From left to right: Vijay Prashad, Fred M’membe, Diego Sequera, and Erika Farías in Caracas, 2019. Photograph taken by Yeimi Salinas.

On 12 August 2021, the people of Zambia will vote to elect a new president, who will be the seventh person elected to the office since Zambia won its independence from the United Kingdom in 1964 if the incumbent loses. The incumbent, President Edgar Lungu, is facing a strong challenge from Fred M’membe, the presidential candidate of the Socialist Party Zambia.

M’membe knows the importance of a challenge. As the editor of The Post since its creation in 1991, M’membe has long faced malicious harassment and political persecution. The voice of M’membe’s The Post sizzled with truth-telling; silenced in 2016, it was reborn as The Mast.

In 2009, an editorial in The Post described how, despite decades of independence, Zambia remained in the claws of an unjust world system. ‘Economically speaking, Zambia is the tip of the tail of the global dog,’ wrote The Post. ‘When the dog is happy, we find ourselves merrily flicking from side to side; when the dog is miserable, we find ourselves coiled up in a dark and smelly place’. No wonder that every government from Frederick Chiluba (1991-2002) to sitting President Edgar Lungu has tried to muzzle the paper and its editor, who cast a spotlight on the awful surrender of the Zambian political elite to multinational corporations and foreign bondholders. Now the editor of The Post is a presidential candidate.

Mapopa Manda (Zambia), Visionary, 2019.

Fred M’membe is a humble man who demurs about his presidential run through a warm smile. ‘Ours is a collective leadership’, he tells me of the Socialist Party, which was launched in March 2018. The manifesto of the Party pledges to reverse Zambia’s slide into privatisation and de-industrialisation, social processes that have damaged social life in the country and created a sense of despondency amongst the masses. A reading of that manifesto in these COVID-19 times is chilling: ‘Due to the poor state of water and sanitation, urban areas are prone to water-borne diseases that break out almost every year’, with water scarce and half the population without connection to sanitation systems.

The neoliberal policies pushed since the end of the government of Zambia’s first president, Kenneth Kaunda (1964-1991), have been catastrophic for Zambians. These policies, M’membe told me, ‘are creating an enormous time bomb in our country. We shouldn’t resign ourselves to hunger, unemployment, squalor, disease, ignorance, hopelessness, and despair. Struggling for a better Zambia means, in part, to build a better Zambia’.

Lutanda Mwamba (Zambia), Chuma Grocery, 1993.

Zambia is a rich country with a poor population. Zambia’s poverty rate is estimated between 40% and 60% (the country only has statistics up to 2015). A World Bank household survey conducted in early June 2020 found that half of the families who relied on agriculture saw a substantial loss of income and 82% of families that earned income from non-farm businesses saw their livelihoods shrink. The World Bank found that remittance flows into Zambia also precipitously declined.

Because of the drop in income, households reduced their consumption of goods, especially food. In 2019, before the pandemic, the Global Hunger Index found the hunger situation in Zambia to be ‘alarming’. But there is no reliable data on the growth of hunger caused by the pandemic, which prevented the Index from properly assessing the situation. Instead, it assessed the situation as ‘serious’. ‘Zambia’, M’membe told me, ‘stands at the brink of a major catastrophe’.

In November 2020, Zambia defaulted on a $42.5 million payment towards a Eurobond. President Lungu’s government has been talking to the IMF ever since, hoping to get a bailout without stringent austerity measures. Such austerity measures – including cuts in public services that the country can ill afford during the pandemic – would jeopardise Lungu’s chances in the August 2021 elections. In early March, the IMF’s staff visit concluded that ‘significant progress’ has been made toward an ‘appropriate policy package’, but no details or timetable have been released.

Mulenga Chafilwa (Zambia), Drip Drip Drip, 2014.

