The post Blak women are doing the work, are you listening? appeared first on IndigenousX.

This post was originally published on IndigenousX.

The post Blak women are doing the work, are you listening? appeared first on IndigenousX.

This post was originally published on IndigenousX.

On February 20, the New York Times published an article titled “Venezuelan Women Lose Access to Contraception, and Control of Their Lives.” This article attempts to distort reality, as it completely ignores the siege and aggressions the Venezuelan people currently subjected to.

For greater context, we should note that in 2012, Venezuela granted completely free access to safe and quality contraceptives, reaching a coverage of 22.16% in the national public health system. Access was nearly universal both due to the purchasing power of Venezuelans at the time and because both private and public health networks were subsidized up to 70% by the government, with funds guaranteed by the country’s foreign income.

The post Venezuelan Women Endure The ‘Sanctions’ With Their Bodies appeared first on PopularResistance.Org.

This post was originally published on PopularResistance.Org.

Policeman accused of sex trafficking, while 12,000 women and girls vanish in ‘shadow pandemic’

Judith Machaca was last seen on her way home from work in her home town of Tacna in southern Peru. The environmental engineering student had been working part-time at a mobile phone shop and would always send a message if she was going to be late.

The last text message from her phone was sent at 11pm on 28 November and the next day her distraught father reported the 20-year-old’s disappearance to the police. They sent him away, saying that she was probably with a boyfriend and would show up soon enough.

Related: ‘Shadow pandemic’ of violence against women to be tackled with $25m UN fund

By reporting a disappearance, you could be reporting it to the trafficker himself

No body, no crime

Continue reading…This post was originally published on Human rights | The Guardian.

Scheme distracts from rightful criticisms of police response to Clapham vigil, campaigners say

Plans to protect women by putting plainclothes police officers in nightclubs are bizarre, frightening and “spectacularly missing the point”, campaigners and charities have said.

The plans were outlined by the government as part of the steps it was taking to improve security and protect women from predatory offenders. Called Project Vigilant, the programme can involve officers attending areas around clubs and bars in plainclothes, along with increased police patrols as people leave at closing time.

Continue reading…This post was originally published on Human rights | The Guardian.

On International Women’s Day, there’s lots to celebrate in terms of the movements for gender equality around the world.

There’s been great progress in some places during the pandemic: Argentina’s abortion legalisation signified a huge victory for reproductive rights; Donald Trump was voted out of office; a transgender woman achieved a landmark victory for transgender rights in the US.

However, there has been a more sinister effect of coronavirus (Covid-19) for women. Increasingly, reports are finding that women are taking on the majority of childcare and home schooling, and have also been more likely to lose their jobs during the pandemic.

This has led to fears that the pandemic has hampered progress in gender equality. As a result, we must take extra care to ensure coronavirus recovery includes planning for recovering equality.

In July, the Office for National Statistics (ONS) released figures showing that women spent significantly more time on childcare in a day. A third of women subsequently said their mental health had suffered because of home schooling.

A further study by University College London (UCL) found that women were more likely to have given up working to look after and educate children during lockdowns.

Emla Fitzsimons, a research author and professor at UCL’s Institute of Education, said:

Many mothers who have put their careers on hold to provide educational support for their children will need to adjust again once schools reopen and the furlough scheme tapers off.

These figures show that women who have reduced work hours to help their children will need support to get back to the workplace. While reports show men are taking on more housework than they did decades ago, we cannot settle for women being the default for childcare responsibilities.

Children are returning to school, but the future remains uncertain as to whether they will stay there; men must step up to take on an equal share of childcare.

In addition, women have also been more likely to lose their jobs or be furloughed during coronavirus. Women are more likely to work in sectors such as hospitality, arts, and retail, which have been more likely to have to lay off workers over the course of the pandemic.

For example, Debenhams and Arcadia, both recently bought by online companies, are likely to shed most of their store employees. At those stores alone, 77% and 84.5% of staff respectively were women.

In the arts and entertainment sector, there was a two-fifths drop in the number of Black women working.

This leaves many women in a precarious position. And it further risks decades of progress in increasing women’s representation in the workforce. In this case, the government has the power to tackle this by maintaining furlough as long as it takes industries like hospitality to get back on their feet. This would protect industries from having to shed jobs that are likely to be held by women.

Most terrifyingly, coronavirus has led to an increase in domestic abuse across the world. The UK saw a 49% rise in domestic abuse calls made to the police in just the first month after restrictions began.

The United Nations (UN) has called the increase in domestic violence a ‘shadow pandemic’, urging global action to address the increase as countries map out recovery.

