In the same document, Steven Alexander, head of contaminants at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, also urged TVA to “consider radionuclide analyses of the dredged material as well as existing sediments that may be removed during the dredging process.” TVA told Alexander that their first of three phases of dredging wouldn’t disturb legacy contaminants. But they acknowledged that the second phase, which involved digging deeper into the riverbed closer to the Clinch, might. TVA said they’d focus on “minimizing disturbance of legacy sediment.”

Dredging this sediment, mixing it in with the recovered coal ash, and categorizing the concoction of Kingston’s coal ash and old nuclear waste as “newly-generated hazardous waste” could have been catastrophic for TVA — the nuclear sediments would have touched almost every part of the cleanup operation.

Consider the legacy waste in the riverbed as a handful of sand. After it leaves the river, the ultra-fine material encounters Kingston’s long assembly line: First, it’s dredged by operators like Thacker. Then long pipes shoot it from the river into a series of canals and holding ponds, further mixing it in with the coal ash. Massive machines like dump trucks and trackhoes disperse it onto a plateau that TVA called the Ball Field. There, the tiny particles dry in pancake-like piles across the plain. On particularly windy days, they spin into dust devils with the ash, covering the sky like curtains 100 feet in the air. Once it’s dry enough, the combined coal ash and nuclear material is scooped onto a rail line for shipment to a solid waste landfill 350 miles south in Uniontown, Alabama.

A house sits adjacent to the cleanup zone of the Kingston coal ash spill. Shawn Poynter

Between the Emory and this landfill, hundreds of workers handled the ash. Fugitive dust escaped to nearby communities across two states. Nearly 40,000 train cars eventually dumped the ash in Uniontown, a low-income, 90-percent-Black community near Selma. Prior to the first shipment in June 2009, the ash was tested for radionuclides to make sure it fell below Alabama’s threshold for radium. Samples showed radium levels up to two times the Alabama Department of Public Health’s limit. But the company that owned the landfill argued it should be exempt from the limit, because its own evaluation determined that workers were safe at exposure levels over eight times Alabama’s limits. The state’s public health department granted its request, doubling the threshold for radium exposure.

That same summer, all workers hired at Kingston were required to take a 40-hour training in Hazardous Waste Operations and Emergency Response, or HAZWOPER, approved by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, or OSHA. Though coal ash is not a federally regulated hazardous waste, the training was required because materials within the ash (like arsenic, cadmium, chromium, copper, lead, mercury, nickel, selenium, and zinc) are individually regulated as hazardous. Most workers took the training in a nearby laundromat or at a local school. Brad Green, a foreman at the Kingston site, testified in the 2018 trial that it was hard to stay awake during the training because workers thought the information about hazardous waste did not pertain to them. “It wasn’t nothing about coal fly ash,” he said. None of the workers who spoke to me heard anything from their supervisors, or those conducting the training, about possible exposure to hazardous waste at Kingston, and they were not given the baseline or follow-up physicals that are legally required at official hazardous waste sites.

Within four years, workers were sharing stories of plummeting testosterone levels, a symptom that multiple studies have linked to radiation exposure like that experienced by male cancer survivors who have undergone chemotherapy. Men in their 30s and early 40s started taking testosterone injections. Brewer, the truck driver, had his levels plummet by 75 percent. Now, at 46 years old, he takes a shot for his testosterone every other week. Thacker, the dredge operator, was told by his doctor that he had the testosterone levels of a man twice his age. When he reported this symptom to Jacobs, however, Thacker says he was laughed out of their offices.

A response crew at the TVA Fossil Plant in Kingston, Tennessee, works on issues related to the coal ash spill. Shawn Poynter

A response crew at the TVA Fossil Plant in Kingston, Tennessee, works on issues related to the coal ash spill. Shawn Poynter

Dismissal of worker health concerns by TVA is well-documented in recent years. In June 2013, another truck driver named Joe Pursiful submitted an official complaint claiming that a supervisor mocked men on site complaining about low testosterone. “It’s a joke,” the supervisor told Pursiful. “I’ll take up their slack.” (Pursiful died earlier this month, at the age of 61.) In an anonymous complaint to TVA’s Office of Inspector General the following month, another worker claimed that he and others were experiencing bronchial infections, sinus infections, and low testosterone. Nobody took their symptoms seriously. A different supervisor said “the workers were making up the health issues to avoid being laid off,” according to the text of the complaint.

