aired a day after President Biden signed legislation to make Juneteenth the first new federal holiday since Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Day. Smith is the author of How the Word Is Passed: A Reckoning with the History of Slavery Across America. “When I think of Juneteenth, part of what I think about is the both/andedness of it,” Smith says, “that it is this moment in which we mourn the fact that freedom was kept from hundreds of thousands of enslaved people for years and for months after it had been attained by them, and then, at the same time, celebrating the end of one of the most egregious things that this country has ever done.” Smith says he recognizes the federal holiday marking Juneteenth as a symbol, “but it is clearly not enough.”

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Photograph by Nathaniel St. Clair

As the story of Juneteenth is told by modern-day historians, enslaved Black people were freed by laws, not combat.

Union Gen. Gordon Granger said as much when he read General Order No. 3 in Galveston, Texas, in front of enslaved people who were among the last to learn of their legal freedom.

According to the order, the law promised the “absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves.”

But the new laws guaranteeing legal protections for equal rights – starting with the Emancipation Proclamation in January 1863 and followed by the ratification of the 13th, 14th and 15th amendments after the U.S. Civil War had ended in April 1865 – did not eliminate the influence of slavery on the laws.

The legacy of slavery is still enshrined in thousands of judicial opinions and briefs that are cited today by American judges and lawyers in cases involving everything from property rights to criminal law.

For example, in 2016 a judge on the 3rd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals cited Prigg v. Pennsylvania, an 1842 U.S. Supreme Court case that held that a state could not provide legal protections for alleged fugitive slaves. The judge cited that case to explain the limits of congressional power to limit gambling in college sports.

In 2013, a judge on the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals cited Prigg for similar reasons. In that case, involving challenges to an Indian tribe’s acquisition of land, the judge relied on Prigg to explain how to interpret a federal statute.

Neither of these judges acknowledged or addressed the origins of the Prigg v. Pennsylvania case.

That is not unusual.

What I have learned by researching these slave cases is that the vast majority of judges do not acknowledge that the cases they cite involve the enslaved. They also almost never consider how slavery may have shaped legal rules.

The Citing Slavery Project

To place these laws in historical context for modern-day usage and encourage judges and lawyers to address slavery’s influence on the law, I started the Citing Slavery Project in 2020. Since then, my team of students and I have identified more than 12,000 cases involving enslaved people and more than 40,000 cases that cite those cases.

We have found dozens of citations of slave cases in the 2010s. Such citations appear in rulings from the U.S. Supreme Court and in state courts across the country. Citation by lawyers in briefs is even more prevalent.

An ethical obligation?

Addressing slavery’s legal legacy is not just an issue for historians.

It is also an ethical issue for legal professionals. The code of conduct for U.S. judges recognizes that “an independent and honorable judiciary is indispensable to justice in our society.” The code further calls for judges to “act at all times in a manner that promotes public confidence in the integrity … of the judiciary.”

Lawyers share in this obligation.

The American Bar Association notes the profession’s “special responsibility for the quality of justice.” It also calls for lawyers to further “the public’s understanding of and confidence in the rule of law and the justice system.”

Such actions are particularly important because of the rising importance of the Supreme Court’s history-and-tradition test, which uses analysis of historical traditions to determine modern constitutional rights. Courts risk undermining their legitimacy by paying attention to some legal legacies while ignoring others.

It is my belief that lawyers and judges must confront slavery’s legacy in order to atone for the legal profession’s past actions and to fulfill their ethical duties to ensure confidence in our legal system.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The post US Laws Created During Slavery are Still on the Books appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

This content originally appeared on CounterPunch.org and was authored by Justin Simard.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by Radio Free Asia.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

When Belete Kassa’s friend and news show co-host Belaye Manaye was arrested in November 2023 and taken to the remote Awash Arba military camp known as the “Guantanamo of the desert,” Belete feared that he might be next.

The two men co-founded the YouTube-based channel Ethio News in 2020, which had reported extensively on a conflict that broke out between federal forces and the Fano militia in the populous Amhara region in April 2023, a risky move in a country with a history of stifling independent reporting.

Belay was swept up in a crackdown against the press after the government declared a state of emergency in August 2023 in response to the conflict.