While the government has announced £19m in funding to tackle domestic abuse, domestic violence charity Women’s Aid has called for more funding from the UK government to help women effectively.

Women’s Aid chief executive Farah Nazeer said:

Specialist women’s domestic abuse services continue to face a funding crisis, with funding cuts and poor commissioning decisions failing to keep them secure. Women’s Aid estimates that £393m is required for lifesaving refuges and community-based services in England, alongside ring-fenced funding for specialist services led ‘by and for’ Black and minoritised women, disabled women and LGBT+ survivors.

However next year only £165 million will be delivered, with an additional £19 million announced today for work with perpetrators and ‘respite rooms’ for homeless women. We urge the government to provide further details of this funding, as it’s unclear what ‘respite rooms’ are.

This shortfall of over £200 million will mean that women and children will be turned away from the lifesaving support they need.

Without action, women are increasingly suffering violence in their own homes. We cannot allow this pandemic to mean less support for them.

In a recent survey by Mumsnet, more than half of the respondents said they believed gender equality was “in danger of going back to the 1970s” – a horrifying thought.

If we look to previous health emergencies, the outlook is bleak: one year removed from Sierra Leone’s Ebola outbreak, 17% of women have returned to work compared to 63% of men. An outbreak of Zika in Brazil five years ago still sees 90% of women who have a child with Congenital Zika Syndrome out of work.

With that possibility in front of us, we must take this as a call to lobby for women’s rights globally – in the home and in the workplace. The fight for gender equality is a fight parallel to and inseparable from the justice called for by the Black Lives Matter movement, by campaigns for economic equality – we cannot allow it to go backwards.

Featured image via Pixabay/Standsome

This post was originally published on The Canary.

Millions of women around the world are taking to the streets today to mark International Women’s Day — in a year where women have been disproportionately impacted by rising poverty, unemployment and violence during the pandemic. We hear voices from protests in the Philippines, Mexico and Guatemala.

This is a rush transcript. Copy may not be in its final form.

AMY GOODMAN: Millions of women around the world are taking to the streets today to mark this International Women’s Day — in a year where women have been disproportionately impacted by rising poverty, unemployment and violence during the pandemic.

In the Philippines, hundreds of women led a rally outside the presidential palace in Manila, chanting “Stop killing us.” Protesters are demanding the resignation of President Duterte. This is an advocate with the women’s rights group Gabriela.

JOMS SALVADOR: We would like to underline the fact that we are in a deeper crisis and we are facing a virus far deadlier than COVID. And it is the rotten, anti-people, pro-foreign interest and fascist, macho-fascist presidency and leadership of President Duterte.

AMY GOODMAN: In India, thousands of women farmers led hunger strikes and sit-ins at multiple sites on the outskirts of New Delhi, where tens of thousands of farmers have camped out for over three months protesting new neoliberal agricultural laws promoted by Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

In Australia, hundreds of workers, from nurses to teachers, gathered outside a government building in Sydney condemning violence against women and calling for greater gender equality and protections in the workplace.

In Mexico, the names of femicide victims were painted on security barriers placed in front of the presidential palace in Mexico City’s Zócalo ahead of a massive march today. Over 900 femicides were reported in Mexico last year alone.

MARCELA: [translated] We believe that it is important that they are written because the fight is for them. What we want is to ask for justice, for the people to be aware and for the president who lives here to understand that we are fighting because they are killing us.

AMY GOODMAN: In Guatemala City, hundreds of women and girls gathered outside the presidential palace to protest the rising number of femicides. After a march, advocates filled the Constitutional Plaza for a music festival, where activists danced and artists painted colorful murals commemorating the victims of femicide. This is one of the protesters.

PROTESTER: [translated] I dream that women are free from violence, that I can go out on the streets and be at peace, know that I’m going to come back home alive. We want the liberation of women from this patriarchal system.

AMY GOODMAN: International Women’s Day also marks four years since 41 girls were burnt to death inside an orphanage near Guatemala City for protesting sexual and physical violence.

This post was originally published on Latest – Truthout.

The post Parliament house sexual assaults, Australia you have a problem appeared first on IndigenousX.

This post was originally published on IndigenousX.

Updated on March 1, 2022: This piece was originally published on March 1, 2020, and has been updated to reflect the latest statistics.

Women’s History Month is an occasion to recognize advancements in gender equality and the achievements of women around the world in everything from media to science to criminal justice reform. But it’s also an occasion to acknowledge the work that needs to be done to truly establish gender equality in all aspects of life.