Meanwhile, OSHA did little to ensure its training was implemented. Two months after the spill, OSHA received an anonymous complaint that employees were working in hazardous conditions due to TVA’s negligence. But the agency chose not to act. “OSHA has decided not to conduct an inspection in response to this report,” an agency official wrote to TVA. “However, since the allegations of the violation of standards have been made, you should investigate the alleged violations.” Even as TVA was responsible for investigating itself, the utility was paying Jacobs $12,500 for every month that zero OSHA violations were identified at the site. (According to the Jacobs spokesperson, there were no OSHA violations during the time the contractor was on site.)

A spokesperson for the Department of Labor, the cabinet agency that oversees OSHA, did not respond to Grist and the Daily Yonder’s inquiry about the complaint in question but suggested that standard procedures were followed. “OSHA investigates all safety and health violation allegations within the agency’s jurisdiction,” the spokesperson wrote.

TVA was forced to institute HAZWOPER training in the summer of 2009 because of a new EPA order that governed the site. The order, which stemmed from the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, Respondent, and Liability Act, or CERCLA, entered Kingston into the nation’s Superfund program. Enrolling in Superfund, which typically monitors hazardous waste sites like old chemical plants and defunct nuclear stations, turned out to be both a blessing and a curse for TVA. On the plus side, CERCLA granted TVA access to a pot of federal cleanup money. On the other, it made the consequences of discovering hazardous material above certain thresholds even more severe.

If hazardous materials were found co-mingling with the coal ash, Superfund law could trigger a change in how the site was managed, officially recategorizing Kingston as a hazardous waste site. The entire cleanup operation would fall under more stringent, more expensive, and more time-consuming guidelines. Cleanup workers, for example, would be required to wear respirators and limit their exposure time. TVA could be vulnerable to new legal claims in both Tennessee and Alabama for initially treating the waste as though it were non-hazardous. (An EPA spokesperson declined to answer specific questions, but he confirmed that the agency approved all cleanup procedures and claimed that TVA was the “lead federal agency” implementing the order.)

Understanding the EPA order requires jumping down a legal rabbit hole. In 1976, Congress passed the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act, or RCRA, which separated household and industrial waste into two separate categories: hazardous and non-hazardous. The mining industry, fearful that increased regulation of its waste materials would run up costs, lobbied Congress for a loophole. Four years later, lawmakers approved an amendment that essentially excluded mining waste from being deemed hazardous, even though much mining activity involves materials considered hazardous under RCRA law. Coal ash, in particular, contains dozens of constituents the EPA considers hazardous.

While the EPA does not list coal ash or coal-fired power plants as a typical source of radiation or radioactive waste, the ash can contain elements emitting radioactivity at 10 times their naturally occurring levels. These higher levels are due to unstable atoms undergoing radioactive decay; their frequencies can be dangerous for people who touch, ingest, or are simply near them. But lobbying from the coal industry has kept more than 3 billion tons of coal ash over 1,400 U.S. sites largely exempt from federal regulation. (In 2015, the Obama administration tried to force the closure of unlined coal ash ponds with new regulation, but the Trump administration weakened the rule this year, installing a loophole that could extend the lives of the ponds.)

“All energy utilities are having a problem admitting that they’ve been using material for the last 50 years that should be kept away from the environment, and weak regulations allow them to do that,” said Avner Vengosh, a professor of geochemistry and water quality at Duke University. “For them, saying it’s hazardous material is the last thing they would do.”

An office space at the TVA Fossil Plant looks out at the Kingston coal-fired facility. Shawn Poynter

An office space at the TVA Fossil Plant looks out at the Kingston coal-fired facility. Shawn Poynter

Discovering legacy contamination — hazardous waste not subject to the loophole for coal ash — might have required TVA to do just that. The EPA’s Dee Stewart had warned TVA about the “potential implications” of nuclear legacy waste mixing in with their “non-hazardous” waste. According to TVA’s responses to Stewart’s comments, the utility teamed up with the DOE to analyze sediment samples from the Emory and Clinch Rivers for legacy contaminants. A TVA report published in early 2011 states that ash sampling showed cesium-137 within the Emory, but not in the ash taken out of the river. This discovery led to the work stoppage on the final section of the Emory, but it’s unclear if it had any other effect on the way the broader cleanup operation was conducted.

Additional internal documents obtained by Grist and the Daily Yonder demonstrate that TVA was aware that worker exposure to cesium-137, or other forms of legacy contamination, could be a financial and legal nightmare. In July 2009, two months after the CERCLA order, TVA officials gave a confidential internal presentation in which they said that one of the most severe risks to their bottom line would be stopping or altering the cleanup plan they’d already put into place.

