Unbeknownst to much of the public, Big Tech exacts heavy tolls on public health, the environment, and democracy. The detrimental combination of an unregulated tech sector, pronounced rise in cyberattacks and data theft, and widespread digital and media illiteracy—as noted in my previous Dispatch on Big Data’s surveillance complex—is exacerbated by legacy media’s failure to inform the public of these risks. While establishment news outlets cover major security breaches in Big Tech’s troves of personal identifiable information (PII) and their costs to individuals, businesses, and national security, this coverage fails to address the negative impacts of Big Tech on the full health of our political system, civic engagement, and ecosystems.

Marietje Schaake, an AI Policy fellow at Stanford University’s Institute for Human-Centered AI Policy, argues that Big Tech’s unrestrained hand in all three branches of the government, the military, local and national elections, policing, workplace monitoring, and surveillance capitalism undermine American society in ways the public has failed to grasp. Indeed, little in the corporate press helps the public understand exactly how data centers—the facilities that process and store vast amounts of data—do more than endanger PII. Greenlit by the Trump administration, data centers accelerate ecosystem harms through their unmitigated appropriation of natural resources, including water, and the subsequent greenhouse gas emissions that increase ambient pollution and its attendant diseases.

Adding insult to the public’s right to be informed, corporate news rarely sheds light on how an ethical, independent press serves the public good and functions to balance power in a democracy. A 2023 civics poll by the University of Pennsylvania’s Annenberg School found that only a quarter of respondents knew that press freedom is a constitutional right and a counterbalance to the powers of government and capitalism. The gutting of local news in favor of commercial interests has only accelerated this knowledge blackout.

The demand for AI by corporatists, military AI venture capitalists, and consumers—and resultant demand for data centers—is outpacing utilities infrastructure, traditional power grid capabilities, and the renewable energy sector. Big Tech companies, such as Amazon and Meta, strain municipal water systems and regional power grids, reducing the capacity to operate all things residential and local. In Newton County, Georgia, for example, Meta’s $750 million data center, which sucks up approximately 500,000 gallons of water a day, has contaminated local groundwater and caused taps in nearby homes to run dry. What’s more, the AI boom comes at a time when hot wars are flaring and global temperatures are soaring faster than scientists once predicted.

Constant connectivity, algorithms, and AI-generated content delude individual internet and device users into believing that they’re well informed. However, the decline of civics awareness in the United States—compounded by rampant digital and media illiteracy, ubiquitous state and corporate surveillance, and lax news reporting—makes for an easily manipulated citizenry, asserts attorney and privacy expert, Heidi Boghosian. This is especially disconcerting given the creeping spread of authoritarianism, smackdown on civil liberties, and surging demand for AI everything.

Open [but not transparent] AI

While the companies that develop and deploy popular AI-powered tools lionize the wonders of their products and services, they keep hidden the unsustainable impacts on our world. To borrow from Cory Doctorow, the “enshittification” of the online economy traps consumers, vendors, and advertisers in “the organizing principle of US statecraft,” as well as by more mundane capitalist surveillance. Without government oversight or a Fourth Estate to compel these tech corporations to reveal their shadow side, much of the public is not only in the dark but in harm’s way.

At the most basic level, consumers should know that OpenAI, the company that owns ChatGPT, collects private data and chat inputs, regardless of whether users are logged in or not. Any time users visit or interact with ChatGPT, their log data (the Internet Protocol address, browser type and settings, date and time of the site visit, and interaction with the service), usage data (time zone, country, and type of device used), device details (device name and identifiers, operating system, and browser used), location information from the device’s GPS, and cookies, which store the user’s personal information, are saved. Most users have no idea that they can opt out.

OpenAI claims it saves data only for “fine-tuning,” a process of enhancing the performance and capabilities of AI models, and for human review “to identify biases or harmful outputs.” OpenAI also claims not to use data for marketing and advertising purposes or to sell information to third parties without prior consent. Most users, however, are as oblivious to the means of consent as to the means of opting out. This is by design.