After months in hiding, Belete decided to flee when he heard from a relative that the government had issued a warrant for his arrest. CPJ was unable to confirm whether such an order was issued.

“Freedom of expression in Ethiopia has not only died; it has been buried,” Belete said in his March 15 farewell post on Facebook. “Leaving behind a colleague in a desert detention facility, as well as one’s family and country, to seek asylum, is immensely painful.” (Belaye and others have been released this month after the state of emergency expired.)

Belete’s path into exile is one that has been trod by dozens of other Ethiopian journalists who have been forced to flee harassment and persecution in a country where the government has long maintained a firm grip on the media. Over the decades, CPJ has documented waves of repression and exile tied to reporting on events like protests after the 2005 parliamentary election and censorship of independent media and bloggers ahead of the 2015 vote.

In 2018, the Ethiopian press enjoyed a short-lived honeymoon when all previously detained journalists were released and hundreds of websites unblocked after Abiy Ahmed became prime minister.

But with the 2020 to 2022 civil war between rebels from the Tigray region and the federal government, followed by the Amhara conflict in 2023, CPJ has documented a rapid return to a harsh media environment, characterized by arbitrary detentions and the expulsion of international journalists.

CPJ is aware of at least 54 Ethiopian journalists and media workers who have gone into exile since 2020, and has provided at least 30 of them with emergency assistance. Most of the journalists fled to neighboring African countries, while a few are in Europe and North America. In May and June 2024, CPJ spoke to some of these exiled journalists about their experiences. Most asked CPJ not to reveal how they escaped Ethiopia or their whereabouts and some spoke on condition of anonymity, citing fears for their safety or that of family left behind.

CPJ’s request for comment to government spokesperson Legesse Tulu via messaging app and an email to the office of the prime minister did not receive any response.

Under ‘house arrest’ due to death threats

Guyo Wariyo, a journalist with the satellite broadcaster Oromia Media Network was detained for several weeks in 2020 as the government sought to quell protests over the killing of ethnic Oromo singer Hachalu Hundessa. Authorities sought to link the musician’s assassination with Guyo’s interview with him the previous week, which included questions about the singer’s political opinions.

Following his release, Guyo wanted to get out of the country but leaving was not easy. Guyo said that the first three times he went to Addis Ababa’s Bole International Airport, National Intelligence and Security Service agents refused to let him board, saying his name was on a government list of individuals barred from leaving Ethiopia.

Guyo eventually left in late 2020. But, more than three years later, he still feels unsafe.

In exile, Guyo says he has received several death threats from individuals that he believes are affiliated with the Ethiopian government, via social media as well as local and international phone numbers. One of the callers even named the neighborhood where he lives.

“I can describe my situation as ‘house arrest,’” said Guyo, who rarely goes out or speaks to friends and family back home in case their conversations are monitored.

Transnational repression is a growing risk globally. Ethiopia has long reached across borders to seize refugees and asylum seekers in neighboring Kenya, Uganda, Somalia, and South Sudan, and targeted those further afield, including with spyware.

Journalists who spoke to CPJ said they fear transnational repression, citing the 2023 forcible return of The Voice of Amhara’s Gobeze Sisay from Djibouti to face terrorism charges. He remains in prison, awaiting trial and a potential death penalty.

“We know historically that Ethiopian intelligence have been active in East Africa and there is a history of fleeing people being attacked here in Kenya,” Nduko o’Matigere, Head of Africa Region at PEN International, the global writers’ association that advocates for freedom of expression, told CPJ.

Several of the journalists exiled in Africa told CPJ that they did not feel their host countries could protect them from Ethiopian security agents.

“The shadow of fear and threat is always present,” said one reporter, describing the brief period he lived in East Africa before resettling in the United States.

‘We became very scared’

Woldegiorgis Ghebrehiwet Teklay felt at risk in Kenya, after he fled there in December 2020 following the arrest of a colleague at the now-defunct Awlo Media Center.

As with Guyo, Woldegiorgis’s initial attempt to leave via Addis Ababa failed. Airport security personnel questioned him about his work and ethnicity and accused him of betraying his country with his journalism, before ordering him to return home, to wait for about a week amid investigations.