In an affidavit from the 2018 trial, a foreman indicated that this fear had been internalized by workers on the ground. According to the affidavit, a Jacobs safety manager, with the support of TVA supervisors, ordered his workers to remove personal protective equipment and destroy common dust masks. (At the onset of the cleanup, many workers had supplied their own safety gear or acquired it from Kingston’s utility room.) The supervisor allegedly stated “that the site was a CERCLA site and that if they wore dust masks or respiratory protection, it would change the status of the site.” A heavy equipment operator recalled at trial that this same safety manager once told him: “If these people knowed what was in this ash, they’d quit.”

In response to allegations that appropriate personal protective equipment was not provided and even discouraged due to the site’s regulatory status, the Jacobs spokesperson told Grist that “the site’s designation as a CERCLA site was not and could not have been based on the use of respiratory protection.” She added that, although plaintiffs alleged they were denied dust masks during the 2018 trial, “we are not aware of any instance in which respiratory protection was denied to a worker who requested it and met the applicable criteria” under the site’s official safety plan.

According to court records, however, early versions of this plan did not list all the constituents in coal ash, including radioactive material. Only four employees ever managed to obtain Jacobs’ approval to secure and use dust masks, though records indicate that dozens asked. Court records also confirm that dust masks were destroyed on site by Jacobs supervisors. No one at the spill site ever received a respirator.

During TVA’s 2009 presentation in the wake of the CERCLA order, the utility worried that the number of health problems could rise if levels of radiation and heavy metals in the coal ash “are deemed to be higher than first reported.” Such radiation levels could lead to another risk: class action lawsuits.

According to recently reported documentation that dates back to the year after the spill, radiation levels were, in fact, much higher than first reported.

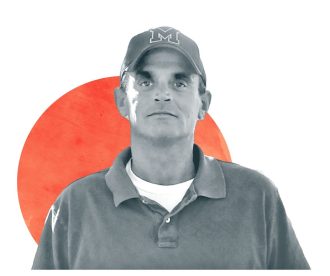

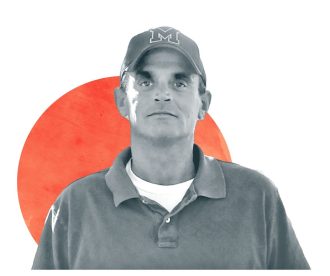

Dan Nichols Grist / Courtesy of Dan Nichols

Dan Nichols Grist / Courtesy of Dan Nichols

In 2017, a former chemist named Dan Nichols stumbled upon a news story that revealed the existence of the additional health problems TVA feared. High levels of uranium had been measured in the urine of a former cleanup worker named Craig Wilkinson. Like Thacker, Wilkinson had worked the night shift. After dredges piped the coal ash back onshore, Wilkinson used heavy equipment to scoop, flip, and dry the wet ash along the Ball Field.

Although Wilkinson worked at the Kingston site for less than a year, he quickly developed health issues, including chronic sinus infections and breathing problems that eventually led to a double-lung transplant. Frustrated by his sudden decline in health, Wilkinson shelled out over $1,000 for a toxicology test because he wanted to know what occupational hazards might be lingering in his body.

After reading Wilkinson’s story, Nichols sat stunned. Though he was not associated with the spill, he’d been unable to shake his obsession with the Kingston disaster. Nichols had worked as a Memphis-based field chemist for a wastewater technology company, and he was used to studying lab reports on industrial water supplies and samples. For years he’d been trying to solve a mystery that no one else seemed to be aware of: why Kingston regulators deleted and then altered a state-sanctioned report showing extremely high levels of radiation at the cleanup site.

Roughly a month after the spill, Nichols read a Duke University press release stating that ash samples collected at Kingston by a team led by Vengosh, the geochemist, showed radium levels well above those typically found in coal ash. Nichols knew that the state environmental regulator, the Tennessee Department for Environment and Conservation, or TDEC, was also testing soil and ash samples at the site. After seeing Vengosh’s high radium readings, he wondered if TDEC’s report would also show high levels of either radium or uranium. (Radium is a decay element of uranium.) Later that spring, Nichols visited TDEC’s website and discovered the test results.

“I opened it up and went to uranium, and it was just off the charts,” Nichols recalled. In a 2020 affidavit, Nichols reported that these levels were “extremely high so as to be alarming.” At least 27 soil and ash samples were collected from at least 20 different sites surrounding Kingston beginning January 6, 2009. The levels ranged from 84 parts per million (ppm) to 2,000 ppm. The average level was over 500 ppm, as much as 50 times the typical uranium content found in coal ash.