In July, the US Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit vacated the Federal Trade Commission’s “click-to-cancel” rule, which would have made online unsubscribing easier. The ruling would have covered all forms of negative option marketing—programs that give sellers free rein to interpret customer inaction as “opting in,” consenting to subscriptions and unwittingly accruing charges. Director of litigation at the Electronic Privacy Information Center, John Davisson, commented that the court’s decision was poorly reasoned, and only those with financial or career advancement motives would argue in favor of subscription traps.

Even if OpenAI is actually protective of the private data it stores, it is not above disclosing user data to affiliates, law enforcement, and the government. Moreover, ChatGPT practices are noncompliant with the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), the global gold standard of data privacy protection. Although OpenAI says it strips PII and anonymizes data, its practice of “indefinite retention” does not comply with the GDPR’s stipulation for data storage limitations, nor does OpenAI sufficiently guarantee irreversible data de-identification.

As science and tech reporter Will Knight wrote for Wired, “Once data is baked into an AI model today, extracting it from that model is a bit like trying to recover the eggs from a finished cake.” Whenever a tech company collects and keeps PII, there are security risks. The more data captured and stored by a company, the more likely it will be exposed to a system bug, hack, or breach, such as the ChatGPT breach in March 2023.

OpenAI has said it will comply with the EU’s AI Code of Practice for General-Purpose AI, which aims to foster transparency, information sharing, and best practices for model and risk assessment among tech companies. Microsoft has said that it will likely sign on to compliance, too; while Meta, on the other hand, flatly refuses to comply, much like it refuses to abide by environmental regulations.

To no one’s surprise, the EU code has already become politicized, and the White House has issued its own AI Action Plan to “remove red tape.” The plan also purports to remove “woke Marxist lunacy in the AI models,” eliminating such topics as diversity, equity, and inclusion and climate change. As Trump crusades against regulation and “bias,” the White House-allied Meta decries political concerns over compliance with the EU’s AI code. Meta’s claim is coincidental; British Courts, based on the United Kingdom’s GDPR obligations, ruled that anyone in a country covered by the GDPR has the right to request Meta to stop using their personal data for targeted advertising.

Big Tech’s open secrets

Information on the tech industry’s environmental and health impacts exists, attests artificial intelligence researcher Sasha Luccioni. The public is simply not being informed. This lack of transparency, warns Luccioni, portends significant environmental and health consequences. Too often, industry opaqueness is excused by insiders as “competition” to which they feel entitled, or blamed on the broad scope of artificial intelligence products and services—smart devices, recommender systems, internet searches, autonomous vehicles, machine learning, the list goes on. Allegedly, there’s too much variety to reasonably quantify consequences.

