In a year marked by tightened restrictions and unrest, Telegram sent a clear message to authoritarian governments who tried to keep it quiet in 2020. But as the app, which has earned a reputation as a free-speech platform, looks to spread the word in Iran and China, its popularity among messengers of violence and hate remains a concern.

Telegram has emerged as an essential tool for opposition movements in places like Belarus and Iran and won a huge victory when the Russian authorities gave up on their effort to ban the app after two fruitless years during which senior officials continued to use it themselves.

But protesters and open media are not the only ones who find sanctuary in a tool like Telegram. Terrorists, hate groups, and purveyors of gore also see the benefits of encrypted group chats that can reach large audiences without censorship.

Not Under Your Thumb

Nowhere was the hidden hand of Telegram more apparent in 2020 than in Belarus, where activists and opposition politicians relied on the platform to counter the authorities’ attempts to control the narrative in a crucial election year.

Ahead of the August 9 vote pitting authoritarian incumbent Alyaksandr Lukashenka against a thinned pool of opposition candidates, the Belarusian authorities did their best to intimidate administrators of rogue Telegram channels.

When three Telegram-based opposition bloggers were arrested in June, the rights watchdog Amnesty International decried the pressure against alternative sources of information.

A quick perusal of some of the more sordid open channels on Telegram reveals that it is a place for violence, criminal activity, and abusers, regardless of what Europol says.

“The Belarusian authorities are carrying out a full-scale purge of dissenting voices, using repressive laws to stifle criticism ahead of the elections,” said Aisha Jung, Amnesty International’s senior campaigner on Belarus.

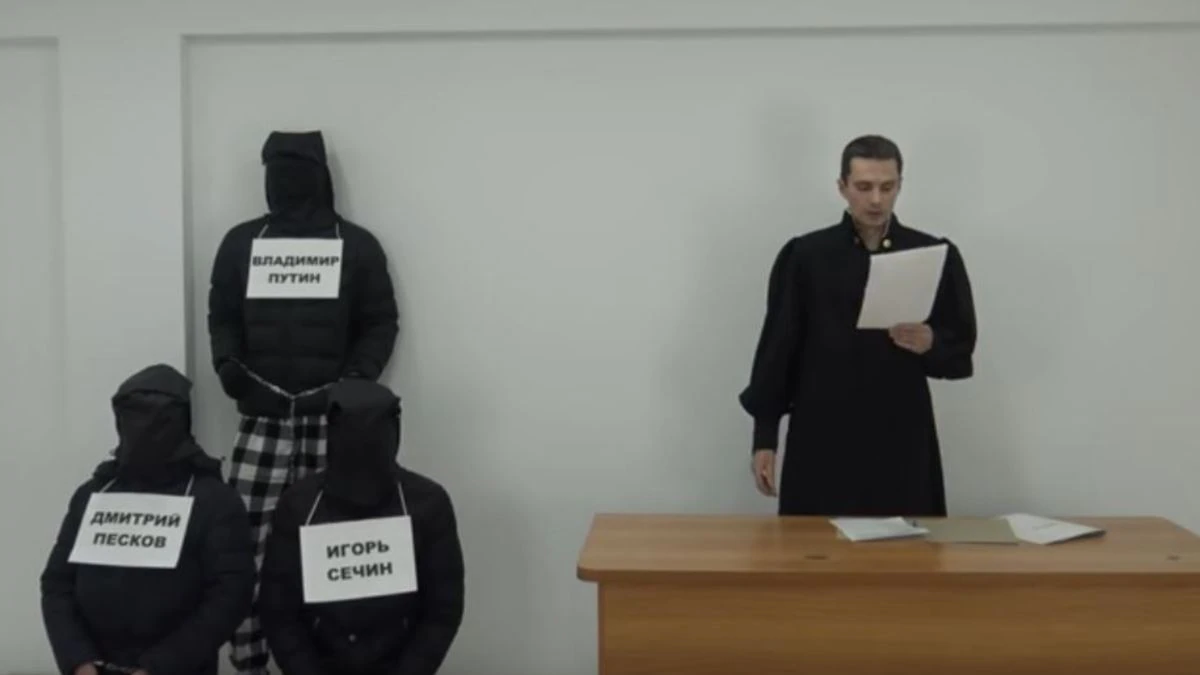

After Lukashenka claimed he had won a sixth straight term, triggering mass protests that continue to bring people onto the streets to contest the outcome, despite a violent police crackdown, it was the authorities who were crying foul.

