The British home secretary, Priti Patel, will decide this month whether Julian Assange is to be extradited to the United States, where he faces a sentence of up to 175 years – served most likely in strict, 24-hour isolation in a US super-max jail.

The British home secretary, Priti Patel, will decide this month whether Julian Assange is to be extradited to the United States, where he faces a sentence of up to 175 years – served most likely in strict, 24-hour isolation in a US super-max jail.

He has already spent three years in similarly harsh conditions in London’s high-security Belmarsh prison.

The 18 charges laid against Assange in the US relate to the publication by WikiLeaks in 2010 of leaked official documents, many of them showing that the US and UK were responsible for war crimes in Iraq and Afghanistan. No one has been brought to justice for those crimes.

Instead, the US has defined Assange’s journalism as espionage – and by implication asserted a right to seize any journalist in the world who takes on the US national security state – and in a series of extradition hearings, the British courts have given their blessing.

The lengthy proceedings against Assange have been carried out in courtrooms with tightly restricted access and in circumstances that have repeatedly denied journalists the ability to cover the case properly.

Despite the grave implications for a free press and democratic accountability, however, Assange’s plight has provoked little more than a flicker of concern from much of the western media.

Few observers appear to be in any doubt that Patel will sign off on the US extradition order – least of all Nils Melzer, a law professor, and a United Nations’ special rapporteur.

In his role as the UN’s expert on torture, Melzer has made it his job since 2019 to scrutinise not only Assange’s treatment during his 12 years of increasing confinement – overseen by the UK courts – but also the extent to which due process and the rule of law have been followed in pursuing the WikiLeaks founder.

Melzer has distilled his detailed research into a new book, The Trial of Julian Assange, that provides a shocking account of rampant lawlessness by the main states involved – Britain, Sweden, the US, and Ecuador. It also documents a sophisticated campaign of misinformation and character assassination to obscure those misdeeds.

The result, Melzer concludes, has been a relentless assault not only on Assange’s fundamental rights but his physical, mental, and emotional wellbeing that Melzer classifies as psychological torture.

The UN rapporteur argues that the UK has invested far too much money and muscle in securing Assange’s prosecution on behalf of the US, and has too pressing a need itself to deter others from following Assange’s path in exposing western crimes, to risk letting Assange walk free.

It has instead participated in a wide-ranging legal charade to obscure the political nature of Assange’s incarceration. And in doing so, it has systematically ridden roughshod over the rule of law.

Melzer believes Assange’s case is so important because it sets a precedent to erode the most basic liberties the rest of us take for granted. He opens the book with a quote from Otto Gritschneder, a German lawyer who observed up close the rise of the Nazis, “those who sleep in a democracy will wake up in a dictatorship”.

Back to the wall

Melzer has raised his voice because he believes that in the Assange case any residual institutional checks and balances on state power, especially those of the US, have been subdued.

He points out that even the prominent human rights group Amnesty International has avoided characterising Assange as a “prisoner of conscience”, despite his meeting all the criteria, with the group apparently fearful of a backlash from funders (p. 81).

He notes too that, aside from the UN’s Working Group on Arbitrary Detention, comprising expert law professors, the UN itself has largely ignored the abuses of Assange’s rights (p. 3). In large part, that is because even states like Russia and China are reluctant to turn Assange’s political persecution into a stick with which to beat the West – as might otherwise have been expected.

The reason, Melzer observes, is that WikiLeaks’ model of journalism demands greater accountability and transparency from all states. With Ecuador’s belated abandonment of Assange, he appears to be utterly at the mercy of the world’s main superpower.

Instead, Melzer argues, Britain and the US have cleared the way to vilify Assange and incrementally disappear him under the pretense of a series of legal proceedings. That has been made possible only because of complicity from prosecutors and the judiciary, who are pursuing the path of least resistance in silencing Assange and the cause he represents.

It is what Melzer terms an official “policy of small compromises” – with dramatic consequences (pp. 250-1).

His 330-page book is so packed with examples of abuses of due process – at the legal, prosecutorial, and judicial levels – that it is impossible to summarise even a tiny fraction of them.

