Noticing the way journalists seemed unable to resist commenting on our work, even if it was just to slag us off, Glenn Greenwald tweeted us in 2012:

‘You are really deeper in the heads of the British establishment-serving commentariat than anyone else – congrats.’

If that was true then, our relationship with the commentariat now feels more like a case of out of sight, out of mind. We have been blocked en masse on Twitter, even by loveable liberals like Jeremy Bowen, Jon Snow, Mark Steel (yes, ‘radical’ Mark Steel!), Steve Bell, Frankie Boyle (the less said about that the better) and, of course, Owen Jones and George Monbiot.

Where polite questions once provoked lengthy, thoughtful replies from the likes of Richard Sambrook, director of BBC news, and Guardian reader’s editor, Ian Mayes, they’re now met with sullen silence. As Noam Chomsky commented to us:

‘Am really impressed with what you are doing, though it’s like trying to move a ten-ton truck with a toothpick. They’re not going to allow themselves to be exposed.’

It makes sense, does it not, that the ‘ten-ton truck’ would be better off ignoring the ‘toothpick’? What does the truck stand to gain from engaging when it can simply thunder on its way? Why risk picking up a tiny reputational scratch?

A journalist friend – one of our ‘mainstream’ sleepers, programmed to rise on our command – wrote to us:

‘You must see the reaction in a newsroom when one mentions Chomsky or Pilger. They run the other way, and I can see they are afraid by the look on their faces. Fact is that once you understand and admit what you are doing, you can’t continue with it. When I mentioned Chomsky, one person commented, “Oh, he’s way out there.” “Way out where?” I asked.’

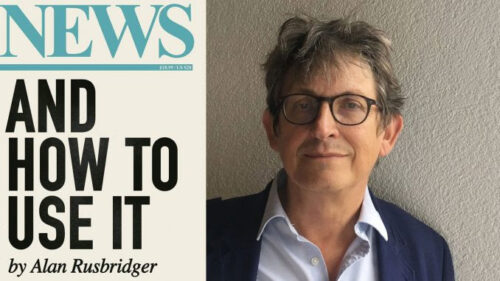

Imagine our surprise, then, to discover that in his latest book, News and How to Use It, the Guardian’s long-term former editor (1995-2014), Alan Rusbridger, mentions Media Lens repeatedly, including lengthy quotes, a link to a media alert, and even a level of agreement. This is surprising, not least because Rusbridger blocked us on Twitter many years ago and has not replied to our emails since about 2005. We assumed he had forgotten all about us.

But there is more: Rusbridger discusses Edward Herman and Noam Chomsky’s ‘propaganda model of media control’ with its five ‘filters’, in detail, filter by filter. He declares the book that presented the model, Manufacturing Consent, a ‘classic’.

Anyone checking UK national media databases for mentions of the ‘propaganda model’ will find a handful of mentions, mostly in passing. (John Naughton erroneously noted of Rusbridger in his Guardian review: ‘Uniquely among established journalists, he takes seriously the work of Noam Chomsky and Edward Herman on “manufacturing consent”…’ Naughton, professor of the public understanding of technology at the Open University, would be surprised at just how many of the better journalists have told us privately that they agree with much, or all, of the propaganda model.)

Rusbridger also discusses the work of John Pilger and Robert Fisk at length. Even media activist terms like ‘MSM’ (‘“mainstream” media’), ‘lamestream media’ (a Trumpism) and ‘presstitutes’ are discussed.

To put this in perspective, the Guardian’s token leftist, Owen Jones – absurdly described by Russell Brand as, ‘our generation’s Orwell’ – made no mention of Herman, Chomsky, Pilger, Fisk, the propaganda model, or Media Lens, in his two most recent books, The Establishment (2014) and This Land! (2020).

‘Out, Damned Spot! Out, I Say!…’

A recurring, haunting presence in News and How to Use It, the propaganda model appears to play Banquo’s ghost to Rusbridger’s Macbeth. As our media insider warned, ‘once you understand and admit what you are doing, you can’t continue with it’.

