There’s a tremendous power in this place, in this land, and I think that power really changes people’s lives.

— Frank Boyden, Sitka Center for Art and Ecology.

A large number of the most creative, skilled, and savvy people in the country are out of jobs simultaneously. How can we harness that resource and develop collaborative projects and programs for them that might foster interdisciplinary work, enhance skills, and result in innovation in process and product? Perhaps this is the time to incubate a ‘Creative Economy 2.0’ across the United States that is inclusive, interdisciplinary, and intersectoral.

— Michael Seman, an assistant professor of arts management at Colorado State University’s LEAP Institute for the Arts

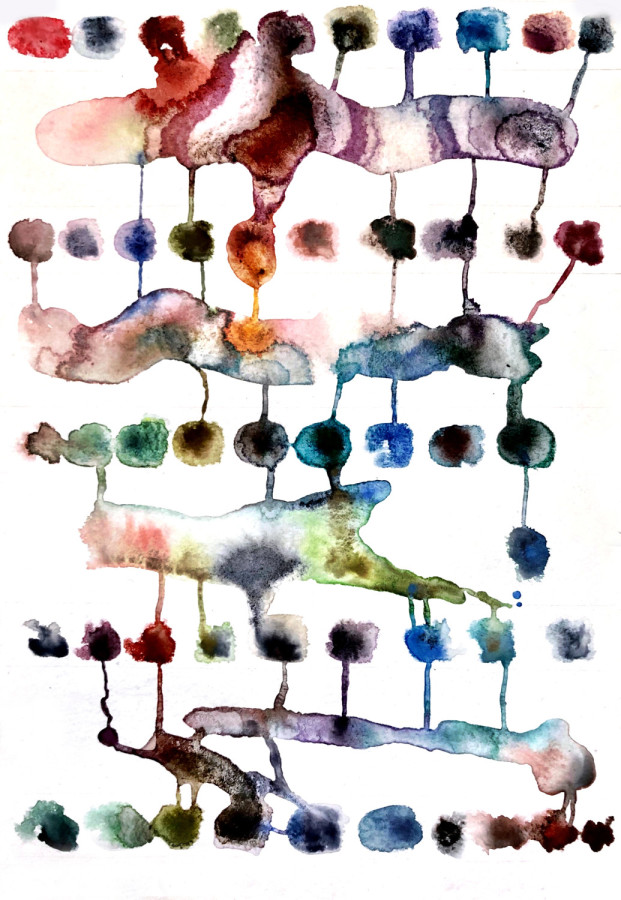

[New Earth 15, Daniela Molnar]

Here’s a foundational question roiling inside creative people’s brains — What does the artworld look like now, during the economic bust and lockdown, and for the future?

For me, I go back to the concept of duende — Goethe, who in speaking of Paganini, hit on a definition of the duende: “A mysterious force that everyone feels and no philosopher has explained.”

After posing this and other framing questions (with that idea of a spirit/muse/ force, duende, as my talisman), I luckily have been gifted artists’ feedback and interviews, after initially receiving a few crickets and a couple of snarky diatribes about why journalists suck (yes, we are artful artists, too).

Unfortunately, many artists who have some cash savings to fall back on, or housing, and that old time religion of being a trust fund baby, or even parents and uncles and aunts with some semblance of family connectivity, a spare office and bedroom, and the like, they are so mired in the “anyone but Trump” disease, and they sound so-so much like those elite NPR types who believe they are so tied to the fabric of the country, that these conversations about the death of art are a bit problematic.

Many believe that the tough will get going, and that a little disruption never hurt anyone, and of course, they are absolutely wrong-wrong-wrong.

Places like the UK and other places within the EU have study after study looking at the upheaval see death, the end of the road, depression, and just throwing in both the artist towel and other towels.

Part Two to this is with David Rovics, an artist in Portland, who writes for Dissident Voice about his music career and his fight for rent control. Here, some of his writings at DV.

My intent is not to having a pissing contest between those who have (white privilege, male or female) and those who do not have, but this discussion about who controls the narrative, the media, the press, the arts, well, i courses through the art world big time now, during, and soon, after, Covid-Hysteria/Covid Reset, and it certainly had been coursing through this society for decades.