When Woldegiorgis finally reached the Kenyan capital, he partnered with other exiled Ethiopian journalists to set up Axumite Media. But between November 2021 and February 2022, Axumite was forced to slow down its operations, reducing the frequency of publication and visibility of its journalists as it was hit by financial and security concerns, especially after two men abducted an Ethiopian businessman from his car during Nairobi’s evening rush hour.

“It might be a coincidence but after that businessman was abducted on the street we became very scared,” said Woldegiorgis who moved to Germany the following year on a scholarship for at-risk academics and relaunched the outlet as Yabele Media.

‘An enemy of the state’

Tesfa-Alem Tekle was reporting for the Nairobi-based Nation Media Group when he had to flee in 2022, after being detained for nearly three months on suspicion of having links with Tigrayan rebels.

He kept contributing to the Nation Media Group’s The EastAfrican weekly newspaper in exile until 2023, when a death threat was slipped under his door.

“Stop disseminating in the media messages which humiliate and tarnish our country and our government’s image,” said the threat, written in Amharic, which CPJ reviewed. “If you continue being an enemy of the state, we warn you for the last time that a once-and-for-all action will be taken against you.”

Tesfa-Alem moved houses, reported the threat to the police, and hoped he would soon be offered safety in another country. But more than two years after going to exile, he remains in limbo, waiting to hear the outcome of his application for resettlement.

Last year, only 158,700 refugees worldwide were resettled in third countries, representing just a fraction of the need, according to the U.N. refugee agency UNHCR; that included 2,289 Ethiopians, said UNHCR global spokesperson Olga Sarrado Mur in an email to CPJ. The need is only growing: “UNHCR estimates that almost 3 million refugees will be in need of resettlement in 2025, including over 8,600 originating from Ethiopia,” Sarrado Mur said.

“Unfortunately, there are very limited resettlement places available worldwide, besides being a life-saving intervention for at-risk refugees,” said Sarrado Mur.

Without a stable source of income, Tesfa-Alem said he was living “in terrible conditions,” with months of overdue rent.

“Stress, lack of freedom of movement, and economic reasons: all these lead me to depression and even considering returning home to face the consequences,” he said, voicing a frustration shared by all of the journalists that spoke to CPJ about the complexities and delays they encountered navigating the asylum system.

‘No Ethiopian security services will knock on my door’

Most of the journalists who spoke to CPJ described great difficulties in returning to journalism. A lucky few have succeeded.

Yayesew Shimelis, founder of the YouTube channel Ethio Forum whose reporting was critical of the Ethiopian government, was arrested multiple times between 2019 and 2022.

In 2021, he was detained for 58 days, one of a dozen journalists and media workers held incommunicado at Awash Sebat, another remote military camp in Ethiopia’s Afar state. The following year, he was abducted by people who broke into his house, blindfolded him, and held him in an unknown location for 11 days.

“My only two options were living in my beloved country without working my beloved job; or leaving my beloved country and working my beloved job,” he told CPJ.

At Addis Ababa airport in 2023, he said he was interrogated for two hours about his destination and the purpose of his trip. He told officials he was attending a wedding and promised to be back in two weeks. When his flight took off, Yayesaw was overwhelmed with relief and sadness to be “suddenly losing my country.”

“I was crying, literally crying, when the plane took off,” he told CPJ. “People on the plane thought I was going to a funeral.”

In exile, Yayesew feels “free”. He continues to run Ethio Forum and even published a book about Prime Minister Abiy earlier this year.

“Now I am 100% sure that no Ethiopian security services will knock on my door the morning after I publish a critical report,” he said.

But for Belete, only three months on from his escape, such peace remains a distant dream.

He struggles to afford food and rent and worries who he can trust.

“When I left my country, although I was expecting challenges, I was not prepared for how tough it would be,” he told CPJ.

Belete says it’s difficult to report on Ethiopia from abroad and that sometimes he must choose between doing the work he loves and making a living.

“I find myself in a state of profound uncertainty about my future,” said Belete. “I am caught between the aspiration to pursue my journalism career and the necessity of leading an ordinary life to secure my livelihood”.

This content originally appeared on Committee to Protect Journalists and was authored by CPJ Africa Program Staff.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on The Progressive — A voice for peace, social justice, and the common good and was authored by Tessie Ragan.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.