The next morning, when Nichols slumped back into his computer chair and refreshed TDEC’s website, he saw that the report had been changed. The high uranium readings had plummeted. Now the average uranium levels in the ash were 2.88 ppm, a tenth of the typical uranium content found in coal ash and illogically, below levels naturally occurring in soil. Luckily, Nichols had downloaded the unaltered report the night before.

A month later, Nichols sent the two lab reports to one of the attorneys representing Tennessee residents affected by the spill in a lawsuit they’d brought against TVA. According to Nichols, the lawyers weren’t interested. Nevertheless, Nichols was determined to find more proof of the unusually high levels of on-site radiation. In between cutting hay and spraying weeds on his family farm, he spent years poring over information online about TVA, coal ash, and uranium before he stumbled across Wilkinson’s story.

A broken dike at the Kingston Fossil Plant released an estimated 1.1 billion gallons of coal ash into its surroundings. Shawn Poynter

A broken dike at the Kingston Fossil Plant released an estimated 1.1 billion gallons of coal ash into its surroundings. Shawn Poynter

Back in 2014, Wilkinson’s urine tested for unusually high levels of both mercury and uranium. The mercury is more easily explained: The most common cause of mercury contamination, according to the EPA, is coal-fired power plant emissions, which account for 44 percent of all man-made mercury pollution. The 2008 spill released 29 times the mercury reported at the Kingston site for the entire decade before it, and TVA documents show high levels of additional legacy mercury were present in the Clinch River and could have migrated into the Emory. Today, Wilkinson has symptoms attributable to methylmercury poisoning including blurry vision, fatigue, a hearing impairment, memory loss, and loss of coordination that caused him to fall out of the machines he operated until retiring on disability in 2015.

But most shocking to Nichols was the high level of uranium in Wilkinson’s body — it was 10times the U.S. average, and identical to the median levels that one study found in workers exposed to the substance. Prolonged occupational exposure to uranium is strongly linked to chronic kidney disease, which Wilkinson suffers from. Because Wilkinson’s toxicology results were taken four years after he left Kingston, they likely show lower uranium levels than what he and other cleanup workers initially had.

Wilkinson’s results left no doubt in Nichols’ mind that the original uranium readings he’d saved were significant. A reporter for the Knoxville News-Sentinel, Jamie Satterfield, contacted him after the report he saved showed up in court proceedings. Satterfield published a story about the altered uranium readings in May of this year.

In response to her story, TDEC told the News-Sentinel that its updated uranium readings, which plummeted by 98 percent, were due to a change in the sampling method used for the tests. (Satterfield also reported that radium levels had been lowered between the initial TDEC report Nichols downloaded and the updated one; the department attributed this to a “data entry error.”) In an email response to Grist and the Daily Yonder, a TDEC spokesperson elaborated that the sampling lab, which was neither staffed nor supervised by TDEC, “discovered there were interferences in the analysis of soil and ash samples for uranium” and subsequently changed the method of analysis from one EPA-approved protocol to another. The new results were then published without public notice of the alteration.

“Changing lab reports is a very serious thing,” Nichols said. “But I can assure you data entry errors don’t cause a man to test for unusually high levels of uranium. That’s [TDEC’s] big problem.”

Unbeknownst to Nichols, Russell Johnson, the district attorney with jurisdiction over Roane County, where Kingston is located, had informed TDEC’s commissioner in 2017 that he was beginning a criminal probe into the Kingston cleanup. “I am deeply concerned with the apparent intentional conduct of the cleanup contractors and their supervisors, actions that took place in Roane County, conduct that may indeed have caused serious bodily injury or possibly even death to a number of people,” Johnson wrote in a letter to TDEC.

In concert with the Tennessee Bureau of Investigation, Johnson began investigating whether TVA or its contractors “suppressed information” as part of the coverup alleged in the 2013 worker lawsuit against Jacobs. They now have Nichols’ evidence as well. But despite this ongoing investigation, it’s unclear if workers will ever learn for certain whether or not they were exposed to dangerous substances besides the coal ash itself. (Bob Edwards, an assistant district attorney working under Johnson, told Grist and the Daily Yonder that the district attorney’s office could not comment on a pending investigation.)

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

September 2003 marked two watershed moments in my life: I started high school, and I was introduced to Ryan Atwood, Seth Cohen, Marissa Cooper, and Summer Roberts, the cast of the unforgettable teen soap

September 2003 marked two watershed moments in my life: I started high school, and I was introduced to Ryan Atwood, Seth Cohen, Marissa Cooper, and Summer Roberts, the cast of the unforgettable teen soap