The approval of COVID-19 vaccines has raised hopes that the “new normal” of a post-pandemic world will start to emerge in 2021.

But international rights groups say civil society must be able to return to its “normal” pre-pandemic role to prevent a permanent expansion of overreaching government power.

They argue that civil society must provide checks and balances to ensure the rollback of temporary, emergency public-health measures imposed — and sometimes misused — during 2020.

Transparency International has long warned about “worrying signs that the pandemic will leave in its wake increased authoritarianism and weakened rule of law.”

“The COVID-19 crisis has offered corrupt and authoritarian leaders a dangerous combination of public distraction and reduced oversight,” the global anti-corruption group says.

“Corruption thrives when democratic institutions such as a free press and an independent judiciary are undermined; when citizens’ right to protest, join associations, or engage in initiatives to monitor government spending is limited,” Transparency International says.

Protesters clash with police in front of Serbia’s National Assembly building in Belgrade on July 8 during a demonstration against a weekend curfew announced to combat a resurgence of COVID-19 infections.

says authoritarianism in theory, as well as authoritarian regimes in practice, were “already gaining ground” before the pandemic.

Hamid says some aspects of the post-pandemic era — such as COVID-19 tracing schemes and increased surveillance — can create “authoritarian temptations” for those in charge of governments.

“During — and after — the pandemic, governments are likely to use long, protracted crises to undermine domestic opposition and curtail civil liberties,” Hamid concludes in a Brookings report called Reopening The World.

The intent to suppress on the part of the government can provoke an unusually intense desire to expose its mistakes on the part of the press, the legislative branch, and civil society.”

But despite those dangers, Hamid remains cautiously optimistic about political freedoms recovering in a post-pandemic world.

In due time, he says, the removal of emergency restrictions will help “political parties, protesters, and grassroots movements to communicate their platforms and grievances to larger audiences.”

“Democratic governments may try to suppress information and spin or downplay crises as well — as the Trump administration did — but they rarely get away with it,” Hamid concludes.

“If anything, the intent to suppress on the part of the government can provoke an unusually intense desire to expose its mistakes on the part of the press, the legislative branch, and civil society,” he says.

In countries from Russia to Turkmenistan, authoritarian tendencies under the guise of pandemic control have included the use of emergency health measures to crack down on political opposition figures and to limit the freedom of the press.

They also have included attempts by authorities to restrict the ability of civic organizations to scrutinize and constrain the expansion of executive power.

Crackdown In Baku

Actions taken by Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev’s government are a case in point.

In March, Baku imposed tough new punishments for those convicted of “violating anti-epidemic, sanitary-hygienic, or lockdown” rules.

The new criminal law imposed a fine of about $3,000 and up to three years in prison for violations such as failing to wear a mask in public.

Those convicted of spreading the virus face up to five years in prison.

A police officer inspects a woman’s documents under the gaze of an Azerbaijani soldier in Baku in July during the coronavirus pandemic. Azerbaijan deployed troops to help police ensure a tight coronavirus lockdown in the capital and several major cities.

Human Rights Watch (HRW) warned that Baku’s criminal punishments for spreading COVID are “not a legitimate or proportionate response to the threat posed by the virus.”

The U.S.-based rights group says it is all too easy for such laws to be misused to “target marginalized populations, minorities, or dissidents.”

During the summer — amid public dissatisfaction about the lack of a resolution to the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict with neighboring Armenia — Aliyev also faced dissent over rampant corruption, economic mismanagement, and his handling of the pandemic.

Aliyev’s response was to launch a crackdown in July widely seen as an attempt to eliminate his political rivals and pro-democracy advocates once and for all.

A Washington Post editorial said Aliyev had “blown a gasket” with a “tantrum” that threatened to “obliterate what remains of independent political forces in Azerbaijan.”

More than 120 opposition figures and supporters were rounded up in July by Aliyev’s security forces — mostly from the opposition Azerbaijan Popular Front Party (AXFP).

Two opposition figures among those arrested were charged with violating Azerbaijan’s emergency COVID measures — Mehdi Ibrahimov, the son of AXFP Deputy Chairman Mammad Ibrahim, and AXFP member Mahammad Imanli.

HRW says its own review of pretrial court documents concluded that Imanli was “falsely accused” of spreading COVID-19 and endangering lives by not wearing a mask in public.