“You see: a square was drawn in a well-known channel on Sunday — go there. They went. They stood in this square,” Lukashenka said after attempts to block the websites of independent outlets drove the opposition-minded to Telegram. “They drew another one — go there, and then go to the Palace of Independence. This is how they manage.”

In November, the state Investigative Committee was accusing the creators of the Poland-based Nexta channel on Telegram of organizing what it called “mass riots.” By the end of the month, the creators of the opposition-friendly news source had been added to the State Security Committee’s list of “persons involved in terrorist activities.”

Claiming that up to 15 percent of the citizens of Minsk were using Telegram and generating 50,000 to 100,000 messages a day to coordinate actions through 1,000 channels, the deputy head of the presidential administration said that “these are huge figures, and we have no right to turn a blind eye to this.”

But by then, even Lukashenka had long accepted the reality of Telegram’s power, using a newly created state Telegram channel to post videos in August of him brandishing an AK-47 and barking orders to security forces from his helicopter.

As the authoritarian leader told friendly members of the press in September: “How can you stop these Telegram channels? Can you block them? No. Nobody can.”

‘If You Can’t Beat ‘Em…’

Belarus was not the only one to grudgingly concede to Telegram this year. Russia too, after a two-year battle to ban the app, took the “if you can’t beat them, join them” approach.

“Roskomnadzor is dropping its demands to restrict access to Telegram messenger in agreement with Russia’s Prosecutor-General’s Office,” the country’s communications regulator announced in June.

Shortly afterward, the Communications Ministry admitted that it was “technically impossible” to block the messaging app.

The ban, introduced after Telegram refused to comply with Russian demands that it hand over encryption keys to help fight terrorism, never really stuck anyway.

Telegram founder Pavel Durov: “Over the course of the last two years, we had to regularly upgrade our ‘unblocking’ technology to stay ahead of the censors.”

Despite official efforts to block it, courts, political heavyweights, and even the Russian Foreign Ministry had continued to use the platform. And according to Telegram founder Pavel Durov, use of the app had doubled since the ban, with 30 percent of its 400 million active users coming from Russia.

The Russian entrepreneur had some experience defying the Kremlin, having created and headed the social-networking site VK before he was dismissed as CEO in 2014 after refusing orders to block Russian opposition leader Aleksei Navalny’s site and to hand over information about Maidan protesters in Ukraine.

After Telegram was unblocked, Durov explained that “over the course of the last two years, we had to regularly upgrade our ‘unblocking’ technology to stay ahead of the censors.”

The strategy included the formation of a “Digital Resistance” movement employing rotating proxy servers and other means of hiding traffic to circumvent censorship.

“To put it simply, the ban didn’t work,” Durov said.

Steps Taken, But Not Enough

There was some merit to Russia citing the effort to fight terrorism as a reason for introducing the ban in the first place, considering that its initial demand for encryption keys stemmed from attempts to decipher comments authorities said were made on Telegram by a suicide bomber who killed 15 people in St. Petersburg in 2017.

Going into 2020, Telegram was still dealing with such criticism, including that it was not doing enough to prevent extremist groups like Islamic State from disseminating information.

Among the steps taken by Telegram were the introduction of an ISIS Watch feature that publishes daily updates on banned terrorist content and encouraging users to report extremist content.

Europol even lauded Telegram’s actions, saying in late 2019 that “Telegram is no place for violence, criminal activity, and abusers. The company has put forth considerable effort to root out the abusers of the platform by both bolstering its technical capacity in countering malicious content and establishing close partnerships with international organizations such as Europol.”