When it comes to incarceration and wrongful conviction, women face unique challenges both as directly impacted individuals and as the people who shoulder much of the financial and caretaking burden when loved ones are incarcerated.

Yet conversations about mass incarceration have often overlooked women, even though they are the fastest-growing group of incarcerated people, according to the Prison Policy Initiative.

Here are eight important facts about women and incarceration in the U.S. that you should know.

1. The population of women in state prisons has grown at more than twice the rate of the population of men in state prisons.

Women account for approximately 10% of the 2.3 million incarcerated people in the U.S., but despite making up a relatively small percentage of the overall incarcerated population, the number of women in state prisons is growing at a much faster rate than men. Between 1978 and 2015, the female state prison population grew by 834%.

2. Women are disproportionately incarcerated in jails where more than half of them have not yet been convicted of a crime and are still presumed innocent.

About 231,000 women were detained in jails and prisons across the U.S. in 2019, with approximately 101,000 being held in local jails. Among the women in these local jails, 60% had not yet been found guilty of a crime and were awaiting trial. One contributing factor to the high rate of women in jails pre-trial is that women are less likely to be able to afford to make bail or to pay other fees and fines that may prevent them from returning home to await their trials, according to the Vera Institute of Justice.

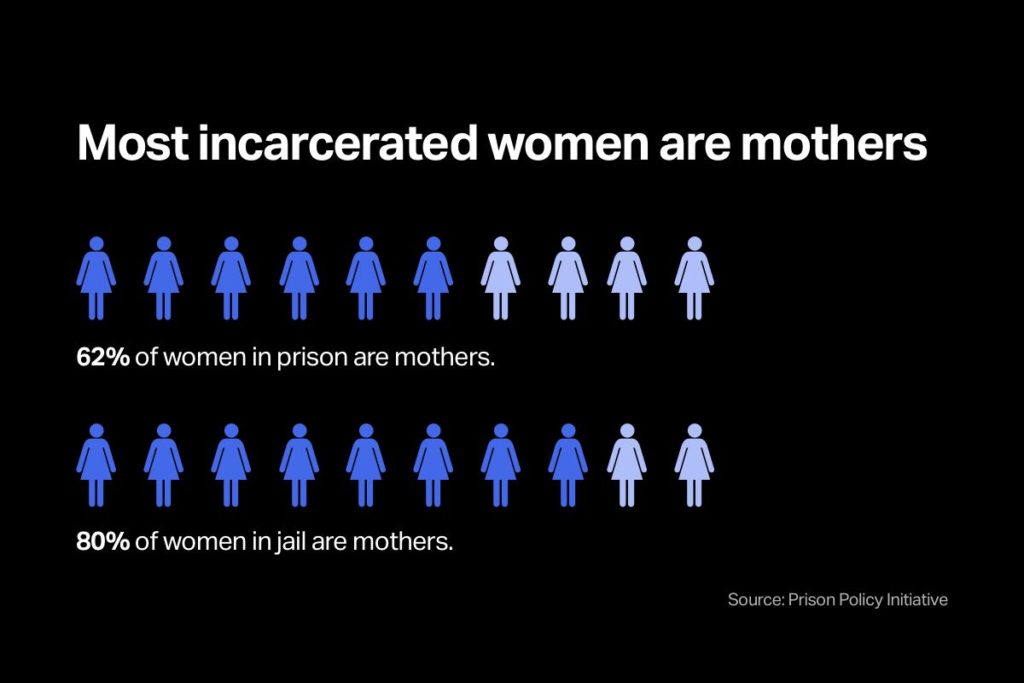

3. Most incarcerated women are mothers.

More than 60% of women in prison have children under the age of 18 and nearly 80% of women in jail are mothers, the Prison Policy Initiative reports. Incarcerated women tend to be single parents or primary caretakers more often than incarcerated men, according to the Vera Institute. This means that their incarceration is likely to have a major impact on their children and family members. Many children of incarcerated mothers are placed in foster care.

Women are more likely to be incarcerated far away from their children because there are fewer women’s prisons than men’s making it difficult and costly for their children and family members to see them in person. After their incarceration, it can be extremely challenging for mothers to reunite with children placed in foster care.

4. Two hundred and fifty-eight women have been exonerated since 1989.

Of the 2,991 people who have been exonerated in the last three decades, about 9% were women, according to data from the National Registry of Exonerations.

5. Most female exonerees were convicted of crimes that never occurred.

About 71% of women exonerated in the last three decades were wrongfully convicted of crimes that never took place at all, according to data from the National Registry of Exonerations. These “crimes” included events later determined to be accidents, deaths by suicide, and crimes that were fabricated.