Ibrahimov’s arrest was based on a claim by police that he took part in an unauthorized street demonstration while infected with the coronavirus.

But Ibrahimov’s lawyer says COVID tests taken after his arrest in July show he was not infected.

In fact, he said, the charges of violating public-health rules were only filed against Ibrahimov after he was detained and authorities discovered he was the son of a prominent opposition leader.

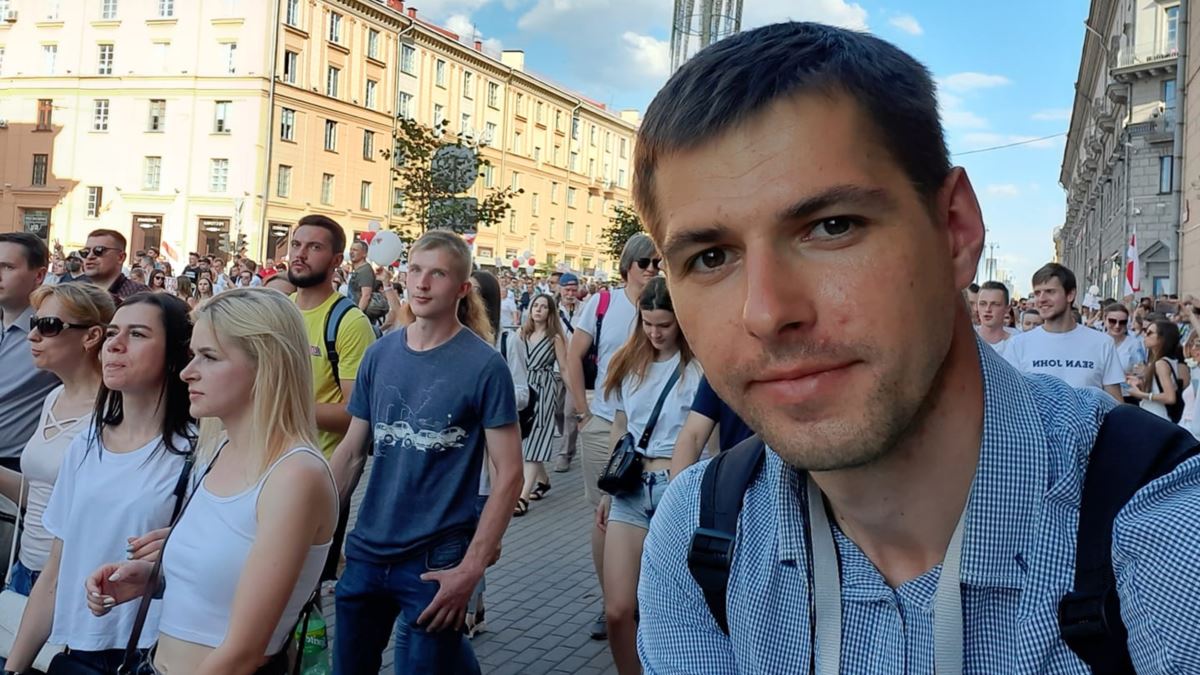

Belarusian Borders

Critics accuse Belarus’s authoritarian ruler, Alyaksandr Lukashenka, of using COVID-19 restrictions to suppress mass demonstrations against his regime.

To be sure, the use of politically related COVID-19 measures is seen as just one tool in Minsk’s broader strategy of intensified police crackdowns.

The rights group Vyasna said in December that more than 900 politically motivated criminal cases were opened in 2020 against Belarusian opposition candidates and their teams, activists, and protesters.

The ongoing, daily demonstrations pose the biggest threat to Lukashenka’s 26-year grasp on power — fueled by allegations of electoral fraud after he was declared the landslide winner of a sixth term in a highly disputed August 9 presidential election.

While Minsk downplayed the threat posed by COVID-19 for months, Lukashenka has repeatedly accused the opposition and hundreds of thousands of protesters on the streets of being foreign-backed puppets.

A Belarusian border guard wears a face mask and gloves to protect herself from the coronavirus early in the pandemic. Belarus closed off its borders to foreigners on November 1.

On November 1, after months of brutal police crackdowns failed to halt the anti-government demonstrations, Belarus closed off its borders to foreigners.

The State Border Committee said the restrictions were necessary to “prevent the spread of infection caused by COVID-19.”

