He seemed frustrated. While Scott Morrison’s international colleagues at the Leaders Summit on Climate were boastful in what their countries would do in decarbonising the global economy, Australia’s feeble contribution was put on offer. Unable to meet his own vaccination targets, the Australian prime minister has decided to confine the word “target” in other areas of policy to oblivion. Just as the term “climate change” has been avoided in the bowels of Canberra bureaucracy, meeting environmental objectives set in stone will be shunned.

Ahead of the summit, Nobel Prize laureates had added their names to a letter intending to ruffle summit participants. Comprising all fields, the 101 signatories urged countries “to act now to avoid a climate catastrophe by stopping the expansion of oil, gas and coal.” Governments had “lagged, shockingly, behind what science demands and what a growing and powerful people-powered movement knows: urgent action is needed to end the expansion of fossil fuel production; phase out current production; and invest in renewable energy.”

Deficiencies in the current climate change approach were noted: the Paris Agreement, for instance, makes no mention of oil, gas or coal; the fossil fuel industry was intending to expand, with 120% more coal, oil and gas slated for production by 2030. “The solution,” warn the Nobel Laureates, “is clear: fossil fuels must be kept in the ground.”

To Morrison and his cabinet, these voices are mere wiseacres who sip coffee and down the chardonnay with relish, oblivious to dirty realities. His address to the annual dinner of the Business Council of Australia took the view that Australia would “not achieve net zero in the cafes, dinner parties and wine bars of our inner cities.” Having treated environmental activism as delusionary, he suggested that industries not be taxed, as they provided “livelihoods for millions of Australians off the planet, as our political opponents sought to do when they were given the chance.”

US President Joe Biden had little appetite for such social distinctions in speaking to summit participants. (Unfortunately for the President, the preceding introduction by Vice President Kamala Harris was echoed on the live stream, one of various glitches marking the meeting.) After four years of a crockery breaking retreat from the subject of climate change, this new administration was hoping to steal back some ground and jump the queue in combating climate change. The new target: cutting greenhouse gas emissions by half from 2005 levels by 2030.

Biden wished to construct “a critical infrastructure to produce and deploy clean energy”. He saw workers in their numbers capping abandoned oil and gas wells and reclaiming abandoned coal mines. He dreamed of autoworkers in their efforts to build “the next generation of electric vehicles” assisted by electricians and the installing of 500,000 charging stations.

US Secretary of State Antony Blinken laboured the theme of togetherness in his opening remarks: “We’re in this together. And what each of our nations does or does not do will not only impact people of our country, but people everywhere.” But Blinken was also keen, at least in terms of language, to seize some ground for US leadership. “We want every country here to know: We want to work with you to save our planet, and we’re all committed to finding every possible avenue of cooperation on climate change.”

A central part of this policy will involve implementing the Climate Finance Plan, intended to provide and mobilise “financial resources to assist developing countries reduce and/or avoid greenhouse gas emissions and build resilience and adapt to the impacts of climate change.”

While solidarity and collaboration were points the Biden administration wished to reiterate, ill-tempered political rivalries were hard to contain. On April 19, Blinken conceded during his address to the Chesapeake Bay Foundation that China was “the largest producer and exporter of solar panels, wind turbines, batteries, electric vehicles.” It held, he sulkily noted, almost “a third of the world’s renewable energy patents.”

Environmental policy, in other words, had to become the next terrain of competition; in this, a good degree of naked self-interest would be required. “If we don’t catch up, America will miss the chance to shape the world’s climate future in a way that reflects our interests and values, and we’ll lose out on countless jobs for the American people.” Forget bleeding heart arguments about solidarity and collective worth: the US, if it was to win “the long-term strategic competition with China” needed to “lead the renewable energy revolution.”

Others in attendance also had their share of chest-thumping ambition. The United Kingdom’s Boris Johnson was all self-praise about his country having the “biggest offshore wind capacity of any country in the word, the Saudi Arabia of wind as I never tire of saying.” The country was half-way towards carbon neutrality. He also offered a new target: cutting emissions by 78 percent under 1990 levels by 2035. Wishing to emphasise his seriousness of it all, Johnson claimed that combating climate change was not “all about some expensive politically correct green act of ‘bunny hugging’.”

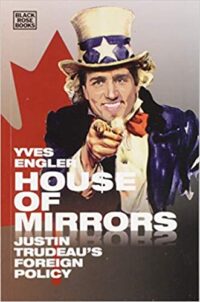

Canada also promised a more ambitious emissions reduction target: the Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) would be reduced by 40-45 percent below 2005 levels by 2030. “Canada’s Strengthened Climate Plan,” stated Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, “puts us on track to not just meet but to exceed our 2030 emissions goal – but we were clearly aware that more must be done.”

Brazil’s President and climate change sceptic Jair Bolsonaro chose to keep up appearances with his peers, aligning the posts to meet emissions neutrality by 2050. This shaved off ten years from the previous objective. He also promised a doubling of funding for environmental enforcement. Fine undertakings from a political figure whose policies towards the Amazon rainforest have been vandalising in their destruction.

Japan’s Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga also threw in his lot with a goal of securing a 46 percent reduction by 2030. (The previous target had been a more modest 26 percent reduction based on 2013 levels.) This did little to delight Akio Toyoda, president of Toyota Motor. “What Japan needs to do now,” he warned, “is to expand its options for technology.” Any immediate bans on gasoline-powered or diesel cars, for instance, “would limit such options, and could also cause Japan to lose its strengths.”

Toyoda’s sentiments, along with those of Japan’s business lobby Keidanren, would have made much sense to Morrison. In a speech shorn of ambition, the Australian prime minister began to speak with his microphone muted. Then came his own version of ambitiousness, certain that Australia’s record on climate change was replete with “setting, achieving and exceeding our commitments”.

It was not long before he was speaking, not to the leaders of the world, but a domestic audience breast fed by the fossil fuel industries. Australia was “on the pathway to net zero” and intent on getting “there as soon as we possibly can, through technology that enables and transforms our industries, not taxes that eliminate them and the jobs and livelihoods they support and create, especially in our regions.” His own slew of promises: Australia would invest in clean hydrogen, green steel, energy storage and carbon capture. The US might well have Silicon Valley, but Australia would, in time, create “Hydrogen Valleys”.

With such unremarkable, even pitiable undertakings, critics could only marvel at a list of initiatives that risk disappearing in the frothy stew. “Targets on their own, won’t lead to emission cuts,” reflected Greenpeace UK’s head of climate, Kate Blagojevic. “That takes real policy and money. And that’s where the whole world is still way off course.” Ahead of COP26 at Glasgow, Morrison will be hoping that the world remains divided and very much off course.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.