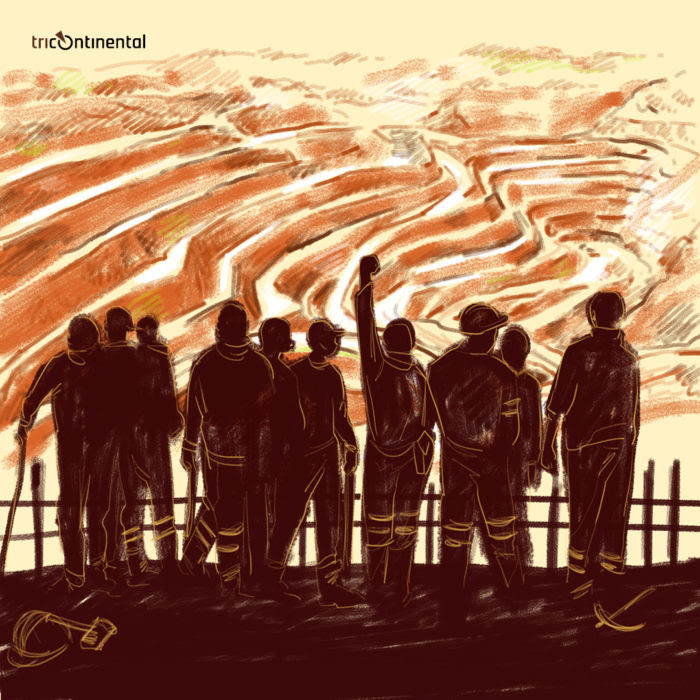

A month before the IMF team met with Zambian officials, the country’s minister of mines Richard Musukwa announced that the country’s copper production had reached 882,061 tonnes. This was an increase by 10.8% from 2019 figures, a ‘historical high’ according to Musukwa. Given the move to electric cars and to more high-tech appliances, copper wiring is certain to be in high demand, which is why Zambia hopes to produce more than 1 million tonnes a year in the next few years. Copper prices are inching upwards ($4 per pound) toward the highs of 2011 ($4.54 per pound). There is plenty of money to be made from copper, particularly for the Zambian people.

Four companies dominate Zambian copper: Barrick Lumwana of Canada’s Barrick Gold, FQM Kansanshi of Canada’s First Quantum, Mopani of Switzerland’s Glencore, and Konkola Copper Mines of the UK’s Vedanta. These are major mining companies that leech Zambia of its resources through creative means such as transfer mispricing and bribery. In 2019, Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research spoke to Gyekye Tanoh, head of the Political Economy Unit at the Third World Network-Africa based in Accra (Ghana), about the situation of ‘resource sovereignty’. His comments on Zambia merit re-reading:

Because Zambia is now utterly reliant on copper exports, the international copper price movements have a preponderant and distorting effect on the exchange rate of the Kwacha [Zambia’s currency]. This distortion and the limited revenue from copper exports impacts the competitiveness and viability of other, non-copper exports as a result of the fluctuations of the Kwacha. The fluctuations also impact the social sector. A study done in 2018 showed that changes in the exchange rates oscillated between -11.1% to +13.4% in the period between 1997 and 2008. The loss of funds from donors to the Ministry of Health in Zambia amounted to US $13.4 million or $1.1 million per year. Because of the collapse of the Kwacha between 2015 and 2016, per capita health expenditure in Zambia fell from $44 (2015) to $23 (2016).

M’membe told me that poverty levels in the Copperbelt Province, the heart of Zambia’s wealth, are very high. It is striking that 60% of the children in this copper-rich area cannot read. ‘Foreign multinational corporations have been the major beneficiaries’, he explained. A cozy relationship with the Zambian elites enables these firms to pay low taxes and take their profits out of the country, as well as to use techniques such as outsourcing and subcontracting to skirt Zambia’s labour laws. This industry, M’membe said, ‘still operates along colonial lines’. Indeed, in Phyllis Deane’s Colonial Social Accounting (1953), she shows that in Northern Rhodesia – Zambia’s name during colonial rule – two-thirds of the profits were taken out of the territory to pay foreign shareholders, while two-thirds of the remainder went to the European workers and the minuscule leftovers went to the vast majority, the African miners.

‘Reliance on non-renewable resources like minerals for growth is, by definition, unsustainable’, M’membe reflected. Any government in Zambia will have to rely on copper – only a third of it mined to date – until the country’s economy and society are properly diversified. The Socialist Party has proposed a range of policies to harness the copper resources, from cutting better deals with the current owners to full-scale nationalisation (a policy that is currently being imposed on Zambia, as First Quantum and Glencore have cut back on their investments, forcing the government to step in). M’membe laid out seven points for a just mining policy for the immediate period:

- The socialist government will declare minerals as strategic metals and provide a protective legal environment for their extraction. The export of concentrates will be outlawed, and the marketing of minerals will be coordinated by the state.

- Zambian labour will have their power strengthened by laws and by political will.

- Mining firms will have to source at least 30% of their industrial inputs from Zambia, which would encourage manufacturing.

- Zambia Consolidated Copper Mines Limited-Investment Holdings (ZCCM-IH), a state-owned corporation, will take a controlling interest in all new mines.

- Resource rent or variable income tax will be introduced to secure additional mineral rents.

- All proceeds from mineral sales will first be credited in Bank of Zambia accounts – an essential aspect of currency and balance of payments management and stability.

- Mines will have to adhere to state-of-the-art environmental technologies, practices, and standards.

Beyond this, the socialist government will encourage the creation of miners’ cooperatives, particularly for manganese, which is cheaper to mine.

Mwamba Mulangala (Zambia), Political Strategies, 2009.

There is seriousness of purpose in the Socialist Party’s agenda for Zambia. M’membe travels the length and breadth of his country speaking about this agenda. ‘We should win because of what we believe in’, he tells me. He believes that every child in Zambia should be able to read and should be able to go to sleep without hunger pangs. This is a belief that should be shared by every human being.

This article was posted on Thursday, April 8th, 2021 at 8:12pm and is filed under Austerity, Mining, Socialism, Zambia.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.