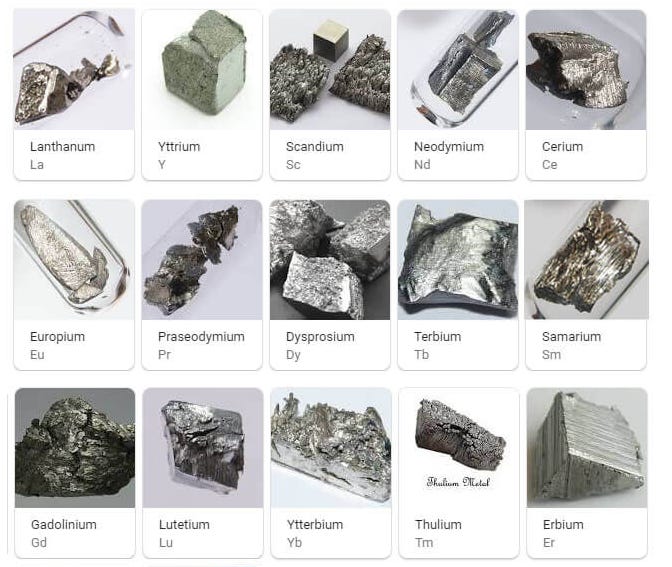

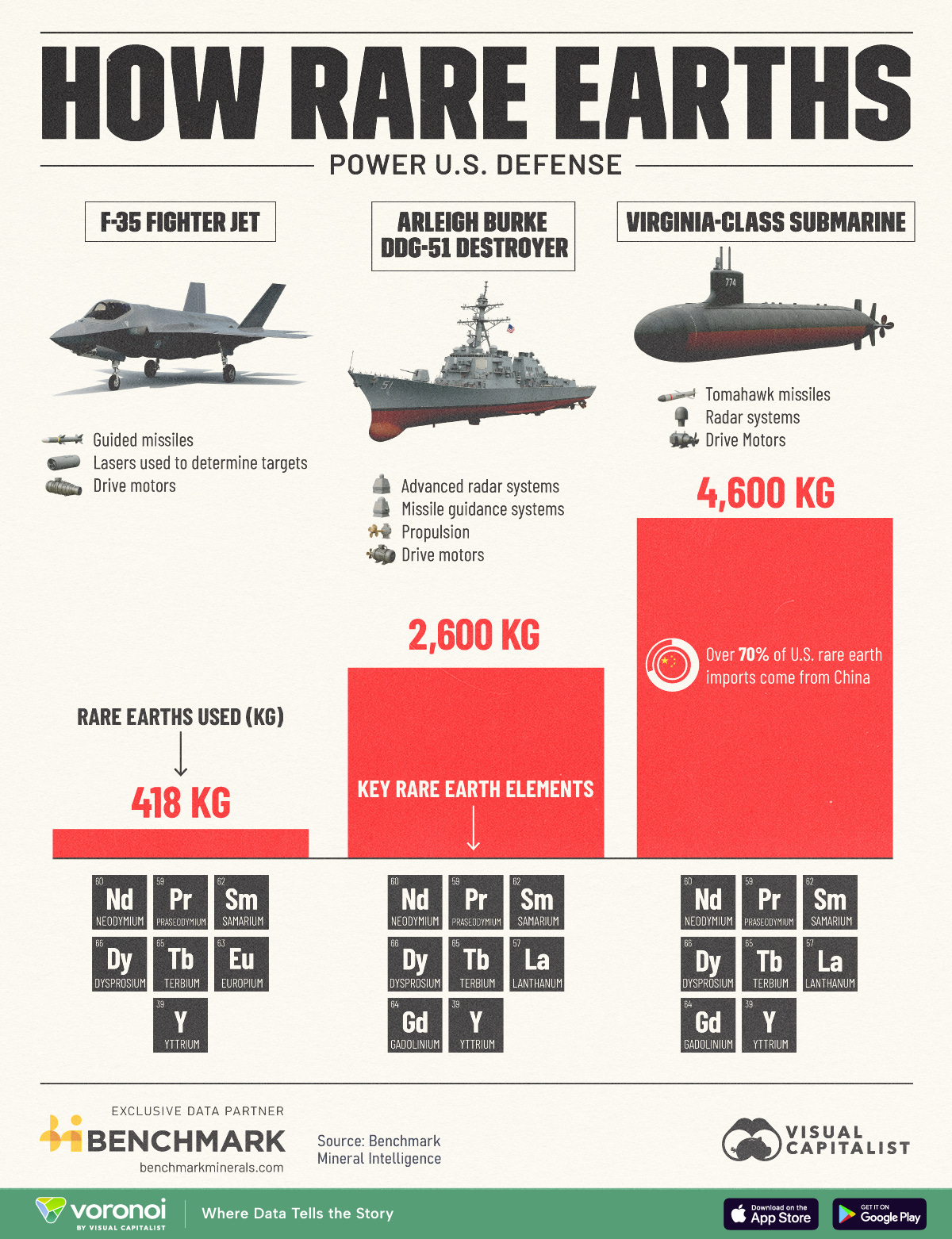

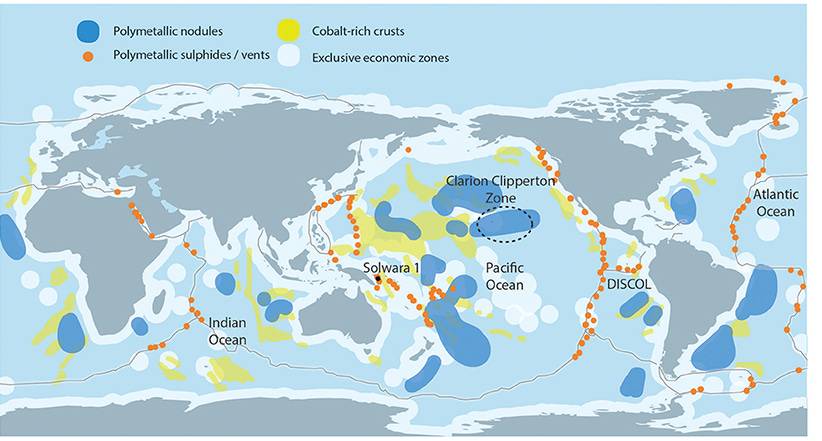

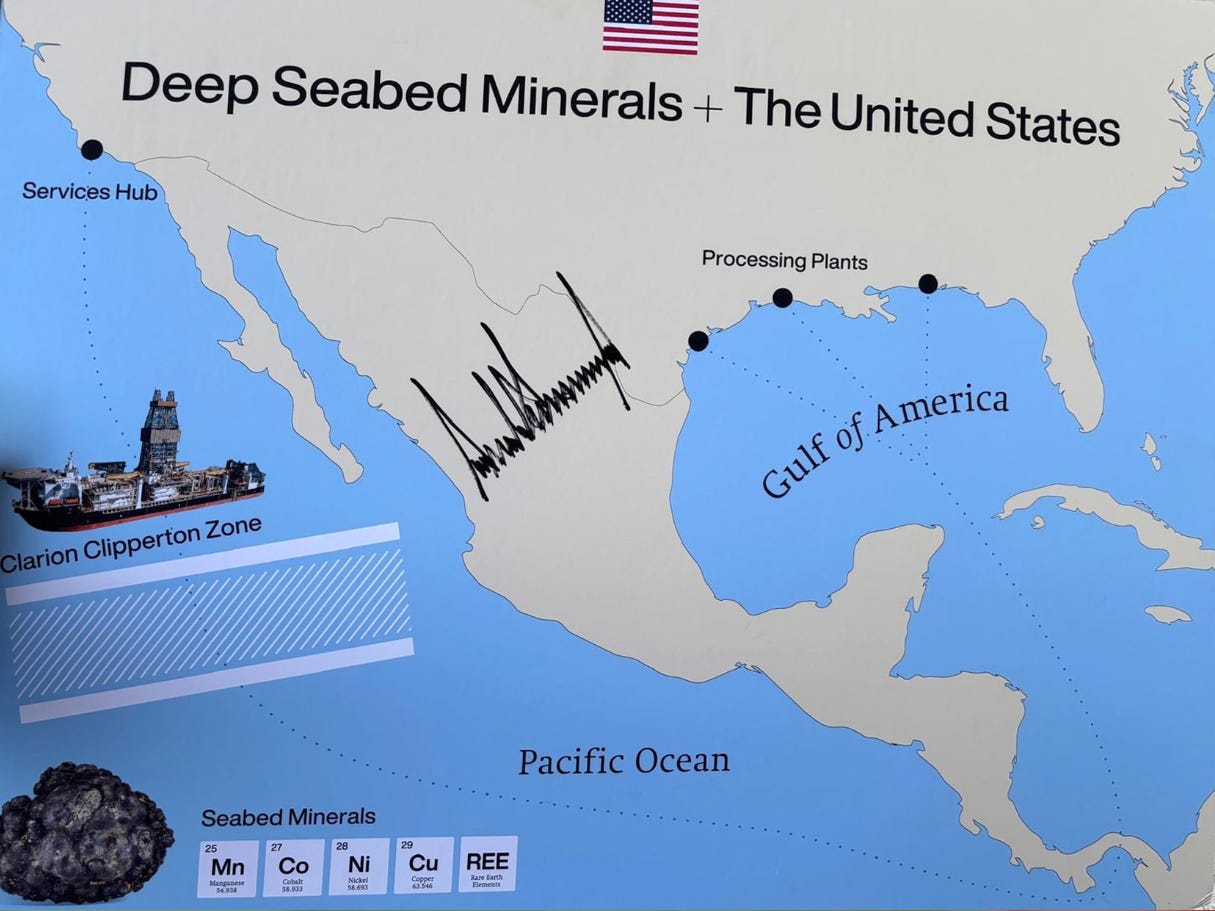

Those consequences are quantifiable, though. While numbers vary and are on the ascent, there are at least 3,900 data centers in the United States and 10,000 worldwide. An average data center houses complex networking equipment, servers, and systems for cooling systems, lighting, security, and storage, all requiring copious rare earth minerals, water, and electricity to operate.