6. More than a quarter of female exonerees were wrongly convicted of harming a child in their care.

About 28% of female exonerees were convicted of crimes in which the victim was a child, according to data from the National Registry of Exonerations.

These include nine women who were convicted of shaking a baby to death. Thousands of people have been accused, and many convicted, of harming children by violently shaking them and causing a condition known as Abusive Head Trauma (previously referred to as “shaken baby syndrome”). However, scientists and medical experts have said the three symptoms used to diagnose Abusive Head Trauma — diffuse brain swelling, subdural hemorrhage and retinal hemorrhages — can all result from many other causes, including diseases, falling at home, and even the birthing process, and that the concept of “shaken baby syndrome” has never been validated.

7. Only 13 women have been exonerated with the help of DNA evidence.

DNA evidence was central to proving the innocence of five of these women, and helped to prove the innocence of the eight other women together with other essential factors, according to data from the National Registry of Exonerations.

The number of women exonerated with the help of DNA evidence is significantly lower than the number of men exonerated by DNA evidence — more than 300 — in large part because of the types of crimes of which women tend to be convicted. More men are convicted of crimes like rape and murder, in which more DNA evidence is likely to be left behind, than women.

8. False or misleading forensic evidence contributed to the wrongful convictions of 94 women who have since been exonerated.

Errors in forensic testing, information based on unreliable or unproven forensic methods, fraudulent information or evidence, and forensic information presented with exaggerated and misleading confidence can all contribute to wrongful convictions. Such factors contributed to the wrongful convictions of at least 94 women, whose convictions have been overturned over the last three decades.

The post 8 Facts About Incarcerated and Wrongfully Convicted Women You Should Know appeared first on Innocence Project.

This post was originally published on Innocence Project.

Home Office accused of betrayal over network of new asylum-seeker centres

A new network of immigration detention units for women is being quietly planned by the Home Office, contrary to previous pledges to reform the system and reduce the number of vulnerable people held.

An initial detention centre, based in County Durham on the site of a former youth prison, will open for female asylum seekers this autumn.

Related: Britain’s immigration detention: how many people are locked up?

Continue reading…This post was originally published on Human rights | The Guardian.

Civil war has drastically cut support services for women already at high risk of violence while displacing others who are now vulnerable to armed groups

Rima* was married the year civil war erupted in Yemen. She was 15 and for much of the time over the next five years, her husband kept her chained to a wall in their home in central Yemen. “He didn’t treat me as a wife, he treated me as a slave,” says the 21-year-old.

An aunt eventually took pity on Rima, taking her to a psychosocial support centre in the town of Turba, 90 miles (145km) north-west of Aden. According to a doctor there, Rima now suffers from a neurological disorder brought on by the constant beatings.

Related: Yemen: in a country stalked by disease, Covid barely registers

I want to be a lawyer when I grow up, because I feel I didn’t have any rights, because I didn’t get justice

In the UK, call the national domestic abuse helpline on 0808 2000 247, or visit Women’s Aid. In Australia, the national family violence counselling service is on 1800 737 732. In the US, the domestic violence hotline is 1-800-799-SAFE (7233). Other international helplines may be found via www.befrienders.org

Continue reading…This post was originally published on Human rights | The Guardian.

Today is International Day of Women and Girls in Science, an occasion established by the United Nations, to celebrate the achievements and contributions of female scientists. That includes women like Rosalind Franklin, who, for many years, went uncredited for her crucial contribution to the discovery of DNA’s structure.

While gender equality in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) fields has improved in recent decades, globally, less than 30% of researchers are women, according to the UNESCO Institute for Statistics. In the United States, women make up just 28% of those working in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) industries.

At the Innocence Project, we are lucky to have several female scientists from all different backgrounds on our team. Each brings their unique perspective to the work of our policy, research, and legal teams, and helps ensure that everything we do is rooted in science.

Today, in solidarity with all women working in STEM fields and the young girls who dream of becoming scientists, we’re sharing the powerful stories of four inspiring female scientists at the Innocence Project.

Innocence Project Senior Staff Attorney Susan Friedman conducting a direct examination of a DNA expert via Zoom on behalf of Innocence Project client Robert DuBoise. (Image: Casey Brooke Lawson/The Innocence Project)

Advice to women and girls: Find what you love and don’t let anyone stand in your way or persuade you that you aren’t smart enough, good enough, or capable enough to do it.

I was always a super curious kid. I loved figuring out how things worked. But I think what really lead me into science is that my mom passed away when I was very little — I was 6 — and I didn’t really understand what happened to her at the time. That led me to really want to learn about science and, initially, about cancer development. I wanted to help people through science.