However, the UN rapporteur refuses to label this as a conspiracy – if only because to do so would be to indict himself as part of it. He admits that when Assange’s lawyers first contacted him for help in 2018, arguing that the conditions of Assange’s incarceration amounted to torture, he ignored their pleas.

As he now recognises, he too had been influenced by the demonisation of Assange, despite his long professional and academic training to recognise techniques of perception management and political persecution.

“To me, like most people around the world, he was just a rapist, hacker, spy, and narcissist,” he says (p. 10).

It was only later when Melzer finally agreed to examine the effects of Assange’s long-term confinement on his health – and found the British authorities obstructing his investigation at every turn and openly deceiving him – that he probed deeper. When he started to pick at the legal narratives around Assange, the threads quickly unravelled.

He points to the risks of speaking up – a price he has experienced firsthand – that have kept others silent.

“With my uncompromising stance, I put not only my credibility at risk, but also my career and, potentially, even my personal safety… Now, I suddenly found myself with my back to the wall, defending human rights and the rule of law against the very democracies which I had always considered to be my closest allies in the fight against torture. It was a steep and painful learning curve” (p. 97).

He adds regretfully: “I had inadvertently become a dissident within the system itself” (p. 269).

Subversion of law

The web of complex cases that have ensnared the WikiLeaks founder – and kept him incarcerated – have included an entirely unproductive, decade-long sexual assault investigation by Sweden; an extended detention over a bail infraction that occurred after Assange was granted asylum by Ecuador from political extradition to the US; and the secret convening of a grand jury in the US, followed by endless hearings and appeals in the UK to extradite him as part of the very political persecution he warned of.

The goal throughout, says Melzer, has not been to expedite Assange’s prosecution – that would have risked exposing the absence of evidence against him in both the Swedish and US cases. Rather it has been to trap Assange in an interminable process of non-prosecution while he is imprisoned in ever-more draconian conditions and the public turned against him.

What appeared – at least to onlookers – to be the upholding of the law in Sweden, Britain and the US was the exact reverse: its repeated subversion. The failure to follow basic legal procedures was so consistent, argues Melzer, that it cannot be viewed as simply a series of unfortunate mistakes.

It aims at the “systematic persecution, silencing and destruction of an inconvenient political dissident” (p. 93).

Assange, in Melzer’s view, is not just a political prisoner. He is one whose life is being put in severe danger from relentless abuses that accord with the definition of psychological torture.

Such torture depends on its victim being intimidated, isolated, humiliated, and subjected to arbitrary decisions (p. 74). Melzer clarifies that the consequences of such torture not only break down the mental and emotional coping mechanisms of victims but over time have very tangible physical consequences too.

Melzer explains the so-called “Mandela Rules” – named after the long-jailed black resistance leader Nelson Mandela, who helped bring down South African apartheid – that limit the use of extreme forms of solitary confinement.

In Assange’s case, however, “this form of ill-treatment very quickly became the status quo” in Belmarsh, even though Assange was a “non-violent inmate posing no threat to anyone”. As his health deteriorated, prison authorities isolated him further, professedly for his own safety. As a result, Melzer concludes, Assange’s “silencing and abuse could be perpetuated indefinitely, all under the guise of concern for his health” (pp. 88-9).

The rapporteur observes that he would not be fulfilling his UN mandate if he failed to protest not only Assange’s torture but the fact that he is being tortured to protect those who committed torture and other war crimes exposed in the Iraq and Afghanistan logs published by WikiLeaks. They continue to escape justice with the active connivance of the same state authorities seeking to destroy Assange (p. 95).

With his long experience of handling torture cases around the world, Melzer suggests that Assange has great reserves of inner strength that have kept him alive, if increasingly frail and physically ill. Assange has lost a great deal of weight, is regularly confused and disorientated, and has suffered a minor stroke in Belmarsh.

Many of the rest of us, the reader is left to infer, might well have succumbed by now to a lethal heart attack or stroke, or have committed suicide.

A further troubling implication hangs over the book: that this is the ultimate ambition of those persecuting him. The current extradition hearings can be spun out indefinitely, with appeals right up to the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg, keeping Assange out of view all that time, further damaging his health, and providing a stronger deterrent effect on whistleblowers and other journalists.