Those efforts, as well as Telegram’s role as a public-service beacon during the coronavirus pandemic, appear to have factored into the lifting of the digital blockade.

But they didn’t end criticism that dangerous minds were still exploiting the app’s free-speech policies.

Within hours, the manifesto of a gunman who killed nine people near Frankfurt, Germany, in February was being spread by right-wing extremist groups on Telegram.

A racially motivated shooting in February that left nine people dead in a town outside Frankfurt, Germany, sparked renewed concerns. Within hours of the attack, the perpetrator’s manifesto was being spread by right-wing extremist groups on Telegram.

Scores of white nationalist groups, according to an analysis by Vice News, had made the switch to Telegram after they were kicked off mainstream social media like Facebook and Twitter.

“Telegram makes a lot of sense for those groups: The app allows users to upload unlimited videos, images, audio clips, and other files, and its founder has repeatedly affirmed his commitment to protecting user data from third parties — including governments,” Vice News wrote.

The Counter Extremism Project, an international policy organization formed to combat the growing threat from extremist ideologies, reported in May that it was still finding Islamic State propaganda on Telegram.

In addition, the project said it had found “multiple white supremacist and neo-Nazi groups” on Telegram celebrating the shooting death in the United States of an unarmed black man, as well as encouraging mass shootings and violence against African Americans.

What Did I Just Watch?

A quick perusal of some of the more sordid open channels on Telegram reveals that it is a place for violence, criminal activity, and abusers, regardless of what Europol says.

Multiple channels host full-length, uncensored videos showing the perpetrator of the 2019 Christchurch mosque shootings in New Zealand preparing for and carrying out the attacks in which 51 people were killed and 40 injured.

Multiple videos of school shootings are available, and uncut videos of ordinary people being stabbed, shot, bludgeoned, or mutilated are ubiquitous.

Compromising sex videos of Russian celebrities and politicians are there for the watching, as is a recent live-streamed incident in which a popular vlogger reportedly accepted money to lock his girlfriend outside in subzero temperatures, where she died.

Amid the recent fighting between Azerbaijan and Armenia over the breakaway territory of Nagorno-Karabakh, videos apparently taken by Azerbaijani soldiers and distributed on Telegram show executions, including beheadings, as well as other abuses of POWs. The videos prompted an investigation by the Council of Europe, Europe’s top human rights watchdog.

Ihar Losik is the administrator of the Telegram-based Belarus Of The Brain channel and a media consultant for RFE/RL.

Digital Resistance To Fight Another Day

Now, as 2021 begins, the fight over Telegram is continuing — and expanding.

In Belarus, the authorities continue to pursue charges against Telegram bloggers they accuse of fomenting unrest over the outcome of the August presidential vote. Among them is n mid-December, Losik announced that he had launched a hunger strike to protest his treatment and potential eight-year prison sentence.

In Iran, the execution of activist and journalist Ruhollah Zam has sparked international outrage. Zam, who headed AmadNews — which had been suspended by Telegram in 2018 for publishing information about Molotov cocktails but was revived under a different name — was credited with helping inspire anti-government protests in 2017.

And in China, where Telegram is banned, the app has seen a surge of millions of new users as other messaging platforms have suffered outages.

Both Iran and China have come into focus among free-speech advocates in recent years, including efforts to develop technologies such as Signal and Tor that allow people to access the Internet and communicate privately.

“We don’t want this technology to get rusty and obsolete. That is why we have decided to direct our anti-censorship resources into other places where Telegram is still banned by governments — places like Iran and China,” Durov wrote on his personal channel after Russia unblocked Telegram. “We ask the admins of the former proxy servers for Russian users to focus their efforts on these countries.”

“The Digital Resistance movement doesn’t end with last week’s cease-fire in Russia,” Durov wrote in June. “It is just getting started — and going global.”

This post was originally published on Radio Free.