In high school, I was in a special science program that was predominantly male. And so when I was going to college, I made a purposeful choice to go to a women’s college, Mount Holyoke. I was really lucky in that most of my professors in college were these really smart, badass women with PhDs from Harvard, and all my classmates were smart, and I felt like women could do anything and everything.

I went to graduate school at Mount Sinai Medical School and then law school thinking I would either do something in health care like work for the FDA (U.S. Food and Drug Administration) or regulatory work around pharmaceuticals. I didn’t think I would be a criminal defense attorney.

During my first year of law school, the National Academy of Sciences released a major report on forensic science and it just totally blew my mind. Because of my background as a biochemist, I had done DNA testing and all of that stuff, and I got really into the report. It just shocked me that there had been such a lack of science in the criminal legal system. I was hooked.

I think having that science background has been a tremendous help and makes me a better lawyer because almost every case that I litigate involves DNA evidence or other evidence like fingerprints. So I’m always reading scientific studies and looking at the data, and it’s a huge benefit to have a science background because it’s alarming how few people in the criminal legal system actually understand the science.

It just shocked me that there had been such a lack of science in the criminal legal system.

It’s getting better now, but when I first got out of law school, I was really surprised that there are people prosecuting people using DNA evidence without actually understanding what that evidence means. And frequently what that meant is that they would accidentally misstate the evidence. But I think the reality is that if you are going to work in the criminal legal space, then you have an ethical obligation to understand these concepts and human biology, you need to take continuing legal education, you need to read the papers, take classes, and engage with the material.

Sarah Chu, Innocence Project senior advisory on forensic science policy, with her daughter (Image: Courtesy of Sarah Chu)

Advice for women and girls: Don’t second guess what you’re passionate about and if STEM is what excites you, try to seek mentors who are like you, and if you can’t, take advantage of any mentorship opportunities you have.

Growing up my parents kind of set the expectation that I would either become a doctor or an engineer. In Taiwan, my mom was a physics and calculus teacher and my dad was a nuclear engineer. Then we moved to the Silicon Valley, so growing up I was surrounded by people in the tech sector, and there was kind of an expectation that you were going to do something STEM-related.

But I knew from an early age that I would have to work hard to do that. When I was in elementary school, my mom went back to school to get an engineering degree to get into a second career. And one night I saw her crying because a professor told her she was taking up a seat that should have been a man’s. He said he was reserving A’s in his class for the men because they were the ones who were going to do something with their degrees.

My mom told me that as a woman, and as an Asian person, that I would need to work twice as hard to be considered on equal par with a white man in the world. She went on to excel in her field, and what I really learned from her was to be persistent and to not let my own insecurities or imposter syndrome get in the way of taking advantage of an opportunity, because a man wouldn’t.

I started off pre-med and then I realized I really couldn’t stomach the gory stuff. So I thought then my path would be getting a PhD and doing research, and I joined a plant lab. There I had the formative experience of discovering something that contradicted general knowledge about how plants respond to droughts. I think at most labs, the principal investigator would have just told me I did the experiment wrong as an undergrad. But the postdoc I was working with said let’s do a few more repetitions, and we eventually realized we were finding something new. And so we got to publish a paper establishing our methodology and technique.

…what I really learned from her was to be persistent.

That experience really stuck with me and that really gave me a framework for thinking about forensic science in my work now. In forensic science, we have these disciplines where there’s a sense of what the science is, but it’s so important to actually do the testing and to validate those methods because it impacts people’s lives.

After that I worked in epidemiology, where I realized that what I love is developing knowledge and being at the cutting edge of something and doing something that impacts people. For a while I taught chemistry and physics in the New York City school system, but when I understood the challenges that my students were facing every day — like having to take care of four younger siblings or dealing with traumatic interactions with law enforcement — I thought that demanding that they turn in worksheets and homework was so secondary to all that.

I wanted to find a way to use my science degree and to do advocacy work that would make their lives better. Science has been my tool for realizing my passion for criminal justice reform. In order to do justice in this system, people in the criminal legal system need to understand the science, and we’re starting to see that with judges taking a more sophisticated look at evidence and how public defender offices across the country now have forensic units.

It can be so easy to dismiss something when you don’t understand it, but today with where we are that can no longer be what we do in the system.

Glinda Cooper, Innocence Project director of science and research

My job is really about making sure that our research is sound. That the data that we use is sound and accurate and that we apply the principles of science to our work. I think people have a tendency to cherry-pick data — it’s kind of human nature to hone in on the part that makes sense to you. But what we work hard to do is make sure that we’re comprehensive in our approach to looking at a study. It’s important to be aware of everything that data or a study is showing, that there is nuance — and that’s not just in science, but information, politics, everything.