Yes, we expect artists to starve, and we expect that the master of the universe and sometimes the most insipid ones, to determine the value of something, and the investment of both intellectual space and time and economic space and time in the arts.

This is not about the value of, say, a piece titled, “Piss Christ,” or Robert Mapplethorpe’s work or Laurie Anderson’s performance. This is about the value of life, which is in so many ways for a socialist revolutionary what you do that is good and deeply redeeming as a person connecting ideas to society. Art is just that, and sure, the internal demons and muses of individual artists sometimes prevail, and the art many times seems self-indulgent and narrowly personal.

But if we had a choice between Elon Musk types, Google “creative” types, all the Military Industrial Complex types, either slugs and leeches directly tied to munitions and death planes, or those very loosely tied to the killing mercenary machine of the US on so many levels, well, I’d take a bi-polar, oddly self-absorbed artist over any of the other thieves of hope and dreams and lives in Capitalism.

Here, a cast of people I interviewed. Not surprisingly, this piece was to be a paid gig piece, but alas, the publication caved, even though we had agreed upon the general idea of the piece. No kill fee, nothing, just a “we can’t and won’t use this piece since it deviates too much from our vision and mission of . . . . . .” You can fill in that blank. The media and publishing and newspaper and magazine landscape is, for all intents and purposes, dead and dying, while we have to listen to the putrid multi-million dollar contracts for the Obama’s of the world, or the Trumpies, or all the others who are not writers or artists.

You might tell I am mad, and this is the disenfranchisement of writers in our society, and the sting of rejection is nothing compared to the spinelessness of the entire field.

Thanks to the pantheist originator in the heavens for Dissident Voice.

Cast of players*

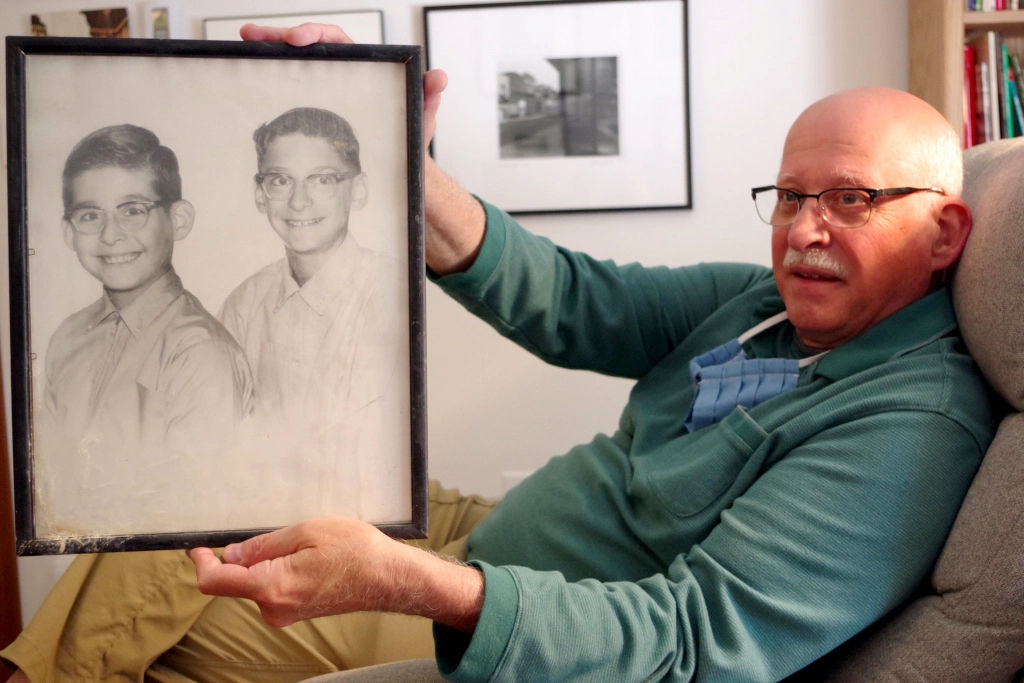

The Collector: Duane Snider, with more than 40 years collecting (totalling 247) individual art pieces from PNW creators, who says his life is a living on-going work of art (Waldport, OR, 2 years)