This is a win-win, notes Melzer. If Assange’s mental health breaks down entirely, he can be locked away in a psychiatric institution. And if he dies, that would finally solve the inconvenience of sustaining the legal charade that has been needed to keep him silenced and out of view for so long (p. 322).

Sweden’s charade

Melzer spends much of the book reconstructing the 2010 accusations of sexual assault against Assange in Sweden. He does this not to discredit the two women involved – in fact, he argues that the Swedish legal system failed them as much as it did Assange – but because that case set the stage for the campaign to paint Assange as a rapist, narcissist, and fugitive from justice.

The US might never have been able to launch its overtly political persecution of Assange had he not already been turned into a popular hate figure over the Sweden case. His demonisation was needed – as well as his disappearance from view – to smooth the path to redefining national security journalism as espionage.

Melzer’s meticulous examination of the case – assisted by his fluency in Swedish – reveals something that the mainstream media coverage has ignored: Swedish prosecutors never had the semblance of a case against Assange, and apparently never the slightest intention to move the investigation beyond the initial taking of witness statements.

Nonetheless, as Melzer observes, it became “the longest ‘preliminary investigation’ in Swedish history” (p. 103).

The first prosecutor to examine the case, in 2010, immediately dropped the investigation, saying, “there is no suspicion of a crime” (p. 133).

When the case was finally wrapped up in 2019, many months before the statute of limitations was reached, a third prosecutor observed simply that “it cannot be assumed that further inquiries will change the evidential situation in any significant manner” (p. 261).

Couched in lawyerly language, that was an admission that interviewing Assange would not lead to any charges. The preceding nine years had been a legal charade.

But in those intervening years, the illusion of a credible case was so well sustained that major newspapers, including Britain’s The Guardian newspaper, repeatedly referred to “rape charges” against Assange, even though he had never been charged with anything.

More significantly, as Melzer keeps pointing out, the allegations against Assange were so clearly unsustainable that the Swedish authorities never sought to seriously investigate them. To do so would have instantly exposed their futility.

Instead, Assange was trapped. For the seven years that he was given asylum in Ecuador’s London embassy, Swedish prosecutors refused to follow normal procedures and interview him where he was, in person or via computer, to resolve the case. But the same prosecutors also refused to issue standard reassurances that he would not be extradited onwards to the US, which would have made his asylum in the embassy unnecessary.

In this way, Melzer argues “the rape suspect narrative could be perpetuated indefinitely without ever coming before a court. Publicly, this deliberately manufactured outcome could conveniently be blamed on Assange, by accusing him of having evaded justice” (p. 254).

Neutrality dropped

Ultimately, the success of the Swedish case in vilifying Assange derived from the fact that it was driven by a narrative almost impossible to question without appearing to belittle the two women at its centre.

But the rape narrative was not the women’s. It was effectively imposed on the case – and on them – by elements within the Swedish establishment, echoed by the Swedish media. Melzer hazards a guess as to why the chance to discredit Assange was seized on so aggressively.

After the fall of the Soviet Union, Swedish leaders dropped the country’s historic position of neutrality and threw their hand in with the US and the global “war on terror”. Stockholm was quickly integrated into the western security and intelligence community (p. 102).

All of that was put in jeopardy as Assange began eyeing Sweden as a new base for WikiLeaks, attracted by its constitutional protections for publishers.

In fact, he was in Sweden for precisely that reason in the run-up to WikiLeaks’ publication of the Iraq and Afghanistan war logs. It must have been only too obvious to the Swedish establishment that any move to headquarter WikiLeaks there risked setting Stockholm on a collision course with Washington (p. 159).

This, Melzer argues, is the context that helps to explain an astonishingly hasty decision by the police to notify the public prosecutor of a rape investigation against Assange minutes after a woman referred to only as “S” first spoke to a police officer in a central Stockholm station.

In fact, S and another woman, “A”, had not intended to make any allegation against Assange. After learning he had had sex with them in quick succession, they wanted him to take an HIV test. They thought approaching the police would force his hand (p. 115). The police had other ideas.

The irregularities in the handling of the case are so numerous, Melzer spends the best part of 100 pages documenting them. The women’s testimonies were not recorded, transcribed verbatim, or witnessed by a second officer. They were summarised.