But what I love about science is that it’s concrete. There are formulas, there are laws about nature and how it works, like gravity. I just find that very satisfying.

When I went to college, I wanted to major in chemistry and there were no women faculty members. The only female graduate students were nuns and it was like this message that you could only be in science if you forwent any other kind of relationship. There were professors that would make derogatory comments about women in large lecture halls and they were just accepted — no one even blinked an eye.

I went on to work in epidemiology, which actually generally has a lot more women. I think a lot has changed in 30 years and I hope that it’s a different environment for women studying science today, and that we don’t take that progress for granted.

Vanessa Meterko, Innocence Project research manager (Image: Courtesy of Vanessa Meterko)

Advice for women and girls: The essence of science is curiosity. Embrace your curiosity and just try things.

When I was a kid, I wanted to be a detective and obviously I’m not that today, but I think the desire behind that was an interesting in solving mysteries and I think that science is a way to do that — to solve mysteries of the natural world or human behavior.

I went to grad school and studied forensic psychology where I studied the phenomena of false confessions and I was really fascinated by that. After that I joined the Innocence Project team, almost 10 years ago, where my work is essentially using science to advance justice.

On a day-to-day basis that means collecting and organizing information about wrongful conviction cases — so literally reading through police and laboratory reports and trial transcripts and post-conviction motions and pleadings to understand patterns of wrongful convictions. And I also keep track of the academic literature around things like false confessions and cognitive biases in police investigations so that our work can be informed by the latest research.

I think this research is really important in explaining things that are hard for people to understand. Like I think it’s hard for people to wrap their head around why someone would falsely confess to something horrific that they didn’t do, but when you break it down to some of the underlying principles of psychology and what’s happening it becomes a lot easier to understand how it happens and why it happens more often that people think.

There are so many different ways we can contribute to advancing fairness and equity in the justice system, and scientists really are a part of that, and I think that’s important for people to know.

The post Four Inspiring Female Scientists Tell Us How They Ended Up at the Innocence Project appeared first on Innocence Project.

This post was originally published on Innocence Project.

Today is International Day of Women and Girls in Science, an occasion established by the United Nations, to celebrate the achievements and contributions of female scientists, which have historically been overlooked — like Rosalind Franklin, who, for many years, went uncredited for her crucial contribution to the discovery of DNA’s structure.

While gender equality in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) fields has improved in recent decades, globally, less than 30% of researchers are women, according to the UNESCO Institute for Statistics. In the United States, women make up just 28% of those working in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) industries.

At the Innocence Project, we are lucky to have several female scientists from all different backgrounds on our team. Each brings their unique perspective to the work of our policy, research, and legal teams, and helps ensure that everything we do is rooted in science.

Today, in solidarity with all women working in STEM fields and the young girls who dream of becoming scientists, we’re sharing the powerful stories of four inspiring female scientists at the Innocence Project.

Innocence Project Senior Staff Attorney Susan Friedman conducting a direct examination of a DNA expert via Zoom on behalf of Innocence Project client Robert DuBoise. (Image: Casey Brooke Lawson/The Innocence Project)

Advice to women and girls: Find what you love and don’t let anyone stand in your way or persuade you that you aren’t smart enough, good enough, or capable enough to do it.

I was always a super curious kid. I loved figuring out how things worked. But I think what really lead me into science is that my mom passed away when I was very little — I was 6 — and I didn’t really understand what happened to her at the time. That led me to really want to learn about science and, initially, about cancer development. I wanted to help people through science.

In high school, I was in a special science program that was predominantly male. And so when I was going to college, I made a purposeful choice to go to a women’s college, Mount Holyoke. I was really lucky in that most of my professors in college were these really smart, badass women with PhDs from Harvard, and all my classmates were smart, and I felt like women could do anything and everything.

I went to graduate school at Mount Sinai Medical School and then law school thinking I would either do something in health care like work for the FDA (U.S. Food and Drug Administration) or regulatory work around pharmaceuticals. I didn’t think I would be a criminal defense attorney.

During my first year of law school, the National Academy of Sciences released a major report on forensic science and it just totally blew my mind. Because of my background as a biochemist, I had done DNA testing and all of that stuff, and I got really into the report. It just shocked me that there had been such a lack of science in the criminal legal system. I was hooked.