The Non-profit Impresario – Alison Dennis, executive director of the Sitka Center for Art and Ecology, whose roots are East Coast, Bennington College, with writing and art coursework (Cascade Head, OR, 2 years)

The Painter: Chuck Bloom, with a truckload of surrealistic and Tim Burton-esque wonderful (Portland, 19 years), who is self-described as the only LGBTQ board member on the Regional Arts & Culture Council (Portland, OR, 14 years)

Educator-Activist Artist: Daniela Molnar, self-described as visual artist/poet/wilderness guide/educator/essayist/activist/eternal student (13 years teaching at Pacific Northwest College of Art, Portland, OR)

Photo credit: Genaro Molina for the LA Times

*Note: Each cast member deserves his or her own New Yorker-like feature!

Art Not in a Political Vacuum (no matter how hard artists try and not be political)

I easily extrapolate from the cast of players this fact: 2020 represents a “new normal,” or a new “abnormal” for the world of arts.

Daniela sees these times as magnification of feedback loops and more/greater shifts in how we confront colliding breakdowns in politics, the environment, the economy and the arts. She concedes there were hard, dangerous times 13 years ago when she first started teaching in Portland. “What’s changed for me is my age and awareness, I suppose. These crises shifts challenge us more and more. Thirteen years ago, there weren’t Nazi rallies like we see under Trump. I don’t feel safe going out in public as a Jewish woman.”

As both artist and educator, Molnar tells me she has soured on higher education, lamenting how students and faculty are constantly being exploited. She reiterates what a lot of writers and visual artists have said time immemorial – you don’t need a college degree to be a writer or artist.

For New York-raised Molnar, she is “super grateful” her education took place in a time and manner where she incurred no debt. “I wasn’t treated as a consumer.”

In a Closet in a Small Town

Bloom’s roots go back to Bloomdale, a super small hamlet an hour south of Toledo, Ohio. He ended up in a private college, Mt. Union. His college loan debt is $80,000.

“Artists are struggling like they haven’t before. The energy to be creative has been drained by politics, Covid19, and now the fires. There’s a real sense of hopelessness. I go into the studio and say to myself – ‘This is pointless.’”

He ended up with his partner, Patrick (they met at Kent State), in Maui, working in an at-risk youth art program, as well as Borders Books.

His husband Patrick had just left the world of Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell US Navy when they met after answering newspaper ads. When they first came to Portland, artists could live downtown and afford a junky studio, Chuck says. “I really noticed the changes in 2007. A lot of people left the Pearl.”

Bloom’s seen less diversity in the Portland arts scene than he first anticipated, emphasizing how he used to hold high the concept of an art community being progressive. “The people I have come to know are not really liberal. I am one of the artists discovering the truth that the liberalness in Portland is kind of fake.”

How this illiberalness plays out is those controlling the art scene are holding back artists who want to not only question capitalism, but the art business. Now, with lockdown and loss of supplemental jobs, “I know a lot of people who want to give up their art dreams.”

He brings up an artist he’s known for 20 years who has had to sell off her tools of the trade, abandon her studio and move into her parents’ house. “I am pretty well off compared to other artists,” he says, since his husband Patrick has a decent job with medical benefits.

The student loan is an albatross around Bloom’s neck, however. That was money spent for a double major at a Methodist college, where he was “outed by an on-campus Christian group. I was living in a dorm with these prayer groups around me finding bible passages taped to my door.”

Community within Community

[Sitka Center for Art and Ecology at Cascade Head, Oregon Coast]

The 50th anniversary of Sitka’s founding is 2020, and Alison Dennis laments those events were cancelled because of Covid-19 and the restrictions on gatherings. For Sitka, shifts have taken place in how arts are delivered and framed. Alison and the board applied for CARE and PPP projection. She was able to keep five full-time and 2 part-time workers on staff. “The programs did not allow me to pass money onto the artist. We would have if we could have.”

Artists depend on paid workshops and events where their work is displayed, considered, and sold directly to the public, collectors. She’s quick to emphasize it would be a mistake to create this dichotomy of organizations over artists, or vice versa.

Thanks in part to relief funding, and in part to foundations and private donors, we’re fortunate in that we’ve been able to keep our full staff employed at full pay. Staff capacity is essential to not only respond to this year’s crisis but also to plan for a resilient return. One example is working with instructors to design workshops for next year, such as outdoor painting and sketch booking workshops, with physical distancing in mind, Alison says.