The same, deeply flawed procedure – one that made it impossible to tell whether leading questions influenced their testimony or whether significant information was excluded – was employed during the interviews of witnesses friendly to the women. Assange’s interview and those of his allies, by contrast, were recorded and transcribed verbatim (p. 132).

The reason for the women making their statements – the desire to get an HIV test from Assange – was not mentioned in the police summaries.

In the case of S, her testimony was later altered without her knowledge, in highly dubious circumstances that have never been explained (pp. 139-41). The original text is redacted so it is impossible to know what was altered.

Stranger still, a criminal report of rape was logged against Assange on the police computer system at 4.11pm, 11 minutes after the initial meeting with S and 10 minutes before a senior officer had begun interviewing S – and two and half hours before that interview would finish (pp. 119-20).

In another sign of the astounding speed of developments, Sweden’s public prosecutor had received two criminal reports against Assange from the police by 5pm, long before the interview with S had been completed. The prosecutor then immediately issued an arrest warrant against Assange before the police summary was written and without taking into account that S did not agree to sign it (p. 121).

Almost immediately, the information was leaked to the Swedish media, and within an hour of receiving the criminal reports the public prosecutor had broken protocol by confirming the details to the Swedish media (p. 126).

Secret amendments

The constant lack of transparency in the treatment of Assange by Swedish, British, US, and Ecuadorian authorities becomes a theme in Melzer’s book. Evidence is not made available under freedom of information laws, or, if it is, it is heavily redacted or only some parts are released – presumably those that do not risk undermining the official narrative.

For four years, Assange’s lawyers were denied any copies of the text messages the two Swedish women sent – on the grounds they were “classified”. The messages were also denied to the Swedish courts, even when they were deliberating on whether to extend an arrest warrant for Assange (p. 124).

It was not until nine years later those messages were made public, though Melzer notes that the index numbers show many continue to be withheld. Most notably, 12 messages sent by S from the police station – when she is known to have been unhappy at the police narrative being imposed on her – are missing. They would likely have been crucial to Assange’s defence (p. 125).

Similarly, much of the later correspondence between British and Swedish prosecutors that kept Assange trapped in the Ecuadorian embassy for years was destroyed – even while the Swedish preliminary investigation was supposedly still being pursued (p. 106).

The text messages from the women that have been released, however, suggest strongly that they felt they were being railroaded into a version of events they had not agreed to.

Slowly they relented, the texts suggest, as the juggernaut of the official narrative bore down on them, with the implied threat that if they disputed it they risked prosecution themselves for providing false testimony (p. 130).

Moments after S entered the police station, she texted a friend to say that “the police officer appears to like the idea of getting him [Assange]” (p. 117).

In a later message, she writes that it was “the police who made up the charges” (p. 129). And when the state assigns her a high-profile lawyer, she observes only that she hopes he will get her “out of this shit” (p. 136).

In a further text, she says: “I didn’t want to be part of it [the case against Assange], but now I have no choice” (p. 137).

It was on the basis of the secret amendments made to S’s testimony by the police that the first prosecutor’s decision to drop the case against Assange was overturned, and the investigation reopened (p. 141). As Melzer notes, the faint hope of launching a prosecution of Assange essentially rested on one word: whether S was “asleep”, “half-asleep” or “sleepy” when they had sex.

Melzer write that “as long as the Swedish authorities are allowed to hide behind the convenient veil of secrecy, the truth about this dubious episode may never come to light” (p. 141).

No ordinary extradition’

These and many, many other glaring irregularities in the Swedish preliminary investigation documented by Melzer are vital to decoding what comes next. Or as Melzer concludes “the authorities were not pursuing justice in this case but a completely different, purely political agenda” (p. 147).

With the investigation hanging over his head, Assange struggled to build on the momentum of the Iraq and Afghanistan logs revealing systematic war crimes committed by the US and UK.

“The involved governments had successfully snatched the spotlight directed at them by WikiLeaks, turned it around, and pointed it at Assange,” Melzer observes.

They have been doing the same ever since.

Assange was given permission to leave Sweden after the new prosecutor assigned to the case repeatedly declined to interview him a second time (pp. 153-4).