I think having that science background has been a tremendous help and makes me a better lawyer because almost every case that I litigate involves DNA evidence or other evidence like fingerprints. So I’m always reading scientific studies and looking at the data, and it’s a huge benefit to have a science background because it’s alarming how few people in the criminal legal system actually understand the science.

It’s getting better now, but when I first got out of law school, I was really surprised that there are people prosecuting people using DNA evidence without actually understanding what that evidence means. And frequently what that meant is that they would accidentally misstate the evidence. But I think the reality is that if you are going to work in the criminal legal space, then you have an ethical obligation to understand these concepts and human biology, you need to take continuing legal education, you need to read the papers, take classes, and engage with the material.

Sarah Chu, Innocence Project senior advisory on forensic science policy, with her daughter (Image: Courtesy of Sarah Chu)

Advice for women and girls: Don’t second guess what you’re passionate about and if STEM is what excites you, try to seek mentors who are like you, and if you can’t, take advantage of any mentorship opportunities you have.

Growing up my parents kind of set the expectation that I would either become a doctor or an engineer. In Taiwan, my mom was a physics and calculus teacher and my dad was a nuclear engineer. Then we moved to the Silicon Valley, so growing up I was surrounded by people in the tech sector, and there was kind of an expectation that you were going to do something STEM-related.

But I knew from an early age that I would have to work hard to do that. When I was in elementary school, my mom went back to school to get an engineering degree to get into a second career. And one night I saw her crying because a professor told her she was taking up a seat that should have been a man’s. He said he was reserving A’s in his class for the men because they were the ones who were going to do something with their degrees.

My mom told me that as a woman, and as an Asian person, that I would need to work twice as hard to be considered on equal par with a white man in the world. She went on to excel in her field, and what I really learned from her was to be persistent and to not let my own insecurities or imposter syndrome get in the way of taking advantage of an opportunity, because a man wouldn’t.

I started off pre-med and then I realized I really couldn’t stomach the gory stuff. So I thought then my path would be getting a PhD and doing research, and I joined a plant lab. There I had the formative experience of discovering something that contradicted general knowledge about how plants respond to droughts. I think at most labs, the principal investigator would have just told me I did the experiment wrong as an undergrad. But the postdoc I was working with said let’s do a few more repetitions, and we eventually realized we were finding something new. And so we got to publish a paper establishing our methodology and technique.

That experience really stuck with me and that really gave me a framework for thinking about forensic science in my work now. In forensic science, we have these disciplines where there’s a sense of what the science is, but it’s so important to actually do the testing and to validate those methods because it impacts people’s lives.

After that I worked in epidemiology, where I realized that what I love is developing knowledge and being at the cutting edge of something and doing something that impacts people. For a while I taught chemistry and physics in the New York City school system, but when I understood the challenges that my students were facing every day — like having to take care of four younger siblings or dealing with traumatic interactions with law enforcement — I thought that demanding that they turn in worksheets and homework was so secondary to all that.

I wanted to find a way to use my science degree and to do advocacy work that would make their lives better. Science has been my tool for realizing my passion for criminal justice reform. In order to do justice in this system, people in the criminal legal system need to understand the science, and we’re starting to see that with judges taking a more sophisticated look at evidence and how public defender offices across the country now have forensic units.

It can be so easy to dismiss something when you don’t understand it, but today with where we are that can no longer be what we do in the system.

Glinda Cooper, Innocence Project director of science and research

My job is really about making sure that our research is sound. That the data that we use is sound and accurate and that we apply the principles of science to our work. I think people have a tendency to cherry-pick data — it’s kind of human nature to hone in on the part that makes sense to you. But what we work hard to do is make sure that we’re comprehensive in our approach to looking at a study. It’s important to be aware of everything that data or a study is showing, that there is nuance — and that’s not just in science, but information, politics, everything.

But what I love about science is that it’s concrete. There are formulas, there are laws about nature and how it works, like gravity. I just find that very satisfying.

When I went to college, I wanted to major in chemistry and there were no women faculty members. The only female graduate students were nuns and it was like this message that you could only be in science if you forwent any other kind of relationship. There were professors that would make derogatory comments about women in large lecture halls and they were just accepted — no one even blinked an eye.

I went on to work in epidemiology, which actually generally has a lot more women. I think a lot has changed in 30 years and I hope that it’s a different environment for women studying science today, and that we don’t take that progress for granted.

Vanessa Meterko, Innocence Project research manager (Image: Courtesy of Vanessa Meterko)

Advice for women and girls: The essence of science is curiosity. Embrace your curiosity and just try things.

When I was a kid, I wanted to be a detective and obviously I’m not that today, but I think the desire behind that was an interesting in solving mysteries and I think that science is a way to do that — to solve mysteries of the natural world or human behavior.