Rusbridger has continued with it, but is clearly struggling to reconcile his sense of himself as a benevolent, principled liberal with the propaganda model’s damning assessment of the role someone in his position has to play.

The same internal conflicts were apparent in a remarkable interview conducted by one of us, David Edwards (DE), with Rusbridger (AR) in 2000. In the interview, as in his book, Rusbridger began by agreeing with the central thesis of the propaganda model:

DE: ‘Basically, one radical analysis of the media is that the pressures of advertising, of wealthy owners and parent companies, have an effect similar to filtering, so that facts and ideas that are damaging to powerful advertisers and powerful parent companies, and so on, tend to be filtered from press reporting.’

(7 second pause)

AR: ‘Um, I’m sure there is a… (6 second pause) that the pressures of ownership on newspapers is, is pretty important, and it works in all kinds of subtle ways – I suppose “filter” is as good a word as any. The whole thing works by a kind of osmosis. If you ask anybody who works in newspapers, they will quite rightly say, “Rupert Murdoch”, or whoever, “never tells me what to write”, which is beside the point: they don’t have to be told what to write.’

DE: ‘That’s right, it’s just understood.’

AR: ‘It’s understood. I think that does work, and obviously the general interests of most of the people who own newspapers are going to be fairly conventional, pro-business interests. So, you know, I’m sure that is broadly true, yes.’

What is so interesting is that Rusbridger not only agreed with the propaganda model, he agreed that the model explains why the model is ignored by corporate media:

AR: ‘It doesn’t get written about a lot in the mainstream press, but I mean, you know, for obvious reasons. But there’s a lot of it in books… I agree, but you can sort of understand the reasons why, why it doesn’t happen.’

But then came the rub:

DE: ‘So it’s not able to be discussed?’

(8-9 second pause)

AR: ‘Um…’

Rusbridger hesitated before the looming Shakespearean spectre of his own cognitive dissonance. As Chomsky has observed, the role of a liberal editor is to draw a line: ‘to say, in effect, this far and no further’. How far would Rusbridger go? Because he, of course, knew what was coming next:

DE: ‘I mean, could you discuss it [in the Guardian] if you wanted to?’

AR: ‘Oh yes. I would say it’s something we do fairly regularly. But then we’re not owned by a… We’re owned by a trust; we haven’t got a proprietor. So we’re in a sort of unique position of being able to discuss this kind of stuff.’

As if any undergraduate, any secondary school pupil, could fail to understand that the lack of a proprietor did not mean the elite, (then) Scott Trust-run, profit-maximising, ad-dependent, state source-dependent, corporate Guardian was ‘in a sort of unique position of being able to discuss this kind of stuff’.

This was so disconcerting in the interview because the articulate, intelligent, friendly, reasonable, comparatively humble, and, in fact, likeable, Guardian editor had revealed himself to be an example of what psychologist Erich Fromm called a ‘marketing orientation’.

The marketing character experiences him or herself ‘as a commodity, or rather simultaneously as the seller and the commodity to be sold’ (p. 70). He puts his job, his career, his corporation first. His view of the world is drastically shaped and limited by his need to sell himself and his product on the market.

A marketing character like Rusbridger is reasonable and rational, but only up to a point. The problem, as we will see, is that the suffering of hundreds of thousands, indeed millions, of human beings begins where that point ends.

The limits are not set by a lack of intelligence – it wasn’t that Rusbridger couldn’t understand why the propaganda model also applies to the Guardian – but by the logic of the job description, of the market and profit. Anything that seriously threatens these linked personal-corporate priorities is rejected, ignored, brushed under the psychological carpet. Nietzsche wrote:

‘Memory says, “I did that.” Pride replies, “I could not have done that.” Eventually, memory yields.’

Memory yields everywhere in ‘News and How to Use It’, as Rusbridger’s marketing character screens the truth from awareness. His talent in this regard is such that we suspect he would find much that follows genuinely surprising.

Mass Death And Problematic Haircuts – Prickly Pilger

Consider his section on John Pilger. Rusbridger has to recognise Pilger’s achievements; to do otherwise would be absurdly biased, particularly given that he hosted his column in the Guardian for many years (a column Pilger described as a ‘fig leaf’).