But as soon as Assange departed for London, an Interpol Red Notice was issued, another extraordinary development given its use for serious international crimes, setting the stage for the fugitive-from-justice narrative (p. 167).

A European Arrest Warrant was approved by the UK courts soon afterwards – but, again exceptionally, after the judges had reversed the express will of the British parliament that such warrants could only be issued by a “judicial authority” in the country seeking extradition not the police or a prosecutor (pp. 177- 9).

A law was passed shortly after the ruling to close that loophole and make sure no one else would suffer Assange’s fate (p. 180).

As the noose tightened around the neck not only of Assange but WikiLeaks too – the group was denied server capacity, its bank accounts were blocked, credit companies refused to process payments (p. 172) – Assange had little choice but to accept that the US was the moving force behind the scenes.

He hurried into the Ecuadorean embassy after being offered political asylum. A new chapter of the same story was about to begin.

British officials in the Crown Prosecution Service, as the few surviving emails show, were the ones bullying their Swedish counterparts to keep going with the case as Swedish interest flagged. The UK, supposedly a disinterested party, insisted behind the scenes that Assange must be required to leave the embassy – and his asylum – to be interviewed in Stockholm (p. 174).

A CPS lawyer told Swedish counterparts “don’t you dare get cold feet!” (p. 186).

As Christmas neared, the Swedish prosecutor joked about Assange being a present, “I am OK without… In fact, it would be a shock to get that one!” (p. 187).

When she discussed with the CPS Swedish doubts about continuing the case, she apologised for “ruining your weekend” (p. 188).

In yet another email, a British CPS lawyer advised “please do not think that the case is being dealt with as just another extradition request” (p. 176).

Embassy spying operation

That may explain why William Hague, the UK’s foreign secretary at the time, risked a major diplomatic incident by threatening to violate Ecuadorean sovereignty and invade the embassy to arrest Assange (p. 184).

And why Sir Alan Duncan, a UK government minister, made regular entries in his diary, later published as a book, on how he was working aggressively behind the scenes to get Assange out of the embassy (pp. 200, 209, 273, 313).

And why the British police were ready to spend £16 million of public money besieging the embassy for seven years to enforce an extradition Swedish prosecutors seemed entirely uninterested in advancing (p. 188).

Ecuador, the only country ready to offer Assange sanctuary, rapidly changed course once its popular left-wing president Rafael Correa stepped down in 2017. His successor, Lenin Moreno, came under enormous diplomatic pressure from Washington and was offered significant financial incentives to give up Assange (p. 212).

At first, this appears to have chiefly involved depriving Assange of almost all contact with the outside world, including access to the internet, and telephone and launching a media demonisation campaign that portrayed him as abusing his cat and smearing faeces on the wall (pp. 207-9).

At the same time, the CIA worked with the embassy’s security firm to launch a sophisticated, covert spying operation of Assange and all his visitors, including his doctors and lawyers (p. 200). We now know that the CIA was also considering plans to kidnap or assassinate Assange (p. 218).

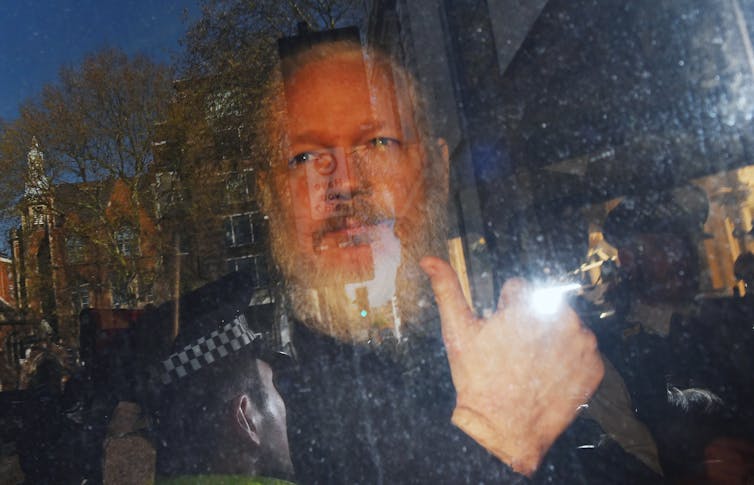

Finally in April 2019, having stripped Assange of his citizenship and asylum – in flagrant violation of international and Ecuadorean law – Quito let the British police seize him (p. 213).