The densest data center area exists in Northern Virginia, just outside the nation’s capital. “Data Center Alley,” also known as the “Data Center Capital of the World,” has the highest concentration of data centers not only in the United States but in the entire world, consuming millions of gallons of water every day. International hydrologist Newsha Ajami has documented how water shortages around the world are being worsened by Big Data. For tech companies, “water is an afterthought.”

Powered by fossil fuels, these data centers pose serious public health implications. According to research in 2024, training one large language model (LLM) with 213 million parameters produced 626,155 pounds of CO2 emissions, “equivalent to the lifetime emissions of five cars, including fuel.” Stated another way, such AI training “can produce air pollutants equivalent to more than 10,000 round trips by car between Los Angeles and New York City.”

Reasoning models generate more “thinking tokens” and use as much as 50 percent more energy than other AI models. Google and Microsoft search features purportedly use smaller models when possible, which, theoretically, can provide quick responses with less energy. It’s unclear when or if smaller models are actually invoked, and the bottom line, explained climate reporter Molly Taft, is that model providers are not informing consumers that speedier AI response times almost always equate to higher energy usage.

Profits over people

AI is rapidly becoming a public utility, profoundly shaping society, surmise Caltech’s Adam Wierman and Shaolei Ren of the University of California, Riverside. In the last few years, AI has outgrown its niche in the tech sector to become integral to digital economies, government, and security. AI has merged more closely with daily life, replacing human jobs and decision-making, and has thus created a reliance on services currently controlled by private corporations. Because other essential services such as water, electricity, and communications are treated as public utilities, there’s growing discussion about whether AI should be regulated under a similar public utility model.

That said, data centers need power grids, most of which depend on fossil fuel-generated electricity that stresses national and global energy stores. Data centers also need backup generators for brownout and blackout periods. With limited clean, reliable backup options, despite the known environmental and health consequences of burning diesel, diesel generators remain the industry’s go-to.

Whether the public realizes it or not, the environment and citizens are being polluted by the actions of private tech firms. Outputs from data centers inject dangerous fine particulate matter and nitrogen oxides (NOx) into the air, immediately worsening cardiovascular conditions, asthma, cancer, and even cognitive decline, caution Wierman and Ren. Contrary to popular belief, air pollutants are not localized to their emission sources. And, although chemically different, carbon (CO2) is not contained by location either.

Of great concern is that in “World Data Capital Virginia,” data centers are incentivized with tax breaks. Worse still, the (misleadingly named) Environmental Protection Agency plans to remove all limits on greenhouse gas emissions from power plants, according to documents obtained by the New York Times. Thus, treating AI and data centers as public utilities presents a double-edged sword. Can a government that slashes regulations to provide more profit to industry while destroying its citizens’ health along with the natural world be trusted to fairly price and equitably distribute access to all? Would said government suddenly start protecting citizens’ privacy and sensitive data?

The larger question, perhaps, asks if the US is truly a democracy. Or is it a technogarchy, or an AI-tocracy? The 2024 AI Global Surveillance (AIGS) Index ranked the United States first for its deployment of advanced AI surveillance tools that “monitor, track, and surveil citizens to accomplish a range of objectives— some lawful, others that violate human rights, and many of which fall into a murky middle ground,” the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace reported.

Surveillance has long been the purview of authoritarian regimes, but in so-called democracies such as the United States, the scale and intensity of AI use is leveraged both globally through military operations and domestically to target and surveil civilians. In cities such as Scarsdale, New York, and Norfolk, Virginia, citizens are beginning to speak out against the systems that are “immensely popular with politicians and law enforcement, even though they do real and palpable damage to the citizenry.”