Pilger, he says, ‘embodies many of the classic qualities of the very best of investigative journalists: he is brave, uncompromising and tenacious’. (p. 200)

That sounds positive enough, but alarm bells should already be ringing. Firstly, all three adjectives can be interpreted negatively – one can be idiotically ‘brave, uncompromising and tenacious’. And indeed, Rusbridger’s first, thinly-veiled slur points in this direction:

‘He also appears utterly secure in the armour of his self-belief.’ (p. 200)

As we have often noted, the first resort of every corporate journalist in attacking any dissident is to focus on their supposed ‘narcissism’. Charles Jennings didn’t use the word, but he had exactly this in mind when he commented in 1999:

‘I guess you have to have John Pilger. With his tan, his Byronic haircut, his trudging priestly delivery and his evident self-love, your main instinct is to flip right over to BBC1…’

Pilger is ‘brave, uncompromising and tenacious’, but many journalists share these qualities, which do not at all describe Pilger’s significance, or why Rusbridger is discussing his work at such length.

Pilger’s ‘classic qualities’ relate to the fact that, surrounded by corporate compromisers and actual state stooges, he reports honestly on the crimes of state-corporate power – including ‘liberal’ power, including corporate media power. Pilger tells the unfiltered, uncompromised truth about the foundations of power. His focus is on speaking up for the victims of power, not on serving power.

A serious analysis of the merits of Pilger’s work, then, simply has to include an honest appraisal of his deepest criticisms of power – these are what make Pilger so unusual and important. But, of course, that is something marketing character Rusbridger cannot do, just as he could not honestly discuss the relevance of the propaganda model for the Guardian in his 2000 interview. Instead, he focuses time and again on Pilger’s supposed character flaws.

Alas, says Rusbridger, ‘even some of his greatest fans have found him an increasingly difficult, prickly figure shooting first and not always asking questions later’. (p. 200.)

Or as Roy Greenslade wrote of Pilger 16 years ago:

‘He is undoubtedly a prickly character. As an editor once remarked, only a little unfairly, he is a hero until you know him.’

In similar vein, Rusbridger cites a former Question Time editor, ‘a self-confessed fan’, who had come to the view that Pilger was ‘someone I’d rather stick needles in my eyes than be stuck in a lift with’. (p. 200)

By the way, yes, Pilger is prickly – he is a passionate, feeling individual – but that is part of his sincerity and honesty. In our experience, he is also an extraordinarily generous and compassionate person. His sincerity, of course, makes it difficult for him to be in the company of ethical eels like Greenslade and BBC Question Time editors. As Harold Pinter once wrote:

‘Dear Tom

Thanks for your invitation to host a fundraising dinner in the private room of a top London restaurant.

I would rather die.

All the best,

Yours,

Harold’

But quite regardless of their accuracy, these ad hominem attacks on Pilger are, in fact, a rejection of honest debate.

Consider that, in reviewing Pilger’s 2000 documentary, Paying the Price: Killing the Children of Iraq, which focused on the UN’s assertion that US-UK sanctions had been responsible for the deaths of 500,000 children under five in Iraq, Joe Joseph wrote in The Times:

‘In his latest, harrowing documentary… the fearless Australian journalist reminds us that – however daunting the odds stacked against him – he is not going to shy away from his lifelong commitment to make TV programmes with extremely long titles…’

Joseph added:

‘His angry, I-want-some-answers-please documentary style, like his haircut, is a hangover from the 1970s; and like much of the Seventies, he is enjoying a small retro revival. Pilger is the Prada of TV journalism.’

One has to pinch oneself to remember that this was a review of a documentary exploring highly credible claims that Britain and the US were responsible for the deaths of half a million small children.

If the point is not clear, imagine if someone with serious, verifiable evidence interrupted a town hall meeting to warn that government troops were at that moment burning hundreds of children alive in the local school. Now, we might urgently seek to challenge and check the claims, but what would we make of someone who responded by mocking the haircut of the person raising the alarm? Would we not find this a morally depraved response?