The celebration goes on, since Sitka had its first cabins up and running in 1972, so 2022 seems like an interesting time to promote, celebrate and reposition Sitka for the changing times. Resilience is great, but artists are most of the times soloists, on their own, lone wolves. They can build community, but most of the time that is a cash-poor cooperative group.

I asked Sitka’s Dennis a key question on all our minds: One major shift in this pandemic is the inability to gather, hold openings, do group training, and such? What effects do you see this new normal have had on artists and the relationship to both the general public and students of art?

Sitka’s annual Art Invitational is one example of this dilemma. Each fall we host a regional 3-day art show showcasing over 300 works by over 100 PNW artists, and raising over $40K in direct art sale dollars that go directly into artists’ pockets, she says. This fall’s show was cancelled due to Covid-19. While we’re working to find ways to connect buyers with artists online, neither the experience nor the economic impact is close to the same.

Collecting Dust? He Wants More Lower Economic Folks to Enjoy Original Art!

[Installation of Chuck E. Bloom originals in Snider’s home]

[Installation of Chuck E. Bloom originals in Snider’s home]

The magic power of a poem [of art, of music] consists in it always being filled with duende, in its baptizing all who gaze at it with dark water, since with duende it is easier to love, to understand, and be certain of being loved, and being understood, and this struggle for expression and the communication of that expression in poetry sometimes acquires a fatal character.

— Federico García Lorca, Theory and Play of the Duende, 1933

For 68-year-old Duane Snider, his 39 years as a 9-to-5 blue-collar optical lens grinder left a deep emotional toll on him. He kept from jumping off a bridge (for five years he imagined that act daily where he saw the Ross Island bridge) by galvanizing himself into the world of Portland’s art scene.

We are talking about, he estimates, 3,000 to 4,000 art gallery openings, museum soirées and museum talks and MFA shows.

He says he’s always been the backer of the artist, reluctant about the capitalist bent of art galleries taking sixty percent of the sales of art for their own benefit.

Snider and his wife Linda want to disperse of their large collection (247 pieces and counting) through a model of gifting one piece of art to one deserving, underfunded person at a time.

His collection is chalk-full of Chuck Bloom’s work – over 30 pieces.

I’ve always thought artists are the most brutalized in a capitalist system, Snider tells me. The very richest people are obsessed with controlling artistic culture.

He and I have talked for hours walking the beaches around Waldport. While he is the pied piper for creative people in need, Snider also sees artists as problem solvers. He believes artists need to take control of their work, of their own promotion, and of their sales. “. . . and an increased emphasis on the work as a product.”

The white box model of a gallery exhibit is passe, and many galleries are dropping like flies in this pandemic. Snider harkens back to Portland’s 1960s and ‘70s art scene, citing the Image Gallery, a sort of venue for the people started by Jack McLarty and his wife Barbara.

I believe art is for everyone. And I have always been afraid for artists and believe there will be tremendous casualties for great artists and creative people now with this economic crisis.

Snider recalls the twice-a-week art classes at Portland’s St. Francis church where artists would work with homeless citizens in their artistic expression. Are those days numbered? Maybe.

Bloom, Snider and Molnar believe artists can be that radical thinker and doer, but capitalism takes its own toll on the arts – careerism and milquetoast expression.

But I find today in the U.S., two … or make that three … overriding aspects to public discourse. One is aggression. It is a snarky and sarcastic and hostile populace. Two is white privilege. And you see already that they overlap. Third is a distrust of art and the non-instrumental. This is American masculinity, but it seems to have leaked into much feminist thought as well. In any event the professionalizing of art and cultural production began a long gradual process of excluding radical voices and then even working-class voices. Since theatre is what I know best, and what I do, still, the rise of MFA programs coincided with the removal of disruptive voices. And soon a strange disfigured bureaucratization of culture had taken hold.

– American John Steppling is a playwright, author and commentator: a collection of plays, Sea of Cortez & Other Plays and his book, Aesthetic Resistance and Dis-Interest by Mimesis International. He lives in Norway.