In December, authorities expanded the border ban to prevent Belarusians and permanent residents from leaving the country — ostensibly because of the pandemic.

Lukashenka’s own behavior on COVID-19 bolstered allegations the border closures are a politically motivated attempt to restrain the domestic opposition.

In late November, Lukashenka completely disregarded safety protocols during a visit to a COVID-19 hospital ward — wearing neither gloves nor a mask when he shook hands with a medic in full protective gear.

Opposition leader Svyatlana Tsikhanouskaya, who left Belarus under pressure after she tried to file a formal complaint about the official election tally, says the border restrictions show Lukashenka is “in a panic.”

Russia’s Surveillance State

In Moscow, experts say the pandemic has tested the limitations of Russia’s surveillance state.

Russia’s State Duma in late March approved legislation allowing Prime Minister Mikhail Mishustin to declare a state of emergency across the country and establish mandatory public health rules.

It also approved a penalty of up to five years in prison for those who “knowingly” disseminate false information during “natural and man-made emergencies.”

The legislation called for those breaking COVID-19 measures to be imprisoned for up to seven years.

In April, President Vladimir Putin tasked local governments with the responsibility of adopting COVID-19 restrictions.

Experts say that turned some Russian regions into testing grounds for how much increased surveillance and control Russians will stand for.

It also protected the Kremlin from political backlash over concerns that expanded government powers to control COVID-19 could become permanent in post-pandemic Russia.

Meanwhile, Moscow took steps to control the free flow of information about Russia’s response to the pandemic.

“It is staggering that the Russian authorities appear to fear criticism more than the deadly COVID-19 pandemic,” Amnesty International’s Russia director, Natalia Zviagina, said.

“They justify the arrest and detention of Anastasia Vasilyeva on the pretext that she and her fellow medics violated travel restrictions,” Zviagina said. “In fact, they were attempting to deliver vital protective equipment to medics at a local hospital.”

Anastasia Vasilyeva, a Russian doctor who heads a medical workers union, was arrested in April after she exposed shortcomings in the health system’s preparations to fight COVID-19.

Zviagina concludes that by putting Vasilyeva in jail, Russian authorities exposed “their true motive.”

“They are willing to punish health professionals who dare contradict the official Russian narrative and expose flaws in the public health system,” she said.

The State Duma also launched reviews and crackdowns in 2020 on reporting by foreign media organizations — including RFE/RL — about the way Russia has handled COVID.

Human Rights Watch said police “falsely claimed” protesters violated COVID-19 measures — “yet kept most of the detained protesters in overcrowded, poorly ventilated police vehicles.”

In July, police in Moscow detained dozens of journalists during a protest against Russia’s growing restrictions on media and freedom of expression.

In several cases, Human Rights Watch said police “falsely claimed” protesters violated COVID-19 public health measures — “yet kept most of the detained protesters in overcrowded, poorly ventilated police vehicles where they could not practice social distancing.”

HRW Russia researcher Damelya Aitkozhina says those cases “have taken the repression to a new level.”

Aitkhozhina says authorities in Moscow “detained peaceful protesters under the abusive and restrictive rules on public assembly and under the guise of protecting public health, while exposing them to risk of infection in custody.”

Rights activists say local authorities in some Russian regions also used COVID-19 measures as an excuse to crack down on protesters.

In late April, authorities in North Ossetia detained dozens of demonstrators from a crowd of about 2,000 people who’d gathered in Vladikavkaz to demand the resignation of regional leader Vyacheslav Bitarov.

Thirteen were charged with defying Russia’s COVID-19 measures and spreading “fake information” about the pandemic.

In Russia’s Far East city of Khabarovsk, authorities used COVID-19 measures to try to discourage mass protests against the arrest of a popular regional governor on decades-old charges of complicity in murder.

Demonstrators say the charges were fabricated by the governor’s local political opponents with help from the Kremlin.

While municipal authorities in Khabarovsk warned about the risks of COVID-19 at the protests, police taped off gathering places for the demonstrations — claiming the move was necessary for COVID-19 disinfection.

But the crowds gathered anyway — reflecting discontent with Putin’s rule and public anger at what residents say is disrespect from Moscow about their choice for a governor.