I went to grad school and studied forensic psychology where I studied the phenomena of false confessions and I was really fascinated by that. After that I joined the Innocence Project team, almost 10 years ago, where my work is essentially using science to advance justice.

On a day-to-day basis that means collecting and organizing information about wrongful conviction cases — so literally reading through police and laboratory reports and trial transcripts and post-conviction motions and pleadings to understand patterns of wrongful convictions. And I also keep track of the academic literature around things like false confessions and cognitive biases in police investigations so that our work can be informed by the latest research.

I think this research is really important in explaining things that are hard for people to understand. Like I think it’s hard for people to wrap their head around why someone would falsely confess to something horrific that they didn’t do, but when you break it down to some of the underlying principles of psychology and what’s happening it becomes a lot easier to understand how it happens and why it happens more often that people think.

There are so many different ways we can contribute to advancing fairness and equity in the justice system, and scientists really are a part of that, and I think that’s important for people to know.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Fashion brand to investigate the death of 20-year-old Jeyasre Kathiravel, reportedly killed by supervisor at Natchi Apparels

The family of a young garment worker at an H&M supplier factory in Tamil Nadu who was allegedly murdered by her supervisor said she had suffered months of sexual harassment and intimidation on the factory floor in the months before her death, but felt powerless to prevent the abuse from continuing.

H&M said it is launching an independent investigation into the killing of Jeyasre Kathiravel, a 20-year-old Dalit garment worker at an H&M supplier Natchi Apparels in Kaithian Kottai, Tamil Nadu, who was found dead on 5 January in farmland near her home.

Related: Racism is at the heart of fast fashion – it’s time for change | Kalkidan Legesse

Continue reading…This post was originally published on Human rights | The Guardian.

Family of women’s rights advocate, found dead in Canadian lake, call for police to reopen investigation

It was the homecoming they never wanted. Five years ago, Karima Baloch fled Pakistan after her work as a prominent human rights activist put her life in danger. On Sunday morning, on the tarmac of Karachi airport, she was returned to her family at last.

But though she lay lifeless in a wooden coffin, her body was confiscated by Pakistani security officials for hours. Then her home town in Balochistan was placed under the control of paramilitary forces, a curfew was imposed on the region and mobile services were suspended, all to prevent thousands turning out for her funeral on Monday. It was clear that, even in death, Pakistan viewed Baloch as a threat to national security.

Related: Pakistan: where the daily slaughter of women barely makes the news | Mohammed Hanif

Video: Relatives & close family friends were allowed to participate in the last funeral prayers of #KarimaBaloch. The huge participation of local women can also be seen in this video. People across the Balochistan were not allowed to farewell their leader.@Gulalai_Ismail pic.twitter.com/mTw6iP3rJG

Continue reading…This post was originally published on Human rights | The Guardian.

Bill Moyers sit down with Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg to discuss the most pressing global issues faced by present-day women leaders. Continue reading

The post Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg in Conversation with Bill Moyers appeared first on BillMoyers.com.

This post was originally published on BillMoyers.com.

We meet an immigration judge who rejected nearly every asylum case that came before her, then follow a transgender woman as she tries to claim asylum. Finally, we go to Turkey, where young Afghan women are trying to leave their past behind.

Don’t miss out on the next big story. Get the Weekly Reveal newsletter today.

This post was originally published on Reveal.

He seemed to confess to the crime, twice to his ex-girlfriend, once to police. But prosecutors never charged him. The reasons why show how rape myths continue to influence how justice is meted out in America. Reported in partnership with Newsy and ProPublica.

This post was originally published on Reveal.

When police closed the rape case against Bryan Kind, they made it look like it had been solved. But he never was arrested – or even charged. We team up with Newsy and ProPublica to investigate how police across the country make it seem like they’re solving more rape cases than they actually are.

Don’t miss out on the next big story. Get the Weekly Reveal newsletter today.

This post was originally published on Reveal.

In 2010, Brad McGahey was sentenced to a year in prison for buying a stolen horse trailer. But when he went before a judge, he was told he was going to carry out his sentence by working instead, through a program called CAAIR, or Christian Alcoholics & Addicts in Recovery.

McGahey wasn’t addicted to anything at the time of his sentencing. Hundreds of men are sent to CAAIR in lieu of a prison sentence each year. The program promises recovery from addiction for participants, but most of their time is spent working at a chicken processing plant, where they pull guts and feathers from slaughtered chickens and prepare them for distribution to companies such as Walmart, KFC and PetSmart.

This post was originally published on Reveal.