Likewise, Rusbridger would certainly be justified in discussing the evidence for and against Pilger’s most damning criticisms of power, but to focus repeatedly on his ‘prickly’ personality is again morally depraved, because it is part of marketing character Rusbridger’s unwillingness to engage with the genuinely life-and-death issues Pilger is discussing. Children really are being burned to death and Pilger is one of the few journalists trying to draw attention to their plight.

In other words, Rusbridger perceives his focus on Pilger’s personality as ‘balance’, but actually it is his way of avoiding, not just balance, but a rational debate about what Pilger’s journalism is really all about.

After all, who gives a damn about personal prickliness when, in 1996, at a time when liberals at the Guardian and elsewhere were united in swooning at his feet, Pilger was all but alone in writing of Tony Blair:

‘To all but the trusting or cynical it must be dawning that the next Labour government is quite likely to be more reactionary, nastier and a greater threat to true democracy than its venal Tory predecessor.’

At the time, this was universally dismissed as wretched, ‘old-left’ carping. A few months later, a Guardian leader under Rusbridger’s editorship responded thus to Blair’s ascent to power:

‘“Few now sang England Arise, but England had risen all the same.”’

Tragicomically, the Guardian predicted that, by 2007, Blair’s triumph would be seen as ‘one of the great turning-points of British political history… the moment when Britain at last gave itself the chance to construct a modern liberal socialist order’.

Pilger was right, Rusbridger et al were disastrously wrong. Blair went on to kill one million people in Iraq, transforming the Labour Party into a Tory-Lite façade that eliminated British democratic choice for a generation. The state-corporate propaganda blitz that recently consumed Jeremy Corbyn had its roots in Blair’s great coup, in frantic efforts to maintain the anti-democratic status quo he installed.

In 2005, Pilger said of Blair and Iraq:

‘By voting for Blair, you will walk over the corpses of at least 100,000 people, most of them innocent women and children and the elderly, slaughtered by rapacious forces sent by Blair and Bush, unprovoked and in defiance of international law, to a defenceless country.’ (Pilger, ‘

A Rusbridger Guardian leader commented:

‘While 2005 will be remembered as Tony Blair’s Iraq election, May 5 is not a referendum on that one decision, however fateful… We believe that Mr Blair should be re-elected to lead Labour into a third term this week.’

Pilger was right, the Guardian’s position was a moral obscenity. No Official Enemy leader responsible for mass death on such a scale would ever be forgiven and normalised in this way.

In June 2008, Pilger wrote of Obama:

‘Like all serious presidential candidates, past and present, Obama is a hawk and an expansionist. He comes from an unbroken Democratic tradition, as the war-making of presidents Truman, Kennedy, Johnson, Carter and Clinton demonstrates.’

A Guardian leader under Rusbridger commented:

‘They did it. They really did it. So often crudely caricatured by others, the American people yesterday stood in the eye of history and made an emphatic choice for change for themselves and the world…

‘Today is for celebration, for happiness and for reflected human glory. Savour those words: President Barack Obama, America’s hope and, in no small way, ours too.’

Again, Pilger was right – Obama went on to bomb seven Muslim-majority countries. He oversaw the devastation of Syria and Yemen, and the near-complete destruction of Libya.

In his book, Rusbridger mentions the word ‘Libya’ exactly once, in passing, referring to what he foolishly calls ‘the Libyan revolution’ (p. 182. Showing a similar level of insight, Rusbridger describes Trump’s April 2018 blitz of Syria after the alleged chemical weapons attack in Douma as ‘retaliatory’, p.108). He makes no mention at all of the Libyan war, or of the Guardian’s relentless propagandising for war under his editorship that, just eight years after the Iraq calamity, was again based on completely fake pretexts.

Once again, Pilger was a lone voice defying corporate media herdthink:

‘The Nato attack on Libya, with the UN Security Council assigned to mandate a bogus “no fly zone” to “protect civilians”, is strikingly similar to the final destruction of Yugoslavia in 1999. There was no UN cover for the bombing of Serbia and the “rescue” of Kosovo, yet the propaganda echoes today. Like Slobodan Milosevic, Muammar Gaddafi is a “new Hitler”, plotting “genocide” against his people. There is no evidence of this, as there was no genocide in Kosovo.’