He was dragged into the daylight, his first public appearance in many months, looking unshaven and unkempt – a “demented looking gnome“, as a long-time Guardian columnist called him.

In fact, Assange’s image had been carefully managed to alienate the watching world. Embassy staff had confiscated his shaving and grooming kit months earlier.

Meanwhile, Assange’s personal belongings, his computer, and documents were seized and transferred not to his family or lawyers, or even the British authorities, but to the US – the real author of this drama (p. 214).

That move, and the fact that the CIA had spied on Assange’s conversations with his lawyers inside the embassy, should have sufficiently polluted any legal proceedings against Assange to require that he walk free.

But the rule of law, as Melzer keeps noting, has never seemed to matter in Assange’s case.

Quite the reverse, in fact. Assange was immediately taken to a London police station where a new arrest warrant was issued for his extradition to the US.

The same afternoon Assange appeared before a court for half an hour, with no time to prepare a defence, to be tried for a seven-year-old bail violation over his being granted asylum in the embassy (p. 48).

He was sentenced to 50 weeks – almost the maximum possible – in Belmarsh high-security prison, where he has been ever since.

Apparently, it occurred neither to the British courts nor to the media that the reason Assange had violated his bail conditions was precisely to avoid the political extradition to the US he was faced with as soon as he was forced out of the embassy.

‘Living in a tyranny’

Much of the rest of Melzer’s book documents in disturbing detail what he calls the current “Anglo-American show trial”: the endless procedural abuses Assange has faced over the past three years as British judges have failed to prevent what Melzer argues should be seen as not just one but a raft of glaring miscarriages of justice.

Not least, extradition on political grounds is expressly forbidden under Britain’s extradition treaty with the US (pp. 178-80, 294-5). But yet again the law counts for nothing when it applies to Assange.

The decision on extradition now rests with Patel, the hawkish home secretary who previously had to resign from the government for secret dealings with a foreign power, Israel, and is behind the government’s current draconian plan to ship asylum seekers to Rwanda, almost certainly in violation of the UN Refugee Convention.

Melzer has repeatedly complained to the UK, the US, Sweden, and Ecuador about the many procedural abuses in Assange’s case, as well as the psychological torture he has been subjected to. All four, the UN rapporteur points out, have either stonewalled or treated his inquiries with open contempt (pp. 235-44).

Assange can never hope to get a fair trial in the US, Melzer notes. First, politicians from across the spectrum, including the last two US presidents, have publicly damned Assange as a spy, terrorist, or traitor and many have suggested he deserves death (p. 216-7).

And, second, because he would be tried in the notorious “espionage court” in Alexandria, Virginia, located in the heart of the US intelligence and security establishment, without public or press access (pp. 220-2).

No jury there would be sympathetic to what Assange did in exposing their community’s crimes. Or as Melzer observes: “Assange would get a secret state-security trial very similar to those conducted in dictatorships” (p. 223).

And once in the US, Assange would likely never be seen again, under “special administrative measures” (SAMs) that would keep him in total isolation 24-hours-a-day (pp. 227-9). Melzer calls SAMs “another fraudulent label for torture”.

Melzer’s book is not just a documentation of the persecution of one dissident. He notes that Washington has been meting out abuses on all dissidents, including most famously the whistleblowers Chelsea Manning and Edward Snowden.

Assange’s case is so important, Melzer argues, because it marks the moment when western states not only target those working within the system who blow the whistle that breaks their confidentiality contracts, but those outside it too – those like journalists and publishers whose very role in a democratic society is to act as a watchdog on power.

If we do nothing, Melzer’s book warns, we will wake up to find the world transformed. Or as he concludes: “Once telling the truth has become a crime, we will all be living in a tyranny” (p. 331).

The Trial of Julian Assange by Nils Melzer is published by Verso.

• First published by Middle East Eye

The post

The persecution of Julian Assange first appeared on

Dissident Voice.

This post was originally published on Dissident Voice.