Furthermore, tracking civilians to “deter civil disobedience” has never been easier, evidenced in June by the rapid mobilization of boots on the ground amid the peaceful protests of ICE raids in Los Angeles. AI-powered surveillance acts as the government’s “digital scarecrow,” chilling the American tradition and First Amendment right to protest and the Fourth Estate’s right to report.

The public is only just starting to become aware of algorithmic biases in AI training datasets and their prejudicial impact on predictive policing, or profiling, algorithms, and other analytic tools used by law enforcement. City street lights and traffic light cameras, facial recognition systems, video monitoring in and around business and government buildings, as well as smart speakers, smart toys, keyless entry locks, automobile intelligent dash displays, and insurance antitheft tracking systems are all embedded with algorithmic biases.

Checking Big Tech’s unchecked power

Given the level and surreptitiousness of surveillance, the media are doubly tasked with treading carefully to avoid being targeted and accurately informing the public’s perception of data collection and data centers. Reporting that glorifies techbros and AI is unscrupulous and antithetical to democracy: In an era where billionaire techbros and wanna-be-kings are wielding every available apparatus of government and capitalism to gatekeep information, the public needs an ethical press committed to seeking truth, reporting it, and critically covering how AI is shifting power.

If people comprehend what’s at stake—their personal privacy and health, the environment, and democracy itself—they may be more inclined to make different decisions about their AI engagement and media consumption. An independent press that prioritizes public enlightenment means that citizens and consumers still have choices, starting with basic data privacy self-controls that resist AI surveillance and stand up for democratic self-governance.

Just as a healthy environment, replete with clean air and water, has been declared a human right by the United Nations, privacy is enshrined in Article 12 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Although human rights are subject to national laws, water, air, and the internet know no national borders. It is, therefore, incumbent upon communities and the press to uphold these rights and to hold power to account.

This spring, residents of Pittsylvania County, Virginia, did just that. Thanks to independent journalism and civic participation, residents pushed back against the corporate advertising meant to convince the county that the fossil fuels powering the region’s data centers are “clean.” Propagandistic campaigns were similarly applied in Memphis, Tennessee, where proponents of Elon Musk’s data center—which has the footprint of thirteen football fields—circulated fliers to residents of nearby, historically Black neighborhoods, proclaiming the super-polluting xAI has low emissions. “Colossus,” Musk’s name for what’s slated to be the world’s biggest supercomputer, powers xAI’s Hitler-loving chatbot Grok.

The Southern Environmental Law Center exposed with satellite and thermal imagery how xAI, which neglected to obtain legally required air permits, brought in at least 35 portable methane gas turbines to help power Colossus. Tennessee reporter Ren Brabenec said that Memphis has become a sacrifice zone and expects the communities there to push back.

Meanwhile, in Pittsylvania, Virginia, residents succeeded in halting the proposed expansion of data centers that would damage the region’s environment and public health. Elizabeth Putfark, attorney with the Southern Environmental Law Center, affirmed that communities, including local journalists, are a formidable force when acting in solidarity for the public welfare.

Best practices

Because AI surveillance is a threat to democracies everywhere, we must each take measures to counter “government use of AI for social control,” contends Abi Olvera, senior fellow with the Council on Strategic Risks. Harlo Holmes, director of digital security at the Freedom of the Press Foundation, told Wired that consumers must make technology choices under the premise that they’re our “last line of defense.” Steps to building that last line of defense include digital and media literacies and digital hygiene, and at least a cursory understanding of how data is stored and its far-reaching impacts.

Best defensive practices employed by media professionals can also serve as best practices for individuals. This means becoming familiar with laws and regulations, taking every precaution to protect personal information on the internet and during online communications, and engaging in responsible civic discourse. A free and democratic society is only as strong as its citizens’ abilities to make informed decisions, which, in turn, are only as strong as their media and digital literacy skills and the quality of information they consume.

This essay first published here: https://www.projectcensored.org/hidden-costs-big-data-surveillance-complex/

The post

The Hidden Costs of the Big Data Surveillance Complex first appeared on

Dissident Voice.

This post was originally published on Dissident Voice.