Truth Tellers, Fully Awake, Resistance Fighters

[Daniela Molnar interviewed in LA Times and on local TV]

Daniela Molnar sees a tsunami of shake-ups of smaller art schools since Covid-19 lockdowns exposed more of the inequities of neoliberalism and capitalism. She no longer works for PNCA, which just recently merged with Willamette University.

Her pedigree, at the relatively young age of 41, is impressive: founder of the Art + Ecology program at the Pacific Northwest College of Art, founding co-editor of Leaf Litter, Signal Fire’s art and literary journal, and art editor at Bear Deluxe Magazine.

Interestingly enough, right before the Covid-19 pandemic declaration, Molnar was featured in a February 2020 LA Times article aptly titled – “An Artist Set Out to Paint Climate Change. She Ended Up on a Journey Through Grief.”

She was contemplating the shape produced with missing chunks of the Eliot Glacier on Mount Hood. She was zoning out one day while listening to a lecture by a hydrologist. Then she thought — “I haven’t seen that shape before. Maybe I can use that.”

That process of using crushed rocks mixed with gum arabic, a binder, and water from the rain barrel in her yard, for her, is a process of shaping an “abstract” set of scientific theories like climate change into art. Provoking feelings was her intent, but as she says in the LA Times piece, her own feelings of grief took over.

Given that generalized concept of “grief,” after talking with Daniela, I realize she doesn’t know what the future looks like, yet she still is a proponent of dancing to the beat of her/our own drummer when embodying the life of an artist: “Being an artist is one way to craft an honest life. It’s not going to be an easy life, but artists need to see clearly . . . clarity over ease. Art doesn’t look like any one thing.”

It is necessary for my own sanity to insert a stream of positivity in an article framing this new normal as a time of upheaval, struggles, loss and clouds of unknowing.

If you suddenly and unexpectedly feel joy, don’t hesitate. Give in to it. There are plenty of lives and whole towns destroyed or about to be. We are not wise, and not very often kind. And much can never be redeemed. Still life has some possibility left. Perhaps this is its way of fighting back, that sometimes something happened better than all the riches or power in the world. It could be anything, but very likely you notice it in the instant when love begins. Anyway, that’s often the case. Anyway, whatever it is, don’t be afraid of its plenty. Joy is not made to be a crumb.

– Poet Mary Oliver, Don’t Hesitate, November 4, 2020

Full disclosure: I have never made a living as a poet, novelist, essayist and photographer. For more than 46 years I have cobbled together a living teaching part-time gigs, editing, working in social services case management, undertaking newspaper reporting and more to feed me and my need to write and photograph. This March 2020 my latest book, a short story collection, was derailed as all bookstore readings, conferences, literature confabs, libraries were cancelled.

I critique this new (i.e. old) normal which is illustrated in every group within the political red v. blue spectrum: not questioning authority and their masters, whether it’s Bezos, Trump or Kate Brown; not questioning draconian lockdown rules; accepting Zoom schools; failing to see heads on pikes after the massive graft in the trillions of dollars for US corporations; and no collective action for the hundreds of millions losing livelihoods. That’s bad enough; however, while leftist artists are both validated by the enormity of the neoliberal course of US predatory and parasitic capitalism displayed ever-more clearly in 2020, we are more ostracized economically and pushed way outside the margins of the “other” than any other time in history.

I’ll end with Hiroyuki Hamada, a New York artist and writer:

I am sure that with all sorts of manmade substances tossed into the environment, we probably do have physical components that can’t be attributed to our psychological needs alone, but still, I have a serious doubt about how our society deems creative behaviors as sickness because they don’t coincide with the system requiring obedient people for efficiency, productivity and profits. The unquantifiable creative potential smashed by such a tendency can be enormous.

And speaking of the urgent need for radical imagination and keeping one’s hate pure, I think the lack of those is not only stifling our capability to come up with the solutions, but it is blinding many of us from simply seeing the mechanism itself.

“Shelter Within The Storm: A Dialog On Politics And Culture” with Phil Rockstroh.

For more on Daniela’s work, her web site.

For more on Chuck’s work, his web site.

For more on the Sitka Center for Art and Ecology, their web site.

The post The Collector, Non-profit, Painter and Teacher first appeared on Dissident Voice.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.