Demo Restrictions In Kazakhstan

Kazakh President Qasym-Zhomart Toqaev signed legislation in late May that tightened government control over the right of citizens to gather for protests.

Going into effect during the first wave of the global COVID-19 outbreak, the new law defines how many people can attend a demonstration and where protests can take place.

Critics say the new restrictions and bureaucratic hurdles include the need for “permission” from authorities before protests can legally take place in Kazakhstan — with officials being given many reasons to refuse permission.

RFE/RL also has reported on how authorities in Kazakhstan used the coronavirus as an excuse to clamp down on civil rights activists who criticized the new public protest law.

Kazakh and international human rights activists say the legislation contradicts international standards and contains numerous obstacles to free assembly.

Information Control In Uzbekistan

Uzbek President Shavkat Mirziyoev has been praised by international rights groups since he came to power in late 2016 for his slight easing of authoritarian restrictions imposed by his predecessor, the late Islam Karimov.

But the COVID-19 crisis has spawned a battle between emerging independent media outlets and the state body that oversees the press in Uzbekistan — the Agency for Information and Mass Communications (AIMC).

Officials in Tashkent initially claimed Uzbekistan was doing well in combating COVID-19. But by the summer, some media outlets were questioning that government narrative.

They began to delve deeply into details about the spread of the pandemic and its human costs within the country.

AIMC Director Asadjon Khodjaev in late November threatened “serious legal consequences” about such reporting — raising concerns that COVID-19 could be pushing Uzbekistan back toward more authoritarian press controls, much like the conditions that existed under Karimov.

Kyrgyz Upheaval

Before the pandemic, Kyrgyzstan was considered by the Paris-based Reporters Without Borders as Central Asia’s most open country for the media. But Kyrgyzstan’s relative openness has been eroded by lockdowns and curfews imposed since a state of emergency was declared on March 22.

Most independent media outlets have had difficulty getting accreditation or permits allowing their journalists to move freely in Bishkek or other areas restricted under the public health emergency.

Violent political protests erupted after Kyrgyzstan’s controversial parliamentary elections on October 4 — which were carried out despite the complications posed by the COVID-19 control measures.

The political tensions led to the downfall of President Sooronbai Jeenbekov’s government, plans to hold new elections, and the declaration of a state of emergency in Bishkek that included a ban on public demonstrations.

Pascaline della Faille, an analyst for the Credendo group of European credit insurance companies, concludes that social tensions contributing to the political upheaval were heightened by the pandemic.

She says those tensions included complaints about the country’s poor health system, an economy hit hard by COVID-19 containment measures, and a sharp drop in remittances from Kyrgyz citizens who work abroad.

Turkmenistan Is Ridiculed

One of the world’s most tightly controlled authoritarian states, Turkmenistan has never had a good record on press freedom or transparency.

Not surprisingly, then, President Gurbanguly Berdymukhammedov’s claim that he has prevented a single COVID-19 infection from happening in his country has been the target of global ridicule rather than admiration.

Turkmen President Gurbanguly Berdymukhammedov

Ashgabat’s continued insistence that the coronavirus does not exist in Turkmenistan is seen as a sign of Berdymukhammedov’s authoritarian dominance rather than any credible public health policies.

In early August, the World Health Organization (WHO) announced that Berdymukhammedov had agreed to give WHO experts access to try to verify his claim about the absence of COVID-19 in his country.

Hans Kluge, WHO’s regional director for Europe and Central Asia, said Berdymukhammedov had “agreed” for a WHO team “to sample independently COVID-19 tests in country” and take them to WHO reference laboratories in other countries.

But after more than four months, Berdymukhammedov has still not kept his promise.

Meanwhile, Turkmenistan’s state television broadcasts perpetuate Berdymukhammedov’s cult of personality by showing him opening new “state-of the-art” medical facilities in Ashgabat and other big cities.

Privately, Turkmen citizens tell RFE/RL that they don’t believe the hype.

They say they avoid hospitals when they become ill because facilities are too expensive for impoverished ordinary citizens and state facilities often have little to offer them.

Patients at several regional hospitals in Turkmenistan told RFE/RL they’ve had to provide their own food, medicine, and even firewood to heat their hospital rooms.

Still, in a former Soviet republic known for brutal crackdowns on critics and dissent, nobody openly criticizes Turkmenistan’s health officials about the dire situation in hospitals out of fear of reprisals.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.