A Guardian leader under Rusbridger saw things differently:

‘But it can now reasonably be said that in narrow military terms it worked, and that politically there was some retrospective justification for its advocates as the crowds poured into the streets of Tripoli to welcome the rebel convoys earlier this week.’

Again, Pilger was entirely vindicated, not least by a 9 September 2016 report into the war from the foreign affairs committee of the House of Commons. The issue Rusbridger ignores is no small matter – in relentlessly promoting a devastating, illegal war, he and his staff were complicit in a major war crime.

Pilger ‘has become the doyen of a certain style of uncompromising journalism’, Rusbridger continues. He means ‘controversial’:

‘His roiling anger is palpable and grows with each passing year, using language that has certainly “slipped the leash”.’ (p. 201)

‘For instance’, says Rusbridger, quoting Pilger:

‘Should the CIA stooge Guaido and his white supremacists grab power, it will be the 68th overthrow of a sovereign government by the United States, most of them democracies. A fire sale of Venezuela’s utilities and mineral wealth will surely follow, along with the theft of the country’s oil, as outlined by John Bolton.’

Perhaps because he’s an avid Guardian reader, Rusbridger appears to find this outrageous. In 2019, former Guardian journalist Jonathan Cook tweeted:

‘Oh look! Juan Guaido, the figurehead for the CIA’s illegal regime-change operation intended to grab Venezuela’s oil (as John Bolton has publicly conceded), is again presented breathlessly by the Guardian as the country’s saviour’

It was indeed a consistent and shameful Guardian trend. Cook linked to a Guardian piece titled: ‘“¡Sí se puede!” shouts rapturous crowd at Juan Guaidó rally’.

Writing on the Grayzone website, Dan Cohen and Max Blumenthal supplied some perspective:

‘Juan Guaidó is the product of a decade-long project overseen by Washington’s elite regime change trainers. While posing as a champion of democracy, he has spent years at the forefront of a violent campaign of destabilization.’

We could go on adding examples of how ‘prickly’, unsavoury lift companion, Pilger – with his ‘roiling anger’ and ‘Lear-like ranting’ at ‘too high a volume with no tone or balance control’ (p. 204) – was right in expressing forbidden truths that Rusbridger cannot discuss because it would mean exposing himself and the Guardian in exactly the way the ‘ten-ton truck’ would never do.

In 2006, Pilger wrote:

‘In reclaiming the honour of our craft, not to mention the truth, we journalists at least need to understand the historic task to which we are assigned – that is, to report the rest of humanity in terms of its usefulness, or otherwise, to “us”, and to soften up the public for rapacious attacks on countries that are no threat to us.’

This is not something Rusbridger could ever honestly discuss. Why? Because it’s exactly the role he performed as editor of the Guardian.

There is much more we could say about the book – on Rusbridger’s similarly blinkered comments on Robert Fisk and Julian Assange. Rusbridger does deserve credit for discussing the propaganda model and he even cites examples in support of our arguments on the filtering effect of advertising (pp. 47-9). He accepts that ‘many aspects of journalism go oddly unexamined’ (p. 11) but cannot perceive the structural propaganda function of an industry that reflexively supports illegal wars on countries like Serbia, Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, Syria and Yemen.

The most striking example of ‘mainstream’ propaganda function in recent times has been the fascistic, cross-spectrum campaign to destroy Corbyn. In essence, the entire corporate media system declared Corbyn off-limits to voters, disallowed. Rusbridger’s own newspaper led this extraordinary campaign of demonisation and yet he mentions Corbyn just once, listing his inability to recognise TV presenters Ant and Dec as an example of trivial news, or ‘chaff’ (p. 46).

As Herman and Chomsky, and indeed Fromm, would expect, marketing character Rusbridger is blind to the significance of a mild socialist threat to corporate power being smeared into oblivion by an entire corporate media system, that ‘rough old trade’. (p. 225)

This article was posted on Monday, December 7th, 2020 at 6:42pm and is filed under Book Review, Media, Media Bias, UK Media.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.